Are There Specific Considerations for Different Patient Populations?

Oral PrEP with emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF, brand name Truvada® or generic equivalent) can be prescribed off-label using “2-1-1” dosing for adult MSM. This is also known as event-driven, intermittent, on-demand, or coitally timed PrEP. When using 2-1-1 dosing, the patient takes F/TDF doses based on when they plan to have sex: two pills 2–24 hours before sex, one pill 24 hours after the first two-pill dose, and one pill 48 hours after the first two-pill dose.

Off-label 2-1-1 dosing is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, it can be prescribed to MSM who meet the following criteria:

- Request non-daily dosing.

- Have sex infrequently (e.g., less often than once a week).

- Can anticipate sex (or delay sex) to permit the doses at least 2 hours prior to sex.

2-1-1 dosing should not be prescribed for

- MSM who might have problems adhering to a complex dosing regimen (e.g., adolescents and patients with an active substance use disorder).

- People other than adult MSM.

- People with active hepatitis B infection.

Injectable PrEP may be appropriate for people who have problems taking oral PrEP as prescribed.

Transgender and nonbinary people who use gender-affirming hormones and have HIV risk factors can use PrEP. There are no known drug conflicts between PrEP and hormone therapy, and there is no reason why the drugs cannot be taken at the same time.

There are three PrEP regimens approved for transgender women and other people assigned male at birth:

- Daily oral F/TDF

- Daily oral F/TAF

- CAB injections every two months

There are two PrEP regimens approved for transgender men and other people assigned female at birth who may have receptive vaginal sex:

- Daily oral F/TDF

- CAB injections every two months

Emtricitabine with tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF, brand name Descovy®) has not yet been studied for HIV prevention among people assigned female at birth who could get HIV through receptive vaginal sex.

PrEP and birth control

PrEP medications that are approved for use by people with the potential for pregnancy can be used with birth control. There are no known interactions between PrEP and hormone-based birth control methods, such as the pill, patch, ring, shot, implant, and intrauterine device (IUD).

PrEP and HIV during conception, pregnancy, and breast/chestfeeding

There are two recommended PrEP regimens for people who may become pregnant:

- Oral PrEP. F/TDF as PrEP is considered generally safe for people who are pregnant or breast/chestfeeding.3–5 Current perinatal antiretroviral treatment guidelines recommend PrEP with T/TDF for people who may become pregnant, those who are pregnant, and those who are breast/chestfeeding 1-3.

- Injectable PrEP. Currently, the published data on CAB-exposed pregnancies among pregnant people without HIV are sparse.4 CAB injections may be initiated or continued in people who may become pregnant if the patient and provider agree that the benefits outweigh potential risks.

Concerns around fetal and infant exposure to PrEP medications

Discuss PrEP and other HIV-prevention methods with all your patients who may become pregnant, including potential risks and benefits during conception, pregnancy, and breast/chestfeeding.5

If a patient who is or may become pregnant has concerns, talk about those concerns with the patient. Then, decide together if the risk of getting HIV through sex or injection drug use is sufficiently high to use PrEP, knowing that pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of getting HIV.6,7

The Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry confidentially collects data on pre- and perinatal exposure to PrEP medications. The goal of this registry is to provide early warning of any negative effects of these medications on fetal and infant development. Providers are strongly encouraged to submit information prospectively and anonymously about any pregnancies in which PrEP is used to the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry website.

