Introduction

‹View Table of Contents

Unintended pregnancy rates remain high in the United States; approximately 45% of all pregnancies are unintended, with higher proportions among adolescent and young women, women who are racial/ethnic minorities, and women with lower levels of education and income (1). Unintended pregnancies increase the risk for poor maternal and infant outcomes (2) and in 2010, resulted in U.S. government health care expenditures of $21 billion (3). Approximately half of unintended pregnancies are among women who were not using contraception at the time they became pregnant; the other half are among women who became pregnant despite reported use of contraception (4). Strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy include assisting women at risk for unintended pregnancy and their partners choose appropriate contraceptive methods and helping them use methods correctly and consistently to prevent pregnancy.

In 2013, CDC published the first U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (U.S. SPR), adapted from global guidance developed by the World Health Organization (WHO SPR), which provided evidence-based guidance on how to use contraceptive methods safely and effectively once they are deemed to be medically appropriate. U.S. SPR is a companion document to U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (U.S. MEC), which provides recommendations on safe use of contraceptive methods for women with various medical conditions and other characteristics (5). WHO intended for the global guidance to be used by local or national policy makers, family planning program managers, and the scientific community as a reference when they develop family planning guidance at the country or program level. During 2012–2013, CDC went through a formal process to adapt the global guidance for best implementation in the United States, which included rigorous identification and critical appraisal of the scientific evidence through systematic reviews, and input from national experts on how to translate that evidence into recommendations for U.S. health care providers (6). At that time, CDC committed to keeping this guidance up to date and based on the best available evidence, with full review every few years (6).

This document updates the 2013 U.S. SPR (6) with new evidence and input from experts. Major updates include 1) revised recommendations for starting regular contraception after the use of emergency contraceptive pills and 2) new recommendations for the use of medications to ease insertion of intrauterine devices (IUDs). Recommendations are provided for health care providers on the safe and effective use of contraceptive methods and address provision of contraceptive methods and management of side effects and other problems with contraceptive method use, within the framework of removing unnecessary medical barriers to accessing and using contraception. These recommendations are meant to serve as a source of clinical guidance for health care providers; health care providers should always consider the individual clinical circumstances of each person seeking family planning services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice for individual patients, who should seek advice from their health care providers when considering family planning options.

Updated Recommendations

Recommendations have been updated regarding when to start regular contraception after ulipristal acetate (UPA) emergency contraceptive pills:

- Advise the woman to start or resume hormonal contraception no sooner than 5 days after use of UPA, and provide or prescribe the regular contraceptive method as needed. For methods requiring a visit to a health care provider, such as depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), implants and IUDs, starting the method at the time of UPA use may be considered; the risk that the regular contraceptive method might decrease the effectiveness of UPA must be weighed against the risk of not starting a regular hormonal contraceptive method.

- The woman needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier contraception for the next 7 days after starting or resuming regular contraception or until her next menses, whichever comes first.

- Any nonhormonal contraceptive method can be started immediately after the use of UPA.

- Advise the woman to have a pregnancy test if she does not have a withdrawal bleed within 3 weeks.

New Recommendation

A new recommendation has been made for medications to ease IUD insertion:

- Misoprostol is not recommended for routine use before IUD insertion. Misoprostol might be helpful in select circumstances (e.g., in women with a recent failed insertion).

- Paracervical block with lidocaine might reduce patient pain during IUD insertion.

