|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

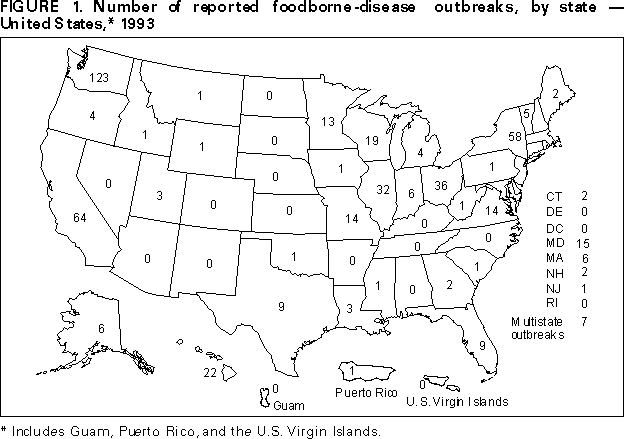

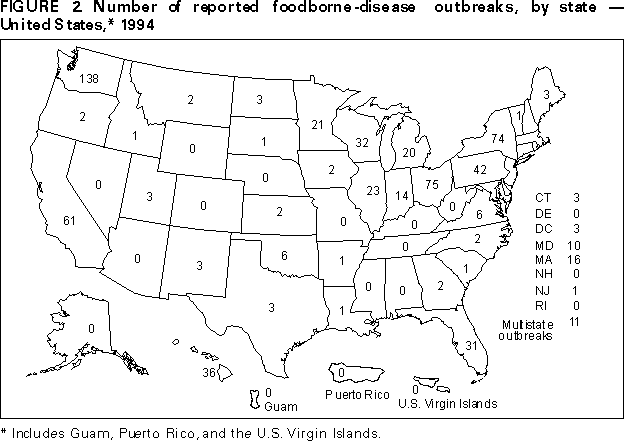

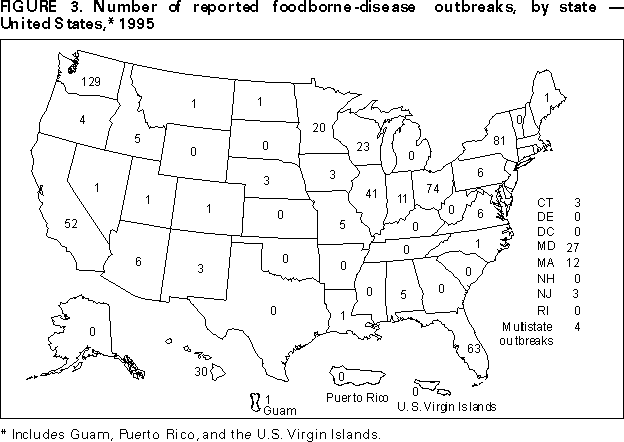

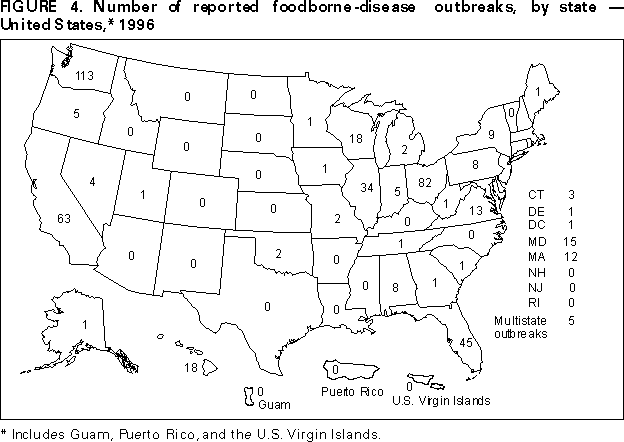

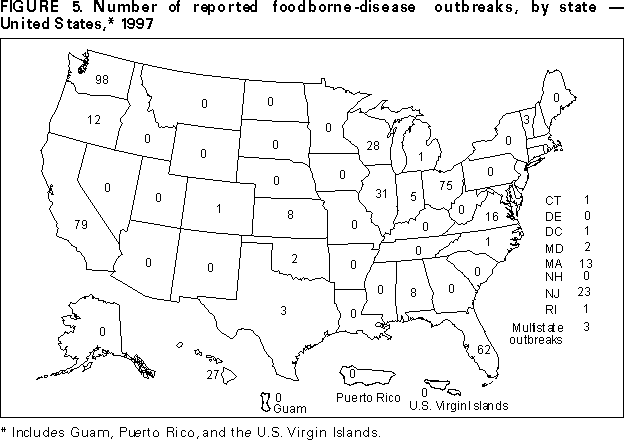

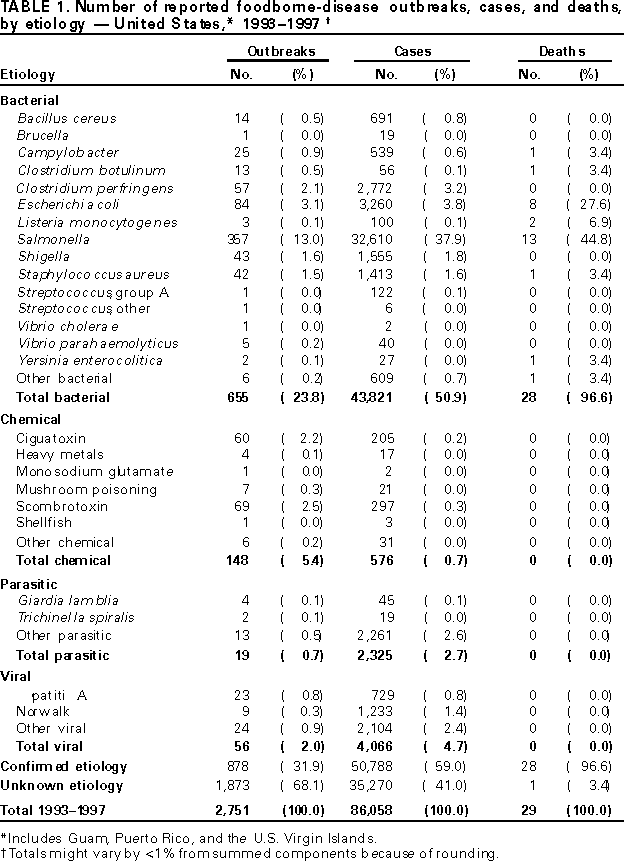

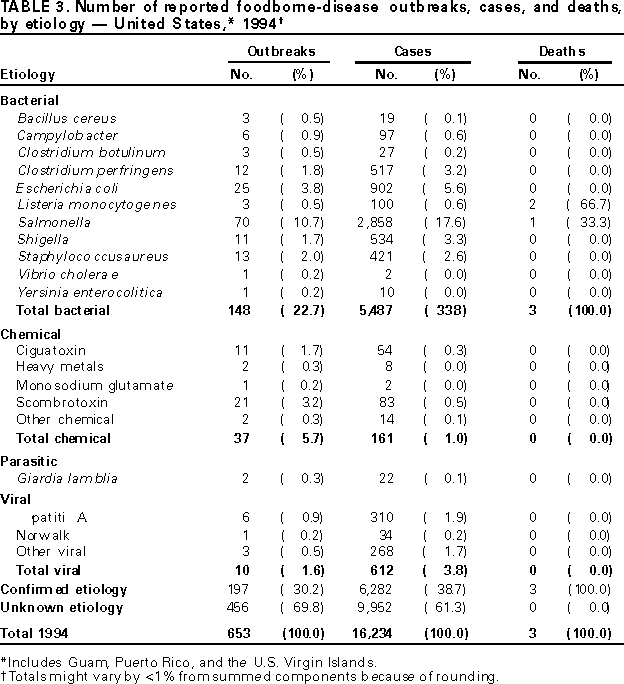

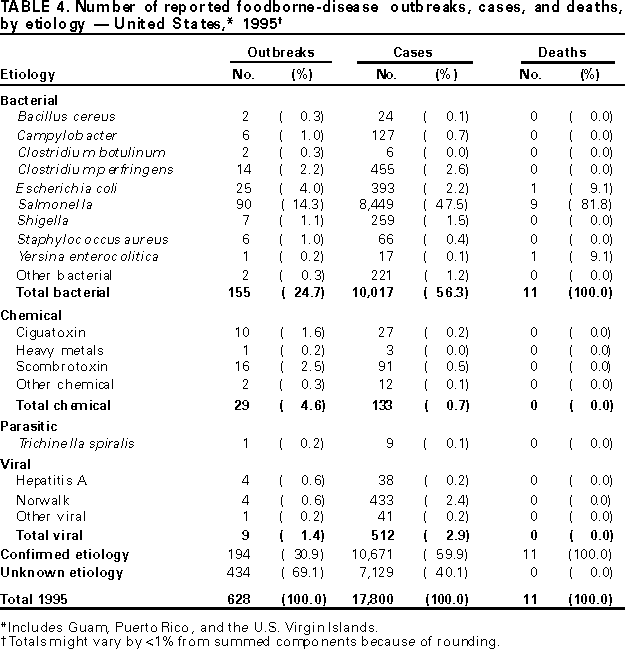

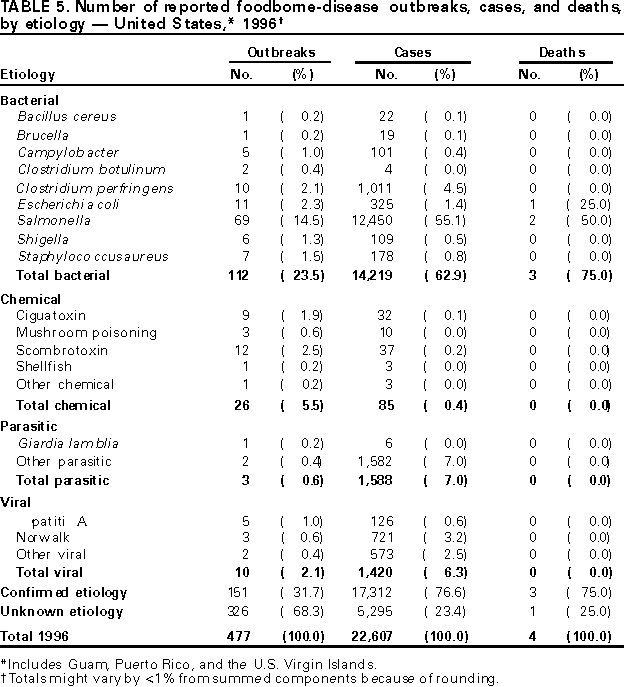

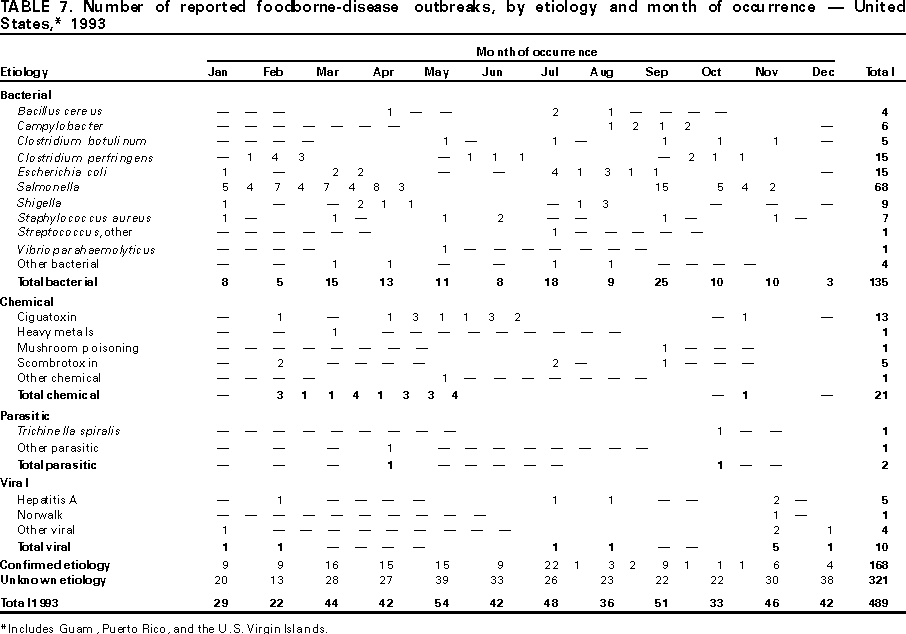

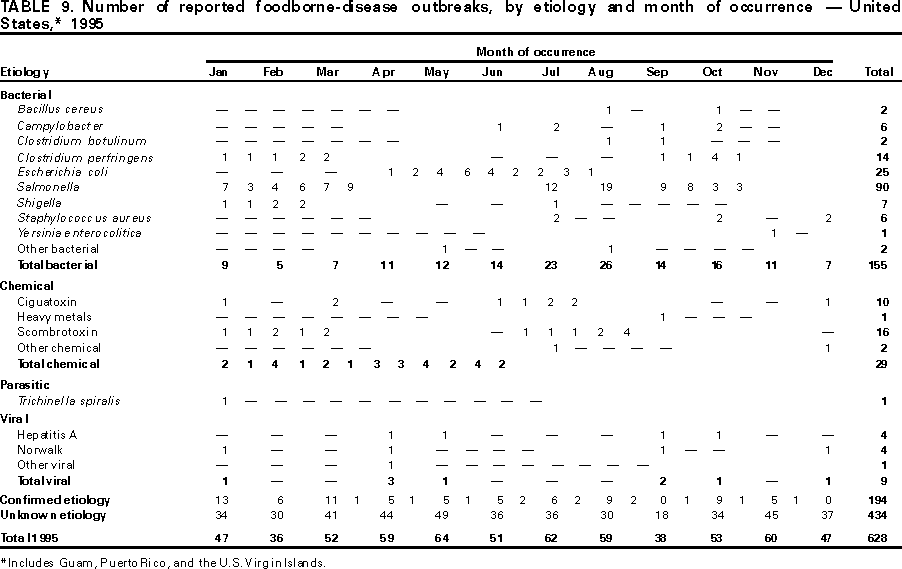

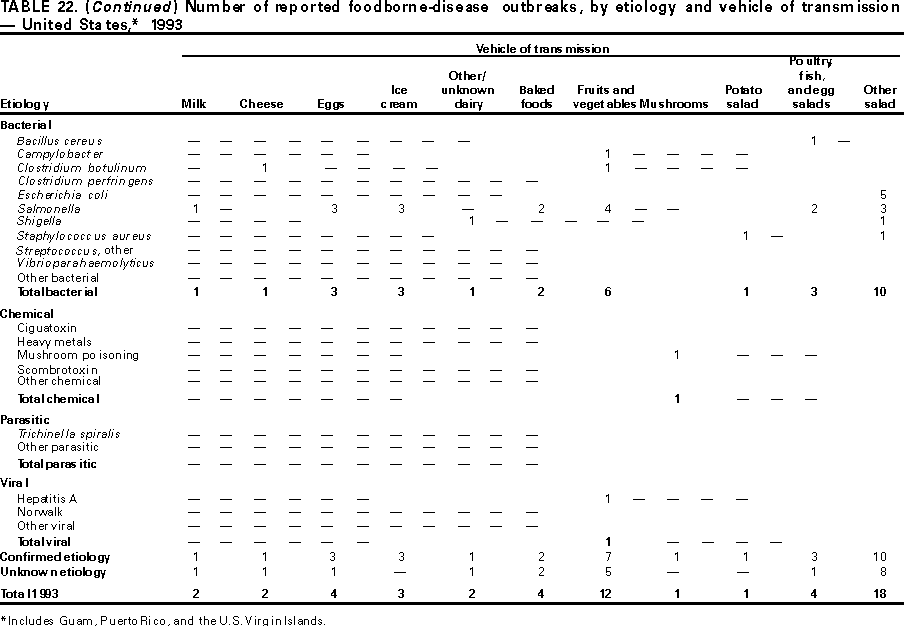

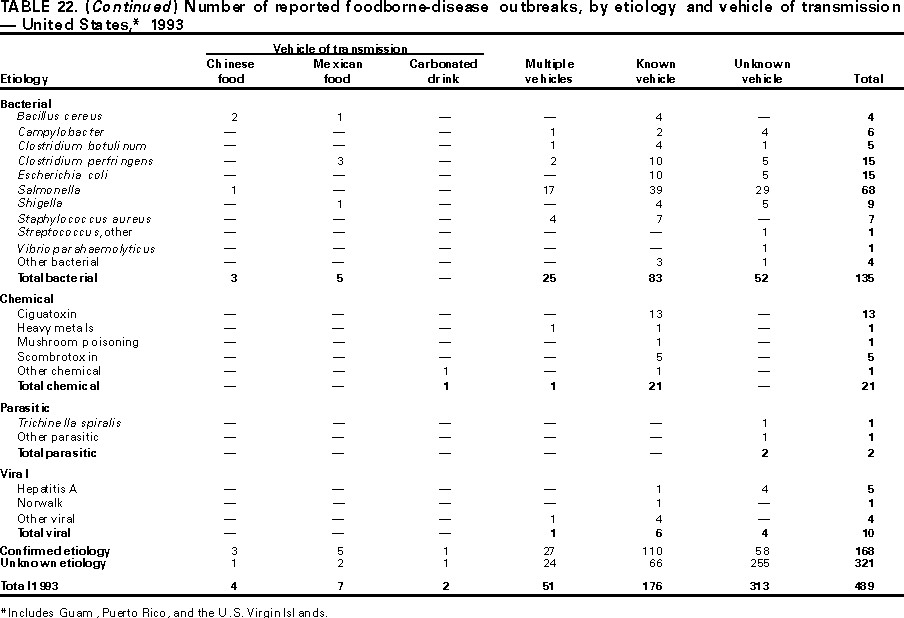

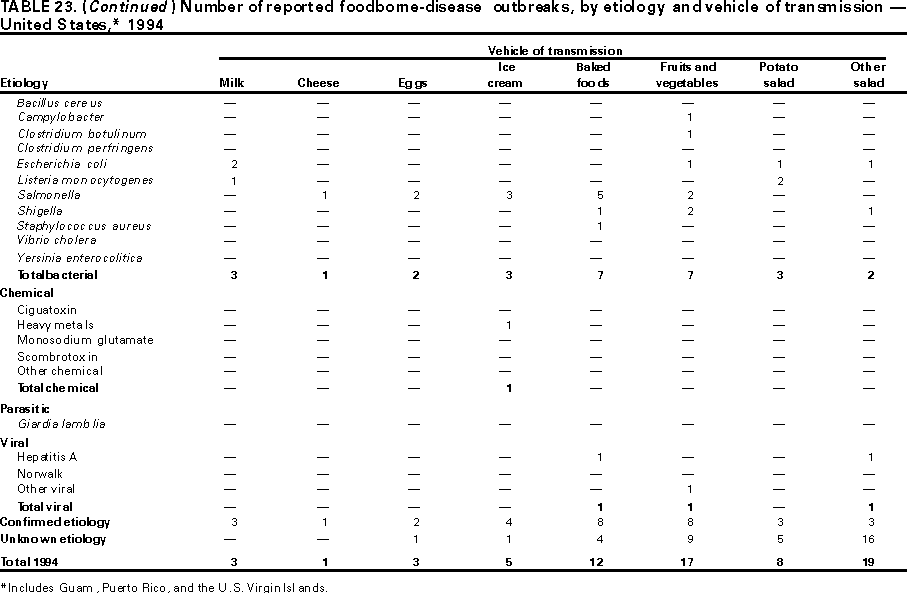

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks --United States, 1993-1997Please note: An erratum has been published for this article. To view the erratum, please click here. Sonja J. Olsen, Ph.D. Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases Abstract Problem/Condition: Since 1973, CDC has maintained a collaborative surveillance program for collection and periodic reporting of data on the occurrence and causes of foodborne disease outbreaks (FBDOs) in the United States. Reporting Period Covered: This summary reviews data from January 1993 through December 1997. Description of System: The Foodborne-Disease Outbreak Surveillance System reviews data concerning FBDOs, defined as the occurrence of two or more cases of a similar illness resulting from the ingestion of a common food. State and local public health departments have primary responsibility for identifying and investigating FBDOs. State, local, and territorial health departments use a standard form to report these outbreaks to CDC. Results: During 1993-1997, a total of 2,751 outbreaks of foodborne disease were reported (489 in 1993, 653 in 1994, 628 in 1995, 477 in 1996, and 504 in 1997). These outbreaks caused a reported 86,058 persons to become