|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

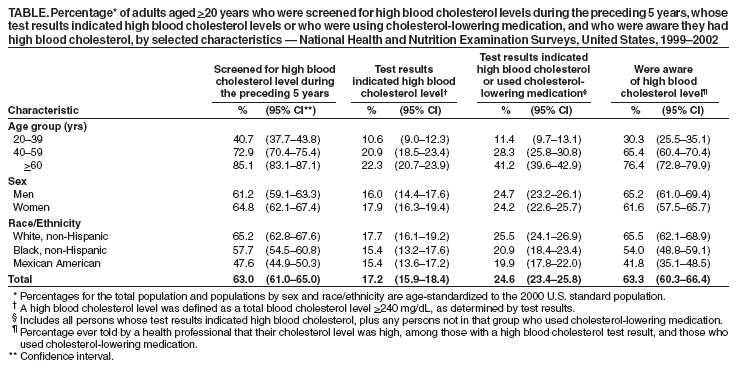

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Disparities in Screening for and Awareness of High Blood Cholesterol --- United States, 1999--2002High blood cholesterol is a major modifiable risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (1). Two national health objectives for 2010 are to reduce to 17% the proportion of adults with high total blood cholesterol levels and to increase to 80% the proportion of adults who had their blood cholesterol checked during the preceding 5 years (objectives 12-14 and 12-15) (2). In addition, an overall national health objective is to eliminate racial/ethnic and other disparities in all health outcomes (2). During 1960--1994, total blood cholesterol levels among the overall U.S. population declined; however, levels have changed little since then (3,4), despite increases in cholesterol screening and awareness (5). To assess racial/ethnic and other disparities among persons who were screened for high blood cholesterol during the preceding 5 years and among persons who were aware of their high blood cholesterol, CDC analyzed data from the 1999--2000 and 2001--2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES). This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicated that Mexican Americans, blacks, and younger adults were less likely to be screened for high blood cholesterol, and persons in those populations who had high cholesterol were less likely to be aware of their condition. Efforts are needed to encourage persons, especially among these populations, to seek screening and gain awareness of high blood cholesterol. The 1999--2000 and 2001--2002 NHANES conducted by CDC were designed to be nationally representative of the noninstitutionalized, U.S. civilian population on the basis of a complex, multistage probability sample. Persons with low incomes, persons aged >60 years, blacks, and Mexican Americans were oversampled. For this analysis, data from the two surveys were aggregated to increase sample size. For this report, only participants classified as Mexican American, non-Hispanic white, or non-Hispanic black were included. All persons in this report referred to as white or black are non-Hispanic; Mexican Americans might be of any race. Interviews were conducted both in English and Spanish. For 1999--2002, the examined response rate among persons in the sample was 78.1%. Data were collected from 8,112 survey participants aged >20 years who were interviewed in their homes and subsequently provided blood samples for cholesterol level determination in mobile examination centers. Participants were considered to have high blood cholesterol if 1) testing indicated their total cholesterol level was >240 mg/dL or 2) they reported currently taking cholesterol-lowering medication, regardless of their test result. Subjects were asked whether they had their blood cholesterol checked during the preceding 5 years and whether they had ever been told by a health professional that they had high blood cholesterol. Estimated population numbers, prevalences, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by using statistical analysis software to account for nonresponse and complex sampling design. The percentages of persons in various populations with high cholesterol levels or who had undergone blood cholesterol screening were age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard population (6). Odds ratios (ORs) and CIs were obtained by using logistic regression models that included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. All results in this report are statistically significant (p<0.05) unless otherwise indicated. During 1999--2002, the overall age-adjusted prevalence of cholesterol screening was 63.0%, corresponding to approximately 106 million (CI = 102 million--109 million) persons in the United States. Disparities in cholesterol screening were observed by age, sex, and race/ethnicity (Table). The likelihood of having had blood cholesterol screening within the preceding 5 years increased with age. Women were more likely than men (adjusted OR [AOR] = 1.20; CI = 1.03--1.39) to have had their cholesterol checked during the preceding 5 years. Blacks were less likely than whites (AOR = 0.70; CI = 0.57--0.84) and Mexican Americans were less likely than whites (AOR = 0.43; CI = 0.35--0.53) to have had their cholesterol checked during the preceding 5 years. The percentage of U.S. adults with high blood cholesterol levels increased with age (Table). On the basis of test results only, the age-adjusted prevalence of high blood cholesterol levels overall was 17.2%, which corresponds to approximately 29 million (CI = 27 million--31 million) persons in the United States. On the basis of either test results or use of

cholesterol-lowering medication, the overall prevalance of high blood cholesterol was 24.6%, which corresponds to approximately 41 million (CI

