COVID-19 Science Update released: July 21, 2020 Edition 32

The COVID-19 Science Update summarizes new and emerging scientific data for public health professionals to meet the challenges of this fast-moving pandemic. Weekly, staff from the CDC COVID-19 Response and the CDC Library systematically review literature in the WHO COVID-19 databaseexternal icon, and select publications and preprints for public health priority topics in the CDC Science Agenda for COVID-19 and CDC COVID-19 Response Health Equity Strategy.

Here you can find all previous COVID-19 Science Updates.

PEER-REVIEWED

The COVID-19 vaccine-development multiverseexternal icon. Heaton. NEJM (July 14, 2020)

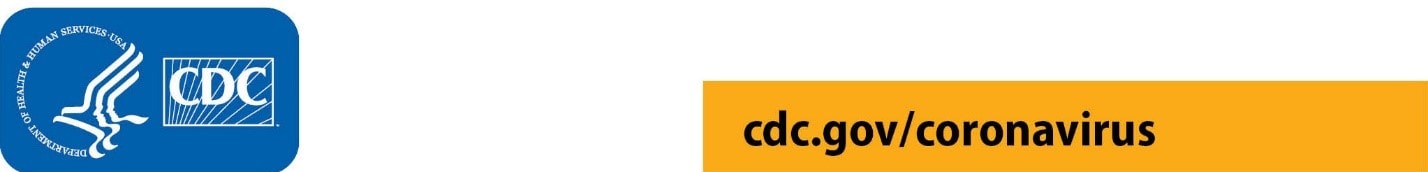

A vaccine to prevent COVID-19 is urgently needed. In this editorial, Dr. Penny Heaton describes the 3 to 9 year vaccine development pathway to reach phase 1 safety trials (Figure), and how now in the 6 months from the time SARS-CoV-2 sequences were first identified, Jackson et al. have reported preliminary results from the phase 1 trial of an mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Safety and immunogenicity findings from this study are promising; further research will be needed to demonstrate efficacy and long-term safety.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Heaton. Timeline for traditional vaccine development; from discovery to a phase 1 safety trial typically takes 3-9 years, as indicated in red. From NEJM. Heaton. The COVID-19 vaccine-development multiverse. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe2025111. Copyright ©2020 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 — Preliminary reportexternal icon. Jackson et al. NEJM (July 14, 2020).

Key findings:

- All 45 participants receiving the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine developed neutralizing antibody activity against SARS-CoV-2.

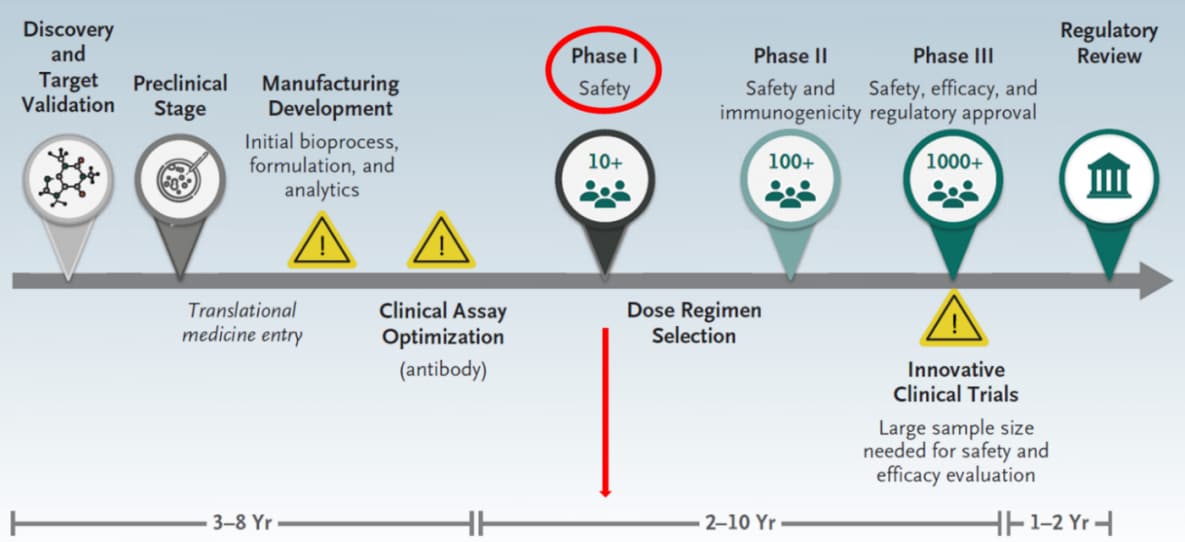

- Antibody responses were higher with higher dose; titers were higher with the second vaccination (Figure).