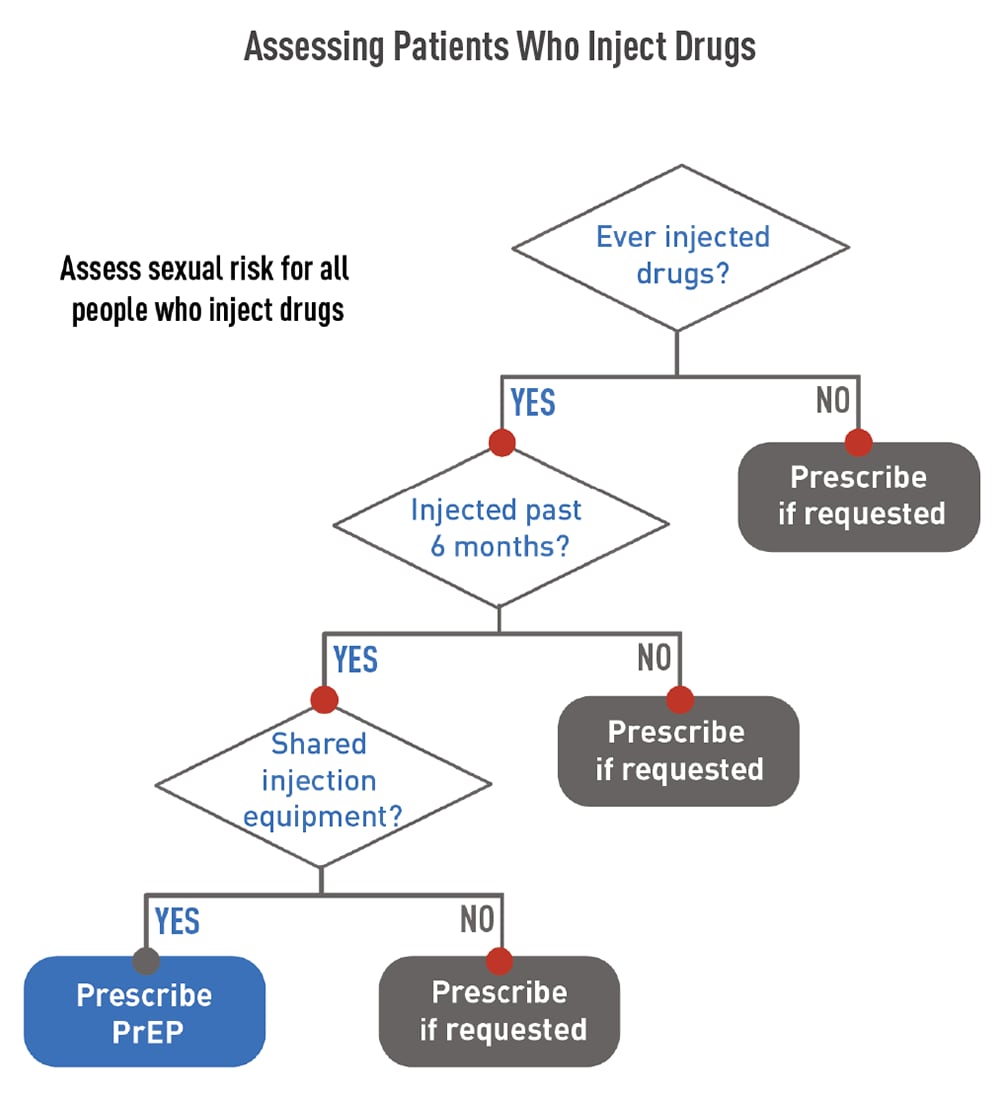

People who inject drugs that are not prescribed to them should be offered PrEP. Oral PrEP has been shown to reduce the risk of getting HIV from injection drug use by at least 74%, when taken as prescribed.8,9 The US Preventive Services Task Force’s grade IA recommendation for prescribing PrEP with cabotegravir (CAB, brand name Apretude®) states that CAB is recommended for adults who may get HIV through sex. Because most people who inject drugs are also sexually active, they should be assessed for sexual risk and provided the option of CAB for PrEP when indicated.

Use the flowchart shown to the right to assess when to prescribe PrEP to patients who inject drugs.

Substance use disorder treatment and behavioral health services

Provide your patients who inject drugs and use PrEP with access to substance use disorder treatment services during regular follow-up appointments:

- For patients on oral PrEP: Provide access at least every 3 months.

- For patients on injectable PrEP: Provide access at least every 2 months (beginning in month 3).

Assess your patients who inject drugs to identify any needs for cognitive or behavioral counseling or mental health or social services. Providing or referring your patients to these services can help them manage their HIV risk factors.

Offer medication-assisted treatment to your patients who inject opioids. This can be done within the PrEP clinical setting (e.g., through the provision of daily oral buprenorphine or naltrexone) or by referral to a substance use disorder treatment clinic (e.g., methadone program). Find local substance use disorder treatment resources online on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services’ Locator Map.

Access to sterile injection equipment

Not all patients who inject drugs are able or ready to engage in substance use treatment. Provide these patients with access to sterile injection equipment to help reduce their exposure to HIV and other infectious agents (e.g., hepatitis C). This should be done as part of your regular follow-up appointments with patients using PrEP:

- For patients on oral PrEP: Provide access at least every 3 months.

- For patients on injectable PrEP: Provide access at least every 2 months (beginning in month 3).

You can use the following methods to provide access to sterile injection equipment:

- Link patients to syringe service programs, if they are legal and available in your area.

- Prescribe syringes.

- Advise patients to purchase syringes from pharmacies without a prescription, if it is legal in your area.