ill. Among outbreaks for which the etiology was determined, bacterial pathogens caused the largest percentage of outbreaks (75%) and the largest percentage of cases (86%). Salmonella serotype Enteritidis accounted for the largest number of outbreaks, cases, and deaths; most of these outbreaks were attributed to eating eggs. Chemical agents caused 17% of outbreaks and 1% of cases; viruses, 6% of outbreaks and 8% of cases; and parasites, 2% of outbreaks and 5% of cases. Interpretation: The annual number of FBDOs reported to CDC did not change substantially during this period or from previous years. During this reporting period, S. Enteritidis continued to be a major cause of illness and death. In addition, multistate outbreaks caused by contaminated produce and outbreaks caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7 remained prominent. Actions Taken: Current methods to detect FBDOs are improving, and several changes to improve the ease and timeliness of reporting FBDO data are occurring (e.g., a revised form to simplify FBDO reporting by state health departments and electronic reporting methods). State and local health departments continue to investigate and report FBDOs as part of efforts to better understand and define the epidemiology of foodborne disease in the United States. At the regional and national levels, surveillance data provide an indication of the etiologic agents, vehicles of transmission, and contributing factors associated with FBDOs and help direct public health actions to reduce illness and death caused by FBDOs. INTRODUCTION The reporting of foodborne and waterborne diseases in the United States began greater than 60 years ago when state and territorial health officers, concerned about the high morbidity and mortality caused by typhoid fever and infantile diarrhea, recommended that cases of "enteric fever" be