|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

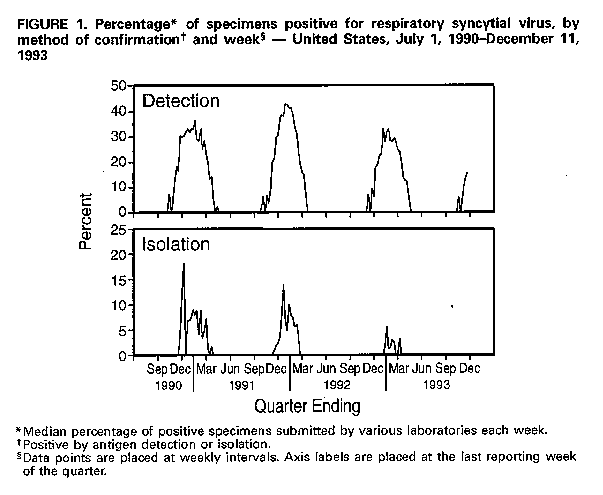

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Update: Respiratory Syncytial Virus Activity -- United States, 1993Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a common cause of communitywide outbreaks of acute respiratory disease, is associated with an estimated 90,000 hospitalizations and 4500 deaths from lower respiratory tract disease in both infants and young children in the United States (1). Outbreaks usually occur from late fall or early winter through spring. Since 1989, RSV activity in the United States has been monitored by the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS), a voluntary, laboratory-based system. This report summarizes surveillance results from NREVSS for RSV detections from July 1, 1993, through December 11, 1993, and assesses trends in RSV from July 1, 1990, through December 11, 1993. A total of 69 laboratories (hospital-based, public health, and free-standing) that participate in NREVSS in 39 states report weekly to CDC the number of specimens tested for RSV by the antigen-detection and virus-isolation methods and the number of positive results. Onset of RSV activity is defined by NREVSS as the first of 2 consecutive weeks when at least half of participating laboratories reported any RSV detections or isolations. As of November 30, 1993, 36 (59%) of the 61 laboratories reporting detections noted an increase in RSV-positive results, indicating the onset of outbreak activity for the 1993-94 winter season. By December 11, the median percentage positive had increased to 16.7%. During the three preceding seasons (i.e., 1990-91, 1991-92, and 1992-93), nationwide onset of RSV outbreak activity began during the last week of October through mid-December; activity peaked during January-February (Figure_1). Although the timing of the peak in the percentage of specimens positive for individual laboratories varied, these peaks usually occurred within 1 month of the national peak. Reported by: Emory Univ School of Public Health, Atlanta. National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System laboratories. Respiratory and Enteric Virus Br, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: With the onset of the 1993-94 RSV season, health-care providers should consider the role of RSV as a cause of acute respiratory disease in both children and adults. Most severe manifestations of infection with RSV (e.g., pneumonia and bronchiolitis) occur in infants aged 2-6 months; however, children of any age with underlying cardiac or pulmonary disease or who are immunocompromised are at risk for serious complications from this infection. Because natural infection with RSV provides limited protective immunity, RSV may cause repeated symptomatic infections throughout life. In adults, RSV usually causes upper respiratory tract manifestations but may cause lower respiratory tract disease- -especially in the elderly and in persons with compromised immune systems. RSV is a common, but preventable, cause of nosocomially acquired infection; the risk for nosocomial transmission is increased during community outbreaks. Sources for nosocomially acquired infection include infected patients, staff, visitors, or contaminated fomites. Nosocomial outbreaks or transmission of RSV can be controlled with strict attention to contact-isolation procedures (2). In addition, chemotherapy with ribavirin is indicated for some patients (e.g., those at high risk for severe complications or who are seriously ill with this infection) (3); prophylaxis with intravenous RSV immunoglobulin for high-risk patients may become available during future RSV seasons (4). References

Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|