|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

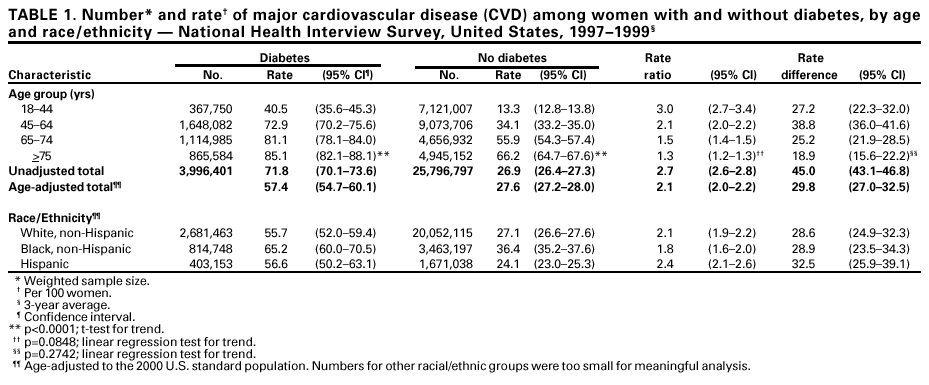

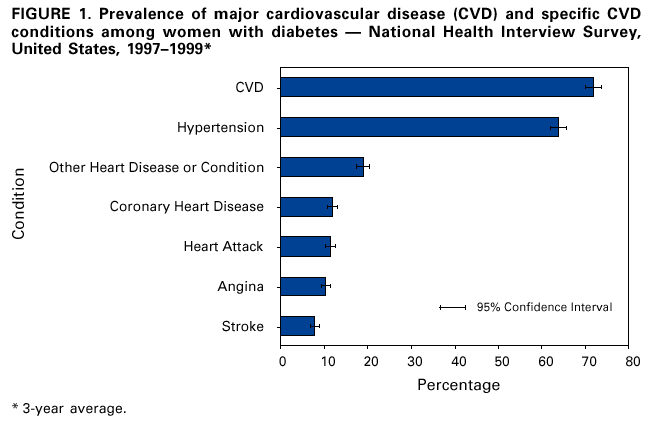

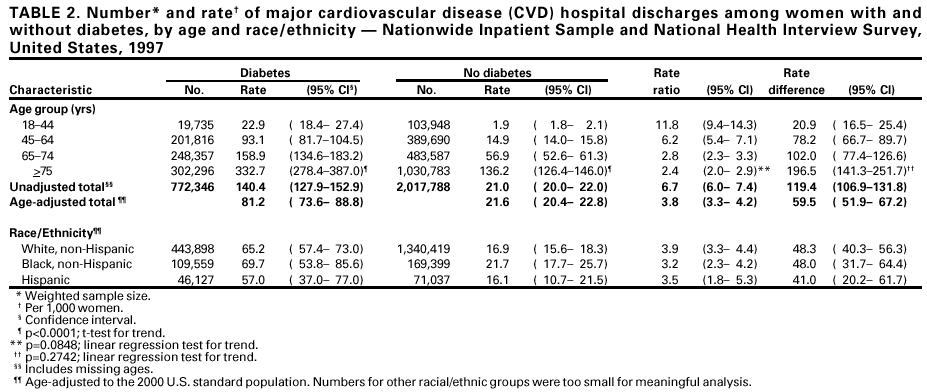

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Major Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) During 1997--1999 and Major CVD Hospital Discharge Rates in 1997 Among Women with Diabetes --- United StatesCardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death among all women (1) and the risk for death from CVD among women with diabetes is two to four times higher than that for women without diabetes (2). The excess risk for death as the result of CVD among persons with diabetes is better understood than the excess risk for CVD morbidity (2). To estimate national CVD prevalence and CVD hospital use among women with diabetes, CDC and the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) analyzed data from the 1997--1999 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the 1997 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Findings indicate that the age-adjusted prevalence of major CVD for women with diabetes is twice that for women without diabetes and that the age-adjusted major CVD hospital discharge rate for women with diabetes is almost four times the rate for women without diabetes. These findings underscore the need to reduce risk factors associated with CVD among all women with diabetes through focused public health and clinical efforts. The prevalence of CVD among women aged >18 years by diabetes status was obtained from a 3-year average of the estimates from the 1997--1999 NHIS, an ongoing nationally representative survey providing information on the health of the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population. Respondents were asked whether they had ever been told by a doctor or other health-care provider that they had hypertension, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, other kinds of heart conditions or heart disease, stroke, or diabetes. Major CVD was defined as one or more positive responses to the six CVD condition questions, and diabetes was defined as a positive response to the diabetes question. The number of major CVD hospital discharges was estimated from the 1997 NIS, a stratified probability sample of hospitals in 22 states. Discharges from the 22 states represented approximately 60% of all discharges in the United States. Sample data were weighted using the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals to approximate discharges from all U.S. acute-care community hospitals. Analysis was restricted to major CVD discharges (e.g., ischemic heart disease, hypertensive disease, rheumatic heart disease, and stroke) having an International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code of 390--448 as the first-listed diagnosis. Diabetes-related discharges were identified as those with an ICD-9 code of 250 as a secondary diagnosis. Major CVD discharge rates were calculated for the U.S. female population aged >18 years with and without diabetes by dividing the number of major CVD discharges estimated from NIS by the estimated number of women with and without diabetes obtained using 1997 NHIS data. Rate ratios and rate differences were calculated for both major CVD prevalence and hospital discharge rates by comparing rates for women with diabetes with those for women without diabetes. SUDAAN was used to calculate all estimates and their standard errors because of the complex sample designs of NIS and NHIS. Major CVD rates were age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population (3). Trends were assessed by age for major CVD prevalence and for hospital discharge rates, rate ratios, and rate differences. The difference between age-adjusted major CVD prevalence and hospital discharge rates by diabetes status across all racial/ethnic categories was assessed using z-tests; a