investigated and reported. The purpose of investigating and reporting these cases was to obtain information regarding the role of food, milk, and water in outbreaks of intestinal illness as the basis for public health action. Beginning in 1925, the Public Health Service published summaries of outbreaks of gastrointestinal illness attributed to milk (1). In 1938, it added summaries of outbreaks caused by all foods. These early surveillance efforts led to the enactment of important public health measures (e.g., the Pasteurized Milk Ordinance) that led to decreased incidence of enteric diseases, particularly those transmitted by milk and water (2). From 1951 through 1960, the National Office of Vital Statistics reviewed reports of outbreaks of foodborne illness and published annual summaries in Public Health Reports. In 1961, CDC -- then the Communicable Disease Center -- assumed responsibility for publishing reports concerning foodborne illness. During 1961-1965, CDC stopped publishing annual reviews but reported pertinent statistics and detailed individual investigations in the MMWR. The present system of surveillance for foodborne and waterborne diseases began in 1966 when reports of enteric disease outbreaks attributed to microbial or chemical contamination of food or water were incorporated into an annual summary. Since 1966, the quality of investigative reports has improved greatly, with more active participation by state and federal epidemiologists in outbreak investigations. Outbreaks of waterborne diseases and foodborne diseases have been reported in separate annual summaries since 1978 because of increased interest and activity in surveillance for waterborne diseases. Previous summaries of data reported to the Foodborne-Disease Outbreak Surveillance System were published for 1983-1987 (3) and 1988-1992 (4). Surveillance has served three purposes:

