|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

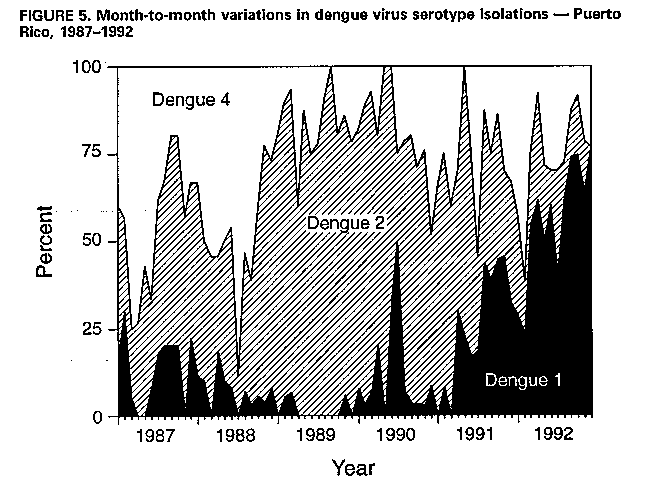

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Dengue Surveillance -- United States, 1986-1992Jose G. Rigau-Perez, M.D., M.P.H. Duane J. Gubler, Sc.D.

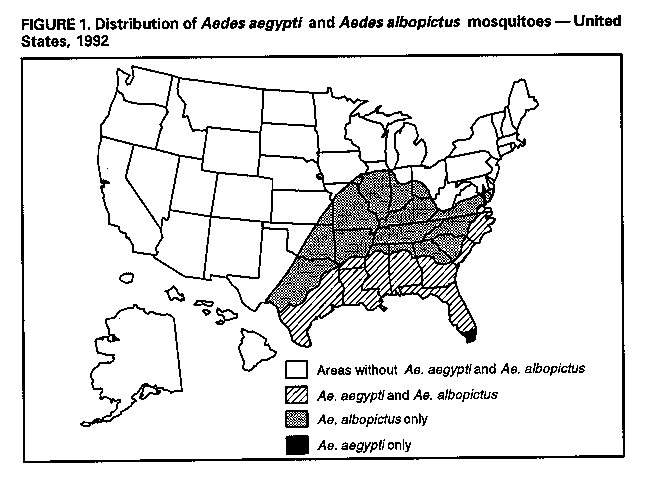

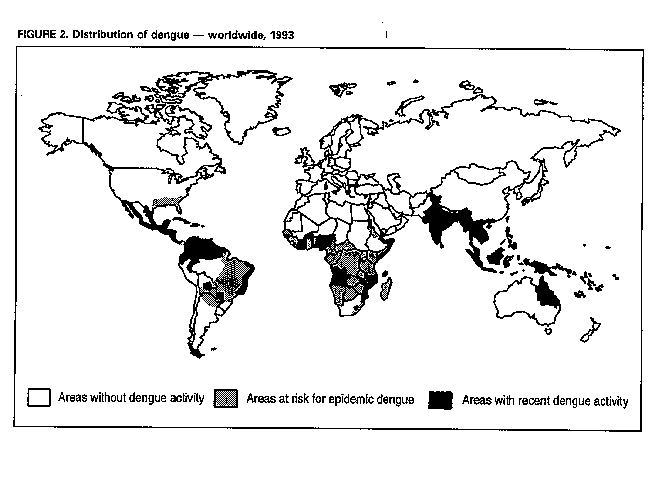

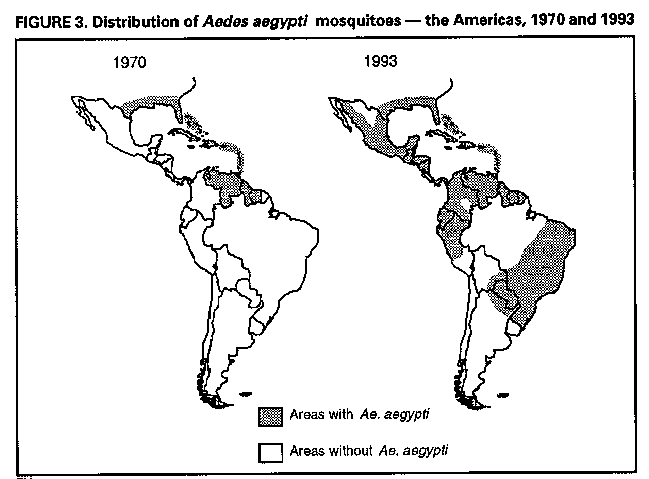

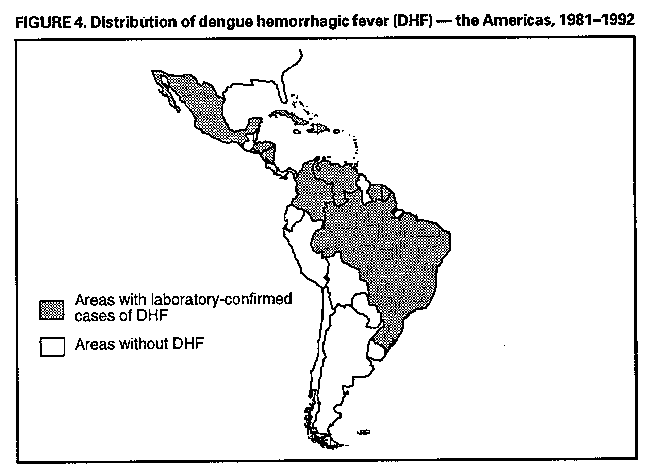

Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases National Center for Infectious Diseases Abstract Problem/Condition: Dengue is an acute, mosquito-transmitted viral disease characterized by fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, rash, nausea, and vomiting. The worldwide incidence of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS) increased from the mid-1970s through 1992. Although dengue is not endemic to the 50 United States, it presents a risk to U.S. residents who visit dengue-endemic areas. Reporting Period Covered: 1986-1992. Description of System: Dengue surveillance in the 50 United States and the U.S. Virgin Islands relies on provider-initiated reports to state health departments. State health departments then submit clinical information and serum samples to CDC for diagnostic confirmation of disease among U.S. residents who become ill during or after travel to dengue-endemic areas and among residents of the U.S. Virgin Islands. In Puerto Rico, an active, laboratory-based surveillance program receives serum specimens from ambulatory and hospitalized patients throughout the island, clinical reports on hospitalized cases, and copies of death certificates that list dengue as a cause of death. Laboratory diagnosis relies on virus isolation or serologic diagnosis of disease (i.e., IgM or IgG antibodies against dengue viruses). Results: In 1986, the first indigenous transmission of dengue in the United States in 6 years occurred in Texas; from the time of that incident through 1992, however, no further endemic transmission was reported. During 1986- 1992, CDC processed serum samples from 788 residents of 47 states and the District of Columbia. Among these 788 residents, 157 (20%) cases of dengue were diagnosed serologically or virologically. Of the 157 patients, 71 (45%) had visited Latin America or the Caribbean; 63 (40%), Asia and the Pacific; seven (4%), Africa; and nine (6%), several continents. All four dengue virus serotypes (DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3, and DEN-4) were isolated from travelers to Asia and the Pacific; however, travelers to the Americas acquired infections with only DEN-1, DEN-2, or DEN-4. Even though the number of laboratory- diagnosed dengue infections among travelers was small, severe and fatal disease was documented. In the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, three serotypes (DEN-1, DEN-2, and DEN-4) circulated during 1986-1992. In Puerto Rico, disease transmission was characterized by a cyclical pattern, with peaks in incidence occurring during months with higher temperatures and humidity (usually from September through November). The highest incidence of laboratory-diagnosed disease (1.2 cases per 1,000 population) occurred among persons less than 30 years of age; rates were similar for males and females. During 1986-1991, small numbers of laboratory-diagnosed DHF cases (range: 6- 17 cases) were reported each year. Interpretation: The increase in dengue incidence throughout the tropics presents a risk both to travelers and to residents in areas of the United States where Aedes aegypti mosquito infestations occur. Actions: The emphasis for dengue prevention is on sustainable, community- based mosquito control, with limited reliance on chemical larvicides and adulticides. Travelers to tropical areas can reduce their risk for dengue infection by taking appropriate precautionary measures to avoid mosquito bites (e.g., use of mosquito repellents, protective clothing, and spray insecticides). Physicians should consider dengue in the differential diagnosis of all patients who have