- Adverse events (fatigue, chills, headache, myalgia, and pain at the injection site) were more common after the second vaccination, particularly with the highest dose.

- No trial-limiting safety concerns were identified.

Methods: A phase 1, open-label trial of a candidate vaccine mRNA-1273 (targets SARS-CoV-2 spike protein) among 45 healthy adults, 18-55 years who received 2 vaccinations 28 days apart in 3 doses (25 μg, 100 μg, or 250 μg) with 15 participants in each dose group. Limitations: No information on efficacy, antibody response duration, and long-term safety.

Implications: Findings support advancement of the mRNA-1273 vaccine to later-stage clinical trials.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Jackson et al. Geometric mean and interquartile range of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) IgG titers to the vaccine by study day within each dose group. For each dose group, titers increased with increasing study day. From NEJM. Jackson et al. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. Copyright ©2020 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Reports have described Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) after SARS-CoV-2 infection; however, Kawasaki disease (KD)-like illness is even rarer in adults. The following case studies describe KD-like illness reported in two adults.

PEER-REVIEWED

COVID-19 associated Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory disease in an adultexternal icon. Sokolovsky et al. American Journal of Emergency Medicine (June 25, 2020).

Key findings:

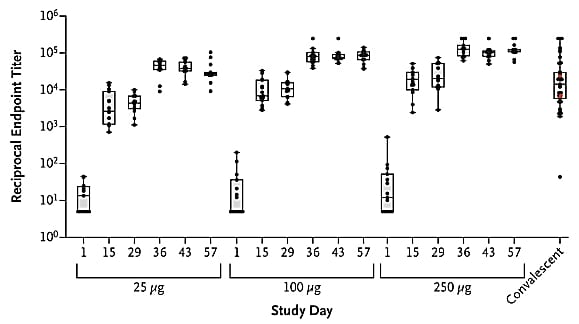

- KD-like illness was diagnosed in an adult with serologic evidence of a previous COVID-19 infection.

- Key features included nonexudative conjunctivitis with heliotrope (purple) rash, mucositis with cracked lips, extremity edema, palmar erythema, and diffuse maculopapular rash (Figure).

Methods: A case study on a previously healthy 36 year-old Hispanic female with SARS-CoV-2 infection presented with KD-like illness. Limitations: Single case report.

Figure:

Note: From Sokolovsky et al. Features of the case including nonexudative conjunctivitis with heliotrope rash (1A), mucositis with cracked lips (1B), extremity edema (1C, 1D), palmar erythema (1D), and diffuse maculopapular rash (1E). This article was published in American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Sokolovsky et al., COVID-19 associated Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory disease in an adult, Copyright Elsevier 2020. This article is currently available at the Elsevier COVID-19 resource center: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-centerexternal icon.

An adult with Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19external icon. Shaigany et al. Lancet (July 10, 2020).

Key findings:

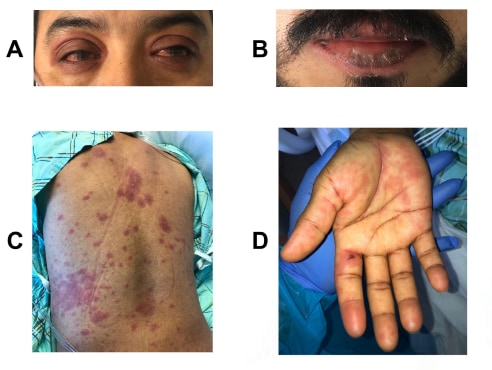

- Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome was diagnosed in an adult with COVID-19.

- Features included non-exudative conjunctivitis, periorbital edema with overlying erythema, lip cheilitis (i.e., red, cracked, swollen), and erythema on back, and palms (Figure).

Methods: A case study of a previously healthy Hispanic male aged 45 years with SARS-CoV-2 infection and Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Limitations: Atypical features of multisystem inflammatory syndrome presented; single case.

