|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

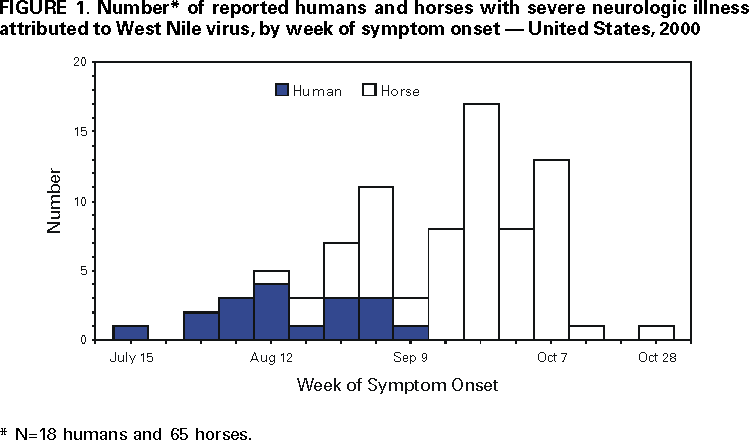

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Update: West Nile Virus Activity --- Eastern United States, 2000Please note: An erratum has been published for this article. To view the erratum, please click here. Data reported to CDC through the West Nile Virus (WNV) Surveillance System have shown an increase in the geographic range of WNV activity in 2000 compared with 1999, the first year that WNV was reported in the Western Hemisphere (1). In response to this occurrence of WNV, 17 states along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, New York City, and the District of Columbia conducted WNV surveillance, which included monitoring mosqui toes, sentinel chicken flocks, wild birds, and potentially susceptible mammals (e.g., horses and humans) (2). In 1999, WNV was detected in four states (Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York) (3). In 2000, epizootic activity in birds and/or mosquitoes was reported from 12 states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia) and the District of Columbia. Of the 13 jurisdictions, seven also reported severe neurologic WNV infections in humans, horses, and/or other mammal species. This report presents surveillance data reported to CDC from January 1 through November 15. During 2000, 18 (14 from New York and four from New Jersey) persons were hospitalized with severe central nervous system illnesses caused by WNV. Patients ranged in age from 36 to 87 years (mean: 62 years); 12 were men. Of the New York patients, 10 resided in Richmond County (Staten Island), two in Kings County (Brooklyn), one in Queens County, and one in New York County (Manhattan). Of the New Jersey patients, two resided in Hudson County, and one each in Bergen and Passaic counties. Epizootic activity in birds and/or mosquitoes preceded the onset of human illness in all of these counties. Diagnoses were confirmed either by ELISA for WNV-specific IgM in cerebrospinal fluid or by a four-fold rise in WNV-specific neutralizing antibody in paired serum samples. Dates of illness onset ranged from July 20 to September 13 (Figure 1). Of the 18 patients, one died (case fatality rate: 6%), and one is in a persistent vegetative state. In addition, WNV infection was documented in a mildly symptomatic woman residing in Fairfield County, Connecticut. Veterinary surveillance has identified WNV infections in 65 horses with severe neurologic disease from 26 counties in seven states (27 horses in New Jersey; 24 in New York; seven in Connecticut; four in Delaware; and one each in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island). Illness onsets in these horses ranged from August 15 to October 29 (Figure 1). WNV infection has been confirmed in 26 other mammals; of these, 25 were from 10 counties in New York (14 bats, four rodents, three rabbits, two cats, two raccoons), and one was from Connecticut (skunk). WNV was isolated from or WNV gene sequences were detected in 470 mosquito pools in 38 counties in five states (352 pools in New York, 54 in New Jersey, 46 in Pennsylvania, 14 in Connecticut, and four in Massachusetts). Of the 470 reported WNV-infected pools, Culex species accounted for 418, including 222 Cx. pipiens/restuans, 126 Cx. pipiens, 35 Cx. salinarus, 11 Cx. restuans, and 24 unspecified Cx. pools. Ochlerotatus species (formerly in Aedes genus) (4) accounted for 29 positive pools, including nine Oc. japonicus, nine Oc. triseriatus, eight Oc. trivittatus, and one each of three other Oc. species. Aedes species accounted for 18 positive pools, including 16 Ae. vexans, one Ae. albopictus, and one unspecified Ae. pool. In addition, WNV was detected in three pools of Culiseta melanura, one pool of Psorophora ferox, and one pool of Anopheles punctipennis. A total of 4139 WNV-infected dead birds were reported from 133 counties in 12 states (New York reported 1263 birds; New Jersey, 1125; Connecticut, 1116; Massachusetts, 442; Rhode Island, 87; Maryland, 50; Pennsylvania, 34; New Hampshire, seven; Virginia, seven; Delaware, one; North Carolina, one; and Vermont, one) and the District of Columbia (five). Crows were the most frequently reported WNV-infected species. Since 1999, WNV has been identified in 76 avian species in the United States. WNV infection also was documented in specimens collected from six previously seronegative sentinel chickens in six counties in two states (New Jersey, four and New York, two). Reported by: A Novello, MD, D White, PhD, L Kramer, PhD, C Trimarchi, MS, M Eidson, DVM, D Morse, MD, B Wallace, MD, P Smith, MD, State Epidemiologist, New York State Dept of Health; S Trock, DVM, New York State Dept of Agriculture; W Stone, MS, Dept of Environmental Conservation, Albany; B Cherry, VMD, J Kellachan, MPH, V Kulasekera, PhD, J Miller, MD, I Poshni, PhD, C Glaser, MPH, New York City Dept of Health, New York. W Crans, PhD, Rutgers Univ, New Brunswick; F Sorhage, VMD, E Bresnitz, MD, State Epidemiologist, New Jersey Dept of Health and Senior Svcs. T Andreadis, PhD, Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, New