|

|

Volume 4: No.

4, October 2007

TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

Expanding the Obesity Research Paradigm

to Reach African American Communities

Shiriki K. Kumanyika, PhD, MPH, Melicia C. Whitt-Glover, PhD, Tiffany L. Gary,

PhD, T. Elaine Prewitt, DrPH, Angela M. Odoms-Young, PhD, Joanne Banks-Wallace,

RN, PhD, Bettina M. Beech, DrPH, MPH, Chanita Hughes Halbert, PhD, Njeri Karanja,

PhD, Kristie J. Lancaster, PhD, RD, Carmen D. Samuel-Hodge, PhD

Suggested citation for this article: Kumanyika

SK, Whitt-Glover MC, Gary TL, Prewitt TE, Odoms-Young AM, Banks-Wallace J,

et al. Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Prev Chronic Dis

2007;4(4).

http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/

oct/07_0067.htm.

Accessed [date].

Abstract

Obesity is more prevalent among African Americans and other racial and

ethnic minority populations than among whites. The behaviors that determine weight status are embedded in the core social and cultural processes and environments of day-to-day life in these populations. Therefore, identifying effective, sustainable solutions to obesity requires an ecological model that is inclusive of relevant

contextual variables. Race and ethnicity are potent stratification variables in U.S. society and strongly influence life contexts, including many aspects that relate to eating and physical activity behaviors. This article describes a synthesis initiated by the African American Collaborative Obesity Research Network (AACORN) to build and broaden the obesity research paradigm. The focus is on

African Americans, but the expanded paradigm has broader implications and may apply to other populations of color. The synthesis involves both community and researcher perspectives, drawing on and integrating insights from an expanded set of knowledge domains to promote a deeper understanding of relevant contexts. To augment the traditional, biomedical focus on energy balance, the expanded

paradigm includes insights from family sociology, literature, philosophy, transcultural psychology, marketing, economics, and studies of the built environment. We also emphasize the need for more attention to tensions that may affect African American or other researchers who identify or are identified as members of the communities they study. This expanded paradigm, for which development is

ongoing, poses new challenges for researchers who focus on obesity and obesity-related health disparities but also promises discovery of new directions that can lead to new solutions.

Back to top

Introduction

Obesity is currently viewed as one of the most important health concerns in the United States and is an increasing focus

of federally funded research (1,2). About 30% of Americans are classified as obese. Although overweight and obesity are problems for Americans overall, African Americans and other populations of color are disproportionately affected. Obesity prevalence data for African

American women are especially alarming. Fewer than 20% of black women, compared with 33% of black men, have body weights in the range that is considered healthy (1). Nearly 15% of black women are in the “extremely obese” weight range, characterized by a body mass index greater than 40 kg/m2, equivalent to about 100 lb of excess weight. The prevalence of obesity

among African

American children is notably higher than among white children and has steeper trends (3). One-fourth of African American females aged 6 to 19 years are obese (1). Most African American women are trying to lose weight or control their weight, suggesting that the motivation for weight control is prevalent (4). However, knowledge of effective weight-loss approaches is derived primarily from white

populations (5-7) and relates only to short-term effects. The need to tailor or adapt behavioral weight-loss approaches

for specific populations is recognized, but effective ways to do this with African Americans have not been identified (8-11).

The purpose of this article is to describe a synthesis of efforts to build

and broaden the research paradigm for obesity interventions in African Americans. Although at a basic level obesity results from an energy imbalance,

(i.e., intake of excess calories in relation to caloric expenditure) behaviors such as overeating and physical inactivity that contribute to obesity are shaped by

broader contexts, including social, economic, and political factors, and are embedded in the processes of day-to-day life (12-15). Consequently, research on effective approaches to obesity prevention and treatment must involve examination of complex pathways and ultimately must include identifying means of changing relevant contexts. Reliance on biomedical or individual behavior-change models,

which are less inclusive of social and environmental variables, may limit the ability to identify effective, sustainable solutions. In such models, social contextual variables are often considered only indirectly, as barriers or facilitators to achieving targeted health goals.

Accordingly, identifying approaches to obesity prevention and treatment that are feasible and effective in African American communities requires a focus on life contexts in these communities. Work emanating from fields such as sociology and history has long supported the perspective that social and environmental contexts, particularly in the United States, are strongly defined by race

and ethnicity (16).

Back to top

Synthesis of Broader Perspectives

The synthesis of efforts to build and broaden the research paradigm on obesity interventions in African Americans was initiated by the African American Collaborative Obesity Research Network (AACORN). The synthesis builds on the results of the organization’s first national workshop, held in August 2004 in Atlanta, Georgia, in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity. The Appendix to this article includes a summary of key presentations and related references from the workshop. This workshop was consistent with AACORN’s mission to stimulate research that will enhance the likelihood of effecting permanent solutions to obesity and obesity-related health problems in African American communities and will increase the visibility and agency of African American researchers in obesity research (17). Involving both community and researcher perspectives and drawing on and integrating insights from a broader set of knowledge domains expands the paradigm for obesity research to promote a deeper understanding of the relevant contexts.