Since publication of the 2013 U.S. SPR, CDC has monitored the literature for new evidence relevant to the recommendations through the WHO/CDC continuous identification of research evidence (CIRE) system(7). This system identifies new evidence as it is published and allows WHO and CDC to update systematic reviews and facilitate updates to recommendations as new evidence warrants. Automated searches are run in PubMed weekly, and the results are reviewed. Abstracts that meet specific criteria are added to the web-based CIRE system, which facilitates coordination and peer review of systematic reviews for both WHO and CDC. In 2014, CDC reviewed all of the existing recommendations in the 2013 U.S. SPR for new evidence identified by CIRE that had the potential to lead to a changed recommendation. During August 27–28, 2014, CDC held a meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, of 11 family planning experts and representatives from partner organizations to solicit their input on the scope of and process for updating both the 2010 U.S. MEC and the 2013 U.S. SPR. The participants were experts in family planning and represented different provider types and organizations that represent health care providers. A list of participants is provided at the end of this report. The meeting related to topics to be addressed in the update of the U.S. SPR based on new scientific evidence published since 2013 (identified though the CIRE system), topics addressed at a 2014 WHO meeting to update global guidance, and suggestions CDC received from providers for the addition of recommendations not included in the 2013 U.S. SPR (e.g., from provider feedback through e-mail, public inquiry, and questions received at conferences). CDC identified one topic to consider adding to the guidance: the use of medications to ease IUD insertion (evidence question: “Among women of reproductive age, does use of medications before IUD insertion improve the safety or effectiveness of the procedure [ease of insertion, need for adjunctive insertion measures, or insertion success] or affect patient outcomes (pain, side effects) compared with non-use of these medications?”). CDC also identified one topic for which new evidence warranted a review of an existing recommendation: initiation of regular contraception after emergency contraceptive pills (evidence question: “Does ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception interact with regular use of hormonal contraception leading to decreased effectiveness of either contraceptive method?”). CDC determined that all other recommendations in the 2013 U.S. SPR were up to date and consistent with the current body of evidence for that recommendation.

In preparation for a subsequent expert meeting August 26–28, 2015, to review the scientific evidence for potential recommendations, CDC staff conducted independent systematic reviews for each of the topics being considered. The purpose of these systematic reviews was to identify evidence related to the common clinical challenges associated with the recommendations. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed for reporting systematic reviews (7,8), and strength and quality of the evidence were assigned using the system of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (9). When direct evidence was limited or not available, indirect evidence (e.g., evidence on surrogate outcomes) and theoretical issues were considered and either added to direct evidence within a systematic review or separately compiled for presentation to the meeting participants. Completed systematic reviews were peer reviewed by two or three experts and then provided to participants before the expert meeting. Reviews are referenced and linked throughout this document; the full reviews have been published and contain the details of each review, including systematic review question, literature search protocol, inclusion and exclusion criteria, evidence tables, and quality assessment. CDC staff continued to monitor new evidence identified through the CIRE system during the preparation for the August 2015 meeting.

During August 26–28, 2015, CDC held a meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, of 28 participants who were invited to provide their individual perspectives on the scientific evidence presented and to discuss potential recommendations that followed. Participants represented a wide range of expertise in family planning provision and research, and included obstetrician/gynecologists, pediatricians, family physicians, nurse practitioners, epidemiologists, and others with research and clinical practice expertise in contraceptive safety, effectiveness, and management. Lists of participants and potential conflicts of interest are provided at the end of this report. During the meeting, the evidence from the systematic review for each topic was presented, including direct evidence and any indirect evidence or theoretical concerns. Participants provided their perspectives on the translation of the evidence into recommendations that would meet the needs of U.S. health care providers. After the meeting, CDC determined the recommendations in this report, taking into consideration the perspectives provided by the meeting participants. Feedback also was received from four external reviewers, composed of health care providers who had not participated in the update meetings. These providers were asked to provide comments on the accuracy, feasibility, and clarity of the recommendations. Areas of research that need additional investigation also were considered during the meeting (10).

As with any evidence-based guidance document, a key challenge is keeping the recommendations up to date as new scientific evidence becomes available. Working with WHO, CDC uses the continuous identification of research evidence (CIRE) system to ensure that WHO and CDC guidance is based on the best available evidence and that a mechanism is in place to update guidance when new evidence becomes available (11). CDC will continue to work with WHO to identify and assess all new relevant evidence and determine whether changes in the recommendations are warranted. In most cases, U.S. SPR will follow any updates in the WHO guidance, which typically occurs every 5 years (or sooner if warranted by new data). In addition, CDC will review any interim WHO updates for their application in the United States. CDC also will identify and assess any new literature for the recommendations that are not included in the WHO guidance and will completely review the U.S. SPR every 5 years. Updates to the guidance can be found on the U.S. SPR website.