Haven; R French, DVM, Univ of Connecticut, Storrs; M Lis, DVM, Connecticut Dept of Agriculture; R Nelson, DVM, D Mayo, ScD, M Cartter, MD, J Hadler, MD, State Epidemiologist, Connecticut Dept of Public Health. B Werner, PhD, A DeMaria, Jr, MD, State Epidemiologist, Massachusetts Dept of Public Health. U Bandy, MD, State Epidemiologist, Rhode Island Dept of Health. J. Greenblatt, MD, State Epidemiologist, New Hampshire Dept of Health. P Keller, M Levy, MD, State Epidemiologist, District of Columbia Dept of Public Health. C Lesser, MS, Maryland Dept of Agriculture; R Beyer, C Driscoll, DVM, Maryland Dept of Natural Resources; C Johnson, DVM, J Krick, PhD, A Altman, MS, D Rohn, MPH, R Myers, PhD, L Montague, J Scaletta, MPH, J Roche, MD, State Epidemiologist, Maryland Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene. B Engber, ScD, N Newton, PhD, T McPherson, N MacCormack, MD, State Epidemiologist, North Carolina Dept of Health. G Obiri, DrPH, J Rankin, Jr, DVM, State Epidemiologist, Pennsylvania Dept of Health. P Tassler, PhD, P Galbraith, DMD, State Epidemiologist, Vermont Dept of Health. S Jenkins, VMD, R Stroube, MD, State Epidemiologist, Virginia Dept of Health. D Wolfe, MPH, H Towers, VMD, W Meredith, PhD, A Hathcock, PhD, State Epidemiologist, Delaware Div of Public Health. Animal, Plant, and Health Inspection Svc, US Dept of Agriculture. National Wildlife Health Center, US Geologic Survey, Madison, Wisconsin. P Kelley, MD, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, District of Columbia. M Bunning, DVM, US Air Force, Frederick, Maryland. Arbovirus Diseases Br, Div of Vector Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; and EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:Although the WNV epizootic has persisted in the four states originally affected in 1999 and expanded into eight additional states and the District of Columbia, only 18 humans with severe neurologic illness attributed to WNV were reported in 2000 compared with 62 in 1999 (5). However, severe neurologic illness occurs in <1% of infected persons, suggesting that approximately 2000 persons may have been infected during 2000. Although some decrease in severe human illness may be attributable to vector-control and other prevention activities, experience in Europe shows that the incidence of human illness can be variable and outbreaks sporadic (6). Because widespread WNV epizootic activity probably will persist and expand in the United States, larger outbreaks of WNV infection and human illness are possible if adequate surveillance, prevention activities, and mosquito control are not established and maintained. A major objective of WNV surveillance is to detect epizootic activity early so that intervention can occur before severe human illnesses. In 2000, all 18 persons with severe neurologic disease became ill after WNV-infected dead birds were identified in their county of residence, suggesting that avian surveillance data are a sensitive indicator of epizootic transmission that may portend human illness. However, of 133 counties reporting WNV-infected birds, only seven (5%) reported at least one person with severe neurologic illness. The presence of WNV-positive mosquito pools may indicate a greater potential for severe human illness as six (16%) of the 38 counties with positive pools reported at least one severely ill person. But these pools were identified before the onset of human illness in only five of these counties. Further analysis of 2000 surveillance data, including an assessment of the timing, number, and geographic location of WNV-infected birds, and an assessment of mosquito-trapping activities, infection rates, and species identified are required to further interpret these data. As occurred in 1999, the number of reported WNV illnesses in horses peaked and persisted after human illnesses (7). Although more data are needed to determine the reasons for this relative delay, it appears that horses are not a sensitive sentinel for the prediction of human illness. The continued geographic expansion of WNV indicates the need for expanded surveillance and prevention activities. Surveillance should include monitoring WNV infection in birds, humans, and veterinary species and in mosquitoes, particularly when WNV activity has been identified (5). Prevention should include programs that 1) eliminate mosquito-breeding habitats in public areas; 2) control mosquito larvae where these habitats cannot be eliminated; 3) promote the increased use of personal protection and the reduction of peridomestic conditions that support mosquito breeding; and 4) implement adult mosquito control when indicated by increasing WNV activity or the occurrence of human disease. In addition, because arbovirus infections are endemic in the continental United States, states should have a comprehensive plan and a functional arbovirus surveillance and response capacity that includes trained personnel with suitable laboratory support for identifying arbovirus activity, including WNV (5). References

Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 11/21/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|