|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

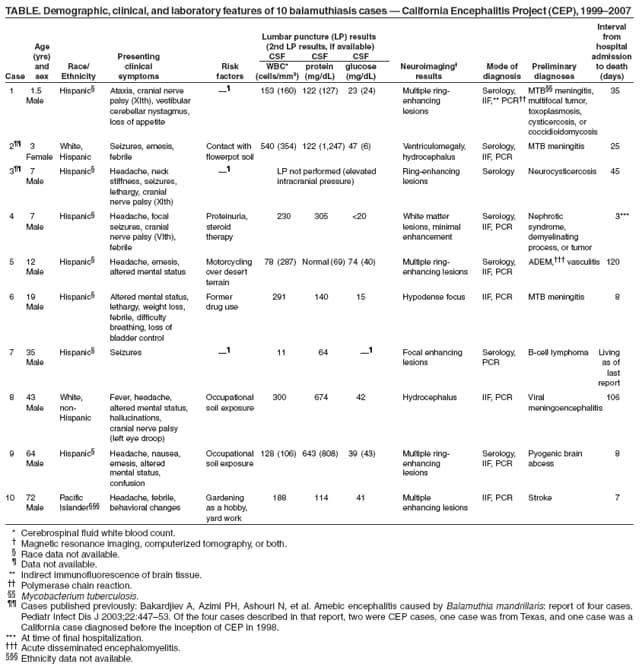

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Balamuthia Amebic Encephalitis --- California, 1999--2007Balamuthia mandrillaris is a free-living ameba that causes encephalitis in humans (both immunocompetent and immunocompromised), horses, dogs, sheep, and nonhuman primates. The ameba is present in soil and likely is transmitted by inhalation of airborne cysts or by direct contamination of a skin lesion. Approximately 150 cases of balamuthiasis have been reported worldwide since recognition of the disease in 1990 (1). Balamuthiasis is difficult to diagnose because 1) the clinical symptoms mimic those of several other types of encephalitis, 2) few laboratories perform appropriate diagnostic testing, and 3) many physicians are unaware of the disease. The lack of recognition and subsequent delay in diagnosis might be a factor in its high mortality. Since 1998, the California Encephalitis Project (CEP) has been testing encephalitis cases for both common and uncommon agents known to cause encephalitis, including Balamuthia. This report describes the 10 balamuthiasis cases identified by CEP during 1999--2007. The preliminary diagnoses in these cases included neurotuberculosis, viral meningoencephalitis, neurocysticercosis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. All but one patient died. These findings underscore the importance of increasing awareness among clinicians, epidemiologists, and public health officials for timely recognition and potential treatment of Balamuthia encephalitis. CEP SurveillanceCEP was initiated to better understand the etiologies, risk factors, and clinical features of human encephalitis. The project was started in 1998 in collaboration with the California Department of Public Health Viral and Rickettsial Disease Laboratory and CDC's Emerging Infections Program. Specimen referrals to CEP are received statewide from clinicians seeking diagnostic testing for immunocompetent patients aged >6 months who meet the CEP case definition for encephalitis. CEP defines encephalitis as illness in a patient hospitalized with encephalopathy and one or more of the following: fever, seizures, focal neurologic findings, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis, and electroencephalogram or neuroimaging results consistent with encephalitis. Specimens from approximately 3,000 encephalitis patients were referred to CEP during 1999--2007. The majority of submissions included acute serum (2,652), CSF (4,016), and respiratory samples (1,759). Five hundred cases were selected for Balamuthia serology based on at least one of the following: 1) clinical symptoms (e.g., cranial nerve palsies, seizures, and coma); 2) elevated CSF levels of protein and leukocytes, with normal or low glucose; 3) abnormal neuroimaging findings (e.g., hydrocephalus, ring-enhancing lesions, or space-occupying lesions); or 4) occupational or recreational contact with soil (e.g., work in agriculture or construction or dirt biking). A titer >1:128 was considered a presumptive positive and selected for further testing of brain tissue, if available. From the 500 patient specimens tested, 10 cases of Balamuthia encephalitis were identified, first by serology and then definitively by additional methods (Table). For two additional cases with elevated titers for Balamuthia antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) staining, brain tissue was not available, so the significance of positive titers is unknown. The median age of the 10 patients was 15.5 years (range: 1.5--72.0 years); nine of the patients were male. Seven of the 10 CEP cases occurred in southern California, and three occurred in central and northern California. Neurologic symptoms indicative of central nervous system (CNS) involvement were the initial manifestations in nine of the 10 cases. In one case, the patient developed a cutaneous lesion on his upper arm several months before development of CNS symptoms. Development of the lesion was temporally associated with cleaning a backyard pond. Postmortem, the skin lesion was found to be positive for Balamuthia amebae by indirect immunofluorescence staining and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and