|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

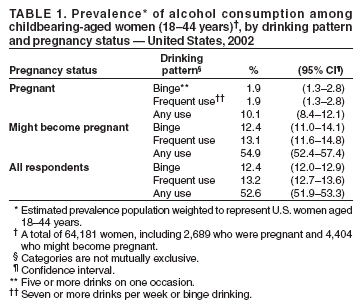

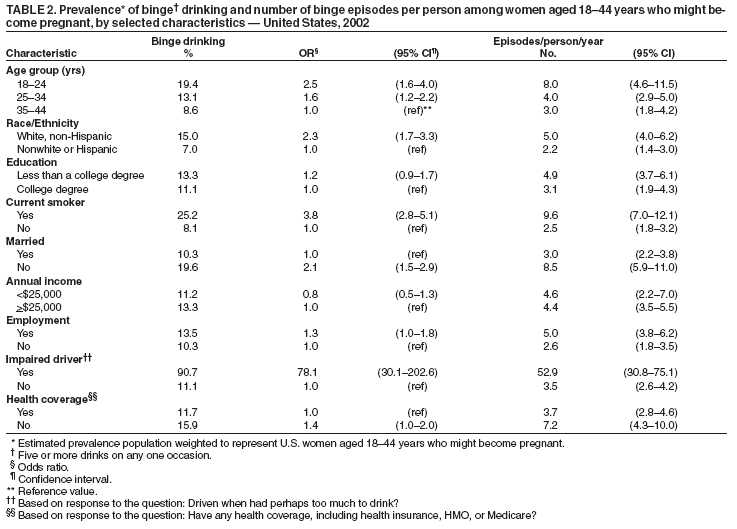

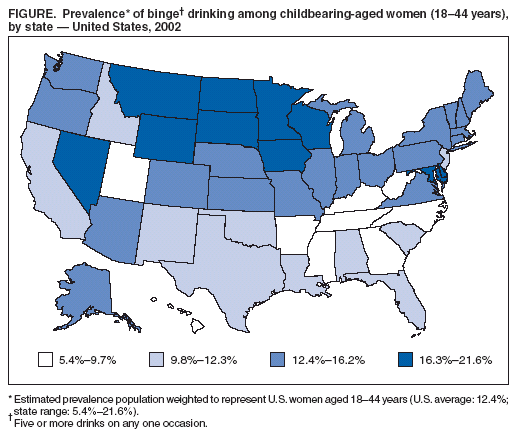

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Alcohol Consumption Among Women Who Are Pregnant or Who Might Become Pregnant --- United States, 2002Alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with health problems that adversely affect the mother and fetus (1,2); no level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy has been determined safe (3). Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is recognized as the foremost preventable condition involving neurobehavioral and developmental abnormalities (1). Women who drink during pregnancy place themselves at risk for having a child with FAS or fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) (4). To determine the alcohol consumption patterns among all women of childbearing age, including those who are pregnant or might become pregnant, CDC analyzed data for women aged 18--44 years from the 2002 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey (5). The results of that analysis indicated that approximately 10% of pregnant women used alcohol, and approximately 2% engaged in binge drinking or frequent use of alcohol. The results further indicated that more than half of women who did not use birth control (and therefore might become pregnant) reported alcohol use and 12.4% reported binge drinking. Women who are pregnant or who might become pregnant should abstain from alcohol use (3). CDC monitors the prevalence of alcohol use among women of childbearing age through BRFSS. In 2002, with the inclusion of a family planning module in the BRFSS survey, information became available to assess the alcohol consumption patterns among pregnant women and also among women who might become pregnant. BRFSS is a monthly, state-based, random-digit--dialed telephone survey of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged >18 years in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and three U.S. territories (5). In 2002, the median state/area response rate was 58.3% (range: 42.2%--82.6%). For 2002, a total of 64,181 women aged 18--44 years were included as the general population of childbearing-aged women. Participants were asked about their use of alcohol during the 30 days preceding the interview. Alcohol usage questions included the number of days per week or month the respondents had at least one drink, the average number of drinks consumed on a drinking day, the number of times the respondents had five or more drinks per occasion, and the number of times they drove when they had "perhaps too much to drink." The following alcohol consumption patterns were assessed: any use (at least one drink on one occasion), binge drinking (five or more drinks on one occasion), and frequent drinking (seven or more drinks in a week or binge drinking). In addition, women were asked whether they or their partners were doing anything to prevent pregnancy. Reasons were collected from women who responded that they or their sex partners were not doing anything to prevent pregnancy. For this analysis, 4,404 women who might become pregnant were defined as those who were not using any type of birth control and provided one of the following reasons: wanted a pregnancy (52.4%), did not care whether pregnancy occurred (19.1%), did not think they would become pregnant (14.3%), did not want to use birth control (5.7%), feared the side effects of birth control (4.2%), thought they were too old to become pregnant (1.8%), could not pay for birth control (1.3%), or had lapsed in use of a method (1.2%). Excluded from this defined category were women who were not sexually active, had a same-sex partner, had no sex partner, had undergone sterilization or hysterectomy, were postpartum breastfeeding, were currently pregnant, had other unspecified reasons for not using birth control, or did not provide any reason. Prevalences for alcohol consumption patterns were calculated for women who were pregnant, those who might become pregnant, and women of childbearing age overall. A total of 2,689 women reported that they were