t-test in SUDAAN was used to assess the difference in age-adjusted major CVD prevalence and hospital discharge rates by race/ethnicity, comparing non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics. Other racial/ethnic groups were not included because sample size was too small for meaningful analysis. During 1997--1999, 72% (95% confidence interval [CI]=+1.8%) of all women with diabetes self-reported having major CVD (Figure 1). The most common CVD condition was hypertension (64%; 95% CI=±1.8%) followed by other heart disease or conditions (19%; 95% CI=+1.5%), coronary heart disease (12%; 95% CI=+1.2%), heart attack (11%; 95% CI=+1.3%), angina (10%; 95% CI=+1.1%), and stroke (8%; 95% CI=+1.0%) (Figure 1). The prevalence of major CVD increased with age for women with diabetes from 40.5% (95% CI=+4.9%) for women aged 18--44 years to 85.1% (95% CI=+3.0%) for women aged >75 years (p<0.0001) (Table 1). The age-adjusted prevalence of major CVD among women with diabetes was twice that of women without diabetes (p<0.0001) (Table 1). Age-adjusted major CVD prevalence for women with diabetes was higher for non-Hispanic blacks (65.2%; 95% CI=+5.3%) than for non-Hispanic whites (55.7%; 95% CI=+3.7%) (p=0.004) or Hispanics (56.6%; 95% CI=±6.5%) (p=0.05). The rate ratio of major CVD in women with diabetes relative to women without diabetes ranged from 3.0 (95% CI=+0.4) for women aged 18--44 years to 1.3 (95% CI=+0.1) for those aged >75 years (p=0.09). Although rate differences were greatest among women aged 45--64 years and lowest among women aged >75 years, no significant trend by age was found (p=0.27) (Table 1). During 1997, 772,346 of all major CVD hospital discharges (28%) had diabetes as a secondary diagnosis (Table 2). Hospital discharge rates for major CVD among women with diabetes increased from 22.9 per 1,000 (95% CI=+4.5) for the youngest age group to 332.7 per 1,000 (95% CI=+54.3) for the oldest age group (p=0.0004) (Table 2). The age-adjusted major CVD hospital discharge rate for women with diabetes was 3.8 times that of women without diabetes (Table 2). No significant difference was found among racial/ethnic groups for major CVD hospital discharge rates among women with diabetes. The rate ratio comparing major CVD hospital discharges in women with diabetes with those without diabetes decreased with age from 11.8 per 1,000 (95% CI=+2.4) in the youngest age group to 2.4 per 1,000 (95% CI=+0.4) in the oldest (p=0.04). Rate differences increased with age from 20.9 per 1,000 (95% CI=+4.4) in the youngest to 196.5 per 1,000 (95% CI=+55.2) in the oldest (p=0.02) (Table 2). Reported by: Center for Organization and Delivery Studies, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland. Epidemiology and Statistics Br, Div of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:This report indicates that 72% of U.S. women with diabetes self-reported having major CVD. Major CVD prevalence is twice as common and major CVD hospitalizations are nearly four times as common among women with diabetes compared with women without diabetes. These findings are consistent with mortality studies documenting that women with diabetes are at much higher risk for death as a result of major CVD than women without diabetes (2). Clinical trials indicate that antihypertensive treatment (4), aspirin use (5), and lipid-lowering therapies (6) prevent or delay cardiovascular events. Epidemiologic evidence suggests that the risk for major CVD might be reduced through glycemic control (7) and the promotion of healthy lifestyles, including weight reduction/obesity prevention, increased physical activity, smoking cessation/prevention, and improved diet (7). Primary prevention of diabetes, a risk factor for major CVD, also can prevent major CVD. The Diabetes Prevention Program, a clinical trial examining the effect of intensive lifestyle intervention on the occurrence of type 2 diabetes