|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

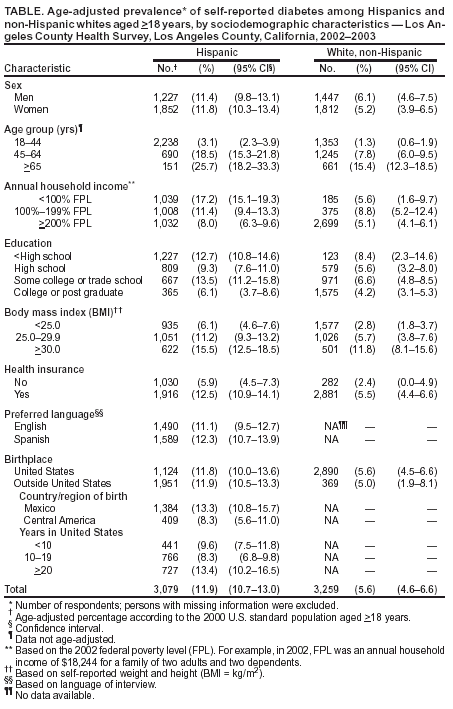

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Diabetes Among Hispanics --- Los Angeles County, California, 2002--2003Diabetes is associated with severe morbidity and premature death and affects U.S. Hispanics disproportionately (1). Although regional variation in diabetes prevalence has been observed among Hispanics (2), limited information is available on how sociodemographic factors affect the risk for diabetes among Hispanics in urban settings. Los Angeles County (LAC), California, has the largest urban Hispanic population in the United States (3). To assess the prevalence of diabetes among Hispanic adults in LAC and to examine variations in diabetes prevalence across sociodemographic groups in this population, the LAC Department of Health Services analyzed data from the 2002--2003 LAC Health Survey (LACHS). This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicate that the prevalence of diabetes is approximately two times higher among Hispanics than among non-Hispanic whites and is strongly associated with living below poverty level*. These findings underscore the need to provide additional diabetes prevention and treatment interventions for Hispanics in LAC, particularly those living in poverty. LACHS is a periodic, random-digit--dialed telephone survey of the noninstitutionalized population in LAC (4). Adults aged >18 years were surveyed during October 2002--February 2003. Interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, and four Asian languages. Of 15,262 households contacted, 8,167 interviews were completed (response rate: 53.5%). Respondents were considered to have diabetes if they answered "yes" to the question, "Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had diabetes?" Women who reported having had diabetes only during pregnancy were classified as not having diabetes. Data were weighted to reflect the age, sex, and racial/ethnic distribution of the county population on the basis of 2002 projections from U.S. Census Bureau data. The prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites was assessed by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, annual household income level, education level, country of birth, health insurance coverage, and body mass index (BMI) from respondents' self-reported weight and height (BMI = kg/m2). Persons were classified as overweight if their BMI was 25.0--29.9 and obese if their BMI was >30.0. Black, Asian, and other populations were not included in the analysis because of insufficient sample size. Among non-U.S.--born Hispanics, diabetes prevalence also was assessed by the number of years lived in the United States and preferred language (i.e., English versus Spanish, with preference determined by the language used for the interview). Results were age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population; the Mantel-Haenszel chi square test was used to assess whether differences in diabetes prevalence among population groups were statistically significant. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the independent association between income and diabetes prevalence among Hispanics after controlling for age, health insurance status, and BMI. During 2002--2003, the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics was approximately two times higher than among non-Hispanic whites (11.9% versus 5.6%; p<0.01) (Table). Among members of both populations, the prevalence of diabetes increased with age. Diabetes prevalence was highest among Hispanics with annual household incomes below federal poverty level (FPL) (17.2%) and those who were obese (15.5%). Lower income levels were significantly associated with a higher prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics (p<0.01, chi square test for trend) but not among non-Hispanic whites, whereas lower levels of education were associated with higher prevalence of diabetes among both Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites (p = 0.02, chi square test for trend). The prevalence of diabetes was similar among both Spanish- and English-speaking Hispanics (12.3% versus 11.1%) and among both U.S.- and non-U.S.--born Hispanics (11.8% versus 11.9%). Among non-U.S.