PrEP is recommended for adolescents without HIV who weigh at least 77 pounds (35 kilograms). While there has been less research on PrEP use among adolescents, available data suggest that PrEP is safe and effective for HIV prevention among adolescent patients.10

- Daily oral F/TDF and F/TAF are FDA-approved PrEP options for adolescents. F/TAF has not yet been studied for HIV prevention for people assigned female at birth who could get HIV through receptive vaginal sex.

- CAB has not been studied in men or women <18 years of age. These studies are underway. However, until CAB is determined to be safe for this population and approved by the FDA, CAB injections are not recommended for adolescents <18 years old.

Taking a sexual and substance use history is essential to understanding your adolescent patients’ risk of HIV and whether PrEP is right for them. Providers should offer PrEP to any adolescent who reports HIV risk factors relating to sex or injecting drugs.

Legal considerations

Laws and regulations that may be relevant for PrEP-related services provided to adolescent minors (including HIV testing) differ by jurisdiction. Such laws and regulations may affect consent, confidentiality, parental disclosure, and circumstances requiring reporting to local agencies. When considering providing PrEP to an adolescent <18 years old, consult local laws, regulations, and policies that may apply. Adolescents may be concerned about confidentiality, which can prevent them from seeking the support they need. To build trust with adolescent patients, explicitly discuss confidentiality based on local laws and policies and the methods you will use to ensure confidentiality is maintained to the extent permitted. Visit CDC’s page on relevant laws and policies to learn more.

If the law permits, allow adolescent patients who would benefit from PrEP to decide for themselves whether to take it. When it is safe and appropriate, encourage them to include others, such as parents and guardians, in the conversation about PrEP.10

PrEP must be taken as prescribed for it to work. Talk with your adolescent patients about the importance of taking their medication as prescribed and strategies to help them maintain medication adherence. Because adolescents often experience difficulties with adherence, your adolescent patients on PrEP may benefit from more frequent, supportive interactions.11–13

Bone density changes

Data have shown bone density changes in young MSM during PrEP use and after completing a PrEP trial period of 48 weeks. Findings indicate decreased bone mineral density during the use of F/TDF as PrEP, with larger declines in those ages 15–19 years than in those ages 20–22 years. While men ages 18–22 years had full improvement during the 48 weeks after PrEP use stopped, declines persisted in younger men.14 These bone density changes were more frequently seen in young men with greatest adherence (i.e., highest drug exposure).14 Because differences in pharmacodynamics suggest less bone effect with F/TAF than with F/TDF, consider prescribing F/TAF to adolescent male patients initiating PrEP. The likelihood of long-term bone health should be weighed against the potential benefit of providing PrEP for an individual adolescent with HIV risk factors.

Kidney function must be considered when working with your patients to select an appropriate PrEP regimen. Assess your patients’ kidney function before they start oral PrEP and then at regular follow-up appointments. Kidney function assessments are not needed for patients receiving CAB injections.

Kidney function requirements for patients taking oral PrEP

When used as PrEP, tenofovir can cause decreases in kidney function that are generally small, usually remain within the normal range, and of no known clinical significance.15,16 These small decreases typically return to earlier levels when the patient stops taking the medication.2,3 Occasional cases of acute kidney failure, including Fanconi’s syndrome, have occurred.16–19 Therefore, all patients considered for oral PrEP must have their kidney function assessed at PrEP initiation and periodically thereafter so that oral PrEP can be stopped if the medication negatively affects kidney function.

Assess kidney function using the Cockcroft-Gault formula with the patient’s serum creatinine value to calculate their estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl)20:

- F/TDF and F/TAF are approved for use in people with eCrCl >60 mL/min.

- F/TAF is approved for use in people with eCrCl ≥30 mL/min.

Patients without HIV whose sexual partners have HIV can use PrEP to protect themselves from HIV. CAB injections or daily oral PrEP are recommended options for these patients, especially if the patient’s partner or partners may not be virally suppressed.

When assessing indications for PrEP use in mixed-HIV-status sexual partners, ask about the treatment and viral load status of the partner with HIV, if the partner without HIV knows it. People with HIV who achieve and maintain a plasma HIV RNA viral load <200 copies/mL with antiretroviral therapy won’t transmit HIV.21 This is sometimes referred to as Undetectable=Untransmittable (U=U) or treatment as prevention.22

PrEP may be indicated for the partner without HIV if any of the following criteria are met:

- The partner with HIV has been inconsistently virally suppressed or their viral load status is unknown.