Figure:

Note: From Shaigany et al. Clinical features including non-exudative conjunctivitis, periorbital edema with overlying erythema (A), lip cheilitis (B), and erythema on back (C), and palms (D). This article was published in Lancet, Vol 396, Shaigany et al., An adult with Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19, Page e8-e10, Copyright Elsevier 2020. This article is currently available at the Elsevier COVID-19 resource center: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-centerexternal icon.

Implications of both studies (Sokolovsky et al. & Shaigany et al.): Similarly, to MIS-C being identified in children, clinicians and public health officials need to be vigilant about COVID-19-associated cases of Kawasaki-like illness in adults. Robust studies are needed to understand the extent of Kawasaki-like illness in adults.

PEER-REVIEWED

Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19external icon. Carfi et al. JAMA (July 9, 2020).

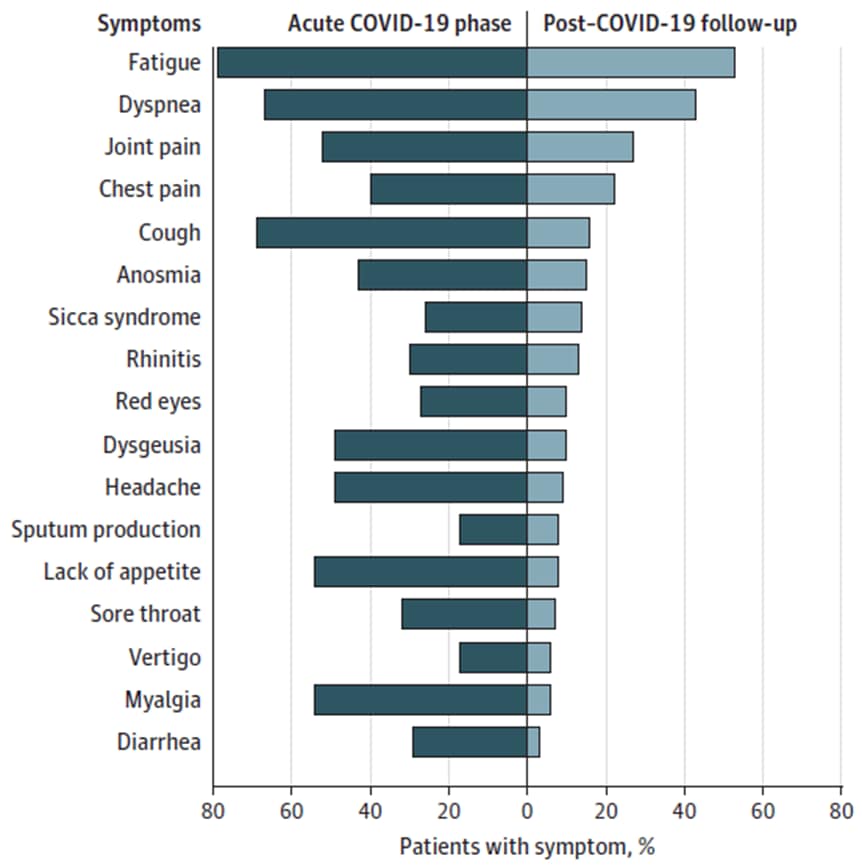

Key findings:

- Among the 143 recovered COVID-19 patients, 87% still had symptoms an average of 60 days after hospital discharge.

- 44% reported worsened quality of life.

- Most common lingering symptoms: fatigue (53%), shortness of breath (43%), and joint pain (27%) (Figure).

Methods: Assessment of 143 hospital discharged patients recovering from COVID-19, between April 21 and May 29, 2020, Rome, Italy. Limitations: No information on pre-coronavirus symptoms or symptom severity.

Implications: Continued monitoring of recovered COVID-19 patients for long-term effects may be needed.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Carfi et al. Percentages of patients presenting with specific COVID-19–related symptoms during acute illness (left, dark teal) and at the time of the follow-up visit (right, light teal). Reproduced with permission from JAMA. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603. Copyright©2020 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Incidence of stress cardiomyopathy during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemicexternal icon. Jabri et al. JAMA Network Open. (July 9, 2020).

Key findings:

- Among the 1,914 COVID-19-negative patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), there was a significant increase in the incidence of stress cardiomyopathy during the COVID-19 period (Figure).

