|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

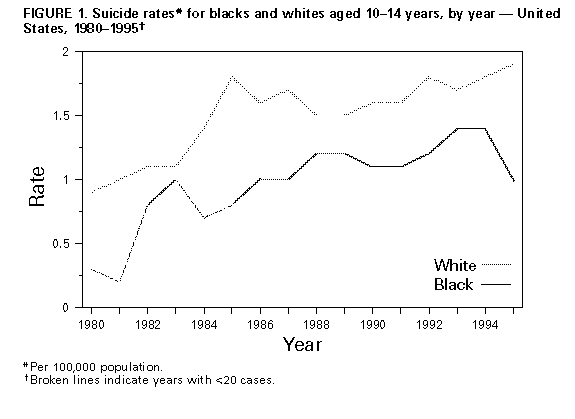

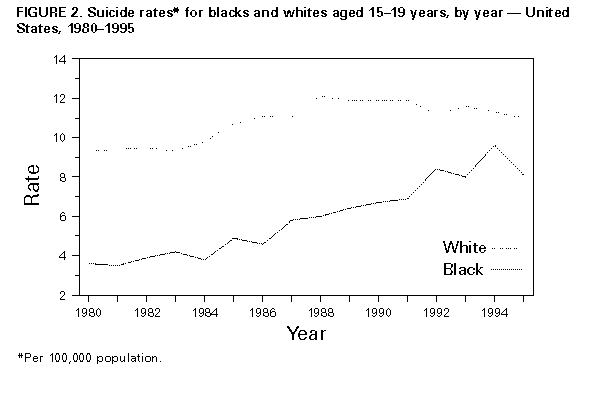

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Suicide Among Black Youths -- United States, 1980-1995Although black youths have historically had lower suicide rates than have whites, during 1980-1995, the suicide rate for black youths aged 10-19 years increased from 2.1 to 4.5 per 100,000 population. As of 1995, suicide was the third leading cause of death among blacks aged 15-19 years (1), and high school-aged blacks were as likely as whites to attempt suicide (2). This report summarizes trends in suicide among blacks aged 10-19 years in the United States during 1980-1995 and indicates that suicidal behavior among all youths has increased; however, rates for black youths have increased more, and the gap between rates for black and white youths has narrowed. Data for suicides were obtained from CDC's National Center for Health Statistics Underlying Cause of Death Mortality file (3) and were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision *. Population estimates were obtained from the Bureau of the Census decennial estimates for 1980 and 1990. Age-specific rates were calculated per 100,000 population. During 1980-1995, a total of 3030 blacks aged 10-19 years committed suicide in the United States. During this period, the suicide rate for blacks aged 10-19 years increased 114%. In 1980, the suicide rate for whites aged 10-19 years was 157% greater than the rate for blacks. By 1995, the rate for whites was only 42% greater than the rate for blacks. Among blacks and whites aged 10-19 years, the suicide rate increased most for blacks aged 10-14 years (233%), compared with a 120% increase for whites (Figure_1). Among blacks aged 15-19 years, the suicide rate increased 126%, compared with 19% for whites (Figure_2). Among black males aged 15-19 years, the suicide rate increased 146%, compared with 22% for white males. Firearms use was the predominant method of suicide for blacks aged 10-19 years, accounting for 66% of suicides in this group. Among blacks aged 15-19 years, firearms use accounted for 69% of suicides, followed by strangulation (18%). Among black males aged 15-19 years, firearms use accounted for 72% of suicides, followed by strangulation (20%). Firearm-related suicides accounted for 96% of the increase in the suicide rate for blacks aged 10-19 years. During 1980-1995, trends in suicide rates for black youths differed by region. ** The largest increase in suicide rates occurred for blacks aged 15-19 years in the South (214%), followed by the Midwest (114%). By sex, the largest increase in suicides occurred among black males aged 15-19 years in the South (223%). Reported by: Div of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: Although suicides have increased overall among youths (4), the findings in this report indicate that, during 1980-1995, suicide rates for black youths have increased substantially, particularly in the South. In addition, the difference in suicide rates for blacks and whites has decreased substantially. Risk factors associated with suicides among youth include hopelessness; depression; family history of suicide; impulsive and aggressive behavior; social isolation; a previous suicide attempt; and easier access to alcohol, illicit drugs, and lethal suicide methods (5). Changes in some risk factors (e.g., breakdown of the family and easier access to alcohol, illicit drugs, and lethal suicide methods) may account for the increasing suicide rate among youths. However, these changes may not account for the increase in suicides among blacks aged 10-19 years. One possible factor may be the growth of the black middle class (6). Black youths in upwardly mobile families may experience stress associated with their new social environments. Alternatively, these youths may adopt the coping behaviors of the larger society in which suicide is more commonly used in response to depression and hopelessness (7). Another factor may be differential recording of suicide as a cause of death on death certificates. Suicide as a cause of death may be entered less readily for black youths than for white youths (8). In addition, risk factors associated with suicide among youths in general may not predict suicidal behaviors among black youths. Differences in the social environments and life experiences of black and white youths suggest the need to determine whether risk factors for suicide in black youths differ from those of whites. For example, the exposure of black youths to poverty, poor educational opportunities, and discrimination may have negatively influenced their expectations about the future and, consequently, enhanced their resiliency to suicide (9). Although youth suicide prevention programs exist, little is known about their effectiveness in reducing suicidal behavior (10). These programs also may not address the risk factors associated with the increasing suicide rates for black youths. If risk factors for suicide differ for black and white youths, existing programs for suicide prevention that target black youths may need to be modified. A better understanding of the risk factors associated with suicide among black youths is needed to develop appropriate prevention and treatment programs. Evaluations of existing programs to prevent youth suicide should examine the potential for differential effects on black youths. References

* Suicide codes were for poisoning (E950.0-E952.9), strangulation (E953.0-953.9), firearms use (E955.0-E955.4), and cutting (E956.0-E956.9). ** Northeast=Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Midwest=Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South=Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; West=Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Figure_1  Return to top. Figure_2  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 10/05/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|