- The partner without HIV has other sexual partners, especially if their HIV status is unknown.

- The partner without HIV wants the additional reassurance of protection that PrEP can provide.

PrEP should not be withheld from patients without HIV who request it, even if their sexual partner with HIV is reported be virally suppressed. Several studies using viral genotyping have documented instances where a person without HIV acquired HIV from having sex with a person with HIV outside the relationship with the partner known to have HIV.23

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update: clinical providers’ supplement. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2021.pdf

2 Gilead Sciences. Truvada package insert. Published 2016. Accessed August 8, 2016. https://www.gilead.com/~/media/files /pdfs/medicines/hiv/truvada/truvada_pi.pdf

3 Teva Pharmaceuticals. Emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate tablets package insert. Published 2020. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.tevahivgenerics.com/globalassets/emtricitabine/pdfs/tg-42450_emtricitabine-and-tenofovir-disoproxil-fumarate-tablets-promo-pi-for-use-electronically.pdf

4 Tolley EE, Zangeneh SZ, Chau G, et al. Acceptability of long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB LA) in HIV-uninfected individuals: HPTN 077. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(9):2520-2531.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC7423859/

5 Lampe MA, Smith DK, Anderson GJE, et al. Achieving safe conception in HIV-discordant couples: the potential role of oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States. American Journal of Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):e1-e8. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5514a1.htm

6 Thompson KA, Hughes J, Baeten, JM, et al. Increased risk of female HIV-1 acquisition throughout pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective per-coital act analysis among women with HIV-1 infected partners. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:16-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6561341/

7 Mugo NR, Heffron R, Donnell D, et al. Increased risk of HIV-1 transmission in pregnancy: a prospective study among African HIV-1 serodiscordant couples. AIDS. 2011;25(15):1887-1895. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3173565/

8 Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083-2090. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673613611277

9Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. The impact of adherence to preexposure prophylaxis on the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. AIDS. 2015;29(7):819-824. https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2015/04240/The_impact_of_adherence_to_preexposure_prophylaxis.8.aspx

10 Tanner MR, Miele P, Carter W, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for prevention of HIV acquisition among adolescents: clinical considerations, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020:69(3):1-12. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/rr/rr6903a1.htm

11 Myers JJ, Dufour M-SK, Koester KA, et al. Adherence to PrEP among young men who have sex with men participating in a sexual health services demonstration project in Alameda County, California. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(4):406-413. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2019/08010/Adherence_to_PrEP_Among_Young_Men_Who_Have_Sex.7.aspx

12 Gray WN, Netz M, McConville A et al. Medication adherence in pediatric asthma: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53(5):668-684 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ppul.23966

13 Venditti EM, Tan K, Chang N, et al. Barriers and strategies for oral medication adherence among children and adolescents with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:24-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5955779/

14 Havens PL, Perumean-Chaney SE, Patki A, et al. Changes in bone mass after discontinuation of preexposure prophylaxis with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine in young men who have sex with men: extension phase results of Adolescent Trials Network protocols 110 and 113. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(4):687-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7319267/

15 Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. Renal function of participants in the Bangkok tenofovir study—Thailand, 2005–2012. Clin infect Dis. 2014;59(5):716-724. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/59/5/716/2895408?login=true

16 Mugwanya KK, Wyatt C, Celum C, et al. Changes in glomerular kidney function among hiv-1-uninfected men and women receiving emtricitabine–tenofovir disoproxil fumarate preexposure prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):246-254. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4354899/

17 Antoni G, Tremblay C, Charreau I, et al. On-demand PrEP with TDF/FTC remains highly effective among MSM with infrequent sexual intercourse: a sub-study of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Presented at: IAS Conference on HIV Science; July 23-27, 2017; Paris, France.

18 Saag MS, Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2018;320(4):379-396. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6415748/

19 Tang EC, Vittinghoff E, Anderson PL, et al. Changes in Kidney Function Associated With Daily Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine for HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Use in the United States Demonstration Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(2):193-198. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5762266/

20 Wassner C, Bradley N, Lee Y. A review and clinical understanding of tenofovir: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus tenofovir alafenamide. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2020;19:2325958220919231. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7163232/

21 Attia S, Egger M, Muller M, et al. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(11):1397-404. https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2009/07170/Sexual_transmission_of_HIV_according_to_viral_load.13.aspx

22 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evidence of HIV treatment and viral suppression in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV: technical fact sheet. 2018. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/evidence-of-hiv-treatment.html

23 Cohen MS, McCauley M, Gamble TR. HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):99-105. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3486734/