- The incidence of stress cardiomyopathy was 7.8% during the COVID-19 period compared with 1.5%-1.8% during the pre-pandemic period (Figure).

- The rate ratio comparing the COVID-19 pandemic period with the pre-pandemic period was 4.58 (95% CI 4.11-5.11; p <0.001).

- Patients with stress cardiomyopathy during the COVID-19 pandemic had a longer median hospital length of stay compared with those hospitalized in the pre-pandemic period.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study of incidence of stress cardiomyopathy patients presenting between March and April 2020 compared with 4 control groups with ACS during the pre-pandemic period. Stress cardiomyopathy was diagnosed in accordance with the international Takotsubo syndrome diagnostic criteria. Limitations: Not generalizable.

Implications: With an increase incidence of stress cardiomyopathy during the COVID-19 pandemic, public health interventions may be needed to address associated psychological, social, and economic stress.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Jabri et al. Incidence of stress cardiomyopathy per 100 ACS presentations during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (March-April 2020) and pre-pandemic periods. Licensed under CC-BY.

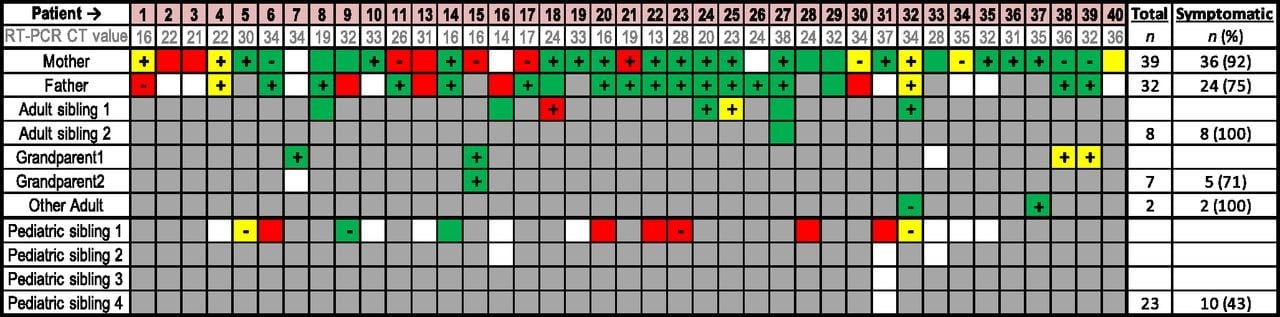

COVID-19 in children and the dynamics of infection in familiesexternal icon. Posfay-Barbe et al. Pediatrics (July 10, 2020).

Key findings:

- Most children had mild or atypical presentation.

- Common comorbidities included: asthma (10%), diabetes (8%), obesity (5%), premature birth (5%), and hypertension (3%).

- Seven children (18%) needed hospitalization; none needed ICU admission; all resolved symptoms by 7 days after diagnosis.

- Among the 111 household contacts (HHCs), 85% of adult and 43% of pediatric siblings developed symptoms (Figure).

Methods: Retrospective chart review and HHC tracing of 40 children <16 years tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Limitations: Not representative of all pediatric SARS-CoV-2 cases; recall bias from HHCs; potential under-reporting of symptoms.

Implications: Extensive household contact tracing is possible and can inform the dynamics of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Similarly, to other studies, the results highlight that children are less likely to be main sources of infection in familial clusters.

Figure:

Note: From Posfay-Barbe et al. HHCs with asymptomatic, suspected, and confirmed SARS-CoV-2. Symptomatic HHCs who developed symptoms before, simultaneously to, and after study patients. The white cells represent asymptomatic HHCs. The grey cells represent absence of family member inside household cluster. “+” and “−” = SARS-CoV-2 NP RT-PCR results; patients without testing have an empty square. Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics. 146 (2) e20201576. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1576. Copyright © 2020 by the AAP.

