|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

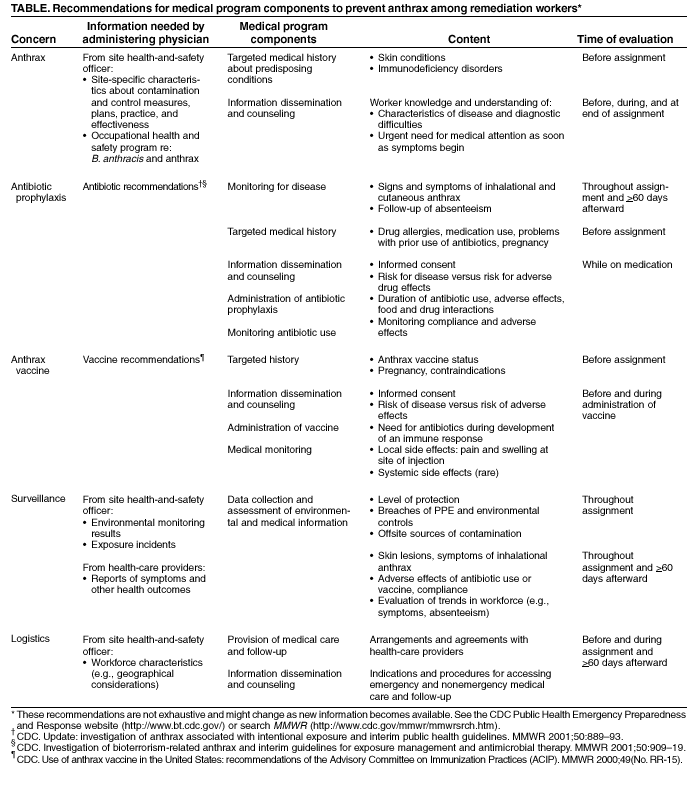

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Notice to Readers: Occupational Health Guidelines for Remediation Workers at Bacillus anthracis-Contaminated Sites --- United States, 2001--2002Remediation workers involved in clean up and decontamination are potentially exposed to Bacillus anthracis spores while working in contaminated buildings along the paths of letters implicated in bioterrorism-related anthrax. Federal guidelines and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations for hazardous waste operations and hazardous material response workers (HAZWOPER) (1,2) provide information about surveillance for hazardous exposures, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and clothing, and a generic medical program but do not address anthrax specifically. CDC has developed the following guidelines to provide medical protection for current and future workers responsible for making B. anthracis-contaminated buildings safe for others to enter and occupy. This information will benefit medical directors and consultants who design and supervise medical components of the OSHA-required health and safety plan (HASP), health-care providers who implement these programs for onsite workers or who care for workers offsite, and site health and safety officers who coordinate onsite programs. HAZWOPER Guidelines and RegulationsA medical program for remediation workers should be part of a site-specific HASP that also includes 1) environmental surveillance of health hazards; 2) engineering and administrative controls and use of PPE; 3) training about exposures, potential adverse health events, and preventive measures; and 4) an emergency response plan (1,2). The medical program should be designed and administered by a licensed physician in conjunction with the site health and safety officer. The administering physician should be knowledgeable about all of the relevant areas of occupational medicine (e.g., toxicology, industrial hygiene, medical screening, and occupational health surveillance) (3) and should be able to interpret information about potential exposures, PPE, work schedules, work practices, and relevant regulations. Because work sites might be remote from the home base, health-care providers implementing the program should be selected for accessibility to workers, access to diagnostic resources and a reliable system for hospital referral, and the ability to conduct around-the-clock coverage for work-related medical care. Baseline medical evaluations should identify pre-existing conditions affecting a worker's fitness for duty, ability to use PPE safely, and susceptibility to adverse work-related health outcomes. Periodic evaluations should be scheduled to detect symptoms and signs related to workplace exposures and to reassess fitness for duty. Active surveillance for exposure incidents (e.g., PPE breaches) and adverse health outcomes should determine the need for additional evaluations. Exit evaluations should identify changes from the person's baseline and any new risk factors. Selection of specific PPE should be based on an assessment of potential exposures and activities; the highest level of protection (i.e., level A) might be required (4). Examining physicians should be familiar with the physical requirements and limitations imposed on workers by the selected PPE (e.g., water-impermeable, chemical-resistant suits prevent evaporative cooling and contribute to dehydration and heat stress; facepieces might aggravate claustrophobia; respirator air-flow resistance and the weight of self-contained breathing apparatuses [SCBAs] might aggravate respiratory and heart conditions; and PPE materials might contribute to skin problems). When notifying the employer of a worker's fitness for duty, health-care providers should maintain confidentiality of medical information according to ethical and legal requirements. Workers should be notified of the results of their own evaluations. Medical Measures to Prevent AnthraxDespite the use of PPE, remediation workers are at risk for exposure to B. anthracis spores because spores might be reaerosolized (R. E. McCleer, CDC, personal communication, 2002), PPE is not 100% protective (5), individual work practices might lead to exposure (5), breaches in PPE and environmental controls might occur, and some breaches might go unrecognized. Neither the infective dose for development of inhalational anthrax nor the level of exposure to B. anthracis during remediation activities has been characterized adequately. Because of these uncertainties and because anthrax is potentially fatal, workers entering B. anthracis-contaminated sites should be vaccinated adequately with anthrax vaccine or protected with antibiotic prophylaxis. This recommendation also applies to workers entering areas that already have been