might have been the portal of entry preceding development of CNS disease. CSF analysis in nine of the 10 cases showed elevated protein with a median value of 188 mg/dL (range: 64--674 mg/dL), elevated white blood cell count with a median value of 170.5 cells/mm3 (range: 11--540 cells/mm3) and a lymphocytic predominance, and normal or low glucose with a median value of 40 mg/dL (range: 15--74 mg/dL). Abnormal neuroimaging results were observed in all 10 cases, headache was reported in six cases, altered mental status was reported in four cases, and manifestations of cranial nerve palsies were reported in four cases. The median interval from onset of symptoms to hospital admission was 8.5 days (range: 1--30 days) with a median hospital stay of 16.5 days (range: 3--120 days). Nine of the 10 balamuthiasis patients died; one was living at the time of last follow-up. Potential Risk FactorsFive patients had preexisting medical conditions: diabetes, gout and heart disease, status post splenectomy, nephrotic syndrome with a prolonged course on steroid therapy, and a possible lymphoma (Table). Patients in five of the 10 cases had a known exposure to soil: motorcycling in desert terrain, handling flowerpot soil, working in construction, or gardening as a hobby. No pertinent soil exposures were identified from the other five patients. Reported by: C Glaser, MD, DVM, F Schuster, PhD, S Yagi, PhD, S Gavali, MPH, Viral and Rickettsial Disease Laboratory, California Dept of Public Health; A Bollen, MD, Dept of Pathology, C Glastonbury, MD, Dept of Radiology, Univ of California Medical Center, San Francisco; R Raghavan, MD, D Michelson, MD, I Blomquist, MD, Loma Linda Children's Hospital, Loma Linda; D Scharnhorst, MD, Children's Hospital of Central California, Madera; S Kuriyama, MD, S Reed, MD, Univ of California Medical Center, San Diego; M Ginsberg, MD, San Diego County Health Dept, San Diego, California. G Visvesvara, PhD, P Wilkins, Div of Parasitic Diseases; L Anderson, MD, N Khetsuriani, MD, AL Fowlkes, Div of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Editorial Note:Balamuthia mandrillaris was first recognized and isolated from the brain of a pregnant mandrill baboon that had died in the San Diego Wild Animal Park in 1989 (2). The first human infections were reported in 1990, and in 1993, B. mandrillaris was described as a new genus and species of ameba (2,3). Since 1993, cases have been reported in western and central Europe, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, Mexico, Australia, Thailand, Japan, and India. Early reports of the disease in humans suggested that the infection occurred primarily in immunocompromised persons (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [HIV/AIDS] patients, injection-drug users, the elderly, and persons with concurrent health problems). However, many recent cases have occurred in immunocompetent children and adolescents (4). CEP detected its first case of Balamuthia encephalitis in 2001, 3 years after the inception of the project (5). Since 1990, a total of 15 known human cases with 12 deaths have been diagnosed in California (10 cases diagnosed by CEP and five cases where specimens were sent to CDC for diagnosis before the inception of CEP in 1998). Median age of the five patients whose specimens were sent to CDC was 16 years (range: 2--84 years); three of the patients were male. All but two of the 15 cases occurred in persons of Hispanic ethnicity, possibly because of environmental, genetic, or socioeconomic factors (6). Nearly 50% of cases in the United States have occurred in Hispanics (6). Because of the rarity of balamuthiasis, risk factors for the disease are not well defined. Two of five cases diagnosed by CDC occurred in patients who had exposure to soil. In addition to soil, stagnant water also might be a source of infection for balamuthiasis (7). Based on published case reports and positive laboratory detections at CDC and CEP, the disease appears to be more common in the southern tier of the United States (e.g., California, Texas, Georgia, and Florida), with fewer cases identified from states farther north (7). Similarly, most cases in California occurred in the southern part of the state. Currently, indirect