|

|

Volume

6: No. 3, July 2009

SPECIAL TOPIC

Adolescent Obesity and Social Networks

Laura M. Koehly, PhD; Aunchalee Loscalzo, PhD

Suggested citation for this article: Koehly LM,

Loscalzo A. Adolescent obesity and social networks. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6(3):A99. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2009/

jul/08_0265.htm. Accessed [date].

PEER REVIEWED

Abstract

The prevalence of overweight among children worldwide is growing at an alarming rate.

Social relationships may contribute to the development of obesity through the interaction of biological, behavioral, and environmental factors. Although there is evidence that early environment influences the expression of obesity, very little research elucidates the social context of obesity among children or adolescents. Social network approaches can contribute to research on the

role of social environments in overweight and obesity and strengthen interventions to prevent disease and promote health. By capitalizing on the structure of the network system, a targeted intervention that uses social relationships in families, schools, neighborhoods, and communities

may be successful in encouraging healthful behaviors among children and their families.

Back to top

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight among children has tripled in the last 40 years. Although recent data suggest that childhood overweight rates have begun to plateau, 32% of youth aged 2 to 19 years are overweight or at risk of becoming overweight (1,2). Furthermore, childhood overweight contributes to type 2 diabetes, adult obesity, and heart disease, along with impaired self-esteem and depression (3).

Adolescent overweight is largely a product of familial obesity risk (4), but environmental influences can augment the expression of overweight in children with a family history of obesity, continuing into adulthood. A social network approach to research and intervention design accounts for social contexts such as family, schools, neighborhoods, or communities, revealing how people are interconnected and influence

one another. A social network approach is a relational

perspective that frames research involving individuals and their families and communities, in addition to the methodologic tools that

are used in social network analysis. We discuss the use of a social network approach in interventions for adolescent overweight by considering 1) recent developments in the science of obesity genetics, 2) the importance of social context, 3) communal coping as a mechanism for behavior change within social networks, and 4) specific recommendations for using

social networks to prevent overweight.

Back to top

Obesity and Family History

A recent study estimates that more than 70% of adiposity in 10-year-olds is

due to genetic factors, and approximately 20% is due to socioenvironmental

contributions (4). Genome-wide association studies have located common genetic

variants associated with fat mass, weight, and susceptibility to obesity.

Several genes isolated through these studies, including FTO (5) and MC4R (6),

may eventually help scientists to explain the global scale of the obesity

epidemic and the biological mechanism for the heritability of obesity in

families.

Other research has identified factors associated with the behavioral

transmission of obesity risk from parents to their children (7). Eating disinhibition, susceptibility to hunger, and eating in the absence of hunger all

appear to be biologically heritable traits. Thus, a child’s family health

history, along with shared behaviors and familial environments, must be

considered in efforts to prevent and treat obesity (8).

Back to top

Early Social Environments and Overweight

Excessive caloric intake and a lack of physical activity are 2 major

environmental causes of adolescent overweight. Both structural and behavioral

environments in which adolescent social networks operate are inextricably linked

to their eating behaviors and physical activity levels.

Early childhood feeding practices are usually established in the home and

often translate into eating patterns during adolescence. Variations in food

preferences and portions among preschool children are associated with the extent

to which parents introduce new foods and encourage healthful eating habits (9).

Moreover, maternal feeding practices appear to influence the dietary patterns of

girls, suggesting that the relational significance of parental influence on

their children may be sex-specific (10).

Likewise, early childhood activity levels translate into similar patterns of

physical activity during adulthood (11). Physical activity among adolescents is

a social behavior, which is partly dependent on neighborhoods and recreational spaces.

Built environments can limit or facilitate levels of adolescent physical

activity. Playgrounds that are accessible via sidewalks and safe intersections

have been associated with higher levels of physical activity among youth (12).