in high-risk populations, concluded that improved diet, weight loss, and increased physical activity prevented or delayed the onset of diabetes among adults with impaired glucose tolerance (8). Despite the efficacy of prevention strategies for major CVD, a large proportion of persons with diabetes have uncontrolled blood pressure (9), dyslipidemia (9), and hyperglycemia (9) and do not take aspirin (5). Additional research is needed to learn how to improve the process and outcomes of care among persons with diabetes. A concerted effort among health-care providers, public health officials, members of community-based organizations, and patients and their families will be necessary to reduce major CVD among persons with diabetes. The high rate of major CVD among women with diabetes of all ages indicates that strategies for CVD risk reduction should be offered to all women with diabetes. Rate differences in hospital discharges increased with age, indicating that the effects of successful CVD prevention efforts should increase with age for women with diabetes. The findings in this study are subject to at least six limitations. First, NHIS data on history of diabetes and major CVD are self-reported; however, studies comparing self-reported with physician-reported medical history data have found no difference in the prevalence of diabetes, and self-reported prevalence rates for CVD and hypertension were only slightly higher than physician-reported rates (10). Second, because NHIS excludes the institutionalized population, the number of persons with major CVD and diabetes is underestimated. Third, because NIS data represent hospital discharges and not individual persons, patients with multiple CVD hospitalizations within 1 year were counted multiple times; this might have resulted in an overestimation of hospital discharge rates. Fourth, by not including data from long-term and federal hospitals, NIS underestimates major CVD hospitalizations. Fifth, race/ethnicity is missing for approximately 20% of hospital discharges in NIS; four states that contribute to NIS provided no information on race/ethnicity, and one state provided race/ethnicity for approximately 25% of discharges. Therefore, race/ethnicity rates might be underreported and might be biased if disease patterns vary differentially across the reporting and nonreporting states. Finally, because the NIS sample comprised only 22 states, these data might be biased and might differ from estimates of the National Hospital Discharge Sample . However, in 1997, both data sources produced similar estimates of discharges with diabetes as the primary diagnosis (AHRQ, unpublished data, 2000). CDC has published Diabetes and Women's Health Across the Life Stages: A Public Health Perspective that addresses the need for more research to gain a better understanding of the excess risk for major CVD among women with diabetes and to identify modifiable behavior and other determinants that can be used to develop effective interventions. The National Institutes of Health and CDC also have implemented the National Diabetes Education Program that includes public and private partners in the treatment and outcome of persons with diabetes; this program promotes early diagnosis to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with diabetes. CDC supports diabetes control programs in every state and, in 1998, initiated support for cardiovascular health promotion, disease prevention, and control programs. Since 1999, CDC has supported REACH 2010 (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health) to eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in numerous health areas, including diabetes and CVD. Additional information on diabetes is available at <http://www.cdc.gov/Diabetes>. References

Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 11/2/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 11/2/2001

|