In contrast to the typical focus on the health issue of obesity, in which aspects of the social context may be recognized only as they seem to interfere with individual behavioral change, the goal of this workshop was to begin with the social ecology

(i.e., considering first the ways of life, assets, and challenges in African American communities) (18), and then attempting to determine where food, activity, and weight-related variables fit in. We argue that this

procedure may give a more realistic picture of what anchors or motivates weight-related behaviors, what potential pathways

for change are realistic and feasible, and what effective change will require. Although we are motivated by the particularly critical need to address obesity in African American communities, we believe that progression toward such an expanded paradigm may be needed in other ethnic minority populations, both generally and in relation to obesity.

Back to top

Reframing and Expanding the Research Paradigm: Concepts and Process

AACORN has articulated priority research recommendations (17) related to designing and conducting more contextually relevant and effective obesity prevention and treatment interventions. These research recommendations build on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) obesity research agenda (2,19), provide rationale and directions related

specifically to African American communities, and include several

recommendations that may improve the relevance of research on obesity prevention and treatment interventions by including the contextual variables of African American community and family

life (17):

- Better characterize perceptions of food, eating, physical activity, and weight and their roles in African American family and community life.

- Determine the extent to which food, activity, and weight-related market behaviors of African Americans are influenced by targeted marketing and local availability of foods and how perceptions of buying power shape food choices.

- Obtain a better understanding of the processes whereby African American communities undergo cultural and structural changes and the key determinants of these processes.

- Design and evaluate weight-loss and weight-control strategies geared to African American families, social settings, and social dynamics.

- Increase qualitative and community-based research with African American communities to elicit underlying perceptions, issues, and priorities to derive insights for measurement and program design and to promote sustainability.

- Increase the number of African American researchers involved in obesity research, including researchers from disciplines such as family studies, child development, urban planning, and social work.

- Convene an ongoing, multidisciplinary group of experts, e.g., from health, education, human development, marketing, humanities, social science, economics, and urban planning, to develop comprehensive obesity research initiatives with African American communities.

These recommendations call for an increased emphasis on qualitative research and community-based participatory research (CBPR) and also for involving experts from a more diverse set of disciplines

who can shed light on the “lifeworlds” of African Americans and provide a better sense of the community processes that need to be included in any framework for interventions. Lifeworld

is a concept that emphasizes

. . . the centrality of perception for human experience. This experience is multi-dimensional and includes the experience of individual things and their contextual/perceptual fields, the embodied nature of perceiving consciousness, and the intersubjective nature of the world as it is perceived, especially our knowledge of other subjects, their actions and shared cultural structures (20).

Consistent with the perspective described above, the paradigm expansion was guided by questions such as

- Who can help us understand the deeper aspects of cultural and psychosocial processes that may influence the relationships of African American women to food?

- Who are the scholars who study aspects of day-to-day life in African American communities?

- What disciplines do these scholars represent?

- Do they consider food and health issues in their work?

- How might their research approaches and methodologies differ from those typical in the obesity research field?

- How can we access and integrate the knowledge and experience from these other fields?

We also asked ourselves

- How do obesity research issues look from inside African American communities?

- What approaches can university researchers take to render research as relevant and effective as possible?

- How do approaches taken by African American researchers differ from those taken by other researchers?

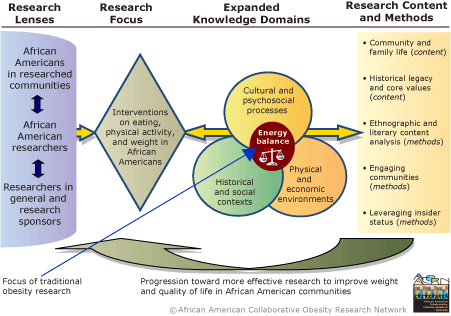

The Figure describes the conceptualization and process involved in expanding the paradigm for obesity research with reference to African Americans. As the Figure illustrates, considerations related to the design and implementation of obesity-related interventions are viewed through three different lenses or perspectives: 1) those of African Americans in the communities of interest for research; 2) those of African American researchers; and 3) those of the research community in general, which also reflect the perspectives of research funders. Incorporating the views of

community partners about obesity research and engaging community members through academic–community research partnerships is essential to this expanded paradigm. The perspectives of African American researchers are shown as interacting with community perspectives and linked to, but also distinct in some ways from, those of researchers in general (i.e., researchers who are not also members of the African American community). This emphasizes the importance of recognizing the dual perspectives that may apply when researchers are members (with respect to ethnic identity and shared

history and experiences) of the communities they study and at the same time members of the academic community and accountable to research funders. While these dual perspectives play out for most researchers, many African American researchers, for the historical and sociopolitical reasons explained below, have to resolve intense social dichotomies inherent in this duality.

