Angiostrongyliasis, Abdominal

[Angiostrongylus costaricensis]

Causal Agent

The nematode (roundworm) Angiostrongylus (=Parastrongylus) costaricensis is the causal agent of abdominal angiostrongyliasis (intestinal angiostrongyliasis). The related species A. cantonensis (rat lungworm), which causes neural angiostrongyliasis, is discussed here.

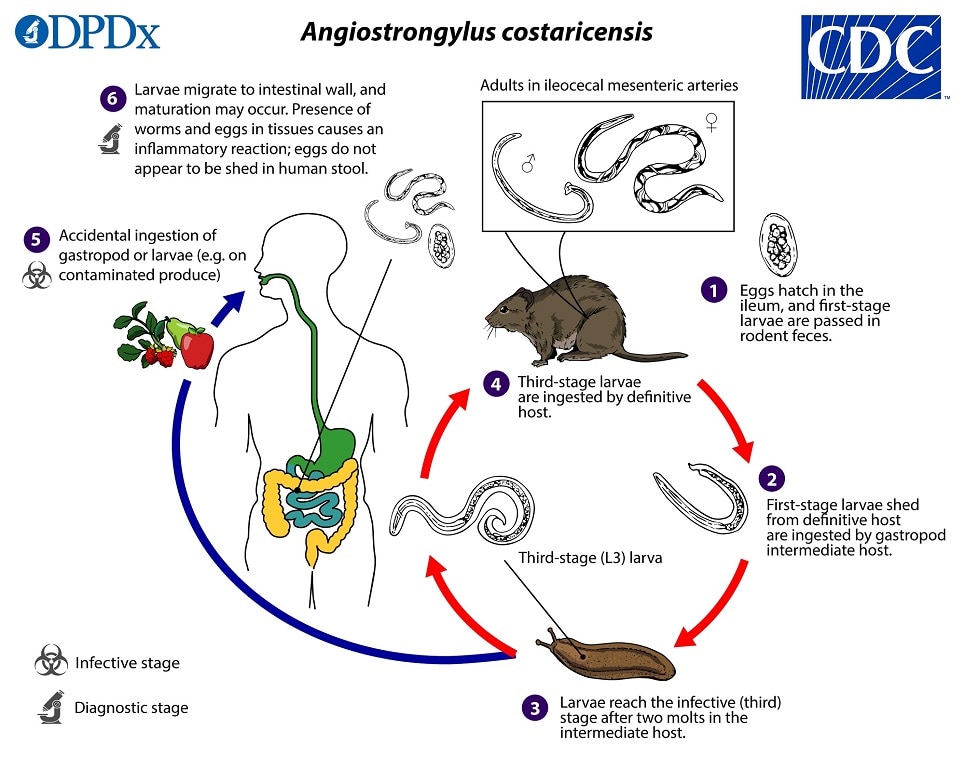

Life Cycle

and are ingested by a suitable gastropod intermediate host

and are ingested by a suitable gastropod intermediate host  . After two molts, third-stage (L3) larvae are produced, which are infective to mammalian hosts

. After two molts, third-stage (L3) larvae are produced, which are infective to mammalian hosts  . When the gastropod is ingested by the definitive host, the L3 larvae migrate to the lymphatic vessels of the abdominal cavity and develop into adults

. When the gastropod is ingested by the definitive host, the L3 larvae migrate to the lymphatic vessels of the abdominal cavity and develop into adults  . Some L3 larvae may also be shed into the environment by snails via slime trails, though it is not known if ingestion of these larvae represents a major transmission route. These young adults then migrate from the lymphatics to the mesenteric arteries, where they become sexually mature, approximately 24 days after larvae are ingested. Humans become infected by eating raw or undercooked gastropods that contain third-stage larvae or by eating food items contaminated with gastropod tissue or perhaps larvae shed in slime

. Some L3 larvae may also be shed into the environment by snails via slime trails, though it is not known if ingestion of these larvae represents a major transmission route. These young adults then migrate from the lymphatics to the mesenteric arteries, where they become sexually mature, approximately 24 days after larvae are ingested. Humans become infected by eating raw or undercooked gastropods that contain third-stage larvae or by eating food items contaminated with gastropod tissue or perhaps larvae shed in slime  . In humans, larvae undergo their usual migration and may reach sexual maturity and produce eggs (and L1 larvae) (unlike A. cantonensis)

. In humans, larvae undergo their usual migration and may reach sexual maturity and produce eggs (and L1 larvae) (unlike A. cantonensis)  . The presence of larvae, adult worms, and eggs causes a local inflammatory reaction in the intestinal wall. Parasites and eggs are usually degenerated by this host reaction, and eggs do not appear to be shed in human stool.

