|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

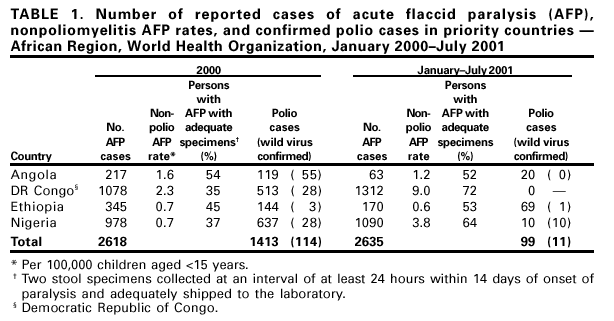

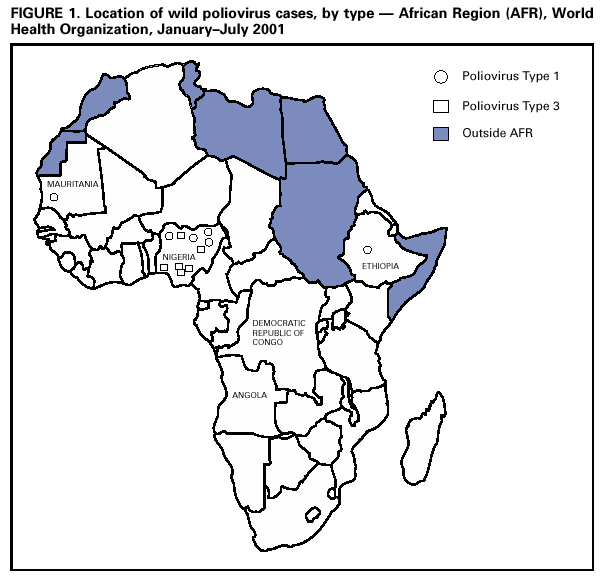

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication --- Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, January 2000--July 2001In 1988, the World Health Assembly, governing body of the World Health Organization (WHO), resolved to eradicate poliomyelitis globally by 2000 (1). In the African Region (AFR), WHO member countries began to implement polio eradication strategies in 1995. Although rapid progress has occurred in much of eastern and southern Africa, wild poliovirus transmission continues to occur in four priority countries: Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Ethiopia, and Nigeria (2). This report summarizes progress toward polio eradication in Angola, DR Congo, Ethiopia, and Nigeria during January 2000--July 2001, and indicates that 11 of 12 cases of wild poliovirus in AFR were identified in these priority countries during January--July 2001 (Figure 1). Routine VaccinationThe four priority countries have reported low rates of routine coverage with three doses of oral polio vaccine (OPV3). In 2000, reported OPV3 coverage among infants was 42% in DR Congo, 42% in Ethiopia, 38% in Nigeria, and 33% in Angola. Supplemental OPV Vaccination ActivitiesSupplemental OPV vaccination activities were conducted in all four priority countries in 2000 and 2001. In Angola, three rounds of national immunization days (NIDs)* were conducted in June, July, and August 2000 with an additional subnational immunization day (SNID)† conducted just before and after NIDs in accessible areas. Access to rebel-controlled areas could not be secured, and approximately 100,000 children aged <5 years did not receive OPV. In DR Congo, three rounds of NIDs were conducted in July, August, and September 2000. A house-to-house strategy was implemented for the first time in one third of the country, excluding some rebel-controlled areas. Similar to Angola, monitoring of NIDs in DR Congo indicated that 3%--10% of houses were not visited, suggesting that children were not reached even in accessible areas. Ethiopia conducted two rounds of SNIDs in March and April 2000 and two rounds of NIDs in November and December 2000. Nigeria conducted four rounds of NIDs in May and June and October and November 2000. During October--November 2000, NIDs in Nigeria were synchronized with those of 15 other countries in west and central Africa with substantial cross-border vaccination activities, high political commitment, and community mobilization (3). NIDs and SNIDs in the four priority countries reported >90% vaccination coverage by round in accessible areas, reaching approximately 73 million children aged <5 years with OPV. In 2001, SNIDs were conducted in Angola and Ethiopia during February--April 2001, using the house-to-house strategy. Three rounds of NIDs were conducted in Nigeria in January, May, and June 2001. The first two rounds of the central African synchronized NIDs were completed in Angola, Gabon, Congo (Brazzaville), and DR Congo during July--August 2001. Preliminary results indicate that approximately 16 million children were vaccinated during synchronized NIDs, including 11,898,767 in DR Congo. Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) SurveillanceThe goal of AFP surveillance is to detect circulating polioviruses and provide data for developing appropriate supplementary vaccination strategies. AFP surveillance is evaluated by two key indicators: sensitivity of reporting (target: nonpolio AFP rate of >1 case per 100,000 children aged <15 years) and completeness of specimen collection (target: two adequate stool specimens§ from >80% of all persons with AFP). From January 2000 through July 2001, the annualized nonpolio AFP rate increased from 0.7 to 3.8 in Nigeria (Table 1). In DR Congo, the annualized nonpolio AFP rate increased from 2.3 in 2000 to 9.0 in 2001 but remained relatively stable in Angola (1.2 in 2001) and Ethiopia (0.6 in 2001). The percentage of adequate stool specimens collected from persons with AFP increased substantially for DR Congo and Nigeria, increased for Ethiopia, and decreased for Angola. In all four priority countries, the percentage of adequate stool specimens remained <80%. The geographic distribution of reported AFP cases is proportionate to population density in Ethiopia and Nigeria but is skewed to accessible areas in Angola and DR Congo. Polio IncidenceDespite surveillance improvements in these countries, no wild poliovirus has been detected in Angola and DR Congo in 2001. Both countries contain inaccessible areas because of civil conflict. Only 