Figure: AACORN’s Expanded Obesity Research Paradigm. [A text description of this figure is also available.]

Reprinted with permission of the African American Collaborative

Obesity Research Network.

This paradigm expansion is based on the premise that the behaviors that determine weight status are embedded in the core social and cultural processes and environments of day-to-day life.

Therefore, identifying effective solutions to obesity requires an ecological

model that is inclusive of relevant contextual variables, which include

variables influenced by race, ethnicity, and social position. Center: The traditional focus on caloric intake and output is depicted in the intersection of knowledge domains potentially informative for developing interventions on eating, physical activity, and weight. This representation conveys the utility of factoring in knowledge of historical and social contexts, cultural and psychosocial processes, and the

physical and economic environments that influence preferences, perceived and actual choices related to food and activity, and the relative ease or difficulty of exercising these choices. Such knowledge is fundamental to understanding the perspectives and day to day experiences that are the backdrop for weight control efforts. Accessing relevant knowledge from these expanded domains is enhanced by

interactions with scholars in fields such as family sociology, literature, philosophy, transcultural psychology, economics, marketing, and urban planning. Left: What is seen, asked, and heard depends on who is looking and listening. Important eyes and ears for understanding weight issues include those of lay members of the communities of interest (e.g., African Americans in

researched communities) and researchers in relevant fields whose expertise incorporates insights based on lived experiences and shared identity with the community of interest (e.g., African American researchers in nutrition, physical activity, public health, and other areas), in addition to other researchers with relevant interests and expertise, and research sponsors. Right: Content and methodological themes emanating from this inclusive, integrative paradigm applied to African Americans highlight 1) the importance of considering family and community interactions related to food acquisition, food- and activity-related social interactions, the structure and organization of community processes, women’s roles, and differences by generation, social position, and

other demographic variables; 2) the potential influence of the collective historical legacy of slavery and its derivatives on core values such as trust and loyalty and on interactions with the health care system, media, and other social institutions; 3) the potential value of qualitative investigations that include direct observations, eliciting and analyzing narratives, and exploring the content

of literary expressions to yield different or richer insights than obtained from more typical biomedical approaches; 4) the essential need to fully incorporate the views, expertise, and agency of community partners in the research process; and 5) the potential benefits and challenges of encouraging African American researchers to leverage their insider status in ways that benefit the communities

they study, the research endeavor, and their own academic careers.

As shown in the Figure, at the center of the process of expanding the research paradigm is the traditional focus on energy balance and weight control at the intersection of three knowledge domains that relate to African American communities (“expanded knowledge domains”). Historical and social contexts and cultural and psychosocial processes are fundamental aspects of African American lifeworlds as are physical and economic environments. The elements within each domain correspond to topics from family sociology,

literature, philosophy, transcultural psychology, marketing, economics, and studies of the built environment (Appendix). Reflections on these knowledge domains from the three different perspectives (“research lenses”) yield five interrelated themes that pertain to research content and methods. Content themes relate to the importance of community and family life and of the historical legacy and core values that shape the context for research in African American communities. Method themes relate to the potential value of qualitative approaches, such as ethnography and content analysis of literary works; engaging communities; and the ability of African American researchers to leverage their insider status in ways that benefit the research endeavor. Explanation of these themes is the main thrust of this article. The

Table lists the subthemes identified within each theme. Cross-references to presentations in the Appendix are included, where applicable, to provide links to relevant references.

Back to top

Community and Family Life

Four subthemes emerged on community and family life contexts for obesity research (See summaries

in Appendix for Robin Jarrett, Beverly Guy Sheftall, and Jerome Williams.)

Community-specific environmental influences

African Americans are racially segregated and, as a population, are less likely than whites to live in physical environments that support healthful eating and physical activity. One quarter (24.7%) of African Americans live below the poverty line, and another 24% have incomes between 100% and 200% of the poverty line (21). The comparable figures for non-Hispanic whites are 8.6% and 15%. Hence, economic constraints on both food choices and opportunities for physically active recreation are disproportionate. Media

and other marketing channels directed at African Americans facilitate the targeted advertising of products that are conducive to obesity (e.g., high-fat, low-nutrient foods). Yet these same channels can function as pathways for community-based interventions. Taken together, these environmental forces suggest above-average difficulty for African American adults in following recommendations for weight control for themselves or their children.

Community structure and organization

Communities are complex systems with some layers that may not be visible

to outsiders. Learning how communities are organized and how they operate

may increase the ability to take a holistic or integrated approach to the

design of programs to address food, activity, and weight. For example, how do families

in low-income African American communities obtain their resources, and do they share them? What is the effective household income in an intergenerational household? What are the informal social

networks that provide norm-setting, assistance, and support to people in the community? How do people take care of each other in times of difficulty, especially where major life challenges are constant phenomena?