remediated but have not yet been cleared for general occupancy. The use of medical measures for preventing anthrax does not eliminate requirements for use of PPE when entering uncleared areas. The initial medical evaluation should screen for contraindications to anthrax vaccine or antibiotic use, and periodic evaluations should monitor for adverse effects (Table). Workers should be educated about possible adverse effects and antibiotic interactions with food and drugs. To prevent anthrax, CDC has recommended 60 days of antibiotic prophylaxis after exposure to B. anthracis (6). Unvaccinated remediation workers should begin antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of their first entry and continue until at least 60 days after last entry into a contaminated area. Remediation workers with repeated entries into contaminated sites over a prolonged period of time require antibiotic coverage for considerably longer than the 60 days recommended for persons with a one-time exposure. Some remediation workers have been treated with antibiotics for >6 months, and remediation projects are not yet complete. Prolonged antibiotic use might cause side effects (frequently mild but occasionally severe) and might also result in the development of resistant microorganisms. Although supplies for civilian use remain severely limited, CDC recommends anthrax vaccine adsorbed (BioThrax™, formerly known as AVA, BioPort Inc, Lansing, Michigan) for workers who will be making repeated entries into known contaminated areas and is making BioThrax™ available to workers meeting these criteria. This ultimately will reduce the need for antibiotic prophylaxis and associated side effects for vaccinated persons. The recommended pre-exposure course of BioThrax™ is 6 doses (at 0, 2, and 4 weeks and at 6, 12, and 18 months) with annual boosters (7). If BioThrax™ is administered while the risk for exposure continues, CDC recommends concomitant antibiotic prophylaxis throughout the period of risk for exposure and for 60 days after the risk for exposure has ended unless the 6-dose initial series has been completed and annual boosters are up to date. Anthrax-Related Medical Monitoring and Follow-upNo validated methods exist for monitoring a person's exposure to B. anthracis. Nasal swabs and serology might be useful as epidemiologic tools but are not appropriate for medical surveillance of potentially exposed individual workers. Results of these tests should not be used to assess individual exposure or to make decisions about antibiotic prophylaxis (8). Inhalational exposure to a high dose of B. anthracis spores might result in rapid death. Therefore, in the absence of PPE, exposure to aerosolized powder known or strongly suspected to be contaminated with B. anthracis spores should be treated as a medical emergency (i.e., requiring prompt initiation of antibiotic prophylaxis). Fully vaccinated workers wearing appropriate PPE would not require antibiotic prophylaxis unless they had a breach in their PPE that allowed inhalation of ambient air, for example, a disruption of their respiratory protection. All workers should be trained to recognize and report exposure incidents and early symptoms and signs of anthrax, understand the importance of immediate medical attention, and know how to access emergency medical care. Medical follow-up should be provided as long as the risk for anthrax exists, whether the worker is onsite, off duty (including vacation or holiday), or no longer working at the remediation site. Because remediation work is transient and the workforce highly mobile, special arrangements are necessary for following workers after they leave the worksite. SummaryDespite the apparently low disease rate from exposure, protection for remediation workers at B. anthracis-contaminated sites is warranted because inhalational anthrax is rapidly progressive and highly fatal, PPE does not guarantee 100% protection, and the risk for developing disease cannot be characterized adequately. The guidelines described here go beyond HAZWOPER requirements and include recommendations for treating inhalation exposure to B. anthracis spores as a medical emergency, medical follow-up as long as the risk for anthrax persists or a worker is receiving antibiotic prophylaxis, accommodation of a mobile workforce, and assurance that workers understand the need for immediate medical attention should symptoms of anthrax occur. Completion of the 6-dose series of anthrax vaccine followed by annual booster doses will decrease the reliance on antibiotics for the prevention of anthrax. Measures to protect workers must include both medical measures (i.e., vaccination, antibiotic prophylaxis, or a combination of both) and measures to prevent exposure (e.g., PPE and environmental controls). References

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/5/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/5/2002

|