The objective of this report is to summarize epidemiologic data on foodborne-disease outbreaks (FBDOs) reported to CDC from 1993 through 1997. METHODS Sources of Data for the Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System Agencies use a standard form (CDC Form 52.13, Investigation of a Foodborne Outbreak) to report FBDOs to CDC. A revised form became effective October 1999; this report summarizes data collected with the old form (Appendix A). Most reports are submitted by state, local, and territorial health departments; however, they also can be submitted by federal agencies and other sources. CDC reviews data on the forms to determine whether a specific food vehicle and etiologic agent have been confirmed for an outbreak (Appendix B). In some instances, questions concerning etiology are referred back to the reporting agencies. Definition of Terms An FBDO is defined as the occurrence of two or more cases of a similar illness resulting from the ingestion of a common food.* Laboratory or clinical guidelines for confirming an FBDO outbreak vary for bacterial, chemical, parasitic, and viral agents (Appendix B, Table B). Outbreaks of unknown etiology are divided into four subgroups according to incubation period of the illness: less than 1 hour (probable chemical poisoning); 1-7 hours (probable Staphylococcus aureus or Bacillus cereus food poisoning); 8-14 hours (other agents); nd greater than or equal to 15 hours (other agents). Limitations of the Surveillance System Several types of outbreaks are excluded from the Foodborne-Disease Outbreak Surveillance System such as outbreaks that occur on cruise ships (these are summarized and published periodically in scientific publications) (5); outbreaks in which the food was eaten outside the United States, even if the illness occurred within the United States; and outbreaks that are traced to water intended for drinking (these are reported to the Waterborne-Disease Outbreak Reporting System). A second limitation is the classification of food vehicles in the surveillance system. Food vehicles can be classified as individual food items (e.g., milk or eggs) or as food categories (e.g., ice cream or multiple vehicles). Therefore, the number of outbreaks attributed to a particular food item might fall under several food vehicle categories. For example, homemade ice cream containing milk and eggs is listed under "ice cream" rather than "milk" or "eggs." The category "Mexican-style food" includes vehicles containing beef, cheese, lettuce, and other ingredients. However, only one food vehicle is identified for each outbreak on the basis of the available epidemiologic and laboratory data. A third limitation is that FBDOs are not included in the surveillance system if the route of transmission from the contaminated food to the infected persons is indirect. For example, in 1988, chitterlings (pig intestines) were the ultimate source of a cluster of Yersinia enterocolitica infections among several infants; however, this outbreak was not included because the infants did not eat the chitterlings (6). A fourth limitation is that no standard criteria exist for classifying a death as being FBDO-related. This determination is made by the reporting agency. How Data Are Presented In this report, 1993-1997 data on foodborne-disease outbreaks are presented as follows:

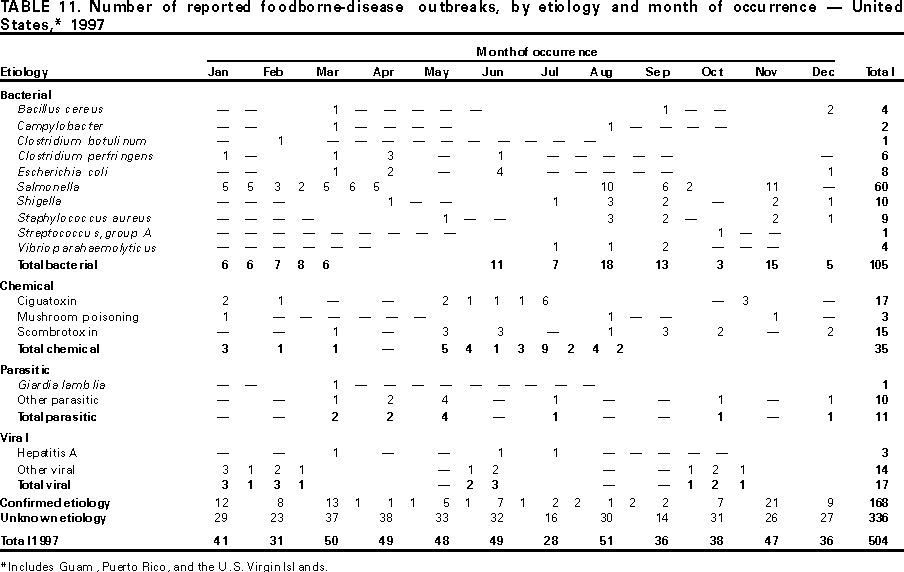

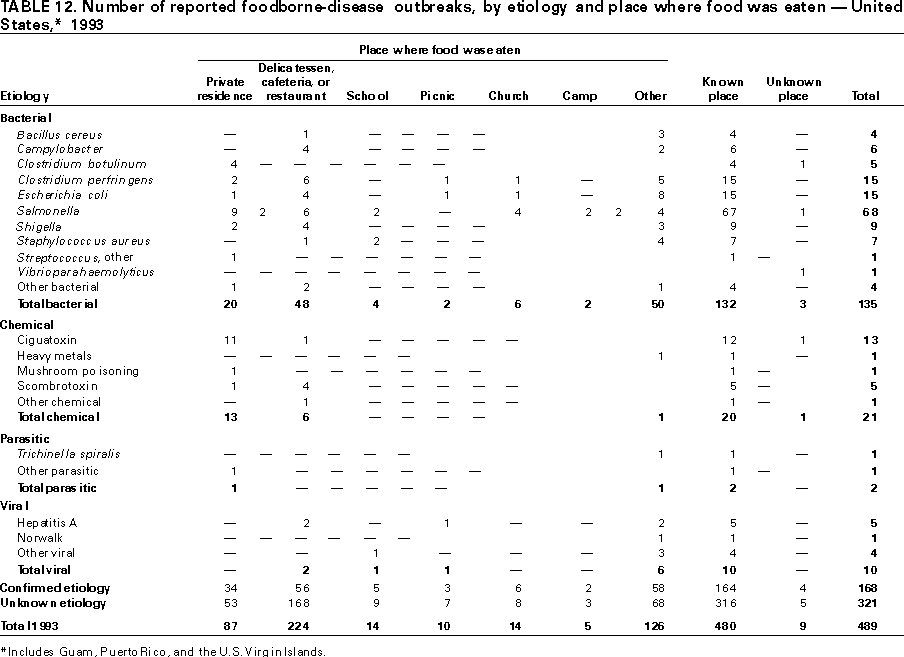

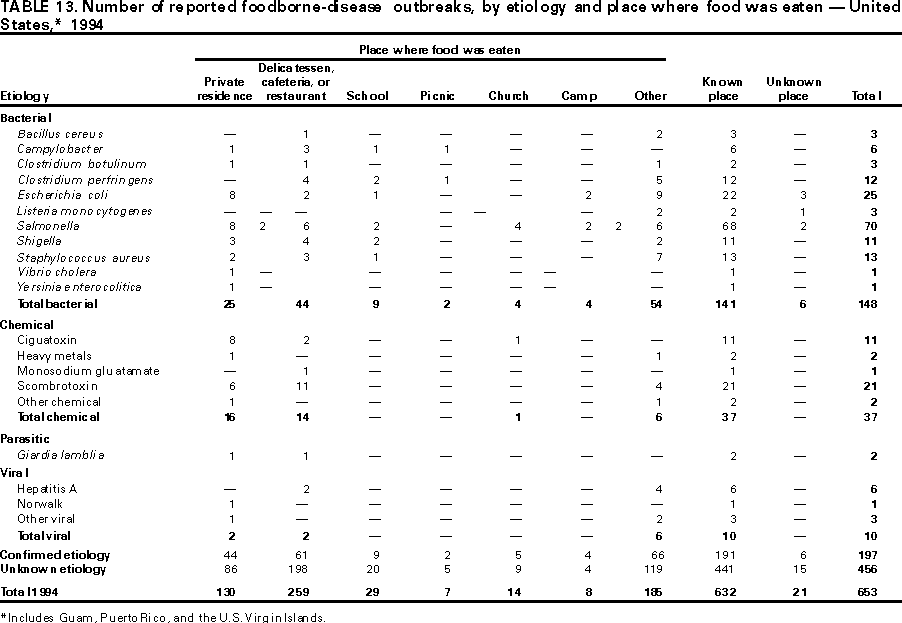

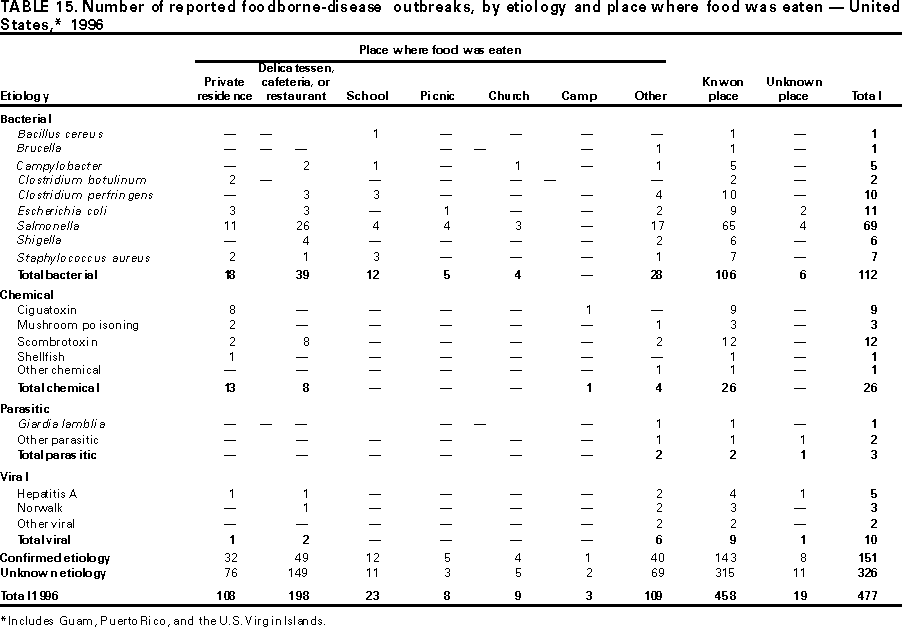

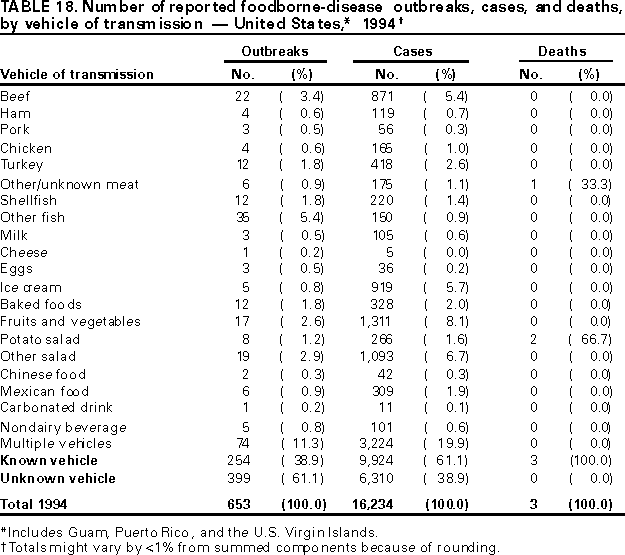

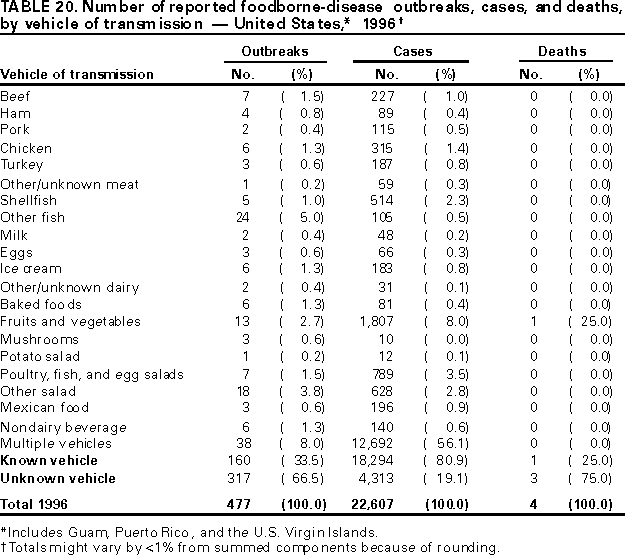

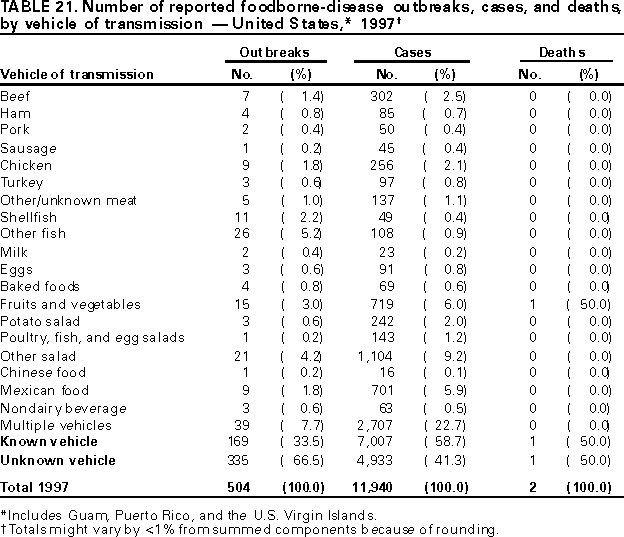

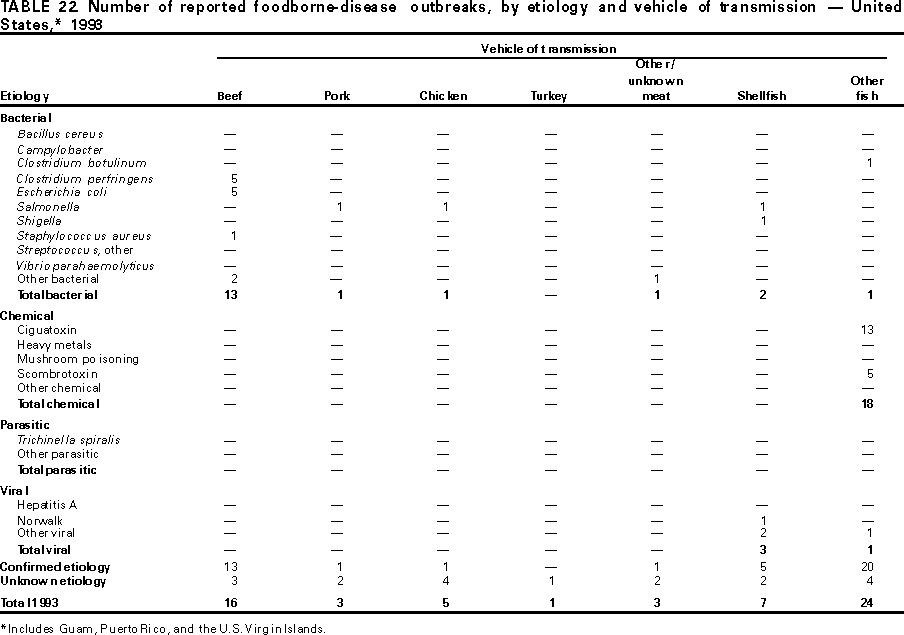

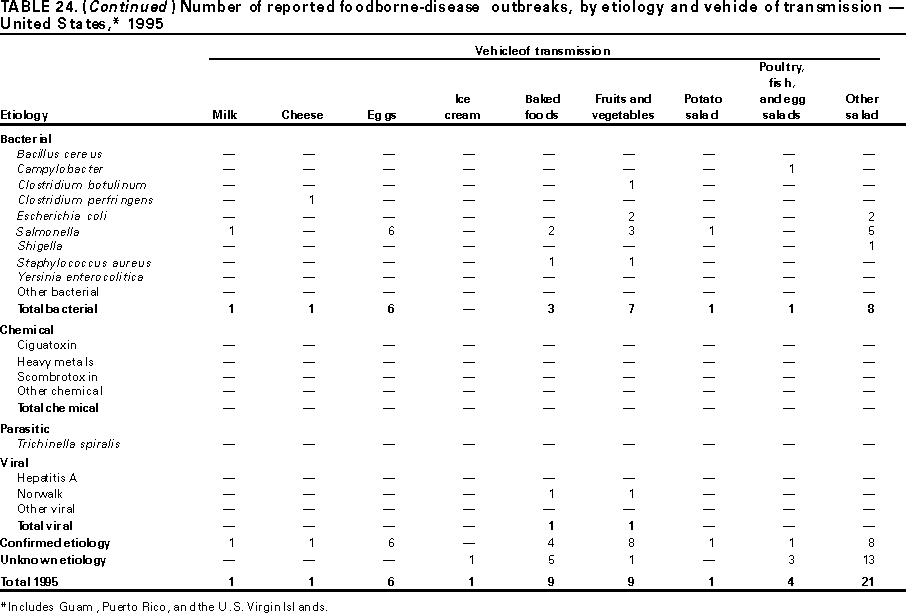

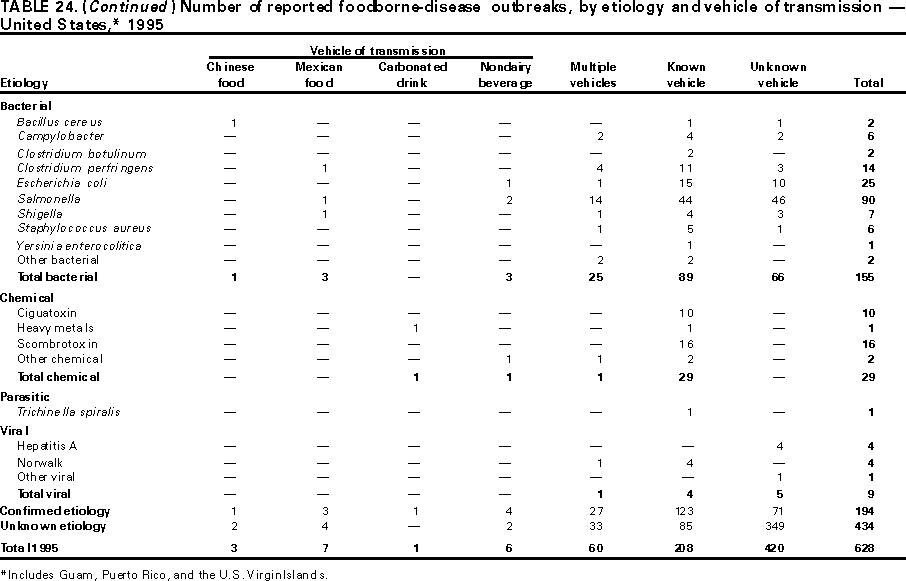

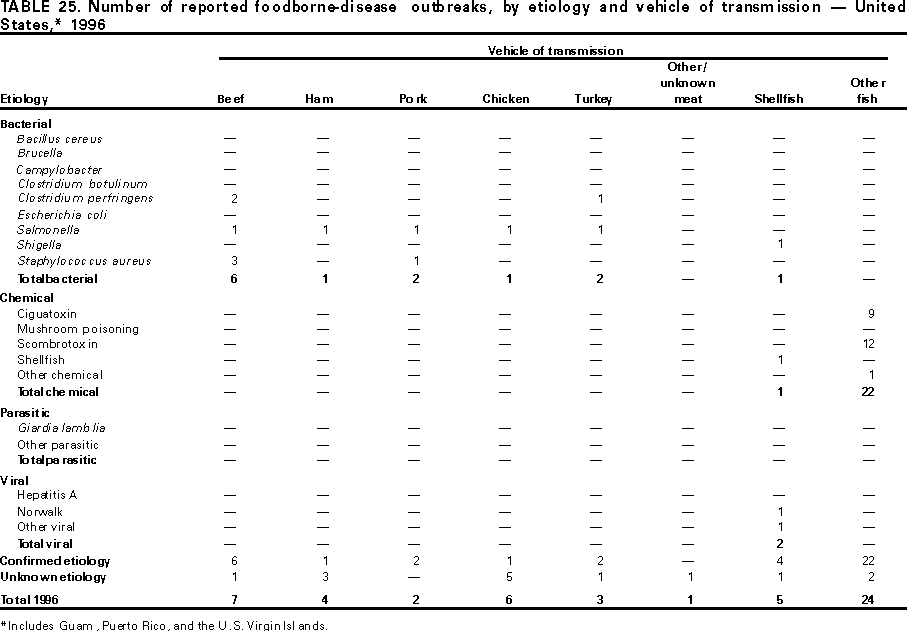

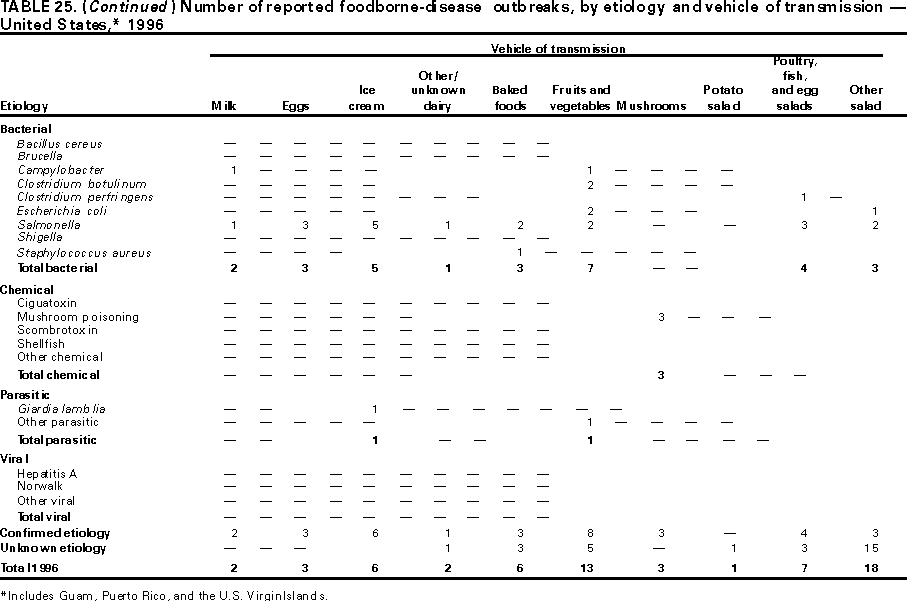

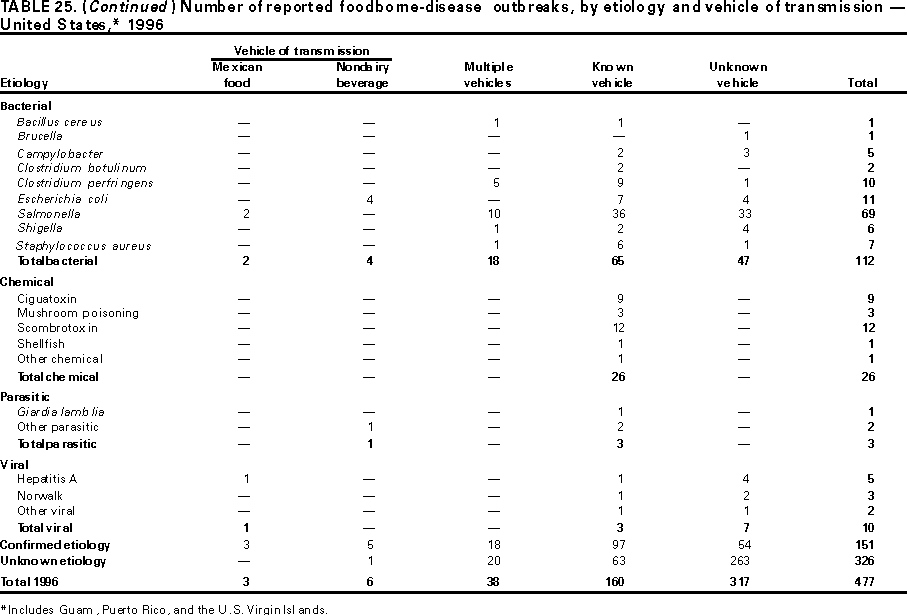

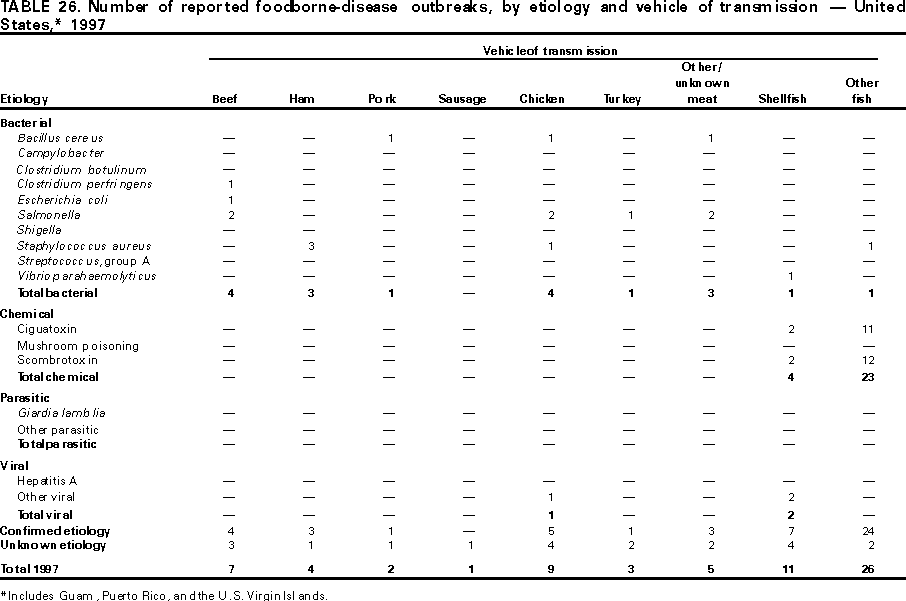

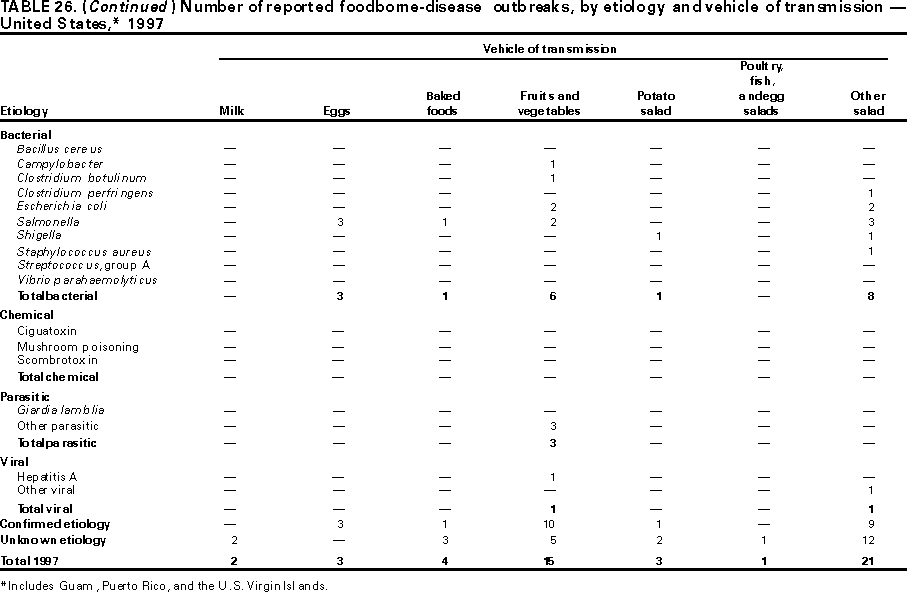

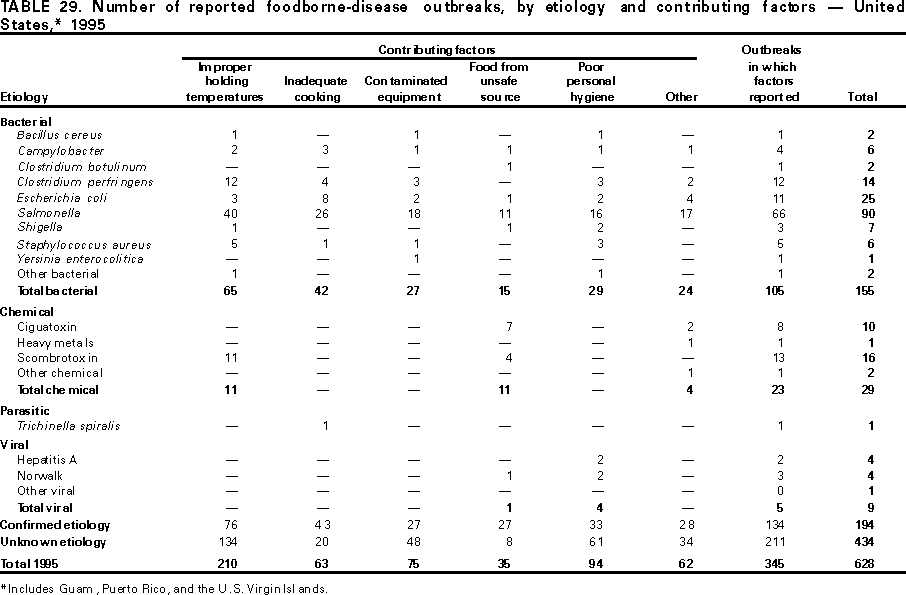

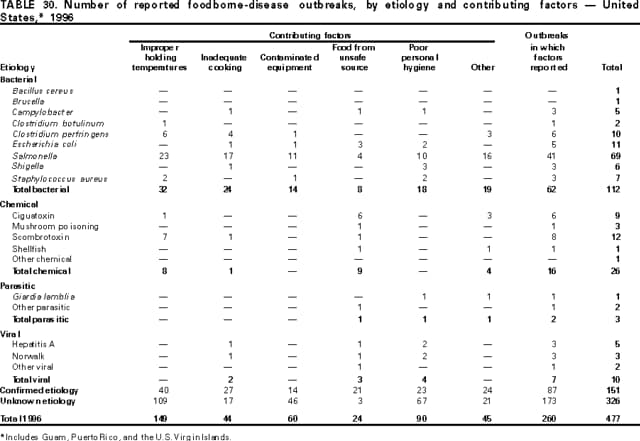

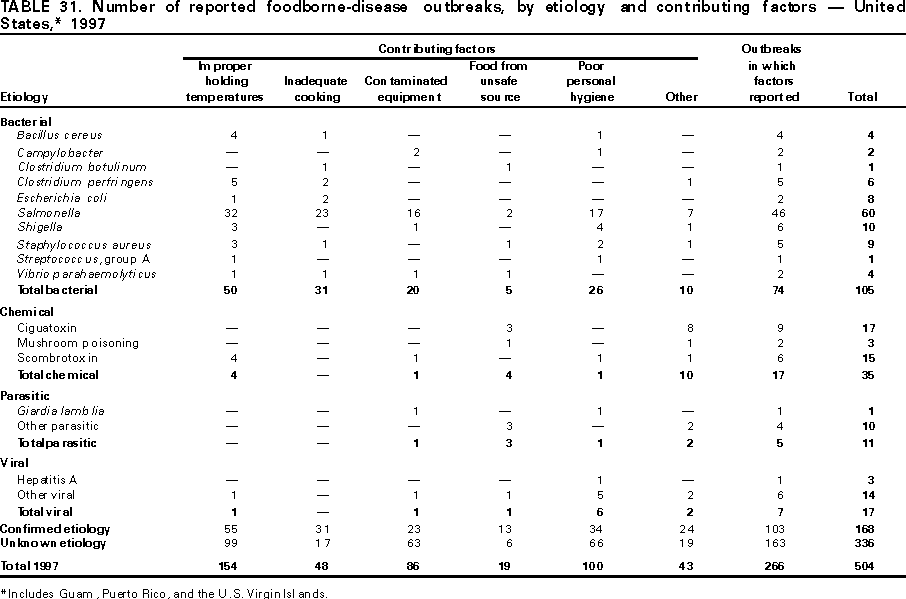

RESULTS From 1993 through 1997, 878 (32%) of the 2,751 outbreaks reported to CDC had a known etiology; these outbreaks accounted for 50,788 (59%) of 86,058 infections (Table 1). Of the 878 outbreaks with a known etiology, 75% (86% of infections) were caused by bacterial pathogens, 17% (1% of infections) by chemical agents, 6% (8% of infections) by viruses, and 2% (5% of infections) by parasites. In most (68%) outbreaks, the etiology was not determined. The incubation period was reported for 1,406 (75%) of the 1,873 outbreaks that had an unknown etiology; in 44 (3%) outbreaks, the incubation period was less than 1 hour; in 428 (30%) outbreaks, 1-7 hours; in 285 (20%) outbreaks, 8-14 hours; and in 649 outbreaks (46%), greater than or equal to 15 hours. Local investigators may report factors they believe contributed to the outbreak. For each of the years from 1993 through 1997, the most commonly reported food preparation practice that contributed to foodborne disease was improper holding temperature; the second most commonly reported practice was inadequate cooking of food (Tables 27-31). Food obtained from an unsafe source was the least commonly reported factor for the 5 years combined. In most outbreaks caused by bacterial pathogens, the food was stored at improper holding temperatures. The annual number of outbreaks reported during 1993-1997 ranged from 477 to 653 (Tables 2-6). These numbers are comparable with those in previous years (3,4). During this period, multistate outbreaks caused by ground beef contaminated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 (7,8) and fresh produce contaminated with Salmonella or E. coli O157:H7 (9) were frequently reported (Tables 22-26). A massive outbreak of Salmonella serotype Enteritidis infections was linked to commercially distributed ice cream made from a liquid premix that had been transported in tanker trucks used previously to haul liquid raw eggs (10). Unexpected vehicles of transmission (e.g., alfalfa sprouts [11], apple cider [12], and orange juice [13]) were also reported. Several outbreaks involved imported food items. Salmonella caused 357 (55%) of the 655 bacterial FBDOs with a known etiology during 1993-1997; 55% of these 357 outbreaks were caused by S. Enteritidis. S. Enteritidis was the most frequently reported cause of FBDOs, accounting for 7% of all outbreaks and 22% of outbreaks for which an etiology was determined. S. Enteritidis also resulted in more deaths than any other pathogen; of the 10 persons who died as a result of S. Enteritidis, four (40%) were residents of nursing homes. DISCUSSION Foodborne-Disease Outbreaks During 1993-1997 As in previous years, bacterial pathogens caused most outbreaks and infections with a known etiology (3,4). However, 68% of reported FBDOs were of unknown etiology, a finding that highlights the need for improved epidemiologic and laboratory investigations. Approximately 50% of these outbreaks had an incubation period of greater than or equal to 15 hours, indicating that many were of viral etiology. Viruses (e.g., Norwalk and Norwalklike viruses) are probably a much more important cause of foodborne disease outbreaks than is currently recognized. Although local and state public health laboratories have often lacked the resources and expertise to diagnose viral pathogens, methods to diagnose these agents are now increasingly available in some state laboratories. Thus, outbreaks of viral etiology might be more likely to be identified and reported in the future. Of the FBDOs with a known etiology, multistate outbreaks caused by contaminated produce and outbreaks caused by E. coli O157:H7 remained prominent. S. Enteritidis continued to be a major cause of illness and death. Approximately 40% of persons who died as a result of S. Enteritidis were residents of nursing homes -- a finding that reflects the seriousness of S. Enteritidis infections in elderly persons, many of whom might be immunocompromised. Persons can decrease their risk for egg associated infections caused by S. Enteritidis by not eating raw or undercooked eggs. Nursing homes, hospitals, and commercial kitchens should use pasteurized egg products for all recipes requiring pooled or lightly cooked eggs (14). Several outbreaks reported during 1993-1997 involved imported food items. This finding demonstrates the role of food production and distribution in FBDOs. Interpretation of Data from the Foodborne-Disease Outbreak Surveillance System Foodborne diseases cause an estimated 76 million illnesses and 5,000 deaths in the United States each year (15). Although foodborne diseases are common, only a fraction of these illnesses are routinely reported to CDC because a