immunofluorescence staining of formalin-fixed tissue specimens (e.g., brain tissue) is the definitive diagnostic test for balamuthiasis. Other tests include serologic testing (e.g., IFA), and recently, PCR, for identification of Balamuthia DNA in brain tissue or CSF (8). However, these tests are of an investigational nature and have not been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration. Four balamuthiasis survivors have been reported in the United States, including one described in this report. Long-term outcomes for these survivors varied. One patient, a California man aged 64 years, was described as performing all activities of daily living with good communication skills 5 years after his initial hospitalization (9). Another patient, a girl aged 5 years, had returned to school with moderate performance problems but with no gross neurologic sequelae 2 years after hospitalization (9). A third patient, a New York woman aged 72 years, was reported to have had no neurologic sequelae 6 months after hospitalization (10). These three surviving patients were treated with pentamidine isethionate, fluconazole, flucytosine (5-fluorocytosine), sulfadiazine, and a macrolide antibiotic (azithromycin or clarithromycin) (9,10). A fourth patient, a man aged 35 years, whose case was detected by CEP (Table), was still alive and in good condition 3 months after his diagnosis. However, specific information on his treatment regimen is unavailable; also, because he was lost to follow-up, his current status is unknown. Three additional balamuthiasis survivors have been reported in Peru (1); of these, one received no treatment, but the other two received prolonged therapy with albendazole and itraconazole (1). The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, brain tissue, either from biopsy or autopsy, is needed for unambiguous diagnosis of CNS balamuthiasis. Second, because the sensitivity and specificity of serology and PCR are unknown and brain tissue is likely to be available only from patients with advanced CNS disease, cases might have been missed. In particular, persons in an early stage of disease or those who had a less severe form of balamuthiasis would not have been included for further diagnostic testing, thus underestimating the burden of disease. In those cases, the opportunity for initiating therapy might have been missed. In the United States, two reference laboratories currently perform diagnostic testing for balamuthiasis, one at CDC and the other at the California Department of Public Health. Interested clinicians and laboratorians may seek testing for clinically consistent cases upon special request and prior approval (CDC contact: Govinda S. Visvesvara at e-mail gsv1@cdc.gov; CEP contact: Shilpa Gavali at e-mail shilpa.gavali@cdph.ca.gov). The confirmatory specimens for evaluation are paraffin-embedded, hematoxylin-eosin stained and unstained slides of affected brain tissue (available through biopsy or autopsy). Secondary diagnostic materials are 1) serum for Balamuthia antibody titer and 2) CSF and fresh or fixed brain tissue for PCR. The patient's medical history, including laboratory and neuroimaging results, also should be submitted. The full spectrum of clinical disease is unknown. Balamuthiasis should be considered in patients with unexplained encephalitis, especially those with lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated CSF protein (especially >100 mg/dL), and focal lesions on neuroimaging. Although only seven balamuthiasis survivors have been reported worldwide, early recognition of the infection might offer an opportunity to slow or stop progression of the disease (9,10). At present, the majority of cases are identified at autopsy. With improved diagnostic techniques, earlier therapeutic intervention might improve prognosis. Further studies are needed to estimate incidence, characterize risk factors, determine case-fatality rates, improve diagnostic methods, and evaluate the efficacy of therapeutic interventions. An important first step will be for public health personnel, clinicians, and pathologists to become knowledgeable about this disease. References

Table  Return to top.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 7/17/2008 |

|||||||||

|