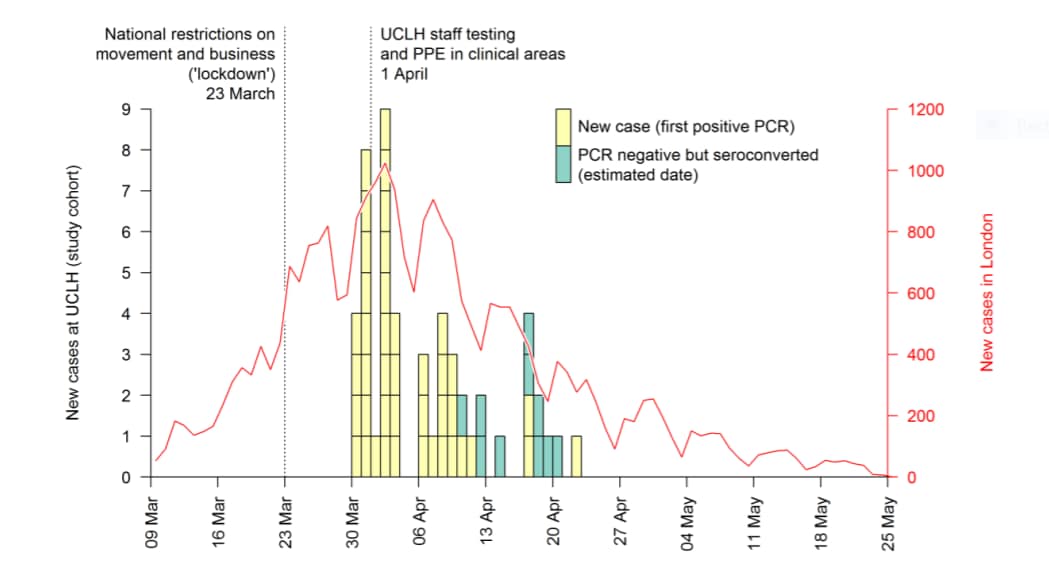

Pandemic peak SARS-CoV-2 infection and seroconversion rates in London frontline health-care workersexternal icon. Houlihan et al. Lancet (July 9, 2020).

Key findings:

- 44% (87/200) of healthcare workers (HCWs) had evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection at any timepoint, detected either by serology or RT-PCR.

- 42 (21%) HCWs tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR in at least one swab, of which 38% did not report any symptoms. There were 10 HCWs that seroconverted (Figure).

- Among 33 HCWs who tested positive by serology but tested negative by RT-PCR, 32 remained negative by RT-PCR during one-month follow-up but one tested positive by RT-PCR on days 8 and 13 after enrollment.

Methods: A prospective cohort study among 200 high-risk HCWs in a London hospital between March 26 and April 8, 2020. NP swabs for RT-PCR were collected twice per week with symptom data, and blood samples monthly for serology testing. All HCWs used PPE during patient interactions. Limitations: Single hospital with short duration of follow up.

Implications: HCWs caring for COVID-19 patients are at high risk of infection and should be prioritized for PPE and vaccines when they become available. Those entering the study with detectable anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies but not detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA – findings consistent with recent resolved infection – may have been protected against reinfection.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Houlihan et al. Daily confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 in HCWs at the hospital (boxes) and reported cases in London (red line). PCR negative participants who seroconverted are shown at the midpoint between baseline and follow-up serology tests. Among HCW at the hospital there were 42 new cases with positive PCR (yellow boxes) and 10 persons who seroconverted but were PCR negative (green boxes). This article was published in Lancet, Vol 396, Houlihan et al., Pandemic peak SARS-CoV-2 infection and seroconversion rates in London frontline health-care workers, Page e6-e7, Copyright Elsevier 2020. This article is currently available at the Elsevier COVID-19 resource center: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-centerexternal icon.