Another aspect of structure and organization relates to temporal and spatial variation in how people interact within a neighborhood. Who controls what spaces? Is the same place or route safe at some times during the day but not at others? Ethnography suggests that identifying such sources of variation and understanding how people interact will give a different picture of life in communities than one

would obtain

on the basis of survey measures typically used to describe communities for comparative reasons.

Women as a central focus

The high prevalence and severity of obesity among black women strongly influence the context for addressing obesity in African American communities. Many black women are heads of households. They have respected and influential roles in extended families, religious and civic organizations, and in other types of social networks, and they control most food shopping and preparation. Certain food-related roles may be integral to black women’s positions of influence in their communities. Use of food as a mechanism to cope with stresses

related to poverty, sexual abuse, violence, and racial discrimination is relatively more adaptive than coping through the use of alcohol or drugs as palliatives (22). Having a large body size may have adaptive elements as well

(i.e., convey strength and power and offer protection from domestic and street violence).

Researchers designing interventions to change eating behaviors or weight must be cognizant of the possibility that long-term changes in community perspectives related to food and weight could alter other aspects of the social ecology. In this sense it is impractical to design interventions on overweight or obesity that are incongruent with black women’s needs and perspectives. Interventions may first need to address alternative ways to meet needs and evolve different or expanded perspectives on food, activity, and weight issues.

Heterogeneity

The common misperception of African Americans or African American communities as homogeneous ignores within-group diversity. African Americans share common experiences in certain critical ways (e.g., the ongoing reality of racial discrimination, the history of slavery and related psychosocial and cultural legacies

for the majority who are U.S.-born). Yet, the heterogeneity in African American communities also

should be emphasized, for example, in differences in socioeconomic status, family types, neighborhood characteristics, and in

urban versus rural areas and regions of the country; and diversity in values and psychosocial perspectives. Effects of socioeconomic status on obesity in African Americans are not always predictable based on patterns observed in whites. Aspects of being African American that are relatively independent of socioeconomic status may also influence obesity and related health problems.

Back to top

Historical Legacy and Core Values

The slave trade that brought people of African descent to the United States and its related history of inhumane treatment, coupled with contemporary circumstances of African Americans that evolved from this legacy, shape core values and norms within African American culture and deep psychosocial perspectives in African American communities. The following two subthemes require consideration. (See summaries

in Appendix for Howard McGary and Linda James Meyers.)

Historical importance of trust

Researchers should go far beyond the philosophical perspectives of trust in human relations to fully understand the concepts of trust and distrust in the setting of health disparities research and why it is so important to establish, gain, and maintain trust when working in African American communities. Survival during slavery, and especially during attempts to gain freedom, was highly dependent on blind trust and loyalty within networks and was coupled with ingrained distrust for anyone identified as benefiting from or maintaining

slavery. This instinctive reliance on trust and distrust in guiding actions and alliances was reinforced during the 20th century civil rights struggle. It continues to be reinforced by various sociopolitical events and circumstances reflective of institutionalized racism, and it influences interactions of African Americans with the society at large. To permanently dispel distrust of health care institutions or their personnel among African Americans, for example, and to remedy the harm that can result from it will require that several generations of Americans fully

embrace the principle that all people are, indeed, created equal — in other words, a major social change in the way that American society views its responsibilities to all citizens. Community-partnered research on obesity or other health issues can actually help to foster such social change. In any case, relying on superficial approaches or not understanding the reciprocal and long-term loyalty dimensions that come with gaining trust will be counterproductive.

Collective trauma

The legacy of slavery and prolonged exposure to various forms of sustained socioeconomic and sociopolitical distress also has imposed intergenerational psychological consequences in the form of post-traumatic stress. This is analogous in concept to the legacy attributed to the Holocaust among Jews. The callous denial of humanity during slavery constitutes a collective trauma that has created a permanent yearning for a meaningful sociocultural grounding for African Americans. There are diverse individual experiences with, and expressions of,

this need for grounding, both within and across generations. Individuals have different sensitivities to this trauma and a wide variety of ways of coping with it. The impact of this historical legacy on the collective of the African American community, therefore, varies with time, context, and situation.

Creative approaches are needed to uncover how these deeper issues of historical trauma can fit with the need for health promotion in African Americans generally and for weight control specifically. The continuing exposure to race-related adverse experiences influences the priority given to

other aspects of the lifeworld. Combined with the effects of past and current exposure to material deprivation, community norms may condone behaviors such as overeating as acceptable coping strategies in spite of the

effects on body weight. Collectively, African Americans’ social concerns

clearly supersede weight-related concerns, although weight-related concerns may add to the burden.

Back to top

Ethnography and Literary Content Analysis

Even well-validated survey instruments are often based on a general, superficial understanding of salient issues. That is, they may measure something well, but that “something” must always fit into preconceptualized pigeonholes. Particularly when

used to study traditionally disenfranchised populations whose perspectives are not usually sought, naturalistic research methods can help researchers to gain insights that can only be obtained by “hearing the voices” of people inside these communities. Qualitative research requires personal commitment, lifetime involvement,

and skills from the researcher that differ from those for quantitative research.