symptoms compatible with dengue and who reside in or have visited tropical areas. Suspected dengue cases should be reported to the respective state or territorial health department, and clinical summaries and serum samples obtained from persons with suspected dengue should be sent for confirmation through the state health department laboratory to the Dengue Branch of CDC's National Center for Infectious Diseases. INTRODUCTION Dengue fever is an acute, mosquito-transmitted viral disease charac- terized by fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Infections are caused by any of four virus serotypes (DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3, and DEN-4). Although dengue is not endemic in the 50 United States, it presents a risk to U.S. residents who visit dengue-endemic areas throughout the world. More than 400 cases of introduced dengue were reported for 1977 through 1992 (1-8). Two competent mosquito vectors (Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus) are found in the southeastern states, and both could possibly transmit an introduced virus (Figure_1) (9-11). Most dengue infections result in relatively mild illness, but some can produce dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), which is characterized by fever, low platelet count, minimal to severe hemorrhagic manifestations, and excessive capillary permeability. If any sign of circulatory failure is evident, the condition is referred to as dengue shock syndrome (DSS). The fatality rate for patients with DSS may be high (12%-44%) (12). Dengue is endemic in most tropical areas throughout the world (Figure_2), but DHF and DSS are reported most commonly in Southeast Asia. Ae. aegypti is the principal vector mosquito for epidemic dengue. Although this species was nearly eradicated from the Americas in the 1960s, it is now found in all countries of the region except Bermuda, Canada, the Cayman Islands, Chile, and Uruguay (Figure_3). Dengue epidemics were relatively infrequent in the Americas before 1977, but the disease is now endemic in the Caribbean and most countries of Central and South America. Three of the four serotypes (DEN-1, DEN-2, and DEN-4) have been circulating in the Americas since 1981, but DEN-3 transmission has not occurred in the region since 1977 (13,14). The first case of DHF with laboratory-diagnosed dengue in the Americas was detected in Puerto Rico in 1975 (15). An epidemic of DHF (caused by DEN-2) in Cuba in 1981 resulted in greater than 10,000 cases of severe hemorrhagic fever and 158 deaths. From the time of the 1981 epidemic through 1992, sporadic cases of DHF were reported in most countries in the Caribbean region and from Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Suriname, and Venezuela (Figure_4). During 1984-1992, dengue epidemics with associated cases of DHF occurred in Aruba, Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, St. Lucia, and Venezuela. Cuba is the only country of the region that has eliminated dengue as a health problem, through the near eradication of Ae. aegypti on the island. In October 1993, a dengue fever epidemic occurred in Costa Rica, which had maintained an Aedes-aegypti-free territory for many years but was recently reinfested with the mosquito. Panama, which had maintained low levels of mosquito populations and had prevented the occurrence of endemic dengue, also reported locally acquired disease in late 1993. The worldwide incidence of DHF/DSS has increased substantially since the mid-1970s, primarily because of larger epidemics and an expanding distri- bution of disease in Asia (14). In China, epidemic dengue fever occurred in 1978 for the first time in greater than 35 years. In Taiwan, an epidemic occurred in 1981. All four serotypes were identified in both countries, and China experienced its first epidemic of DHF/DSS in 1985 (16). In western Asia, major epidemics of DHF/DSS occurred for the first time in India (1982), the Republic of Maldives (1985), and Sri Lanka (1989) (14). In most countries of Southeast Asia, dengue is