PEER-REVIEWED

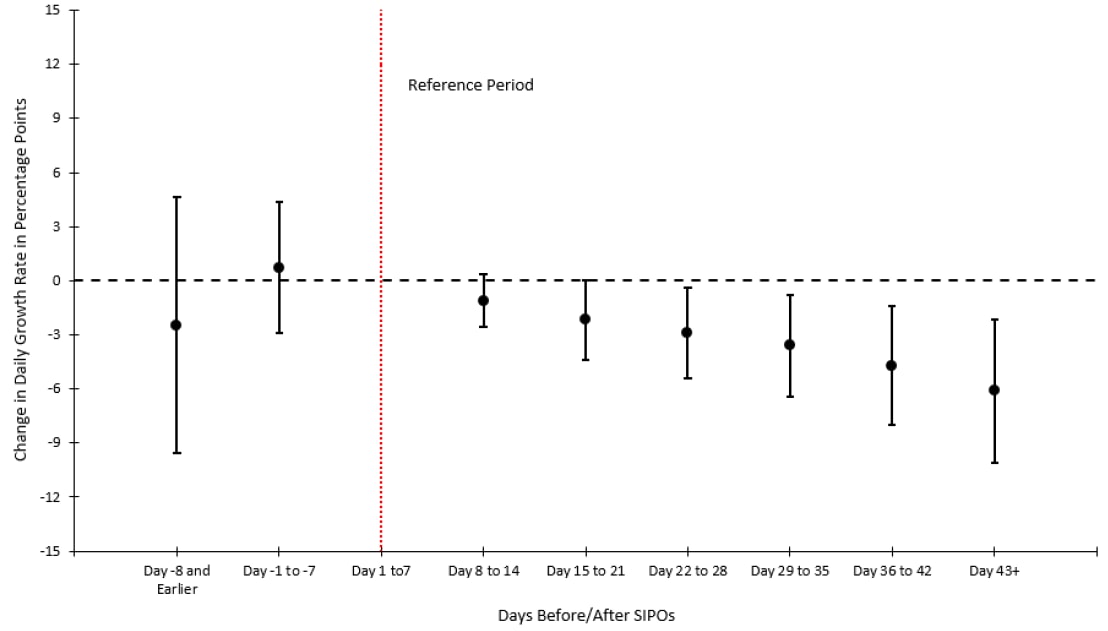

Shelter-in-place orders reduced COVID-19 mortality and reduced the rate of growth in hospitalizationsexternal icon. Lyu et al. Health Affairs (July 9, 2020).

Key findings:

- Six weeks after enacting shelter in place orders (SIPOs), there were significant reductions in COVID-19 mortality and hospitalizations.

- The average daily mortality growth rate declined by 6.1 percentage points (Figure).

- The average hospitalization growth rate declined by 8.4 percentage points.

- Models indicate the average daily death growth rate would have been 8.6% without SIPOs instead of 2.8% with SIPOs.

- By May 15, the projections suggest as many as 250,000-370,000 deaths and 750,000–840,000 hospitalizations were possibly averted with SIPOs in place.

Methods: An event study model examining effects of SIPOs on mortality (data from 42 states plus DC with statewide SIPOs and 5 without SIPOs) and hospitalizations (data from 22 states, 19 with statewide SIPOs and 3 with no SIPOs), between March 21 and May 15, 2020. Limitations: Underreporting of deaths and hospitalizations; no demographic or clinical data; results are not generalizable.

Implications: SIPOs can play a key role in slowing COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Lyu et al. Percentage change in the daily growth rate in COVID-19 mortality before and after enacting SIPOs (indicated by red line). The daily COVID-19 mortality growth rate declined by 2.9, 3.6, 4.7, and 6.1 percentage points within 22–28, 29–35, 36–42, and 43 or more days after enacting SIPOs, respectively. Used by permission from publisher.