Back to top

Adolescent Overweight and Social Networks

Mutual friendship ties, not merely biological family or relationships found

within the household, can contribute to an adult’s risk of obesity (13), but

little is known about whether the social mechanisms associated with weight gain

in adults pertain to adolescents. Studies of adolescent social networks have

identified the extent to which clique formation, the tendency for

people to form social ties with others who are similar (14), are associated with

weight status and physical activity. One study found that adolescent friendships

tended to cluster on the basis of weight status (15). The boys who were friends

engaged in similar levels of physical activity; however, this finding was not

noted within girl friendship networks (16). Another study found similarities in

the consumption of sweet foods and fast foods and types of physical activities

among male friends, and female friends were similar in the time spent on

computer-based leisure activities (17).

The mechanisms of social influence on adolescent overweight vary, but all

depend on social interaction. Parents can serve as role models, especially for

younger children whose health behaviors are completely influenced by their

parents’ habits (18), and older children may look to their friends, teachers,

and community leaders as role models for their own health behaviors (19).

Indirect processes can occur through cultural or group norms and attitudes. For

example, adolescents’ attitudes about body image can be influenced by social and

cultural norms (20).

Back to top

Communal Coping

A social network approach fits within a socioecological model for obesity

interventions, because social networks form and operate within the social contexts that influence health behaviors and

behavior change (21). Capitalizing on these interpersonal relationships may

enhance the effectiveness of health promotion interventions (22).

Communal coping is a process in which interpersonal relationships are the

conduit to behavior change among multiple members within a particular social

network, such as families (23). Its use in obesity prevention is novel, because

it prioritizes relational over individual processes. From a communal coping

perspective, individuals define themselves in terms of their interconnectedness

and relationships with their family, friends, neighbors, and community. Thus,

when faced with a shared health problem, a cooperative approach to address the

problem that involves family and friends may be particularly effective (23).

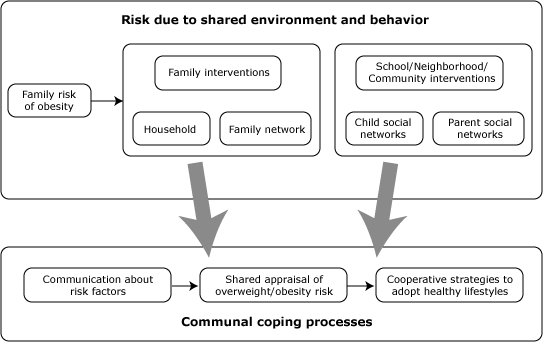

Health interventions that use communal coping can target 3 interpersonal

pathways (Figure 1): 1) communication about a health problem, such as shared

risk factors, 2) shared appraisals of the problem, and 3) development of

cooperative strategies to reduce negative impact (23). Interventions can focus

on educating family members about collective risk due to shared family history,

environment, and behaviors, and promoting increased communication about family

risk of overweight and associated diseases. Similar efforts can motivate

communication about shared risk factors among friends in neighborhoods and

communities, leading to shared appraisals among those who are socially

connected. The success of communal coping depends on cooperative support

mechanisms. Support can be directed at emotion-focused coping to address, for

example, low self-esteem or psychological impacts of stigma associated with

overweight and obesity. Cooperative support also can be geared toward problem-focused coping by

addressing dietary behavior and physical activity.

Figure 1. The communal coping framework. This

illustration shows the pathways through which increased risk due to shared

genes, environment, and behavior may lead to the process of communal coping.

Back to top

Using Social Network Approaches to Strengthen Obesity

Prevention

Obesity prevention must account for the complexity of overweight, including

a child’s familial risk of obesity and social relationships. Most previous interventions have focused on a single social sphere,

such as household or school. Furthermore, family-oriented interventions often engage

an affected child and a single caregiver, rather than considering the complex

social environment that might surround children and their families. An

intervention that focuses on the family system will have limited success without

consideration of the social influences on both parents’ and children’s behaviors

outside of the family context. Similarly, a school-based intervention that does

not consider the familial social environment or interpersonal influences within

the neighborhood or community settings would also be limited.