hyperendemic (with all four serotypes circu- lating simultaneously) and has a stable transmission pattern with periodic DHF/DSS epidemics occurring every 3-5 years. In these countries, DHF/DSS has become a frequent cause of hospitalization and death, with more than a million cases reported from 1986 through 1990 (17). In 1990, a resurgence of dengue fever/DHF began in Singapore -- despite a mosquito control program that had been successful since its initiation in 1968. During the 1980s, major epidemics occurred in both East and West Africa; and, although surveillance data for dengue and DHF in Africa are sparse, all four serotypes were documented on the continent. The increases in dengue activity in Africa, the Americas, and Asia represent a pandemic that is being facilitated by increased air travel; global urbanization; population growth; greater abundance of disposable, nondegradable containers that can serve as Aedes breeding sites; and lack of effective mosquito control (13,14). This report summarizes information about cases of dengue virus infection in the 50 United States and in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. METHODS Surveillance Procedures To evaluate dengue activity at national and international levels, CDC maintains several overlapping surveillance systems. Dengue surveillance in the 50 United States and the U.S. Virgin Islands relies on provider-initiated reports to the appropriate state or territorial health department. These health departments then submit serum samples and clinical information obtained from persons who have suspected cases of dengue to CDC for diagnostic confirmation. Additionally, other countries submit samples to CDC for diagnostic analysis or confirmation. Serum samples from suspected dengue cases are accompanied usually by a clinical summary; dates of onset of illness and blood collection; and epidemiologic information, including a detailed travel history with dates and location of travel. In Puerto Rico, CDC maintains an active laboratory-based surveillance program to provide early and precise information to public health officials regarding time and location of transmission, dengue virus serotype, and disease severity (18). CDC receives serum specimens from government clinics, public and private hospitals, and physicians' offices throughout Puerto Rico. These specimens are sent directly by physicians or collected locally and transported to CDC by staff of the Puerto Rico Department of Health. CDC also receives a copy of those death certificates filed in Puerto Rico that list dengue as a cause of death. A special system of surveillance for hospitalized dengue patients was started in 1984. As currently structured, this system relies on the assistance of hospital nurse epidemiologists (infection control practitioners), who provide detailed clinical information about hospitalized patients who have suspected cases of dengue. Community serosurveys are performed periodically at locations in Puerto Rico. Laboratory Methods Since 1984, serum specimens have been tested, using the IgM capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (MAC-ELISA), for anti-dengue IgM antibody to a mixture of four dengue virus antigens (19-21). Specimens with positive virus isolation or borderline results by MAC-ELISA were evaluated further with hemagglutination-inhibition (HI) testing (adapted to microtiter) (22) or, after October 1992, with an IgG-ELISA (23). Dengue viruses were identified with serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies in an indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test on either virus-infected C6/36 mosquito cell cultures or tissues from inoculated Toxorhynchites amboinensis or Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (24-26). Case Definitions A reported case of dengue was defined as an illness diagnosed as dengue by a health-care professional who subsequently notified the state or terri- torial health department. A probable case was defined as an illness that was clinically compatible with dengue in a person