PEER-REVIEWED

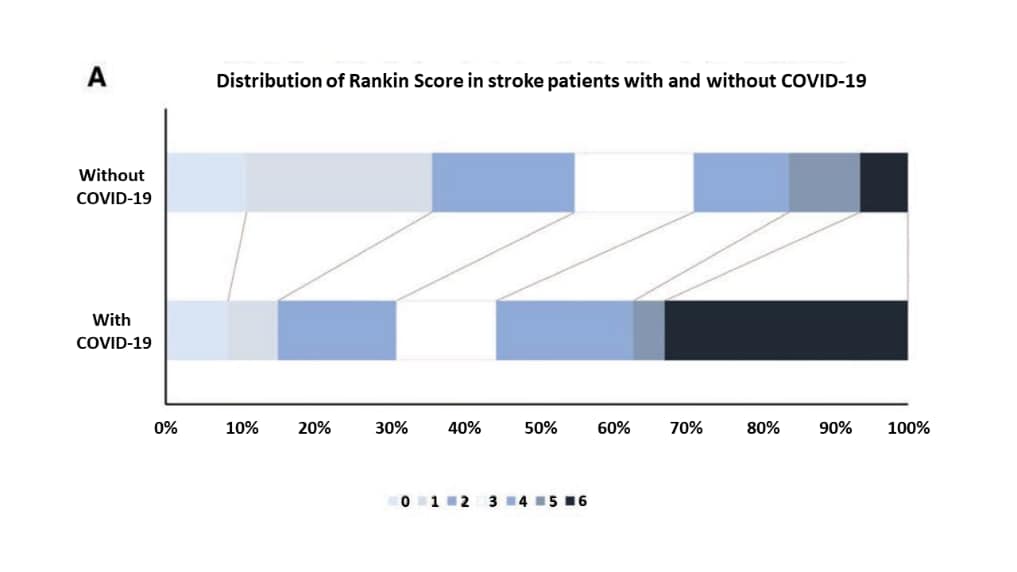

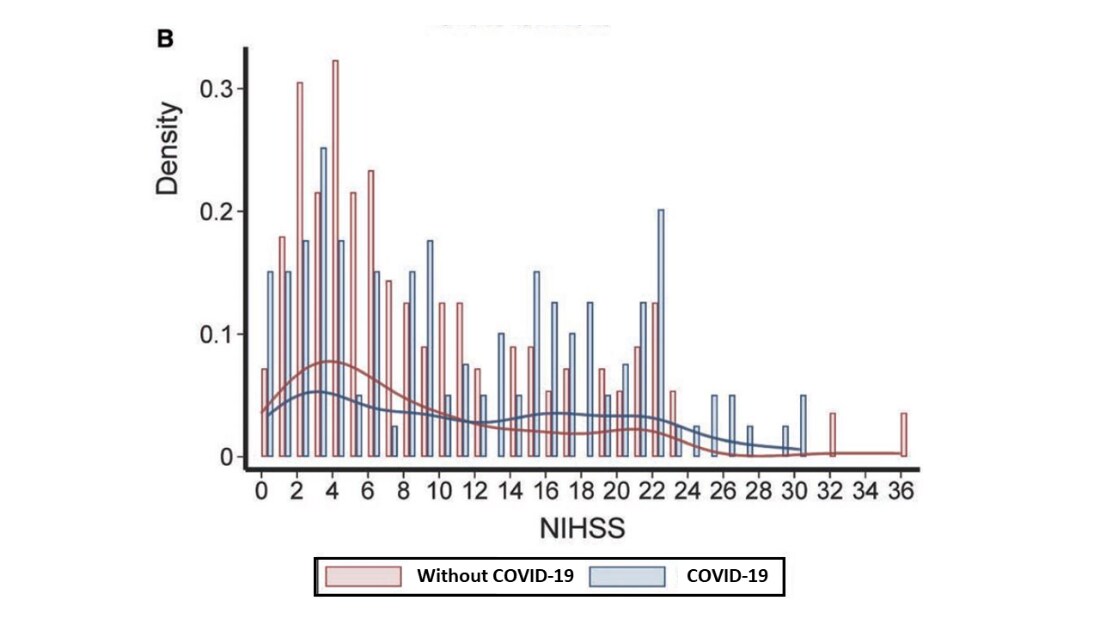

Characteristics and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and acute ischemic strokeexternal icon. Ntaios et al. Stroke (July 9, 2020).

Key findings:

- Acute ischemic strokes (AIS) are more severe with worse functional outcome and higher mortality among patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 than non-COVID-19 patients with ischemic strokes.

- Median modified Rankin Scale score in stroke patients was 4 (COVID-19) vs 2 (non-COVID-19), p <0.001 (Figure 1).

- Odds ratio of death among COVID-19 patients: 4.3 (95% CI 2.22–8.30) compared with patients with non-COVID-19.

- The median National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was 10 in patients with COVID-19 vs. 6 in non-COVID-19 patients, p = 0.03 (Figure 2).

Methods: Observational study of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 and acute ischemic stroke in 28 sites from 16 countries. Propensity score matching was used to compare patients with COVID-19 and AIS hospitalized between January 27 and May 19, 2020, to non-COVID-19 patients during 2003-2019 to assess stroke severity (estimated by the National Institute of Health Stroke Scaleexternal icon) and outcomes (assessed by the modified Rankin Scaleexternal icon). Limitations: Single site match cohort and potential unobserved indicators.

Implications: The association between COVID-19 and severe stroke highlights the urgent need for stroke awareness during the pandemic, especially since severe strokes have typically poor prognosis but can potentially be treated with focused care.

