|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

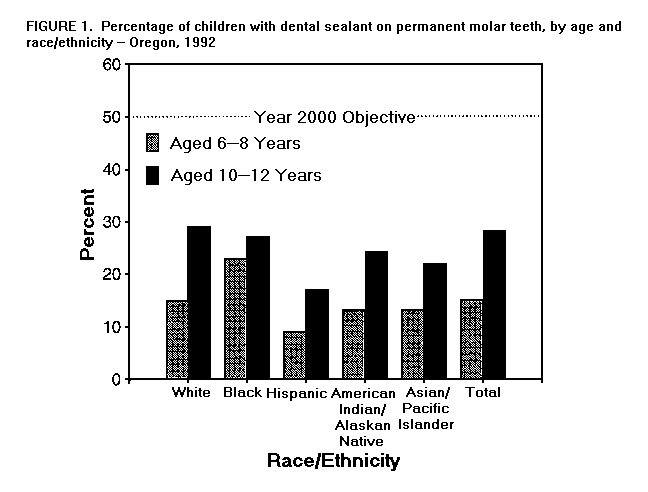

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Dental Health of School Children -- Oregon, 1991-92Dental caries remains among the most prevalent diseases of both children and adults. To establish a baseline for monitoring oral disease trends in Oregon, the State Health Division, Oregon Department of Human Resources; Oregon Health Sciences University; and Multnomah County Health Department collaborated in a statewide assessment of oral health needs. Phase 1 (1991-92) evaluated Head Start and elementary school children. Phase 2 (1993) is assessing the oral health of adults. This report presents the results of Phase 1. The study population was a convenience sample of 2872 Head Start and elementary school children. Seventeen communities representing all of the state's 13 administrative districts were selected to ensure that certain age and racial/ethnic groups were included in the survey. Elementary schools within each community were selected randomly. In the elementary schools, students in first and second grades (aged 6-8 years) and fifth and sixth grades (aged 10-12 years) who returned consent forms (n=2084, approximately 40% of the children in those classes) were examined for dental caries and other oral conditions. Head Start children aged 3-5 years (n=788) were examined at five different programs within the state. Two dental professionals completed clinical examinations following the protocol and criteria used for prevalence surveys conducted by the National Institute of Dental Research (1). Among children aged 3-5 years, 47% had experienced dental caries (Table_1). Among these children, 4% needed urgent dental care (i.e., had signs of a dental abscess or a statement that the child had been awakened at night by dental pain), 26% needed routine restorative treatment, and 17% had fillings but no active decay. Among children aged 6-8 years, 55% had experienced dental caries in their permanent or primary teeth or in both (Table_1): 5% required urgent care, 23% needed routine restorative treatment, 24% had had all of their carious lesions filled, and 3% had primary anterior teeth that were decayed but might not require treatment because exfoliation was imminent (i.e., teeth already were loose or all other disease had been treated). Fifteen percent of these children had dental sealant on at least one permanent molar tooth (Figure_1). Among children aged 10-12 years, 2% required urgent care, 20% needed routine restorative treatment, and 24% had all decay treated. Twenty-eight percent of the students had had dental sealant on at least one permanent molar tooth (Figure_1). When the data were stratified by race/ethnicity, children of minority groups had higher prevalences of dental caries and untreated disease (Table_1). For example, among children aged 6-8 years, American Indians/Alaskan Natives had the highest prevalence of disease, and higher proportions of Asians/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and American Indians/Alaskan Natives required dental treatment. When the data were stratified by urban (greater than or equal to 10,000 population)/rural status, differences appeared in the proportion of children in need of dental care, even among racial/ethnic groups with the lowest disease rates. For example, among 10-12-year-old white children, 16% in urban areas and 26% in rural areas needed dental treatment (p=0.1). Reported by: KR Phipps, DrPH, JD Mason, MPH, Oregon Health Sciences Univ, Portland; DW Fleming, MD, State Epidemiologist, State Health Div, Oregon Dept of Human Resources. Surveillance, Investigations, and Research Br, Div of Oral Health, National Center for Prevention Svcs, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: The findings in this report indicate that substantial differences in oral health status exist among racial/ethnic groups. In addition, Oregon must make substantial progress to achieve the national health objectives for the year 2000 regarding oral health (objectives 13.1, 13.2, and 13.8) (2). These data are the first systematic comparison of dental caries prevalence among multiple racial/ethnic groups in a specific geographic area and among the first compiled during the 1990s for evaluating progress of an individual state toward achievement of the national health objectives regarding oral health. Variations in oral health status among racial/ethnic groups may reflect other characteristics associated with a history of dental caries. Higher prevalence of dental caries and untreated disease have been found among children of parents who have lower educational levels and incomes (3,4); are members of immigrant groups that remain less acculturated (5); lack dental insurance coverage (6); and live in rural areas (1,3). In this sample, larger proportions of American Indian/Alaskan Native and Hispanic children lived in rural areas. The prevalence of dental sealant among children in this survey exceeds that found in surveys in other geographic areas (2,3,7) but does not approach the national health objective of 50%. The higher proportion of blacks aged 6-8 years with dental sealant on their first permanent molars may be associated with the county in which most blacks in Oregon live (Multnomah County {Portland}), which operates a school-based program to apply dental sealant. In addition, public health personnel in Oregon may emphasize dental sealant programs because relatively few children have access to fluoridated water. Oregon remains among the states and territories with the smallest proportion of its population receiving fluoridated water at optimal levels (8). Although water fluoridation for larger water systems is particularly cost-effective (9), only 11 of 39 Oregon cities or census-defined places with populations greater than or equal to 10,000 and only one of three cities with greater than or equal to 100,000 persons (1990 census) are fluoridated. Several factors may contribute to the observed urban/rural differences in treatment needs. Community- and school-based programs may not exist in many rural areas, thus limiting access to primary preventive measures such as fluoridated water, fluoride mouthrinse, or dental sealant. In addition, access to care may be restricted in rural areas because most dentists practicing in these areas may not be "active" * Medicaid providers. Reaching preschool children before dental caries occurs will require the cooperation of other health professionals. During well-child appointments, primary-care providers (e.g., pediatricians and nurse practitioners) should screen and refer young children for oral health prevention services (10). Although the sample in Oregon was selected to ensure representation of all racial/ethnic groups and to allow comparison of their dental caries rates, anecdotal reports suggest that the participation level (40%) was adversely affected by sending informed consent forms home with children; by parents' perception that children who receive regular dental care need not participate in the survey; and by concerns about transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in clinical dental settings. A dental survey requires trained examiners and substantial travel. Because such surveys are costly, they are conducted infrequently. Current data are essential for planning programs that use resources most effectively; therefore, alternate methods for routine assessment of oral health status (e.g., telephone interview data and respondent-assessed measures) must be developed and validated. References