who had a positive IgM antibody test on a single late-acute- or convalescent-phase serum specimen, an HI titer greater than or equal to 1,280, or an equivalent IgG-ELISA antibody titer greater than or equal to 163,840. A confirmed case was defined as a probable case that met any of the following additional criteria for diagnosis: a) isolation of dengue virus from serum or autopsy tissue samples, b) a fourfold or greater change in IgG antibody titers in paired serum samples, or c) the demonstration of dengue virus antigen in autopsy tissue or serum samples by immunofluorescence or by viral nucleic acid detection (27). In this report, both probable and confirmed cases are considered laboratory-diagnosed cases. According to the World Health Organization, a case of DHF must fulfill the following criteria: fever, minor or major hemorrhagic manifestations, thrombocytopenia (less than or equal to 100,000/mm3), and objective evidence of increased capillary permeability (e.g., hemoconcentration {hematocrit increased by greater than or equal to 20%}, pleural effusion {by chest radiography or other imaging method}, or hypoalbuminemia). A case of DSS must meet all these criteria plus hypotension or narrow pulse pressure (less than or equal to 20 mm Hg) (28). RESULTS Dengue in Texas, 1986 In 1986, after several years of intense dengue transmission in Mexico, the first indigenous transmission of dengue in the United States in 6 years occurred in Texas (2,29). The previous indigenous transmission, which occurred in 1980 after an absence of 35 years, had also occurred in Texas (30). Five of the 14 CDC-confirmed cases reported from Texas during 1986 were probably imported; the remainder of these patients had not traveled outside the state, suggesting that the infections were acquired locally. Four cases were reported from Brownsville; three cases, Corpus Christi; and two cases, Laredo. A DEN-1 virus was isolated from one of these nine patients. Three (1%) blood samples from a random sample of 315 patients at sexually trans- mitted diseases clinics in southern Texas were positive for dengue-specific IgM antibodies, indicating dengue infection had been acquired within the 2-3 months preceding the serosurvey (2). No further evidence of endemic dengue transmission in Texas was reported through 1992. Imported Dengue in the United States, 1986-1992 From 1986 through 1992, CDC's Dengue Branch processed serum samples from 788 residents of 47 states (including Texas) and the District of Columbia to confirm clinical suspicion of dengue fever acquired during travel to tropical areas. Among the 788 residents, 157 (20%) dengue cases were diagnosed serologically or virologically (Table_1). Virus serotype was identified in 18 (11%) of these cases (seven cases of DEN-1; five, DEN-2; three, DEN-3; and three, DEN-4). Travel histories were available for 150 patients who had laboratory-diagnosed dengue. The majority (71 patients) had recently visited Latin America or the Caribbean, 63 had visited Asia and the Pacific, seven had visited Africa (including Madagascar), and nine had visited several continents. Travelers in the Americas acquired infections with DEN-1, DEN-2, or DEN-4, but all four serotypes were isolated from travelers to Asia and the Pacific. Persons with laboratory-diagnosed illness most commonly reported symptoms consistent with classic dengue fever (e.g., fever, rash, headache, and myalgia). At least 12 patients were hospitalized, and one patient died. U.S. Virgin Islands (St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John) A small outbreak of DEN-2 was documented in the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1986, with most cases reported from the island of St. John. The outbreak began in the latter part of 1986 and continued into 1987, when DEN-4 virus was also isolated. No hemorrhagic disease was reported (31). From the end of the outbreak through January 1989, a small number of laboratory-diagnosed cases occurred almost every month. Disease activity increased during August 1989 and peaked in