complex chain of events must occur before a foodborne infection is reported; a break at any point in the chain will result in a case not being reported. In addition, most reported foodborne illnesses are sporadic in nature; only a small number are identified as being part of an outbreak and thus are reported through the Foodborne-Disease Outbreak Surveillance System. For example, Salmonella infection causes an estimated 1.4 million foodborne illnesses annually (15). However, from 1993 through 1997, a total of 189,304 Salmonella infections (approximately 38,000 annually) were reported through the National Salmonella Surveillance System (16-20), which is a passive, laboratory-based system. In contrast, during the same period, 357 recognized outbreaks of Salmonella infection resulting in 32,610 illnesses were reported through the Foodborne-Disease Outbreak Surveillance System. Thus, the system greatly underestimates the burden of foodborne disease. Moreover, the number of outbreaks summarized in this report represents a small proportion of the outbreaks that actually occurred during the period under surveillance. Most outbreaks are never recognized, and those that are recognized frequently go unreported. The likelihood that an outbreak is brought to the attention of public health authorities depends on many factors, including consumer and physician awareness, interest, and motivation to report the incident as well as the resources and disease surveillance activities of state and local public health and environmental agencies. Outbreaks that are most likely to be brought to the attention of public health authorities include those that are large, interstate, or restaurant associated or that can cause serious illness, hospitalization, or death. Therefore, this report should not be used to draw conclusions about the absolute or relative incidence of foodborne-disease outbreaks related to specific causes. For example, foodborne diseases characterized by short incubation periods (e.g., those caused by a chemical agent or staphylococcal enterotoxin) are more likely to be recognized as common source FBDOs than are diseases with longer incubation periods (e.g., hepatitis A). Outbreaks involving less commonly identified pathogens (e.g., B. cereus, enterotoxigenic E. coli , or Giardia lamblia) are less likely to have a confirmed etiology because these organisms are not always considered in clinical, epidemiologic, and laboratory investigations of FBDOs. FUTURE DIRECTIONS Current methods to detect FBDOs are improving. For example, two new tools that enhance detection of FBDOs are the Salmonella Outbreak Detection Algorithm (SODA) and PulseNet. SODA applies a statistical algorithm to data reported