10 cases of wild poliovirus have been isolated in Nigeria in 2001. In Ethiopia, wild poliovirus was isolated from a child residing in an area where poliovirus was detected in 1999 and 2000, suggesting that wild poliovirus transmission has continued in 2001. The polio laboratory network for AFR includes 15 national polio laboratories, three of which serve as regional reference laboratories (Central African Republic, Ghana, and South Africa). All stool specimens collected in the four countries are processed in WHO accredited laboratories. Angola is served by the regional laboratory in South Africa. DR Congo, Ethiopia, and Nigeria are served by their national laboratories. As of July 8, 2001, DR Congo, Ethiopia, and Nigeria submitted 4040 stool specimens. Of 3402 specimens with completed test results to date, 2865 (84%) were negative and 382 (11%) contained nonpolio enteroviruses (NPEV). An NPEV rate of 10%--20% indicates good quality of stool condition on arrival in the laboratory. Reported by: Expanded Program on Immunization, World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, Harare, Zimbabwe. Vaccines and Biologicals Dept, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Respiratory and Enteric Viruses Br, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; Vaccine Preventable Disease Eradication Div, National Immunization Program, CDC. Editorial Note:During January--July 2001, only three of 46 countries in AFR (Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Mauritania) reported wild poliovirus isolates; however, Angola and DR Congo contain inaccessible areas because of civil conflict. The incidence of wild poliovirus decreased throughout the region from 61 cases reported in AFR as of August 28, 2000, to 12 cases as of August 28, 2001 (WHO, unpublished data, 2001). These achievements resulted from improvements in surveillance and supplemental immunization activities (SIAs) during the preceding 18 months. Interrupting the remaining chains of wild poliovirus transmission through high-quality SIAs is critical for AFR priority countries during 2001--2002. In Angola, improving SIAs in accessible areas and strengthening the AFP surveillance system will enable identification of areas with poliovirus circulation. The quality and geographic extent of SIAs in Angola need to be improved, especially mapping, marking of houses, record keeping, supervising, using of independent monitors, and social mobilizing. Access to children residing in rebel-controlled areas remains a challenge. In DR Congo, the high AFP rate in 2001 raises a concern of reporting of AFP cases that may not meet the case definition. The NPEV isolation rate of 14.5% for the first half of 2001 suggests that the reverse cold chain that transports these samples to the national laboratory is adequate. In Ethiopia, coordinating surveillance and supplemental OPV vaccination activities with other countries of the Horn of Africa (i.e., Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan) is important because of nomadic border populations. In July 2001, an internal surveillance review recommended targeting Nigerian states with continuing wild poliovirus transmission for conducting mop-up campaigns¶, conducting regular active AFP searches (especially in the riverine areas of the Niger-Delta area), and strengthening project management at national and zonal levels. The substantial progress toward polio eradication in the four AFR priority countries underscores the feasibility of interrupting poliovirus. Future priorities for the region include 1) improving AFP surveillance to allow for better targeting of supplemental vaccination and mop-up activities, 2) reaching previously unvaccinated children and gaining access to all children in the four priority countries, 3) assuring an adequate supply of OPV vaccines for routine and supplemental vaccination activities, and 4) improving basic infrastructure for the Expanded Program on Immunization. Meeting these priorities will require continued external support. References

* Mass campaigns over a period of days to weeks, in which two doses of OPV are administered to all children (usually aged <5 years), regardless of previous vaccination history, with an interval of 4--6 weeks between doses. † Same procedure as NIDS but in a smaller area. § Two stool specimens collected at least 24 hours apart within 14 days from onset of paralysis and shipped adequately to the laboratory. ¶ Intensive house-to-house vaccination with OPV in high-risk districts, conducted in two rounds, 4--6 weeks apart.

Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/28/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/28/2001

|