November of that same year. At that time, the only case of DHF with laboratory-diagnosed dengue during 1986-1992 occurred in a 23-month- old child. During 1989, 275 serum samples were submitted for patients who had symptoms compatible with dengue. Dengue was diagnosed serologically or virologically in 124 (45%) of these patients. During 1990, 339 samples were submitted for patients who had symptoms compatible with dengue; of these, dengue was diagnosed serologically or virologically in 124 (37%). Confir- mation rates were similar to this overall rate for all three islands (St. Thomas, 107 {38%} of 285 cases; St. Croix, 12 {30%} of 40 cases; and St. John, five {36%} of 14 cases). That same year, low-level dengue activity was observed from March through August; a substantial increase in activity occurred during September, with incidence peaking 2 months later in November. During 1990, DEN-2 was the dominant serotype (i.e., 19 {86%} of the 22 isolates were DEN-2); in comparison, during the previous 2 years, 44 (76%) of the total 58 isolates were DEN-1. In 1989, DEN-1 activity was associated with the aftermath of Hurricane Hugo and transmission of the virus to disaster relief workers. In 1990, 21 isolates (DEN-2 and DEN-4 serotypes) were obtained from residents of St. Thomas; in 1989, only two isolates of DEN-2 were obtained from residents of this island. Only one isolate (DEN-1) was obtained in 1990 from St. Croix, compared with 18 DEN-1 viruses and one DEN-2 virus isolated in 1989. No isolates were obtained from St. John during 1989 and 1990. Of the 124 patients for whom dengue was diagnosed serologically or virologically during 1990 (i.e., 1.2 cases per 1,000 population), two patients (from St. Thomas) were hospitalized, and 13 (10%) had at least one mild hemorrhagic manifestation. No cases of severe hemorrhagic disease were reported from the U.S. Virgin Islands during 1990. Only 62 and 44 samples were submitted for laboratory testing from the U.S. Virgin Islands for 1991 and 1992, respectively; in comparison, an average of 302 samples were submitted annually for 1987-1990. Puerto Rico After the DEN-1 epidemic in 1981 and DEN-4 epidemic in 1982, Puerto Rico had a 3-year period with low-level, sporadic dengue transmission, averaging approximately 2,300 reported cases annually. In 1986, reported dengue cases increased to 10,659, with peak transmission occurring during September and October. Cases were confirmed in 71 (91%) of the island's 78 municipalities, and DEN-1, DEN-2, and DEN-4 viruses were isolated. This epidemic differed quantitatively and qualitatively from previous epidemics because of the cocirculation of multiple dengue virus serotypes and the concomitant increase in severity of the illness. Although one case of DHF with laboratory- diagnosed dengue occurred in 1975, the first deaths associated with laboratory-diagnosed dengue infection (n=3) and the first cluster of DHF cases (n=29) occurred in 1986 (13,15; CDC, unpublished data). Although the number of reported dengue cases subsequently decreased during 1987-1991, the annual levels were higher than those reported during the first half of the 1980s. Disease transmission in Puerto Rico followed a cyclical pattern, with increased incidence during months with higher temper- atures and humidity. In 1987, the peak reporting months were July and August; in 1988, April and November were both peak reporting months. From 1989 through 1992, peak reporting occurred from September through November. During 1986-1992, laboratory-diagnosed dengue cases occurred every month, and cases occurred in most of the island's municipalities. During this period, three virus serotypes (DEN-1, DEN-2, and DEN-4) circulated with varying frequency (Figure_5). A small number of laboratory-diagnosed DHF cases were reported every year (i.e., 17 cases in 1987; eight in 1988; 13 in 1989; six in 1990; and 14 in 1991). In 1991, the overall incidence of laboratory-diagnosed disease was 1.0 cases per 1,000 population. The highest incidence (1.3 cases per 1,000 population) occurred