--born Hispanics, the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes was significantly higher among those born in Mexico than among those born in Central America (13.3% versus 8.3%; p<0.01) and among those who had lived in the United States for >20 years than among those who did so for <20 years (13.4% versus 9.4%; p<0.01). Hispanics living in poverty were approximately three times more likely (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.9; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.0--4.3) to have diabetes than were Hispanics with incomes of >200% FPL (e.g., incomes of >$36,488 for a family of two adults and two dependents) after controlling for age and health insurance coverage. This difference remained significant even after controlling for BMI (AOR = 2.7; 95% CI = 1.8--4.0). Reported by: PA Simon, MD, Z Zeng, MD, CM Wold, MPH, JE Fielding, MD, Los Angeles County Dept of Health Svcs, Los Angeles, California. NR Burrows, MPH, MM Engelgau, MD, Div of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:Consistent with national studies (2), the findings in this report indicate that the prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics is approximately two times higher than among non-Hispanic whites. Among Hispanics in LAC, the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes varied substantially across population subgroups. Poverty was one factor associated with the prevalence of diabetes. The factors contributing to this association remain unclear but could reflect an increased risk for diabetes among those living in poverty or a decline in income after a diabetes diagnosis. Although overweight and obesity are important contributors to racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of diabetes (5), the association between poverty and diabetes in this survey was largely independent of BMI. Physical inactivity and dietary factors independent of overweight and obesity also could explain the association but were not assessed in the study. The prevalence of diabetes among U.S.-born Hispanics in LAC was similar to that among non-U.S.--born Hispanics, and the prevalence among English-speaking Hispanics was similar to that among Spanish-speaking Hispanics. However, among non-U.S.--born Hispanics, diabetes prevalence was highest among those who had lived in the United States for >20 years, suggesting a potential acculturation effect unrelated to language. In addition, the higher prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics born in Mexico than among those born in Central American countries highlights the heterogeneity of the Hispanic population and might indicate different risk profiles for developing diabetes. The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, because households without telephones were excluded from the sampling frame, the results do not include a segment of the population that might be at increased risk for diabetes (6). Second, prevalence estimates based on self-reports do not account for adults with undiagnosed diabetes, a group estimated to constitute approximately one third of the total U.S. adult population with diabetes (7). Third, the lower prevalence of diagnosed diabetes among those without health insurance coverage suggests that barriers to health care might have influenced the results. Although health insurance status was controlled for in the multivariate analysis, other barriers to health are might have introduced bias. Finally, the response rate was 53.5%; however, the sociodemographic distribution of respondents was similar to that of the adult population in LAC. Increases in the national prevalence of both diabetes and obesity (8) underscore the need for additional national and state programs and community-level interventions to address these public health threats. In April 2003, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced the Steps to a HealthierUS initiative to support evidence-based and community-focused prevention programs for diabetes, obesity, and asthma. In LAC, efforts are under way to expand diabetes prevention and control efforts within low-income Hispanic and black communities, including campaigns to promote physical activity (e.g., Fuel Up/Lift Off! LA and Adopt-A-Park campaigns), interventions to improve nutrition (e.g., Project LEAN and the 5-a-Day campaigns), and community outreach to increase access to health-care services among persons with or at risk for diabetes. Ongoing population-based tracking of diabetes prevalence and diabetes-related morbidity in LAC will be essential for assessing the effectiveness of these efforts and for guiding future program planning. References

* Based on the 2002 federal poverty level (FPL), which takes into account both income and household size. For example, in 2002, FPL was an annual household income of $18,244 for a family of two adults and two dependents.

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 11/26/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 11/26/2003

|