|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Comparison of Office Visit and Nurse Advice Hotline Data for Syndromic Surveillance --- Baltimore-Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Area, 2002Jade Vu Henry,1 S. Magruder,2

M. Snyder1

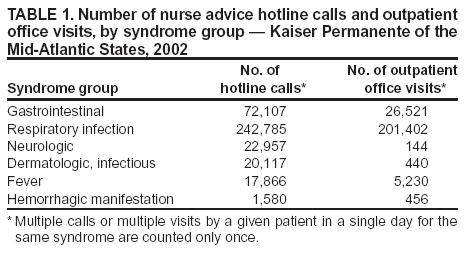

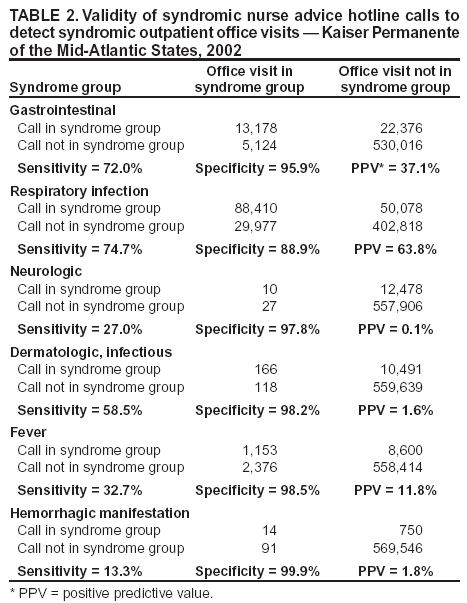

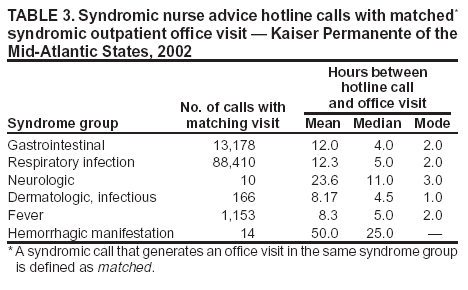

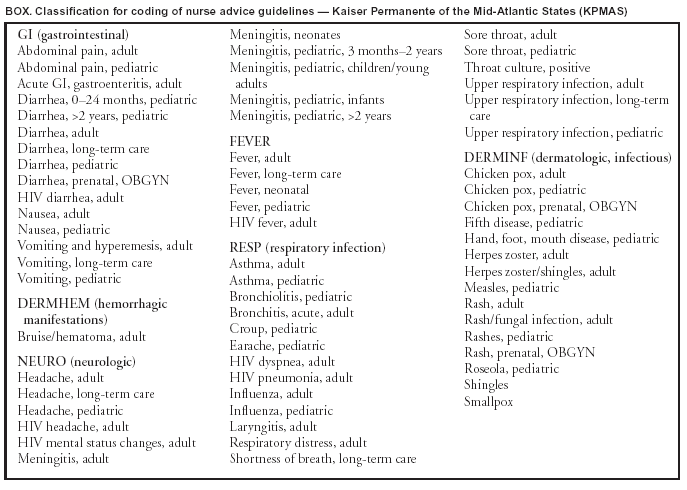

Corresponding author: Jade Vu Henry, 2102 East Jefferson Street, Rockville, MD 20849. Telephone: 301-816-6891; Fax: 301-816-7465; E-mail: jade.v.henry@kp.org. AbstractIntroduction: Kaiser Permanente of the Mid-Atlantic States (KPMAS) is collaborating with the Electronic Surveillance System for Early Notification of Community-Based Epidemics II (ESSENCE II) program to understand how managed-care data can be effectively used for syndromic surveillance. Objectives: This study examined whether KPMAS nurse advice hotline data would be able to predict the syndrome diagnoses made during subsequent KPMAS office visits. Methods: All nurse advice hotline calls during 2002 that were linked to an outpatient office visit were identified. By using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes, outpatient visits were categorized into seven ESSENCE II syndrome groups (coma, gastrointestinal, respiratory, neurologic, hemorrhagic, infectious dermatologic, and fever). Nurse advice hotline calls were categorized into ESSENCE II syndrome groups on the basis of the advice guidelines assigned. For each syndrome group, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of hotline calls were calculated by using office visits as a diagnostic standard. For matching syndrome call-visit pairs, the lag (i.e., the number of hours that elapsed between the date and time the patient spoke to an advice nurse and the date and time the patient made an office visit) was calculated. Results: Of all syndrome groups, the sensitivity of hotline calls for respiratory syndrome was highest (74.7%), followed by hotline calls for gastrointestinal syndrome (72.0%). The specificity of all nurse advice syndrome groups ranged from 88.9% to 99.9%. The mean lag between hotline calls and office visits ranged from 8.3 to 50 hours, depending on the syndrome group. Conclusions: The timeliness of hotline data capture compared with office visit data capture, as well as the sensitivity and specificity of hotline calls for detecting respiratory and gastrointestinal syndromes, indicate that KPMAS nurse advice hotline data can be used to predict KPMAS syndromic outpatient office visits. IntroductionAcross the United States, managed care organizations operate clinical and administrative information systems to support the routine delivery of health-care services to their members. Data from these information systems offer promise for enhancing public health surveillance activities in communities where managed care organizations operate (1--4). However, despite the widely recognized potential of using managed-care data for tracking community health indicators, managed care organizations and public health departments have previously had limited incentive to form alliances to improve public health surveillance (5). In 2001, when residents of the Baltimore-Washington, D.C., metropolitan area were diagnosed with inhalational anthrax, Kaiser Permanente of the Mid-Atlantic States (KPMAS) experienced a public health emergency requiring daily interaction with local health authorities. In the course of delivering health care to victims of this biologic terrorism, KPMAS employees became acutely aware of the need for stronger links with public health agencies at all government levels (6). While responding to the anthrax crisis, KPMAS was also able to demonstrate the public health potential of its administrative and clinical information systems, having searched its databases to identify and contact hundreds of enrollees at-risk to recommend testing and treatment options (7). Drawing from the lessons of this front-line experience, KPMAS began looking for substantive ways to support the local public health infrastructure. Since 2002, the KPMAS Research Department has collaborated with the Electronic Surveillance System for Early Notification of Community-Based Epidemics II (ESSENCE II) program. KPMAS researchers view ESSENCE II as a community health partnership --- a voluntary collaboration of diverse community organizations that are pursuing a shared interest in community health (8). The ESSENCE II program seeks to strengthen the local public health infrastructure by developing a regional syndromic surveillance system. To achieve this objective, ESSENCE II has drawn together a multisector, multidisciplinary group of researchers, health-care providers, and public health authorities with expertise in medicine, mathematics, and public health, as well as access to health data. KPMAS operates a secure information system that routinely captures data from an array of health-care operations, including laboratory tests, radiology procedures, pharmacy prescriptions, inpatient and outpatient visits, as well as membership demographics, appointment history, clinician notes, and nurse advice hotline calls. All of these data sources have potential value for syndromic surveillance. However, limited staff and