among persons 15-29 years of age; rates were similar for males and females. CONCLUSIONS The worldwide distribution of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes and the spread of dengue have caused 1,263,321 cases of DHF and 15,940 deaths during the 5-year period 1986-1990; in comparison, 715,238 cases of DHF and 21,345 deaths were reported during the 25-year period 1956-1980 (17). The recent increase in dengue incidence presents a risk both to travelers and to residents in areas of the United States where Ae. aegypti mosquito infestations occur (as demonstrated by the indigenous transmission in Texas during 1986). In the United States, imported cases of dengue are reported less frequently than are imported cases of malaria (i.e., approximately 1,200 imported cases of malaria are reported every year) (32). However, most dengue infections are minimally symptomatic, and probably only a few symptomatic patients submit serum samples for laboratory confirmation of dengue. Therefore, official reports of dengue incidence are probably underestimates of true incidence. Even though the number of laboratory-diagnosed dengue infections among travelers was small, severe and fatal disease was documented. The proliferation of mosquito breeding sites has surpassed the capacity of traditional mosquito control programs to inspect premises and apply insecticides. Because a vaccine is not currently available for dengue, CDC recommendations for dengue prevention emphasize sustainable, community-based mosquito control, with limited reliance on chemical larvicides and adulticides (33). The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has held regional meetings of member countries in Barbados, Brazil, Cuba, and Venezuela to discuss strategies for disease surveillance, vector control, emergency preparedness, and program evaluation. PAHO will soon publish the Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever in the Americas (34). Travelers to tropical areas can reduce their risk for acquiring dengue infection by taking precautions to avoid mosquito bites (i.e., using mosquito repellents, protective clothing, and spray insecticides). Ae. aegypti mosquitoes can be found near or inside houses, and they often rest in dark corners (e.g., inside closets and bathrooms, behind curtains, and under beds). The species bites preferentially (but not exclusively) in the early morning and the late afternoon (35). The risk for exposure may be lower for tourists in some settings, including beaches, hotels with well-kept grounds, and heavily forested areas and jungles. Physicians should consider dengue in the differential diagnosis of all patients who have symptoms compatible with dengue and who reside in or have visited tropical areas. When dengue is suspected, the patient's blood pressure, hematocrit, and platelet count should be monitored for evidence of hypotension, hemoconcentration, and thrombocytopenia. Acetaminophen products are recommended for management of fever to avoid the anticoagulant properties of acetylsalicylic acid (i.e., aspirin). Acute- and convalescent-phase serum samples should be obtained for viral isolation and serodiagnosis. Suspected dengue cases should be reported to the respective state or territorial health department; the report should include a clinical summary, dates of onset of illness and blood collection, and other epidemiologic information (e.g., a detailed travel history with dates and location of travel). Serum samples should be sent for confirmation through state health department laboratories to the Dengue Branch, Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC, 2 Calle Casia, San Juan, PR 00921-3200; telephone (809) 766-5181; FAX (809) 766-6596. The Dengue Branch publishes the Dengue Surveillance Summary on a quarterly basis. This publication is available free of charge to health professionals who are interested in the disease's distribution and manifes- tations and in community-based control programs. Copies can be obtained by contacting the Dengue Branch. References

