|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

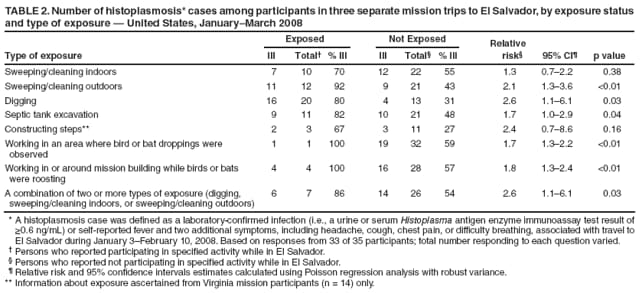

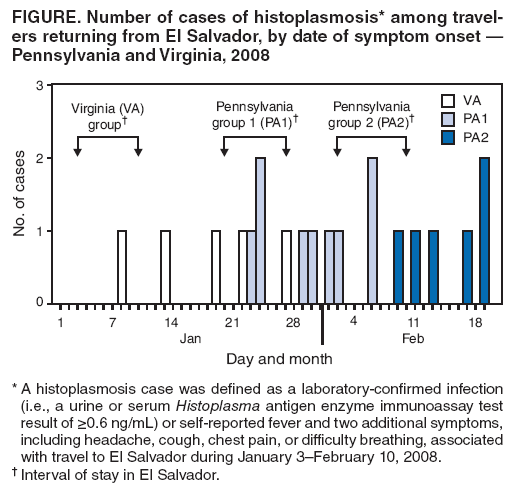

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Outbreak of Histoplasmosis Among Travelers Returning From El Salvador ---Pennsylvania and Virginia, 2008Histoplasmosis is a fungal disease caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum. Histoplasmosis, which can be acquired from soil contaminated with bird or bat droppings, occurs worldwide and is one of the most common pulmonary and systemic mycoses in the United States (1). However, among international travelers returning from areas in which histoplasmosis is endemic, histoplasmosis is rare, accounting for <0.5% of all diseases diagnosed in this group (1,2). During February--March 2008, the Pennsylvania and Virginia departments of health investigated a cluster of respiratory illness among three mission groups that had traveled separately to El Salvador to renovate a church. This report summarizes the results of the investigation. Of 33 travelers in the three mission groups for whom information was available, 20 (61%) met the case definition for histoplasmosis. Persons who reported sweeping and cleaning outdoors (relative risk [RR] = 2.1, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.3--3.6), digging (RR = 2.6, CI = 1.1--6.1), or working in a bird or bat roosting area (RR = 1.8, CI = 1.3--2.4) had a greater risk for illness. The findings emphasize the need for travelers and persons involved in construction activities to use personal protective equipment and decrease dust-generation when working in areas where histoplasmosis is endemic. Clinicians should consider histoplasmosis as a possible cause of acute respiratory or influenza-like illness in travelers returning from areas in which histoplasmosis is endemic. On February 13, 2008, the Pennsylvania Department of Health (PADOH) notified the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) of a cluster of nine persons with respiratory illness. The nine persons were among 11 members of a Pennsylvania-based mission group who had been renovating a church in Nueva San Salvador, El Salvador, during January 20--27, 2008. Two other mission groups, one from Virginia (16 members) and one from Pennsylvania (eight members), had traveled separately to assist with renovations of the same church during January 3--10, 2008 and February 2--10, 2008, respectively. After arrival, mission members immediately began renovation activities at the church. Renovation projects varied among the mission groups and included cleaning of indoor and outdoor renovation sites, electrical and plumbing installation, construction of additional rooms, roof replacement, and septic tank excavation. Mission members remained in El Salvador for the entire trip, but also visited local markets and churches and took a 1-day trip to either a beach or lake. The initial report from PADOH indicated that all nine persons from the initial cluster, upon returning from El Salvador, had presented to their health-care providers with respiratory symptoms. One of these persons was diagnosed with suspected histoplasmosis based on physical exam and a chest radiograph. To search for additional cases of illness among the mission groups, PADOH and VDH contacted the trip organizers and leaders. A case of histoplasmosis was defined as 1) a laboratory-confirmed H. capsulatum infection or 2) self-reported fever and two additional symptoms (i.e., headache, cough, chest pain, or difficulty breathing) beginning at least 24 hours after arrival in El Salvador, in any mission group member who traveled to El Salvador during January 3--February 10, 2008. Laboratory-confirmation was defined as either a urine or serum Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test result of >0.6 ng/mL. All participants from each mission group were administered a standard questionnaire through their church pastors or through telephone interviews. Information collected included demographics, illness, underlying health conditions, protective measures used, and potential exposures. Medical records of hospitalized patients also were reviewed, and a retrospective cohort study of the mission members was conducted. Statistical differences between proportions were assessed using chi-square and Fisher's exact tests of significance, when appropriate. Mean ages were compared using a t-test. Relative risk and 95% confidence interval estimates were calculated using Poisson regression analysis with robust variance. Information was collected