pregnant. Because of the limited number of pregnant women available in the 2002 BRFSS sample population, additional analyses were performed by focusing only on the demographic characteristics of women who might become pregnant and who engaged in binge drinking. To obtain appropriate statistics, weighted data analyses were performed to reflect general population estimates (6), and standard errors were calculated by using statistical analysis software. The 2,689 women who reported that they were pregnant and the 4,404 women who might become pregnant represented population-weighted estimates of 4.7% and 7.6%, respectively. Among those who reported not using birth control, 52.4% said that they wanted to become pregnant. The prevalence of binge drinking was 12.4%, both for childbearing-aged women overall and for those who might become pregnant, and 1.9% for pregnant women (Table 1). The prevalence of frequent drinking was 13.2% for childbearing-aged women overall, 13.1% for women who might become pregnant, and 1.9% for pregnant women. The prevalence of any use of alcohol was 52.6% for the childbearing-aged population overall, 54.9% for women who might become pregnant, and 10.1% for pregnant women (Table 1). Binge drinking prevalences for childbearing-aged women overall varied among participating states, ranging from 21.6% in Wisconsin (95% confidence interval [CI] = 18.8%--24.8%) to 5.4% in Kentucky (CI = 3.8%--7.5%) (Figure). To generate odds ratios for the risk of binge drinking among women with selected characteristics, additional analyses using logistic regression were conducted for women who might become pregnant (Table 2). Greater binge-drinking prevalence was observed among younger women, non-Hispanic whites, current smokers, unmarried women, and impaired drivers. These populations also reported more binge-drinking episodes per person per year than did their reference populations (Table 2). Reported by: J Tsai, MD, RL Floyd, DSN, Div of Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC. Editorial Note:The 2002 BRFSS survey provided an opportunity to monitor alcohol consumption among women of childbearing age, including those who were pregnant and, for the first time at the national level, those who might become pregnant. The results of this analysis indicated that the prevalences of alcohol use among women who might become pregnant were similar to those for childbearing-aged women overall. In addition, the prevalences for childbearing-aged women overall and those who were pregnant were similar to those reported previously (7). The findings indicated that more than half of women who might become pregnant reported drinking alcohol, including 12.4% who reported binge drinking and, therefore, were at particular risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy (8). A dose-response relation has been observed between prenatal alcohol consumption and dysmorphic brain development in the fetus as early as 3--6 weeks' gestation (2), a period during which the majority of women might not know they are pregnant. Further studies have determined that alcohol consumption can be associated with prenatal growth delays and neurodevelopmental insults throughout the entire pregnancy (8). The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, because data were self-reported, they are subject to recall bias (5). Second, only women who reported they were not using birth control were counted as women who might become pregnant. Women using ineffective birth control methods were not included, although they might become pregnant because of improper usage or failure of a method. These findings signal the need for continued efforts to inform all women of childbearing age about the adverse effects of alcohol on pregnancy, and to identify and intervene with those women at higher risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancy (9). Providing primary-care screening of childbearing-aged women for alcohol use and risk for pregnancy and initiating intervention when appropriate is essential for prevention of FAS or FASD (10). References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 12/22/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 12/22/2004

|