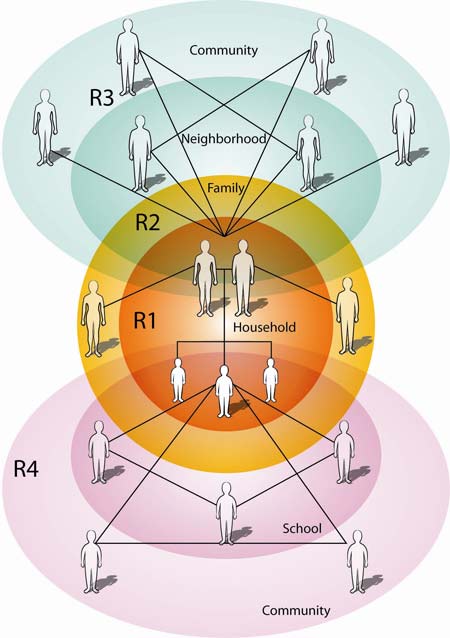

Thus, we recommend that interventions focus on 3 settings simultaneously

(Figure 2,

Table): R1 and R2) the household and the child’s

family outside of the household; R3) the neighborhood and community, to engage

the parents’ social network and social influences on the child outside of the

school setting; and R4) the school, to engage the child’s social network.

Figure 2. Recommendations (“R1” through “R4”) to

prevent and control adolescent overweight. This illustration shows how social

networks of children and parents interconnect with other social contexts that

are important to obesity prevention in adolescents.

Recommendation 1: Intervene with the family system, rather than with the

individual.

Primary prevention efforts may be more effective if they focus on the home

environment. To date, household-based interventions have been largely focused on

treatment of childhood overweight but not primary prevention. A detailed family

history capturing the constellation of family members who are overweight, and

associated diseases, can identify at-risk families for primary prevention

efforts. Adolescents can be engaged in the process of gathering family health

history of chronic illness and associated risk factors such as overweight, which

will provide an opportunity for families to communicate about their shared risks

(24).

Interventions based on the communal coping model could initially focus on

facilitating communication among household members and educating them about

their shared risk of disease. This process should engage multiple family members

and not be limited to an at-risk child and the primary caregiver. The key to

activating communal coping is to develop common appraisals of a shared health

threat among group members. In the case of a family-based intervention, a risk

assessment based on family history might motivate the perception of risk of

overweight as a household-level problem, warranting a household-level solution.

One model for developing risk assessments based on family risk is Family

Healthware. This software, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, produces an evaluation of an individual’s risk of

disease based on their family health history and recommends

health behaviors that may reduce their risk.

Recommendation 2: Tailor family-based interventions to the structure of the

family.

Because families are complex social systems, family-based interventions must

be flexible enough to adapt to the unique needs of individual families. Social

network approaches can be used to gather information on the existing

configuration of relationships within families, including family members outside

of the household, the composition of the family, the functional significance of

family ties, and the way social influence functions in each family. This

information can be used to determine the key people within the family who might

be able to exert a strong enough influence to change behavior. These optimally

positioned family members may receive training and education and be engaged as

“family leaders” who encourage cooperative strategies to increase physical

activity, prepare healthy meals, and provide moral support that may help to

sustain long-term behavior change within the family.

Cultural and sociodemographic factors are associated with the way families

are organized, the social significance of food, food preferences and eating

behaviors, and the way children are socialized. A formative assessment can

elucidate shared beliefs and behaviors of families that may not be apparent

through structural analysis. Such knowledge can lead to the design of culturally

appropriate intervention materials, which can then be implemented according to

unique family characteristics.

Recommendation 3: Design support mechanisms for parents and adult family

members on the basis of their social ties within the community.

Preventing childhood overweight is likely to have the most sustainability

when it is implemented early in the immediate family environments of young

children and continues through interventions in schools, neighborhoods, and

other community settings. Young children often model the health behaviors of

parents and other adults in their lives (18,19). To be positive role models for

the children in their homes, adult family members may need to change their own

lifestyles.

At the same time, the health of adult family members depends somewhat on

their social ties (13). Social ties and the structure of these ties can affect

behavior and health through social influence, social support, access to

resources, and access to information. Social psychological theories suggest that

a person’s friends are likely to share similar lifestyle behaviors, such as diet

and levels of physical activity, and thus be at similar risk for overweight.