through CDC s National Salmonella Surveillance System to identify significant increases over a historical baseline for any given serotype (21). This technology, now employed at state health departments, can be used to help identify clusters or outbreaks. PulseNet is a national network of public health laboratories that perform pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) on bacteria that might be foodborne (22). The network permits rapid comparison of PFGE patterns through an electronic database at CDC; closely related PFGE patterns suggest a common source. PulseNet is helpful in epidemiologic investigations, particularly those that involve many states. Several changes to improve the ease and timeliness of reporting are occurring. In October 1999, CDC issued a revised FBDO reporting form to simplify reporting by state health departments. In addition, electronic reporting methods such as fax, e-mail, and the Internet are being increasingly used to make reporting more timely. The investigation and reporting of FBDOs by state and local health departments are important steps in efforts to better understand and define the epidemiology of foodborne disease in the United States. At the regional and national levels, surveillance data provide an indication of the etiologic agents, vehicles of transmission, and contributing factors associated with FBDOs and help direct public health actions. References

* Before 1992, three exceptions existed to this definition; only one case of botulism, marine toxin intoxication, or chemical intoxication was required to constitute an FBDO if the etiology was confirmed. The definition was changed in 1992 to require two or more cases to constitute an outbreak. Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top. Figure 3  Return to top. Figure 4  Return to top. Figure 5  Return to top. Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Table 3  Return to top. Table 4  Return to top. Table 5  Return to top. Table 6  Return to top. Table 7  Return to top. Table 8  Return to top. Table 9  Return to top. Table 10  Return to top. Table 11  Return to top. Table 12  Return to top. Table 13  Return to top. Table 14  Return to top. Table 15  Return to top. Table 16  Return to top. Table 17  Return to top. Table 18  Return to top. Table 19  Return to top. Table 20  Return to top. Table 21  Return to top. Table 22    Return to top. Table 23    Return to top. Table 24    Return to top. Table 25    Return to top. Table 26    Return to top. Table 27  Return to top. Table 28  Return to top. Table 29  Return to top. Table 30  Return to top. Table 31  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 3/8/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|