The recommendations in this report are intended to help health care providers address issues related to use of contraceptives, such as how to help a woman initiate use of a contraceptive method, which examinations and tests are needed before initiating use of a contraceptive method, what regular follow-up is needed, and how to address problems that often arise during use, including missed pills and side effects such as unscheduled bleeding. Each recommendation addresses what a woman or health care provider can do in specific situations. For situations in which certain groups of women might be medically ineligible to follow the recommendations, comments and reference to U.S. MEC are provided (5). The full U.S. MEC recommendations and the evidence supporting those recommendations were updated in 2016 (5) and are summarized in Appendix A.

The information in this document is organized by contraceptive method, and the methods generally are presented in order of effectiveness, from highest to lowest. However, the recommendations are not intended to provide guidance on every aspect of provision and management of contraceptive method use. Instead, they incorporate the best available evidence to address specific issues regarding common, yet sometimes complex, clinical issues. Each contraceptive method section generally includes information about initiation of the method, regular follow-up, and management of problems with use (e.g., usage errors and side effects). Each section first provides the recommendation and then includes comments and a brief summary of the scientific evidence on which the recommendation is based. The level of evidence from the systematic reviews for each evidence summary are provided based on the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force system, which includes ratings for study design (I: randomized controlled trials; II-1: controlled trials without randomization; II-2: observational studies; and II-3: multiple time series or descriptive studies), ratings for internal validity (good, fair, or poor), and categorization of the evidence as direct or indirect for the specific review question (9).

Recommendations in this document are provided for permanent methods of contraception, such as vasectomy and female sterilization, as well as for reversible methods of contraception, including the copper-containing intrauterine device (Cu-IUD); levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs (LNG-IUDs); the etonogestrel implant; progestin-only injectables; progestin-only pills (POPs); combined hormonal contraceptive methods that contain both estrogen and a progestin, including combined oral contraceptives (COCs), a transdermal contraceptive patch, and a vaginal contraceptive ring; and the standard days method (SDM). Recommendations also are provided for emergency use of the Cu-IUD and emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs).

For each contraceptive method, recommendations are provided on the timing for initiation of the method and indications for when and for how long additional contraception, or a back-up method, is needed. Many of these recommendations include guidance that a woman can start a contraceptive method at any time during her menstrual cycle if it is reasonably certain that she is not pregnant. Guidance for health care providers on how to be reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant also is provided.

For each contraceptive method, recommendations include the examinations and tests needed before initiation of the method. These recommendations apply to persons who are presumed to be healthy. Those with known medical problems or other special conditions might need additional examinations or tests before being determined to be appropriate candidates for a particular method of contraception. U.S. MEC might be useful in such circumstances (5). Most women need no or very few examinations or tests before initiating a contraceptive method although they might be needed to address other non-contraceptive health needs (12). Any additional screening needed for preventative health care can be performed at the time of contraception initiation and initiation should not be delayed for test results. The following classification system was developed by WHO and adopted by CDC to categorize the applicability of the various examinations or tests before initiation of contraceptive methods (13):

- Class A: These tests and examinations are essential and mandatory in all circumstances for safe and effective use of the contraceptive method

- Class B: These tests and examinations contribute substantially to safe and effective use, although implementation can be considered within the public health context, service context, or both. The risk for not performing an examination or test should be balanced against the benefits of making the contraceptive method available.

- Class C: These tests and examinations do not contribute substantially to safe and effective use of the contraceptive method.