= 39 million--43 million) persons. Prevalence of measured high blood cholesterol or use of

cholesterol-lowering medication was lower among blacks (AOR = 0.74; CI = 0.60--0.91) and Mexican Americans, respectively, when compared with whites (AOR = 0.70; CI = 0.59--0.84), after adjustment for age and

sex. Overall, 63.3% of participants whose test results indicated high blood cholesterol or who were on a cholesterol-lowering medication had been told by a health professional they had high cholesterol before the survey. The likelihood of this awareness increased with age. Women were less likely than men (AOR = 0.68; CI = 0.50--0.91) to be aware of their condition. Blacks were less likely than whites (AOR = 0.67; CI = 0.51--0.89), and Mexican Americans were less likely than whites (AOR = 0.47; CI = 0.33--0.67) to be aware of their condition; less than half (42%) of Mexican Americans with high cholesterol were aware of their condition. Reported by: AZ Fan, MD, KJ Greenlund, PhD, S Dai, MD, JB Croft, PhD, Div of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:This analysis indicates that, in 1999--2002 the proportions of blacks and Mexican Americans who had been screened for high blood cholesterol during the preceding 5 years was lower than the proportion for whites. The proportions of blacks and Mexican Americans with high blood cholesterol who had been told by a health professional of their condition also was lower than the proportion for whites. In addition, younger adults were less likely than older persons to be screened for and aware of their high cholesterol condition. Although women participants were more likely than men to have had their cholesterol checked during the preceding 5 years, those women whose test results indicated high cholesterol or who were on cholesterol-lowering medication were less likely than men to be aware of their high cholesterol condition. A previous study determined that women were only half as likely as men to have their total blood cholesterol controlled at <200 mg/dL, the level considered desirable (4). Participants in the study described in this report were defined as having high cholesterol if they had a measured total blood cholesterol level >240 mg/dL or reported taking cholesterol-lowering medication; this combination resulted in a higher prevalence estimate (24.6%) than the measured results alone (17.2%). NHANES data have previously indicated that the prevalence of high blood cholesterol levels among U.S. adults aged 20--74 years, as determined by testing only, decreased from 27.8% during 1976--1980 to 19.7% during 1988--1994 (3). The prevalence for the same age range obtained from NHANES 1999--2002 was 17.4%; however, the mean serum total cholesterol of U.S. adults has changed little since the 1988--1994 survey (4). The decreasing prevalence of high blood cholesterol as measured by laboratory tests likely reflects increased use of cholesterol-lowering medication. Persons who have lowered their cholesterol by using medication might have other cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., high blood pressure) that place them at higher risk than persons with naturally lower cholesterol levels (7). Determining the prevalence of high blood cholesterol by accounting for persons using cholesterol-lowering medication, in addition to testing, might provide a more complete estimate of the health burden related to high blood cholesterol. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, data were only collected from persons in the noninstitutionalized population; persons residing in nursing homes or other institutions were not included. Second, only non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans were oversampled in NHANES 1999--2002; consequently, estimates could not be calculated for other minority populations (e.g., Asians, Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and other Hispanic subpopulations). The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) recommends that all adults aged >20 years have their cholesterol checked at least every 5 years (8). The data in this analysis indicated that approximately 63% of U.S. adults had their cholesterol checked during the preceding 5 years, below the national health objective of 80% for 2010. Public health campaigns to raise awareness of the cardiovascular disease risk associated with high blood cholesterol levels should focus particularly on blacks, Mexican Americans, younger adults, and women. Ongoing campaigns conducted by the American College of Cardiology; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and American Heart Association are aimed at raising awareness of this risk among women (9). NCEP provides guidelines on therapeutic lifestyle changes in nutrition, physical activity, weight control, and drug therapy, to achieve desirable cholesterol levels (8). Physician adherence to guidelines that emphasize more intensive cholesterol-lowering treatment for patients at higher cardiovascular risk can also help lower the U.S. health burden related to high blood cholesterol (10). References

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 2/10/2005 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 2/10/2005

|