|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

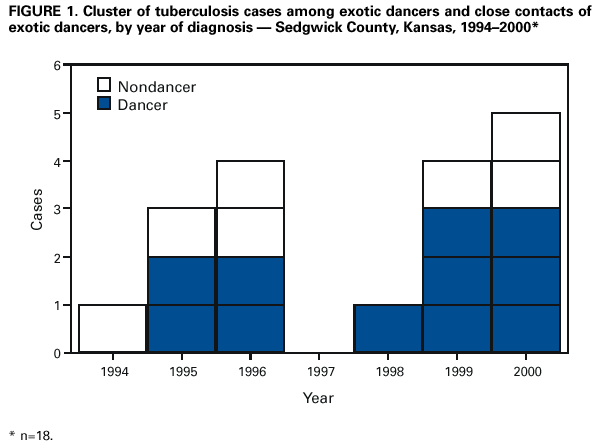

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Cluster of Tuberculosis Cases Among Exotic Dancers and Their Close Contacts --- Kansas, 1994--2000During January 2001, the Wichita-Sedgwick County Department of Community Health (WSCDCH), the Kansas Department of Health and Environment (KDHE), and CDC investigated a cluster of tuberculosis (TB) cases that occurred from 1994 to 2000 among women with a history of working as dancers in adult entertainment clubs (i.e., exotic dancers) and persons who were close contacts of exotic dancers. This report describes the results of the investigation and illustrates the need for early identification of TB clusters through ongoing surveillance and resources for health departments to respond rapidly to TB outbreaks. As of April 2001, the TB control staff of WSCDCH and KDHE had identified 18 TB cases in this cluster that had been diagnosed from 1994 to 2000 (Figure 1). Of these, 14 (78%) were culture confirmed; all Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates were susceptible to first-line anti-TB drugs. Eight patients were women (seven exotic dancers), seven were men, and three were children. Of the 15 adult patients, 14 were aged <45 years at the time of diagnosis. All dancers had cavitary pulmonary disease, an indication of increased infectiousness. All adult patients were voluntarily tested for human immunodeficiency virus infection and one was seropositive. Twelve (80%) of the 15 adult patients reported using cocaine, crack cocaine, or amphetamines, and 10 (67%) had been incarcerated at some time during 1994--2000. All 18 patients were started on directly observed therapy (DOT), and 17 completed treatment. Evidence linking these cases included common occupation or known exposure to exotic dancers. Of the 11 nondancer patients, six were exposed to dancers outside of the clubs exclusively. Although dancer patients identified six clubs in which they worked during their potential infectious periods, no single club could be confirmed as the site of transmission to all other dancers. Shared drug-related activities may have linked the adult patients; however, no specific location of drug use was identified (1). Of the nine M. tuberculosis isolates tested, all had matching IS6110 fingerprints, including isolates from six dancers (2). Contact investigations of the nine infectious TB patients identified 344 contacts. Of 302 contacts with a tuberculin skin test (TST) placed and read, 76 (25%) were TST positive. Among 243 contacts eligible for 10-to-12 week postexposure TST, 32 (13%) had follow-up TST placed and read. Of these, 14 (44%) had TST conversion indicating recent M. tuberculosis infection. Among 72 contacts eligible for latent TB infection (LTBI) therapy, 54 (75%) initiated therapy. Of the 54 contacts who should have completed therapy by January 2001, six (11%) had documented completion. Reported by: C Magruder, MD, R Woodruff, G Minns, MD, V Barnett, P Baker, E Brady, T Julian, MPH, Wichita-Sedgwick County Dept of Community Health; G Pezzino, MD, M Reece, A Alejos, Kansas Dept of Health and Environment. MD Cave, PhD, National Tuberculosis Genotype Surveillance Network, Little Rock, Arkansas. R Rothenberg, MD, Emory Univ School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Div of Applied Public Health Training; Statistics and Epidemiology Br, Div of Prevention Research and Analytic Methods, Epidemiology Program Office; Field Services Br and Surveillance and Epidemiology Br, Div of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB prevention; and EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate the need for local health departments to have sufficient resources for ongoing surveillance for TB and capacity to rapidly respond during a time of increased demand. The cluster in Kansas occurred over a 7-year period and encompassed 18 patients. The WSCDCH TB control staff consists of a full-time TB control nurse, a part-time physician consultant, and a full-time assistant. The nurse is primarily responsible for TB case management including DOT. In addition, in collaboration with the WSCDCH Health Surveillance Unit, the nurse is responsible for contact investigations and screening high-risk persons for TB with TST. Health departments in low incidence states such as Kansas (2.9* per 100,000 population during 2000) may have limited resources to respond to outbreaks while maintaining the essential components of TB control, thus hampering efforts to eliminate TB (3). Outbreaks of TB among persons who use illegal drugs and/or have been incarcerated can be difficult to investigate. Illegal drug users often belong to complex social networks, and members of these networks may be reluctant or unable to provide the names of their contacts to public health officials (4). Special techniques for exploring chains of transmission among members of complex social networks have been developed (5,6). In this cluster investigation, follow-up rates of 10-to-12 week postexposure TST and completion rates of LTBI therapy were low. New approaches beyond traditional methods of TB contact investigations are necessary to follow-up contacts discovered through social network analysis. These approaches must assure that all contacts are assessed for LTBI and that those with LTBI complete therapy. This may require DOT for LTBI in an outbreak to prevent further M. tuberculosis transmission. The findings in this report underscore that all states, including those with very low TB incidence, should maintain TB control capacity and have outbreak response plans that include methods to augment this capacity during unexpected increases in M. tuberculosis transmission (7). References

*Provisional 2000 data. Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 4/19/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/1/2001

|