These classifications focus on the relation of the examinations or tests to safe initiation of a contraceptive method. They are not intended to address the appropriateness of these examinations or tests in other circumstances. For example, some of the examinations or tests that are not deemed necessary for safe and effective contraceptive use might be appropriate for good preventive health care or for diagnosing or assessing suspected medical conditions. Systematic reviews were conducted for several different types of examinations and tests to assess whether a screening test was associated with safe use of contraceptive methods. Because no single convention exists for screening panels for certain diseases, including diabetes, lipid disorders, and liver diseases, the search strategies included broad terms for the tests and diseases of interest.

Summary charts and clinical algorithms that summarize the guidance for the various contraceptive methods have been developed for many of the recommendations, including when to start using specific contraceptive methods (Appendix B), examinations and tests needed before initiating the various contraceptive methods (Appendix C), routine follow-up after initiating contraception (Appendix D), management of bleeding irregularities (Appendix E), and management of IUDs when users are found to have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) (Appendix F). These summaries might be helpful to health care providers when managing family planning patients. Additional tools are available on the U.S. SPR website.

Many elements need to be considered individually by a woman, man, or couple when choosing the most appropriate contraceptive method. Some of these elements include safety, effectiveness, availability (including accessibility and affordability), and acceptability. Although most contraceptive methods are safe for use by most women, U.S. MEC provides recommendations on the safety of specific contraceptive methods for women with certain characteristics and medical conditions (5); a U.S. MEC summary (Appendix A) and the categories of medical eligibility criteria for contraception use (Box 1) are provided.

BOX 1. Categories of medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use

U.S. MEC 1 = A condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method.U.S. MEC 2 = A condition for which the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks.

U.S. MEC 3 = A condition for which the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method.

U.S. MEC 4 = A condition that represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used.

Source: CDC. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. MMWR 2016;65(No. RR-3).

Abbreviations: U.S. MEC = U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use.