Two subthemes related to learning to hear the voices are the potential value of ethnography and

the analysis of literary works.

(See summaries for Robin Jarrett and Beverly Guy Sheftall in the Appendix.)

Ethnographic research methods

Ethnography allows extended and repeated observations of people in their day-to-day life contexts and deepens the understanding of communities and their members (23). Ethnography can “unpack” the perceptions of reality by the groups under study and create a canvas of relevant information to guide intervention. Relevant to obesity, ethnography can identify unrecognized facets of community life that relate to eating, activity, and weight control.

Literary representations of African American life

Content analysis of African American literary works to understand relevant issues in context is an unused or underused option for learning more about life in African American communities and understanding where and how food and weight issues fit in. Referring to works of African American writers or film producers, for example, takes advantage of the insights of these artists in identifying truths that reflect variations on the collective, lived experiences of African Americans. In addition to the potential value of

this approach for gaining a better understanding of the context for weight-related interventions, literary works, film, and television productions may also provide innovative vehicles for interventions

(i.e., health promotion messages could be incorporated into these works).

Back to top

Engaging Communities

The research lenses in the Figure remind us of the differences in research perspectives of community members and academic researchers and of the need for CBPR to integrate and balance these perspectives (24). Although the importance of genuine CBPR approaches is clear,

the potential benefits of CBPR to communities and their members may be compromised by unintended consequences of poor implementation, which means that the research itself may also be compromised (25). It is essential to clarify how best to achieve community involvement in a manner that is mutually satisfactory and

beneficial to community and academic partners. This means, foremost, the creation of trust and of a social contract of long-term loyalty. It implies explicit steps for creating opportunities for communities to discuss their perceptions of health problems, what resources they have, what priorities they set, and to determine their sense of what approaches have the potential to remedy problems.

The differences in perspective, the social distance, and the power inequity between academic researchers and community-based research partners are major hindrances to increasing mutual trust and respect (25). Community-based research partners are in a relatively weak position with respect to obtaining funding directly, which renders them dependent on and subordinate to universities, which further complicates their relationship with academic researchers.

(See summaries in Appendix for Margaret Grayson and Anna Huff, Robin Jarrett, Howard McGary, and Linda James Meyers.)

Community members as equal research partners

Academic institutions and researchers have traditionally viewed researched communities as “subjects”

(i.e., people and settings that researchers can probe and rectify with their expertise). It is difficult to change this cultural lens of the professional researcher; a new lens is needed. Researchers must view community partners as equals who bring vital and different knowledge and expertise to the research process. Without this view, changes in interactions with community partners may be implemented on the surface but not

carried through on other levels (e.g., related to decision making and sharing of resources), even by those who are well-intended and who embrace, intellectually, the need for

CBPR. Insufficient commitment to this aspect of equity will create a backlash because of the aforementioned problems of trust and distrust. Learning and training should be bidirectional between academic researchers and community partners and

should involve a commitment to hearing and speaking truth from both directions.

Community strengths

Partnering with community members and organizations helps academicians to learn from community members’ knowledge and experience. Partnering will also identify strengths and opportunities often overlooked that can be leveraged for health improvement. Communities that survive under difficult economic and sociopolitical conditions have, by definition, developed ways to work around or remove barriers and live with or solve complex problems. The survival skills of community members, when properly understood, may also be potential assets that can

facilitate both participation in health research and improvements in community health. Health research participation and improved community health can, in turn, add to community capacity and community strengths.

Increase direct benefits to researched communities

Communities

benefit more from research if resources are shared, thereby avoiding duplication

and the attendant potential for excessive burden, and also facilitating

synergistic effects among projects and over time. Our paradigm fosters

coordination among researchers studying the same communities and feedback to

communities about the results of research conducted in their or similar

communities.

Back to top

Leveraging Insider Status

The research lenses in the Figure highlight the dual perspectives that may occur when African American researchers identify or are identified as members of the communities they study while they also maintain allegiance and accountability to the academic research enterprise. African Americans are connected by a shared social history. Researchers function in a professional context and culture. Hence, this dual perspective is unavoidable. When the duality relates to an ethnic identity that is associated with a long history of denigration, abuse, and denial

of humanity, it becomes potentially distressing. Even when African American researchers who, for reasons of social class or lived experience, do not identify personally with African American research participants, they may nevertheless be viewed as “one of us” by study participants or community members because they are African American. This scenario creates subtle and not so subtle challenges, both in the academic community and in the ethnic community (26). There are several important, interrelated subthemes:

Establishing trust and credibility

Insider status may create the potential for greater rapport and trust, but this is not automatic. African American health professionals and researchers may encounter distrust or low credibility if they fail to acknowledge their commonality with some of the same issues faced by the people from the community. Finding an effective social distance or posture may be difficult, and what is effective in this respect may change over the course of relationships with communities. On the other hand, appearing to overidentify (i.e., with one’s

ethnic community) may lead to alienation from peers in the scientific community and role confusion for the researcher. African American researchers conducting research with African American communities may have an almost daily dilemma in how to find and maintain trust and credibility in both worlds.