Figure 1

Note: Adapted from Ntaios et al. Distribution of the Rankin score in matched stroke patients with COVID-19 and patients without COVID-19. The modified Rankin Scale scores is used to measure the degree of disability in patients who had a stroke as follows: 0-No symptoms at all;1-No significant disability despite symptoms; able to carry out all usual duties and activities;2-Slight disability; unable to carry out all previous activities, but able to look after own affairs without assistance;3-Moderate disability; requiring some help, but able to walk without assistance;4-Moderately severe disability; unable to walk and attend to bodily needs without assistance;5-Severe disability; bedridden, incontinent and requiring constant nursing care and attention;6-Dead. Adapted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.: Ntaios et al. Characteristics and Outcomes in Patients With COVID-19 and Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2020;51:e254–e258. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031208external icon.

Figure 2

Note: Adapted from Ntaios et al. Matched stroke patients with COVID-19 and patients without COVID-19. Histogram (bar) and Kernel Density Estimates (curved line) of the National Institute of Health Stroke Scalepdf iconexternal icon scores. 0: No stroke symptoms; 1-4 Minor stroke; 5-15 Moderate Stroke; 16-20: Moderate to severe stroke; 21-42 Severe stroke. Adapted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.: Ntaios et al. Characteristics and Outcomes in Patients With COVID-19 and Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2020;51:e254–e258. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031208external icon.

- Klompas et al. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 theoretical considerations and available evidenceexternal icon. JAMA. Available evidence suggests that long-range aerosol-based transmission is not the dominant mode of SARS-CoV-2 transmission

- Brooks et al. Universal masking to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission—The time is nowexternal icon. JAMA. Emphasizes the importance of cloth face coverings that can help with national and global efforts against COVID-19.

- Zha et al. Clinical features and outcomes of adult COVID-19 patients co-infected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae.external icon Journal of Infection. The already elevated risk of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients is significantly increased by co-infection with Mycoplasma pneumonia.

- Elrashdy et al. On the potential role of exosomes in the COVID-19 reinfection/reactivation opportunityexternal icon. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. Hypothesizing the potential mechanisms for the re-appearance of viral RNA in recovered COVID-19 patients through a “Trojan horse” strategy where viral RNA material remains hidden within exosomes or extracellular vesicles.

- Morniroli et al. Human sialome and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: An understated correlation?external icon Frontiers in Immunology. An opinion piece describing how sialic acids could affect SARS-CoV-2 infection due to low selective-pressure.

- Yung et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from adults to childrenexternal icon. Journal of Pediatrics. Age-specific attack rates in children in households with confirmed COVID-19 in Singapore showed that children are most likely to be infected if the household index case was the mother.

- Rockett et al. Revealing COVID-19 transmission in Australia by SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing and agent-based modelingexternal icon. Nature Medicine. Added value of near real-time genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 in a subpopulation of infected patients in Australia.

- Gupta et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19external icon. Nature Medicine. A review of the extrapulmonary organ-specific pathophysiology, presentations and management considerations for patients with COVID-19 so clinicians and scientists can recognize and monitor therapeutic strategies.

- Santos et al. Economic, mental health, HIV prevention and HIV treatment impacts of COVID-19 and the COVID-19 response on a global sample of cisgender gay men and other men who have sex with menexternal icon. AIDS and behavior. A cross-sectional survey of gay men and other MSM highlighting COVID-19′s negative impact on access to HIV treatment and prevention services, economic consequences, and impact on mental health status.

- Barman et al. COVID-19 pandemic and its recovery time of patients in India: A pilot studyexternal icon. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. A study in India showing recovery time of Covid-19 patients will help planners with effective strategies to address the pandemic.

Disclaimer: The purpose of the CDC COVID-19 Science Update is to share public health articles with public health agencies and departments for informational and educational purposes. Materials listed in this Science Update are selected to provide awareness of relevant public health literature. A material’s inclusion and the material itself provided here in full or in part, does not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the CDC, nor does it necessarily imply endorsement of methods or findings. While much of the COVID-19 literature is open access or otherwise freely available, it is the responsibility of the third-party user to determine whether any intellectual property rights govern the use of materials in this Science Update prior to use or distribution. Findings are based on research available at the time of this publication and may be subject to change.