Figure_1  Return to top. Figure_2  Return to top. Figure_3  Return to top. Figure_4  Return to top. Table_1 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size.

TABLE 1. Suspected and laboratory-diagnosed cases of imported dengue, by state --

United States, 1986-1992

=======================================================================================

No. cases

-------------------------

Laboratory-

State Suspected diagnosed Dengue serotype * (no. isolates)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alabama 35 3 --

Alaska 1 0 --

Arizona 2 0 --

Arkansas 18 0 --

California 26 11 (1) DEN-1, (1) DEN-3

Colorado 27 6 (1) DEN-3

Connecticut 12 2 --

Delaware 2 0 --

District of Columbia 15 9 --

Florida 23 4 (1) DEN-3

Georgia 35 8 (1) DEN-1

Hawaii 21 8 (1) DEN-2

Idaho 2 1 --

Illinois 24 7 (1) DEN-1

Indiana 6 2 --

Iowa 10 2 --

Kansas 7 2 --

Kentucky 30 0 --

Louisiana 1 0 --

Maine 3 1 --

Maryland 12 3 --

Massachusetts 72 20 (2) DEN-1

Michigan 25 6 (1) DEN-4

Minnesota 20 4 (1) DEN-1

Mississippi 5 0 --

Missouri 9 2 --

Montana 2 0 --

Nebraska 1 0 --

Nevada 1 0 --

New Hampshire 1 1 (1) DEN-2

New Jersey 13 2 --

New Mexico 7 0 --

New York 103 15 (1) DEN-2

North Carolina 9 2 --

North Dakota 2 0 --

Ohio 25 7 (1) DEN-2, (1) DEN-4

Oklahoma 3 0 --

Oregon 10 3 (1) DEN-4

Pennsylvania 13 4 --

Rhode Island 1 0 --

South Carolina 0 + 0 --

South Dakota 2 0 --

Tennessee 26 1 --

Texas 63 7 --

Utah 3 0 --

Vermont 5 2 --

Virginia 11 3 (1) DEN-2

Washington 26 7 (1) DEN-1

West Virginia 0 + 0 --

Wisconsin 18 2 --

Wyoming 0 + 0 --

TOTAL 788 157

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* If known.

+ Case reports not received during this period.

=======================================================================================

Return to top. Figure_5  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|