One way to support obesity interventions among influential adults in

adolescents’ lives is to consider the social ties that influence adult eating

and physical activity behaviors. For example, using a social network approach,

cohesive subgroups of friends within neighborhoods and communities could be

identified for health promotion. A central person within the group can be

identified on the basis of the network’s structure and trained to act as the

liaison between the friendship network and the intervention team. The peer

leader can create opportunities for discussing lifestyle risk factors, provide

educational materials developed by the intervention team, and organize group

activities aimed at promoting healthful lifestyles among friends. By using the

naturally occurring structure of a group of friends, the designated leader will

have credibility within the group and be more effective in relaying helpful

information on diet and physical activity.

Neighborhood or community health promotion activities can be designed and

targeted to these friendship networks. For example, neighborhood “house parties”

may provide opportunities for friends to meet monthly, preassemble healthy

meals, and discuss educational materials with tips on how to provide a healthy

diet to their family. A similar approach can be used to increase physical

activity, for example, a coordinated effort within the friendship network to

exercise together several times a week. Targeting intervention activities to the

natural groupings of friends capitalizes on the social influence processes

inherent within friendship networks as well as the continued provision of social

support and encouragement of healthful lifestyles.

Recommendation 4: Use peer networks to encourage increased physical

activity.

Because adolescents seem to cluster according to physical activity levels

(15,17), network-based interventions may be particularly effective in developing

coordinated physical activity efforts among adolescent friends. The most popular

of these interventions encourages change in friendship networks through a peer

leader, a central influential person, or opinion leader selected on the basis of

the structure of social ties among the children within a classroom or community

organization. This approach is easy to implement, has been effective in smoking

prevention interventions (25), and has the potential to increase physical

activity among adolescents.

Overweight adolescents are often socially isolated, which in turn may lead to

“emotional eating” (3). Social network interventions might focus specifically on

helping isolated overweight adolescents form new social ties that have health

benefits. Classrooms and community settings are ideal for such activities. A

buddy system between people who were previously unconnected has been successful

in reducing social isolation; this peer-teaching intervention involved

older-younger schoolchildren pairs (26).

Team-based physical activity has been effective for weight reduction and

lifestyle change when at-risk and overweight youth were members of organized

sports teams (27). Motivating overweight youth to participate in these

team-based activities may require special support, such as school-based policies

and community programs designed specifically to meet the needs of children who

are overweight. One social network approach to encouraging participation in

organized sports could involve assigning team membership based on naturally

occurring friendships and cliques among overweight youth. This strategy would

simultaneously increase physical activity levels, encourage positive peer

influences on weight reduction, and reduce social isolation (3).

Back to top

Conclusion

According to Barabasi, “Growing interest in interconnectedness has brought into focus an often ignored issue: networks pervade all aspects of human health” (28).

Network perspectives will continue to advance the study of childhood and adolescent overweight. We suggest a new and stronger focus on the potential to garner interpersonal processes to address the obesity problem. Consideration of family and social networks may contribute to sustainable behavior change and improve the effectiveness of prevention and treatment interventions. Although challenging, curbing the obesity epidemic will undoubtedly depend on the coordinated efforts of many agencies

and institutions to support culturally sensitive programs that consider both family and peer interactions.

Back to top

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported in part by funding from the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. We thank Thomas Valente, Donna Stroup, Valerie Johnson, and

4 anonymous reviewers for reviewing an earlier version of the manuscript.

Back to top

Author Information

Corresponding Author: Laura M. Koehly, PhD, National Institutes of Health, Building 31, B1B37D, 31 Center Dr, MSC 2073, Bethesda, MD 20892. Telephone: 301-451-3999. E-mail:

koehlyl@mail.nih.gov.

Author Affiliation: Aunchalee Loscalzo Palmquist, National

Human Genome Research Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

Back to top

References

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2000.

- Ogden C, Carroll M, Flegal K.

High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003-2006. JAMA 2008;299(20):2401-5.

- Fisberg M, Baur L, Chen W, Hoppin A, Koletzko B, Lau D.

Obesity in children and adolescents: working group report of the

Second World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004;39:S678-87.