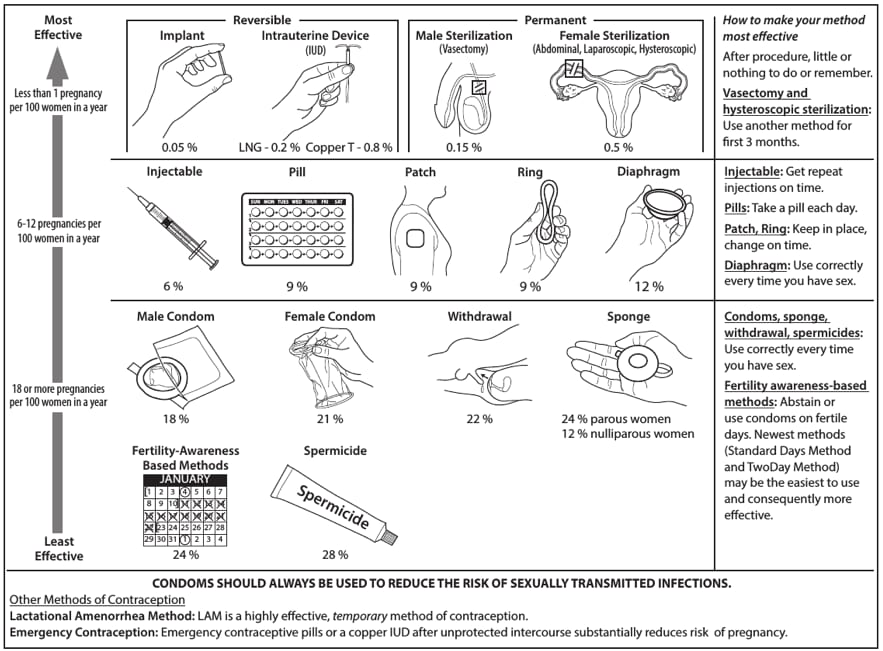

Contraceptive method effectiveness is critically important in minimizing the risk for unintended pregnancy, particularly among women for whom an unintended pregnancy would pose additional health risks. The effectiveness of contraceptive methods depends both on the inherent effectiveness of the method itself and on how consistently and correctly it is used (Figure 1). Both consistent and correct use can vary greatly with characteristics such as age, income, desire to prevent or delay pregnancy, and culture. Methods that depend on consistent and correct use by clients have a wide range of effectiveness between typical use (actual use, including incorrect or inconsistent use) and perfect use (correct and consistent use according to directions) (14). IUDs and implants are considered long-acting, reversible contraception (LARC); these methods are highly effective because they do not depend on regular compliance from the user. LARC methods are appropriate for most women, including adolescents and nulliparous women. All women should be counseled about the full range and effectiveness of contraceptive options for which they are medically eligible so that they can identify the optimal method.

In choosing a method of contraception, dual protection from the simultaneous risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) also should be considered. Although hormonal contraceptives and IUDs are highly effective at preventing pregnancy, they do not protect against STDs and HIV. Consistent and correct use of the male latex condom reduces the risk for HIV infection and other STDs, including chlamydial infection, gonococcal infection, and trichomoniasis (15). On the basis of a limited number of clinical studies, when a male condom cannot be used properly to prevent infection, a female condom should be considered (15). All patients, regardless of contraceptive choice, should be counseled about the use of condoms and the risk for STDs, including HIV infection (15). Additional information about prevention and treatment of STDs is available from the CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines (15).

Women, men, and couples have increasing numbers of safe and effective choices for contraceptive methods, including LARC methods such as IUDs and implants, to reduce the risk for unintended pregnancy. However, with these expanded options comes the need for evidence-based guidance to help health care providers offer quality family planning care to their patients, including assistance in choosing the most appropriate contraceptive method for individual circumstances and using that method correctly, consistently, and continuously to maximize effectiveness. Removing unnecessary barriers can help patients access and successfully use contraceptive methods. Several medical barriers to initiating and continuing contraceptive methods might exist, such as unnecessary screening examinations and tests before starting the method (e.g., a pelvic examination before initiation of COCs), inability to receive the contraceptive on the same day as the visit (e.g., waiting for test results that might not be needed or waiting until the woman’s next menstrual cycle to start use), and difficulty obtaining continued contraceptive supplies (e.g., restrictions on number of pill packs dispensed at one time). Removing unnecessary steps, such as providing prophylactic antibiotics at the time of IUD insertion or requiring unnecessary follow-up procedures, also can help patients access and successfully use contraception.

NOTE: New estimates of contraceptive effectiveness were published in 2018: Trussell J, Aiken ARA, Micks E, Guthrie KA. Efficacy, safety, and personal considerations. In: Hatcher RA, Nelson AL, Trussell J, Cwiak C, Cason P, Policar MS, Edelman A, Aiken ARA, Marrazzo J, Kowal D, eds. Contraceptive technology. 21st ed. New York, NY: Ayer Company Publishers, Inc., 2018.

Sources: Adapted from World Health Organization (WHO) Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP). Knowledge for health project. Family planning: a global handbook for providers (2011 update). Baltimore, MD; Geneva, Switzerland: CCP and WHO; 2011; and Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404.

* The percentages indicate the number out of every 100 women who experienced an unintended pregnancy within the first year of typical use of each contraceptive method.

Pages in this Report

- Table of Contents

- US SPR 2016

- ›Introduction

- How To Be Reasonably Certain that a Woman Is Not Pregnant

- Intrauterine Contraception

- Implants

- Injectables

- Combined Hormonal Contraceptives

- Progestin-Only Pills

- Standard Days Method

- Emergency Contraception

- Female Sterilization

- Male Sterilization

- When Women Can Stop Using Contraceptives

- Conclusion

- References

- Summary Chart of U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016

- When To Start Using Specific Contraceptive Methods

- Examinations and Tests Needed Before Initiation of Contraceptive Methods

- Routine Follow-Up After Contraceptive Initiation

- Management of Women with Bleeding Irregularities While Using Contraception

- Management of Intrauterine Devices When Users are Found To Have Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- Participants