Connections to communities of reference

Research in African American communities that is conducted by African Americans will still involve cross-cultural relationships in certain respects

(i.e., professional perspective, social class, or other experience-based variables). Cross-cultural relations require constant attention to the double lenses that are used and take a long time to fit comfortably (27). In principle, in using CBPR, the connection with the community becomes open-ended and will flow from research to service, to advocacy, back to

research, to social relations, and then to more research. For many African American and other ethnic minority researchers, retaining ongoing, close, personal connections with communities of reference may be critical to assessing and enhancing insider knowledge and evaluating the validity of professional perspectives. This

process also provides opportunities to reciprocate with community service, where that is desirable, and to renew the motivation to make the effort needed to conduct research under complex and difficult circumstances. However, remaining connected also means

continuing to experience — at least through empathy — the problems one is trying to address or to work around. Conducting research as an insider is, therefore, also potentially more stressful than when one can maintain an outsider perspective. One may hear the voices long after the data have been analyzed and the paper published.

Objectivity and expectations

Researchers who have advocacy goals or insider perspectives may feel, and perhaps want, to be personally involved with and affected by the research participants and the subject matter. This

desire for personal involvement goes against the grain of the prevailing biomedical paradigm, which stresses maximum objectivity of researchers and in which a relatively detached stance toward research participants is the norm. In addition, identification with the researched community or being identified by the community as an advocate may also create demands (external or self-imposed)

to ensure that the community benefits in some immediate way from providing access and participation. The business of research has potentially exploitative elements. The desire or obligation to give back to the community may be a major consideration for some researchers but may not be highly valued or rewarded by the academic institution sponsoring the research.

Strong tensions develop between institutional demands or practices and a researcher’s commitment to the well-being of the community in which the research is focused or based, although this

tension varies among institutions. The greatest problems may arise when the institution in question is located in or very close to the communities where the research takes place and where historic academic–community relationships have been difficult, as is

true for many U.S. academic medical centers. Nevertheless, the desire to see communities benefit is a legitimate and ethical consideration for how researchers interact with communities and how they view the balance of benefits to communities and institutions. Ideally, researchers can provide service to the

communities in ways that also stimulate and sustain community members’ interest in, and capacity for, participation in health research.

Finding social and professional support

Researchers as well as mentors and colleagues should acknowledge the psychological and social demands associated with functioning in a combined insider–outsider role and should appreciate the potentially above-average or qualitatively different needs for supportive environments. Both the time and the opportunities to obtain appropriate and adequate support are needed.

Back to top

Implications

No consensus exists on how to improve obesity research in communities of color (8-10). (See

summary in Appendix for Shiriki Kumanyika.) Various types of cultural adaptations have been

used in studies with African Americans: limiting the audience (inviting only African Americans to participate); matching staff ethnicity by hiring only African American staff; including content designed to appeal to the perceived sociocultural perspectives of African American audiences;

and including community members in the conceptualization and development of program content and format and to access

traditions, views, norms, core values, and language or culturally influenced perspectives (8,9).

These types of adaptations apparently do not confer a dramatic

advantage in the ability of African Americans to lose weight (8). Many

approaches used are intuitively appealing and theoretically based to some extent

(8,9), but culturally adapted programs have often yielded disappointing results. Weight losses reported in published studies of programs that include such

adaptations have often been negligible or very small, and retention rates are

not necessarily better than in other programs (8,10). The reasons for low

success rates in studies of culturally adapted programs — in which success is

judged on the basis of attained weight loss — may be explained by structural

differences between these types of studies and clinical studies of efficacy that

yield more impressive weight losses. Culturally adapted programs differ from

efficacy trials in that their settings are less amenable to control by the

researcher; their duration is often shorter; the study populations are more heterogeneous and less likely to have been selected on the basis of their ability to adhere to the program; behavior change approaches are less strict and are designed to be

more responsive to participant needs and interests; and the staff are less likely to be highly trained specialists. Although these characteristics often render culturally adapted programs more relevant to and representative of the community of interest and more feasible for dissemination, they also tend to reduce the strength or effective dose of the weight-loss counseling delivered.

On the other hand, the possibility that other important outcomes are positively affected by such programs should be considered. Weight control programs touch upon many aspects of people’s lives other than specific eating and physical activity behaviors. For example, behavior-change counseling may target various cognitive processes, coping strategies, stress management, social skills, and personal administrative skills, such as time management, priority setting, and problem solving, and may encourage self-reflection and building of self-confidence. Benefits in these areas

may occur whether or not the weight-loss goal is achieved during the applicable follow-up period and could ultimately have positive implications for the health or quality of life of participants. Assessing such benefits could provide important insights about the dynamics of culturally adapted programs.