. The presence of larvae, adult worms, and eggs causes a local inflammatory reaction in the intestinal wall. Parasites and eggs are usually degenerated by this host reaction, and eggs do not appear to be shed in human stool.

Hosts

The main definitive host for A. costaricensis is the hispid cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus); but adult worms have been found in other rodent species, such as black rats (Rattus rattus), short-tailed zygodonts (Zygodontomys brevicauda), spiny pocket mice (Heteromys adspersus), and pygmy rice rats (Oligoryzomys fulvescens). Slugs in the families Veronicellidae and Limacidae are the typical intermediate hosts.

Aberrant abdominal infections have been documented in humans, non-human primates, and other mammals, including raccoons and one opossum.

Geographic Distribution

Abdominal angiostrongyliasis has mainly been reported from parts of Latin America and the Caribbean. Although A. costaricensis has been found in various animals in the southern United States, the sporadic human cases identified in the United States are thought to have been travel associated.

Clinical Presentation

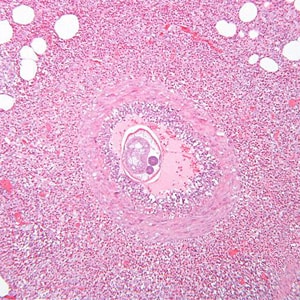

The clinical manifestations of abdominal angiostrongyliasis (A. costaricensis infection) arise from the parasite’s invasion of the gastrointestinal wall, and may mimic those of other conditions, such as appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, or Meckel’s diverticulum. Eosinophilia is commonly noted. Intestinal obstruction, perforation, and other complications may occur, as may ectopic infection (e.g., in the liver).

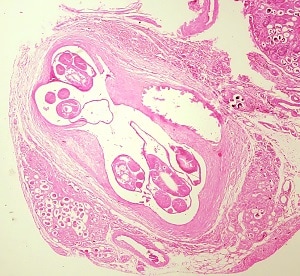

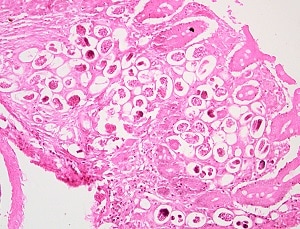

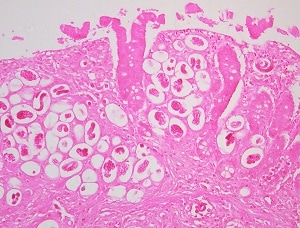

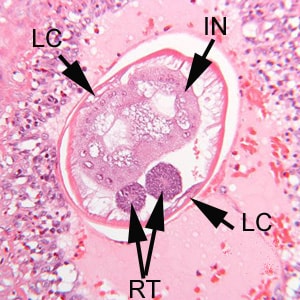

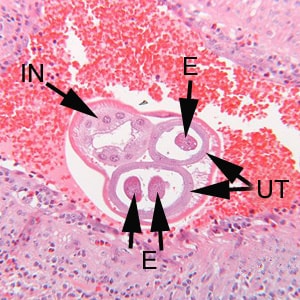

In humans, Angiostrongylus eggs and larvae remain sequestered in tissues and do not appear to be excreted in stool. A. costaricensis infections are predominantly abdominal; both eggs and larvae (occasionally adult worms) can be identified in biopsy or surgical specimens of intestinal tissue, where the eggs and larvae typically are engulfed in giant cells and/or granulomas.

The larvae of A. costaricensis in tissue sections need to be distinguished from larvae of Strongyloides . A. costaricensis first-stage (L1) larvae tend to be slightly smaller in diameter than S. stercoralis third-stage (L3) larvae and have single lateral alae, whereas S. stercoraliss L3 larvae have minute double lateral alae. The alae can be difficult to discern in most histologic sections. However, the presence of granulomas containing thin-shelled eggs and/or larvae generally serves to distinguish A. costaricensis infections from Strongyloides infections.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosis of abdominal angiostrongyliasis (A. costaricensis infection) is based on finding eggs, larvae, or adult worms in histologic sections. The patient’s travel/exposure history may prompt consideration of the diagnosis.

Molecular Diagnosis

No molecular tests specific for A. costaricensis are available. However, A. costaricensis can be identified in tissue by conventional PCR followed by DNA sequencing analysis.

Laboratory Safety

Standard precautions for the examination of histologic sections apply. Infectious L3 larvae are not encountered in a diagnostic laboratory setting.

Suggested Reading

Miller, C.L., Kinsella, J.M., Garner, M.M., Evans, S., Gullett, P.A. and Schmidt, R.E., 2006. Endemic infections of Parastrongylus (= Angiostrongylus) costaricensis in two species of nonhuman primates, raccoons, and an opossum from Miami, Florida. Journal of Parasitology, 92(2), pp.406-408.

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.