- Wardle J, Carnell S, Haworth CMA, Plomin R.

Evidence for a strong genetic influence on childhood adiposity despite the force of the obesogenic environment. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87(2):398-404.

- Haworth CM, Carnell S, Meaburn EL, David OS, Plomin R, Wardle J.

Increasing heritability of BMI and stronger associations with the

FTO gene over childhood. Obesity 2008;16(12):2663-8.

- Loos R, Lindgren C, Li S, Wheeler E, Zhao J, Prokopenko I, et al.

Common variants near

MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk for obesity. Nat Genet 2008;40(6):768-75.

- Breen FM, Plomin R, Wardle J.

Heritability of food preferences in young children. Physiol Behav 2006;88:443-7.

- Kral TVE, Faith MS.

Influences on child eating and weight development from a behavioral genetics perspective. J Pediatr Psychol 2008 April. [Epub ahead of print].

- Russell CG, Worsley A.

A population-based study of preschoolers' food neophobia and its association with food preferences. J Nutr Educ Behav 2008;40:11-9.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK.

Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:215-20.

- Lau PW, Lee A, Ransdell L.

Parenting style and cultural influences on overweight children's attraction to physical activity. Obesity 2007;15(9):2293-302.

- Davison KK, Lawson CT.

Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2006;3:19.

- Christakis N, Fowler J.

The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med 2007;357(4):370-9.

- Koehly LM, Shivy VA. Social environments and social contexts: social network applications in person environment psychology. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000.

- Valente T, Fujimoto K, Chou C, Spruijt-Metz D. Adolescent affiliations and adiposity: a social network analysis of adolescent friendships and weight status. J Adolesc Health. In press.

- Fujimoto K, Valente T, Chou C, Spruijt-Metz D. Social network influences on adolescent weight and physical activity. Paper presented at: Sunbelt XXVIII International Sunbelt Social Network Conference; 2008; St. Pete Beach, FL.

- de la Haye K, Robins G, Mohr P, Wilson C. Obesity-related behaviors in adolescent friendship networks. Social Networks. In press.

- Scanglioni S, Salvioni M, Galimberti C.

Influence of parental attitudes in the development of children eating behaviour. Br J Nutr 2008;99(Suppl 1):S22-5.

- Cutting T, Fisher J, Grimm-Thomas K, Birch L.

Like mother, like daughter: familial patterns of overweight are mediated by mothers’ dietary disinhibition. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:608-13.

- Boyington JE, Carter-Edwards L, Piehl M, Hutson J, Langdon D, McManus S. Cultural attitudes toward weight, diet, and physical activity among overweight African American girls. Prev Chronic Dis 2008;5(2):1-9.

http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/apr/07_0056.htm.

- Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 462-84.

- Koehly LM, McBride C. Genomic risk information for common health conditions: Maximizing kinship-based health promotion. In: Tercyak K, editor. Handbook of genomics and the family. New York (NY): Springer; In press.

- Afifi T, Hutchinson S, Krouse S. Toward a theoretical model of communal coping in postdivorce families and other naturally occurring groups. Commun Theory 2006;16:378-409.

- Williams R, Hunt S, Heiss G, Povince M, Bensen J, Higgins M.

Usefulness of cardiovascular family history data for population-based preventive medicine and medical research (The Health Family Tree Study and the NHLBI Family Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2001;87:129-35.

- Valente T, Hoffman B, Ritt-Olson A, Lichtman K, Johnson A.

Effects of a social-network method for group assignment strategies on peer-led tobacco prevention programs in schools. Am J Public Health 2003;93(11):1837-43.

- Stock S, Miranda C, Evans S, Plessis S, Ridley J, Yeh S, et al.

Health buddies: a novel, peer-led health promotion program for the prevention of obesity and eating disorders in children in elementary school. Pediatrics 2007;120(4):e1059-68.

- Weintraub D, Tirumalai E, Haydel K, Fujimoto M, Fulton J, Robinson T.

Team sports for overweight children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162(3):232-7.

- Barabasi A.

Network medicine — from obesity to the “diseasome.” N Engl J Med 2007;357(4):404-7.

Back to top

|

|