from 33 (94%) of the 35 mission group participants. Twenty persons (12 males and eight females) met the case definition for histoplasmosis, for an overall attack rate of 61%. The 20 cases included histoplasmosis in five (36%) of 14 persons from the Virginia mission group, nine (82%) of 11 persons from the first Pennsylvania mission group, and six (75%) of eight persons from the second Pennsylvania mission group (Figure). Seven (35%) of the 20 ill persons met the case definition through laboratory-confirmed histoplasmosis based on urine specimens tested by EIA. The other 13 (65%) ill persons met the case definition through the symptom criteria, but eight of these 13 persons had urine specimens that tested negative by EIA. No participants had paired serologic antibody test results available. Median time from symptom onset to specimen collection date was 6 days (range: 1--28 days). Incubation periods could not be calculated because exact dates of exposure were not available; however, the median number of days between arriving in El Salvador and onset of symptoms was 12 (range: 3--25 days). Primary symptoms reported among the 20 ill persons meeting the case definition included fatigue (100%), fever or chills (95%), and headache (95%) (Table 1). Nineteen (95%) of the 20 ill persons visited a health-care provider, and six (30%) required hospitalization for their illness; all subsequently recovered. Because the clinical manifestation of histoplasmosis partly depends on the underlying health and immune status of the host, mission members were asked about their underlying medical conditions. Three ill persons reported a history of cancer, none reported a history of chronic lung disease, and none were current smokers. Differences in age (p=0.13), sex (p=0.44), and membership in mission group (p=0.06) were not statistically significant. Digging (RR = 2.6), sweeping or cleaning outdoors (RR = 2.1), and septic tank excavation (RR = 1.7) were associated with increased risk for illness (Table 2). For those persons who reported two or three high-risk exposures, defined as digging, sweeping indoors, or sweeping outdoors, the relative risk for illness was elevated (RR = 2.6), compared with those who reported no such high-risk exposures. In addition, those persons who worked in an area where bird or bat excrement was observed or where birds or bats were roosting had a higher attack rate than those who did not work in such areas. Sample size was not sufficient to stratify the analysis by mission group. None of the participants reported wearing a mask as personal protective equipment while working at the church site. Reported by: KA Warren, MPH, A Weltman, MD, Pennsylvania Dept of Health. C Hanks, T LaFountain, MSED, E Lowery, MPH, D Woolard, PhD, C Armstrong, MD, Virginia Dept of Health. AS Patel, PhD, KM Kurkjian, DVM, EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:H. capsulatum, the fungal causative agent of histoplasmosis, is endemic in the midwestern and central United States, Mexico, Central and South America, parts of eastern and southern Europe, parts of Africa, eastern Asia, and Australia (1). The fungus grows in the soil and its growth is thought to be enhanced by bird and bat excrement. Disruption of soil that contains bird or bat excrement is the primary means of aerosolization of and exposure to spores. Several reports have documented occupationally acquired outbreaks specifically associated with construction or renovation activities (4,5). However, persons not directly involved in the soil-disruption process, including travelers in the area, also are at increased risk because airborne spores can travel hundreds of feet (6). A histoplasmosis outbreak involving approximately 250 college students visiting a resort hotel in Mexico was associated with ongoing construction at the hotel (6). This is the first report of an outbreak of histoplasmosis among volunteer workers performing construction activities abroad. Evidence gathered during this investigation is consistent with previous research and revealed that performing outdoor activities, particularly those that cause soil disruption and spore aerosolization, increased the risk for acquiring histoplasmosis. Specifically, the two activities with the highest relative risk for illness were digging and sweeping outdoors. Histoplasmosis infections typically are asymptomatic or cause mild symptoms from which persons recover without antifungal or other treatment; persons with more severe forms of the infection (i.e., acute pulmonary, chronic pulmonary, and progressive