* Defined by the Oregon Health Division as having filed 50 or more

Medicaid claims during the preceding fiscal year.

TABLE 1. Dental health status of school children, by age group and racial/ethnic group

-- Oregon, 1991-92

=========================================================================================

American

Indian/ Asian/

Alaskan Pacific

White Black Hispanic Native Islander Total

Age group (n=2229) (n=221) (n=224) (n=95) (n=103) (n=2872)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(n=515) (n=117) (n=82) (n=51) (n=23) (n=788)

------- ------- ------ ------ ------ -------

3-5 yrs

With dental caries * 46% 36% 52% 71% 57% 47%

Needing treatment 28% 21% 35% 55% 26% 30%

(n=1168) (n=56) (n=113) (n=23) (n=48) (n=1408)

-------- ------ ------- ------ ------ --------

6-8 yrs

With dental caries + 52% 64% 65% 91% 67% 55%

Needing treatment 26% 29% 43% 43% 46% 28%

(n=546) (n=48) (n=29) (n=21) (n=32) (n=676)

------- ------ ------ ------ ------ -------

10-12 yrs

With dental caries & 44% 48% 48% 62% 69% 46%

Needing treatment 21% 23% 21% 29% 38% 22%

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* Primary teeth only.

+ Primary and permanent teeth.

& Permanent teeth only.

=========================================================================================

Return to top. Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|