Particularly pertinent is our assessment that the emphasis on culture in studies conducted to date has been relatively narrow and has focused on sociocultural attitudes and beliefs about food or physical activity or on changing the intervention setting without attention to the more fundamental social context issues we have explored here. We have identified few whole-community or comprehensive studies relevant to obesity prevention or control (11). As we have discussed, individual behavior issues related to eating and physical activity are intertwined with social,

physical, economic, and policy environments. Some very fundamental and structural aspects of the environments of African American life are biased toward unhealthy dietary patterns and physical inactivity (28,29). (See presentations by Jerome Williams, Adam Drewnowski, and Kristie Lancaster and Melicia Whitt-Glover

in Appendix.) Weight gain may be incidental to coping strategies such as an overreliance on food to manage emotions, cope with stress, or reward children, combined with reliance on television watching for recreation and

to keep children engaged because it is affordable and safe. Individually oriented interventions that address cultural attitudes and beliefs out of context will be insufficient to alter patterns of day-to-day living that are conditioned responses to environmental circumstances. In fact, the entire approach to adapting obesity prevention interventions to the “culture” of African American communities should be reexamined and reframed

to be consistent with the expanded paradigm proposed here, that is, based on an ecological model that leads to environmental and policy approaches

and also addresses relevant themes in family and community life.

Back to top

Conclusion

AACORN’s 2004 workshop initiated a process of “out-of-the-box” thinking about how to frame and study obesity issues in African American communities. The themes

identified from this process add structure and detail to the previously developed AACORN research agenda (17), particularly with respect to the importance of multidisciplinary expertise, qualitative research, and

high-quality CBPR. The results of this synthesis suggest the type of research that the authors, as African American scholars in fields related to nutrition, physical activity, and obesity, feel especially suited to pursue given our lived experiences and accumulated knowledge. The expanded paradigm highlights the need for African American researchers to become more numerous, effective, and

acknowledged in the obesity research field. However, it also highlights the challenges faced by researchers who are linked, through ethnic identity and shared experiences, to the communities they study while also functioning in academic contexts that may not value either the communities or community-based research.

The expanded paradigm described here suggests that weight-control interventions must be framed more holistically to consider other relevant social and health priorities and to allow for the possibility that excess weight is part of a complex set of adaptations to adverse life circumstances (30). This paradigm, for which development will be ongoing, means new challenges for researchers who

focus on obesity and obesity-related health disparities and promises discovery of new directions that can lead to new solutions. We are convinced of the potential value of casting the net widely to identify and work with disciplines and scholars who can contribute to this line of research. Along these lines, the second national AACORN workshop held in August 2006 further explored

some of the themes discussed here in a dialogue with researchers and community partners whose work addresses critical contextual issues such as violence prevention, high prevalence of incarceration, housing needs, and environmental justice issues (31).

Back to top

Acknowledgments

Dr Kumanyika and AACORN are supported in part by the University of Pennsylvania-Cheyney University of Pennsylvania NCHMD EXPORT Center for Inner City Health, funded under grant P60 MD000209 from the National Institutes of Health. AACORN is also supported by a planning grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors are indebted to Dr William Dietz, Ms

Annie Carr, and Ms Refilwe Moeti of the Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the sponsorship and logistical support for the AACORN 2004 workshop. We are deeply appreciative of the participation of approximately 60 colleagues in this workshop and particularly to the invited speakers, Dr Adam Drewnowski, Ms Margaret Grayson, Ms

Anna Huff, Dr Robin

Jarrett, Dr Howard McGary, Dr Linda James Myers, Dr Beverly Guy Sheftall, and Dr

Jerome Williams, for sharing their insights and experiences during the

deliberations (Appendix notes speaker affiliations). We thank Edmund

Weisberg for editorial assistance and Dr Christiaan Morssink for his substantive guidance on revisions of the manuscript.

Back to top

Author Information

Corresponding Author: Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, MPH, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, CCEB, 8th Floor Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Dr, Philadelphia PA 19104-6021. Telephone: 215-898-2629. E-mail: skumanyi@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Author Affiliations: Melicia C. Whitt-Glover, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Winston–Salem,

North Carolina; Tiffany L. Gary, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore,

Maryland; T. Elaine Prewitt, Department of Health Policy and Management, Fay W. Boozman College of

Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock,

Arkansas; Angela M. Odoms-Young, Public Health and Health Education, School of Allied Health, College of Health and Human Sciences, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb,

Illinois; Joanne Banks-Wallace, School of Nursing and Program in Women and Gender Studies, University of Missouri, Columbia,

Missouri; Bettina M. Beech, Department of

Psychology, University of Memphis, Tennessee (current affiliation, Department of Internal Medicine and Public Health, Vanderbilt University, Nashville,

Tennessee); Chanita Hughes-Halbert, Department of Psychiatry and Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania; Njeri Karanja, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland,

Oregon; Kristie J. Lancaster, Department of

Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, New York University, New York, New

York; Carmen D. Samuel-Hodge, Nutrition Department, Schools of Public Health and Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

North Carolina.

