|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

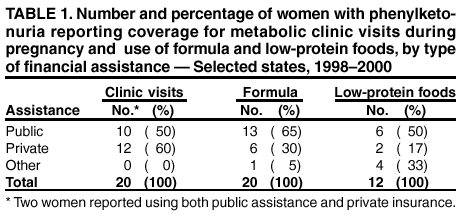

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Barriers to Dietary Control Among Pregnant Women with Phenylketonuria --- United States, 1998--2000Newborns in the United States are screened for phenylketonuria (PKU), a metabolic disorder that when left untreated is characterized by elevated blood phenylalanine (phe) levels and severe mental retardation (MR). An estimated 3,000--4,000 U.S.-born women of reproductive age with PKU have not gotten severe MR because as newborns their diets were severely restricted in the intake of protein-containing foods and were supplemented with medical foods (e.g., amino acid-modified formula and modified low-protein foods) (1--4). When women with PKU do not adhere to their diet before and during pregnancy, infants born to them have a 93% risk for MR and a 72% risk for microcephaly (5--6). These risks result from the toxic effects of high maternal blood phe levels during pregnancy, not because the infant has PKU (5--6). The restricted diet, which should be maintained for life, often is discontinued during adolescence (5--10). This report describes the pregnancies of three women with PKU and underscores the importance of overcoming the barriers to maintaining the recommended dietary control of blood phe levels before and during pregnancy. For maternal PKU-associated MR to be prevented, studies are needed to determine effective approaches to overcoming barriers to dietary control. During the fall of 2000, CDC conducted an interview-based study of women with PKU who were aged >18 years and pregnant during 1998--2000 (index pregnancy), regardless of dietary management or pregnancy outcome. Women were recruited from three metabolic clinics that provided services funded by state and private sources and were interviewed using a structured questionnaire that was completed in person or by telephone. Medical records were requested to document timing of diet initiation, control of blood phe levels (defined as 2--6 mg/dL), and pregnancy outcome. The study protocol was approved by CDC's Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from each respondent. A total of 30 women met the interview criteria; two could not be contacted. Of the 28 remaining women, 24 were interviewed (17 in person and seven by telephone). The median age was 28 years (range: 22--38 years); 75% were married, 96% were white, and 50% had a high school education or less. A total of 51 pregnancies had occurred among 24 women. Among the 24 index pregnancies, 18 (75%) resulted in live-born infants; 11 (46%) pregnancies were intended. The use of formula-based medical foods before conception was reported more often among the 11 women who were trying to conceive than among those who were not (risk ratio=3.5; 95% confidence interval=1.6--10.2). Use of modified, low-protein medical foods to diversify the diet was reported only among women trying to conceive. No difference was reported in avoiding high-protein foods between women who were and who were not trying to conceive. One woman remained on the restricted diet throughout adulthood; 23 women had been off the diet for 6--24 years (average: 16 years). At the time of the interview, 17 (71%) women were not using medical foods (65% because of the unpleasant taste). A total of 22 women had resumed the diet before or during their index pregnancy, eight (33%) women had contacted the metabolic clinic before conception, and 11 (46%) had contacted the metabolic clinic after conception but by week 10 of gestation. Of the 22 medical records available, 12 (55%) records indicated controlled blood phe levels before 10 weeks of gestation. All of the women expressed confidence in their metabolic clinic staff's knowledge of a phe-restricted diet and maternal PKU; eight (33%) perceived that their obstetricians were knowledgeable about maternal PKU. Approximately equal numbers of women used public assistance and private insurance to cover the costs associated with clinic visits (Table 1). Costs of medical foods were more often covered by public assistance than by private insurance (Table 1). Among the 13 women who used public assistance, nine (69%) reported that proof of pregnancy was required to receive services. When the data were stratified by state of residence, women in state C had the lowest rate of live births resulting from their pregnancies, lowest use of formula before pregnancy, fewest women achieving metabolic control before 10 weeks' gestation, and longest commutes to a metabolic clinic (Table 2). These differences were not significant by Fisher exact test. Case ReportsCase 1. A woman aged 21 years discontinued formula use in early adolescence and lost contact with the metabolic clinic. Although she was aware of the need to follow the diet during pregnancy, she did not seek care when she became pregnant. PKU was listed in her prenatal medical records; however, her obstetrician did not refer her to a metabolic clinic or a maternal-fetal specialist and did not recommend dietary intervention or regular monitoring of her phe levels. Her pregnancy resulted in an infant with microcephaly and developmental delay. Case 2. A woman aged 21 years discontinued formula use in early adulthood because of limited financial resources. She reported willingness to adhere to the diet during pregnancy, but lack of transportation, financial constraints, and inability to take time off from work prohibited her from accessing care at the nearest metabolic clinic, which was 3 hours away. She met with local health department staff several months into the pregnancy to acquire formula. PKU was included in her prenatal medical records, and she was referred to a maternal-fetal specialist; however, her blood phe levels were not monitored, and she was not referred to a metabolic clinic. Her pregnancy resulted in an infant with microcephaly. Case 3. A woman aged 27 years remained on the PKU diet throughout adulthood, planned her pregnancy, and had her blood phe levels in control before conception. Her private insurance covered part of her diet-related medical treatment costs. She estimated that out-of-pocket expenses for the portion of the metabolic clinic visits not paid by insurance were $2,300 during her pregnancy. Her insurer denied coverage for formula, low-protein foods, and blood tests to examine her full amino acid profile. The metabolic clinic provided the formula without reimbursement from the insurance company. Her pregnancy resulted in a healthy infant. Reported by: PM Fernhoff, MD, R Singh, PhD, Div of Medical Genetics, Dept of Pediatrics, Emory Univ School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. S Waisbren, PhD, F Rohr, MS, Children's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. DM Frazier, PhD, Div of Genetics and Metabolism, Univ of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. SA Rasmussen, MD, AA Kenneson, PhD, MA Honein, PhD, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities; ML Gwinn, MD, Office of Genetics and Disease Prevention, National Center for Environmental Health; and AS Brown, PhD, JM Morris, PhD, P MacDonald, PhD, EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:This report highlights some barriers that prevent metabolic control of blood phe levels before pregnancy among women with PKU. Two thirds of the women in this study had not followed the diet before becoming pregnant. This demonstrates limited adherence to prepregnancy medical recommendations among these women. Women also reported limited confidence in obstetricians' knowledge of maternal PKU management and inconsistencies between medical recommendations and health insurance coverage. Following the lifelong diet also was complicated by the unpleasant taste of medical foods. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, the sample size was small and consisted mostly of women who received dietary management from metabolic clinics during pregnancy. These women might have had access to more resources or been more willing to adhere to medical recommendations than women who had not received such care. Second, at the time of the interviews, most of the women were not following their diets; persons with PKU who are not on the diet might have difficulties with concentration and memory that could compromise the accuracy of their responses. Third, the three clinics participating in this study do not represent all U.S. metabolic clinics. To improve pregnancy outcomes for women with PKU, health-care providers should be trained to advise women to plan their pregnancies, return to diet, and stay on the diet for life. Additional evaluation is needed to ascertain the knowledge needed by obstetricians to guide women with PKU; third-party payers could identify disparities in financial assistance available to pregnant women with PKU and determine the most cost-effective approaches. Additional examination of these barriers would allow public health programs to establish effective methods to reduce obstacles and improve pregnancy outcomes for women with PKU. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 2/14/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 2/14/2002

|