|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

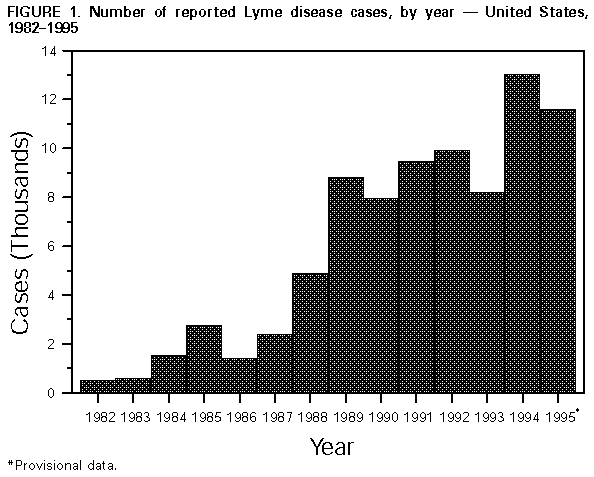

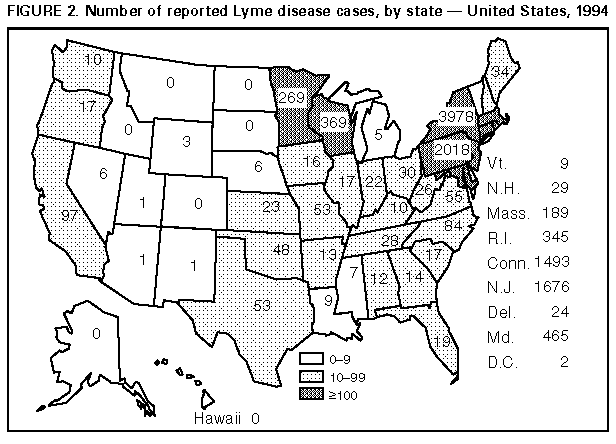

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Lyme Disease -- United States, 1995Lyme disease (LD) is caused by the tickborne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Surveillance for LD was initiated by CDC in 1982 and, during 1990, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists designated LD as a nationally notifiable disease. For surveillance purposes, LD is defined as the presence of an erythema migrans rash greater than or equal to 5 cm in diameter or laboratory confirmation of infection with objective evidence of musculoskeletal, neurologic, or cardiovascular disease (1). This report summarizes cases of LD reported by state health departments to CDC during 1995 and indicates that the number of reported cases declined slightly from 1994. In 1995, 11,603 cases of LD were reported to CDC by 43 states and the District of Columbia (overall incidence 4.4 per 100,000 population), the second highest annual number reported since 1982 but an 11% decrease from the 13,043 cases reported in 1994 (Figure_1). As in previous years, the highest numbers of cases were reported from the northeastern, north-central, and mid-Atlantic regions (Figure_2). Incidences greater than 4.4 per 100,000 were reported by eight states, all in established LD-endemic regions (Connecticut {45.6}, Rhode Island {34.9}, New York {21.9}, New Jersey {21.1}, Pennsylvania {16.7}, Maryland {9.2}, Wisconsin {7.2}, and Minnesota {5.8}); these states accounted for 10,640 (92%) of reported cases. In 1995, no LD cases were reported from Alaska, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, or South Dakota. Sixty-three counties each reporting greater than or equal to 20 cases accounted for 78% of all reported cases. Reported incidences were greater than 100 per 100,000 in 14 counties in Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin; the highest reported incidence was in Nantucket County, Massachusetts (838.8) (Figure_3). Compared with 1994, the number of LD case reports in 1995 decreased by 113 (89%) in Georgia, 82 (77%) in Delaware, 76 (58%) in Virginia, 51 (52%) in Oklahoma, 49 (48%) in Missouri, 126 (27%) in Rhode Island, 537 (26%) in Connecticut, and 1222 (24%) in New York. Reported cases increased by 580 (40%) in Pennsylvania and by 61 (29%) in Minnesota. In the remaining states, numbers of reported cases remained stable. The highest proportions of cases occurred among persons aged 0-14 years (2760 {24%}) and adults aged 35-49 years (2797 {24%}). Reported by: State health departments. Bacterial Zoonoses Br, Div of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: The number of reported LD cases has increased steadily from 1982 through 1995, possibly reflecting increased recognition and reporting compliance and a true increase in incidence. The slight decline in the number of LD cases reported in 1995 from 1994 may have resulted from changes in these factors or a decrease in populations of Ixodes scapularis, the principal tick vector in the northeastern and north-central United States, as a result of variations in the environment. For example, light snowfall and dry spring conditions in Rhode Island during 1995 have been temporally associated with a 33% decline in the population of

Decreases in the number of reported LD cases in Georgia and Missouri may reflect 1) increased awareness among health-care providers that LD is not endemic in these states and 2) the possibility that some tickborne rashes may be related to another etiology. No cases in Missouri or the southern states have been confirmed by isolation of B. burgdorferi. An LD-like illness among some patients in Georgia and Missouri is characterized by a localized, expanding circular skin rash, similar to erythema migrans, and negative serology for B. burgdorferi (2). An uncultivable spirochete (B. lonestari sp. nov) identified in lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum) collected from Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, and Texas has been postulated as the possible etiologic agent (3). Vaccines to protect against LD are in advanced stages of development and evaluation. However, personal protection measures (e.g., applying tick repellants and inspecting for ticks) and environmental modifications (e.g., applying insecticides and using deer fencing) will continue to be important methods for reducing the risk for exposure to tick bites and preventing LD and other tickborne diseases (e.g., ehrlichiosis and babesiosis) (4-6). To enable optimal treatment of patients, clinical and laboratory data must be used to distinguish between these diseases, and the possibility of coinfection with more than one agent should be considered (7,8). Early stages of LD usually are treated with amoxicillin or doxycycline; the treatments of choice for ehrlichiosis and babesiosis are tetracyclines and clindamycin/quinine, respectively (9). Participants in the Second National Conference on the Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease (October 1994) recommended that laboratories use a two-test approach for the serologic diagnosis of LD. Specimens should be tested first by using the more sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). Specimens that are positive or equivocal then should be tested with the more specific IgG and IgM Western blot (WB). Because sensitivity and specificity of the ELISA and WB vary in relation to the timing of specimen acquisition, clinical and exposure histories must be considered in the interpretation of serologic results (10).

Figure_1  Return to top. Figure_2  Return to top. Figure_3  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|