disseminated histoplasmosis) are recommended for treatment with antifungal agents, such as amphotericin B (7). In this outbreak, the high overall attack rate among an otherwise healthy cohort, along with illness severe enough to require health-care services (including hospitalization), suggests substantial exposure to fungal spores during the renovation activities. In addition, working in an environment harboring bird or bat excrement likely increased the risk for acquiring histoplasmosis. Ultimately, the cause of this outbreak might be that the volunteers were not aware of the risk for histoplasmosis and therefore took no precautions, such as using personal protective equipment or taking care to decrease dust generation when working in this area of endemic disease. Although persons living or working in areas of endemic histoplasmosis might have previous health education and training about the risk and prevention of this disease, volunteers who travel to and work in these areas are likely to have limited, if any, training on disease risk and prevention. Multiple laboratory tests, including culture, histopathology, serology, and EIA antigen tests, can be used to diagnose histoplasmosis. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests depend on factors that include the patient's clinical syndrome, type and timing of specimen collection, fungal burden, and the host's immune status (8). In general, testing of convalescent serum samples offers the highest sensitivity for subacute and chronic pulmonary disease, and antigen testing (i.e., a quantitative, second-generation EIA), appears to be one of the most sensitive tests for acute pulmonary histoplasmosis (8). However, the EIA antigen test is less sensitive in milder infections when the fungal burden is lower (8,9). In this outbreak, five of seven patients with a positive urine EIA test required hospitalization. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, information about exposures and illness were ascertained via self-report, which might be associated with recall bias and subsequent exposure and disease misclassification. Second, misclassification of disease status is possible, given the negative antigen test results and given that infection with other respiratory pathogens (e.g., influenza virus) could not be ruled out for all ill persons. Finally, the majority of diagnostic specimens were tested by Histoplasma EIA only. Because EIA test sensitivity increases with increasing illness severity (8,9), specimens collected from persons with less severe disease might have tested falsely negative. Persons in areas of endemic histoplasmosis who perform certain jobs or activities, such as construction and farming, are at risk for acquiring histoplasmosis (10). Travel clinics and organizers of group travel to areas of endemic histoplasmosis should be informed about the risk for histoplasmosis among travelers with potential exposure to H. capsulatum. Clinicians should consider a diagnosis of histoplasmosis when evaluating a patient who has acute febrile respiratory illness and has traveled to an area in which histoplasmosis is endemic. Clinicians also should inquire about the patient's activities in the area of endemic disease. If histoplasmosis is suspected, consultation with laboratory experts is recommended to ensure the proper collection and referral of blood and urine specimens. Depending on the patient's clinical presentation, antigen testing for Histoplasma, convalescent serologic testing to detect antibodies, or culture might be performed to diagnose histoplasmosis. Travelers to areas of endemic histoplasmosis who visit caves or areas with high concentrations of bird or bat excrement, or who perform dust-generating activities, should consider using personal protective equipment (e.g., respirators) and dust-suppression strategies (e.g., keeping surfaces wet) to reduce their potential exposure to H. capsulatum. Acknowledgments The findings in this report are based, in part, on contributions by LJ Wheat, MD, MiraVista Diagnostics and MiraBella Technologies, Indianapolis; JF Howell, DVM, Indiana State Dept of Health; MT Temarantz, W Miller, DC, Pennsylvania Dept of Health; SE Whaley, DM Toney, PhD, M Bibbs Freeman, MS, Div of Consolidated Laboratory Svcs, Dept of General Svcs, Commonwealth of Virginia; BL Gomez, PhD, CM Scheel, PhD, R Miramontes, MPH, Mycotic Diseases Br, Div of Foodborne, Bacterial, and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases, CDC. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 12/17/2008 |

|||||||||

|