Back to top

References

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA 2006;295(13):1549-55.

- Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research. Bethesda (MD): National

Institutes of Health. http://www.obesityresearch.nih.gov/About/ Obesity_EntireDocument.pdf.

Accessed March 17, 2007.

- Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Ogden CL, Dietz WH.

Racial and ethnic differences in secular trends for childhood BMI, weight, and height.

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(2):301-8.

- Bish CL, Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Marcus M, Kohl HW 3rd, Khan LK.

Diet and physical activity behaviors among Americans trying to lose weight: 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obes Res 2005;13(3):596-607.

- McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, Lux L, Sutton S, Bunton AJ, et al. Screening and interventions for obesity in adults:

summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2003;139(11):933-49.

- Whitlock EP, Williams SB, Gold R, Smith PR, Shipman SA.

Screening and interventions for childhood overweight: a summary of evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics 2005;116(1):e125-44.

-

Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of

overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. National Institutes

of Health. [Published erratum in: Obes Res 1998;6(6):464]. Obes Res 1998;6

Suppl 2:51S-209S.

- Kumanyika SK. Obesity treatment in minorities. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of

obesity treatment. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Guilford Publications, Inc.; 2002. p. 416-46.

- Kumanyika SK. Cultural differences as influences in obesity treatment. In: Bray GA, Bouchard C, eds. Handbook of

obesity: clinical applications. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Marcel Dekker; 2004. Vol. 1, Chapter 3. p. 45-67.

- Bronner Y, Boyington JE.

Developing weight loss interventions for African-American women: elements of successful models. J Natl Med Assoc 2002;94(4):224-35.

- Yancey AK, Kumanyika SK, Ponce NA, McCarthy WJ, Fielding JE, Leslie JP, et

al. Population-based interventions engaging communities of color in healthy eating and active living: a review. Prev Chronic Dis 2004;1(1). http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/jan/03_0012.htm

- Booth SL, Sallis JF, Ritenbaugh C, Hill JO, Birch LL, Frank LD, et al.

Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutr Rev 2001;59(3 Pt 2):S21-39;

S57-65.

- Kumanyika SK.

Minisymposium on obesity: overview and some strategic considerations. Annu Rev Public Health 2001;22:293-308.

- French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW.

Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health 2001;22:309-35.

- Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F.

Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med 1999;29(6 Pt 1):563-70.

- Smelser JN, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, eds. America becoming. Racial trends and their consequences. Vol

II. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001.

- Kumanyika SK, Gary TL, Lancaster KJ, Samuel-Hodge CD, Banks-Wallace J,

Beech BM, et al.

Achieving healthy weight in African American communities: research priorities and perspectives. Obes Res 2005;13(12):2037-47.

- McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA. African American family life. Ecological and

cultural diversity. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2005.

- Think tank on enhancing obesity research at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Executive

summary. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2004. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/obesity/ob_res_exsum/ ob_res_exsum.pdf.

Accessed March 18, 2007.

- Roy Elveton, Carleton College. "Lebenswelt [Lifeworld]." The Literary Encyclopedia. http://www.litencyc.com/php/stopics.php?rec=true&UID=1539.*

Accessed March 18, 2007.

- Health, United States, 2006. With chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville

(MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2006.

- Hooks B. Sisters of the yam: black women and self-recovery. Boston (MA): South End Press; 1993.

- Hahn RA. Anthropology and the enhancement of public health practice. In: Hahn RA, Harris KW, eds. Anthropology and

public health. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 1999. Chapter 1. p. 3-24.

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, et al. Community-based

participatory research: assessing the evidence. Summary, evidence report/technology

assessment: no. 99. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality; 2004.

http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/cbprsum.htm

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB.

Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:173-202.

- Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies. Research and indigenous peoples. London

(UK): Zed Books, Ltd; 1999.

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Health and culture. Beyond the western paradigm. Thousand Oaks

(CA): Sage Publications; 1995.

- Kumanyika S, Grier S. Targeting interventions for low income and ethnic minority children. Future Child 2006;16(1):187-207.

- Taylor WC, Poston WSC, Jones L, Kraft MK. Environmental justice. Obesity, physical activity, and healthy eating.

J Phys Act Health 2006;3(Suppl 1):S30-S54.

- Kumanyika S. Obesity, health disparities, and prevention paradigms: hard questions and hard choices. Prev Chronic Dis

2005;2(4).

http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/oct/05_0025.htm

- African American Collaborative

Obesity Research Network. Participatory research on African American

community weight issues: defining the state of the art. Summary. Second

AACORN invited workshop. 2006 Aug 14-15; Philadelphia, PA.

http://www.aacorn.org/Acti2006-1075.html*

Back to top

|

|