funding are available to make KPMAS health-care information accessible for public health surveillance. Understanding the relative strengths and weaknesses of each KPMAS data stream can help prioritize information-technology investments for syndromic surveillance. To assess the performance of potential new data streams for the ESSENCE II surveillance system, this paper compares the epidemiologic properties of KPMAS nurse advice hotline data with outpatient office visit data obtained during January 1--December 31, 2002. The goal of this study was to determine whether nurse advice hotline data would be able to predict the syndromic diagnoses made during a subsequent office visit. MethodsPopulation and Delivery SystemKPMAS contracts with 36 local hospitals and operates 30 outpatient medical centers to deliver health services to a population of >500,000 members. To facilitate the continuity of care, each member is assigned a unique permanent identification number that can be used to retrieve and link all administrative and clinical data. Appointment scheduling and the nurse advice hotline function together within the KPMAS call center, which serves as a major entry point into the delivery system. Appointment clerks in the call center schedule routine appointments, while nurses operate an advice hotline to administer protocol-driven, medically appropriate advice over the telephone and to schedule acute-care office visits when necessary. In 2002, 369,646 members made 1,497,686 calls to the nurse advice hotline. Data Link Between Individual Nurse Advice Hotline Calls and Outpatient Office VisitsThe KPMAS information system captures not only the date and time a patient is seen for an outpatient office visit (Encounter_Date), but also the date and time that appointment is scheduled (Enc_File_Date). A third data field (Advice_Date) captures the date and time the patient contacted the nurse advice hotline. For this study, a hotline call and an office visit were defined as linked if all of the following criteria were met: 1) the patient identification number assigned to the hotline call matched the patient identification number assigned to the office visit; 2) the date of the hotline call matched the date the patient called for the appointment; and 3) the time of the hotline call either matched or preceded the time the patient called for an appointment. Categorizing KPMAS Data into Syndromic GroupsAll outpatient visits are assigned one or more diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). These diagnostic codes reflect the patients' presenting conditions, symptoms, presumed diagnoses, and definitive diagnoses. Before this study, ESSENCE II developed sets of ICD-9 codes representing clinical manifestations of potential infectious disease outbreaks (9). Those sets of ICD-9 codes were used to categorize all KPMAS outpatient visits during 2002 into seven syndrome groups: coma, gastrointestinal, respiratory, neurologic, hemorrhagic, infectious dermatologic, and fever. The information system that supports the KPMAS nurse advice hotline does not use the ICD-9 coding system. Instead, as nurses speak with patients, they select one or more KPMAS advice guidelines from a drop-down menu on the computer screen. These advice guidelines are based on 586 current KPMAS nurse advice clinical-practice protocols that correspond to patient-reported symptoms and presumed diagnoses. The KPMAS advice guidelines were classified into syndrome groups corresponding to the seven ICD-9--based ESSENCE syndrome categories (Box). Of the 586 KPMAS advice guidelines, 68 were used to define syndrome categories for nurse advice hotline calls (the remaining 518 were for conditions not of interest for syndromic surveillance). Because none of the advice guidelines corresponded to the ESSENCE II coma syndrome group, this category was dropped from analysis and only six of the seven categories were used. All nurse advice hotline calls received during 2002 were categorized according to the new syndrome groups. Approximately 20% of all hotline calls were assigned at least one syndromic advice guideline. The remaining 80% of hotline calls were associated with advice guidelines not relevant to syndromic surveillance and therefore not used in the hotline syndrome classification scheme. Because more than one ICD-9 diagnosis can be assigned to a patient during a given office visit, single office visits can fall into more than one ESSENCE syndrome group and be counted multiple times. Similarly, a nurse can use more than one advice guideline during a given call, in which case the call would fall into more than one advice syndrome group and be counted more than once. Multiple calls or multiple visits by a given patient in a single day for the same syndrome are counted only once. AnalysisThe total numbers of hotline calls and outpatient visits by syndrome group received during January 1--December 31, 2002, were determined and compared. All hotline calls linked to a subsequent outpatient visit were then identified. For each syndrome group, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of hotline calls was calculated, using office visits as a diagnostic standard. All hotline calls whose syndrome assignments matched those of the linked office visit were identified. For each of these matching syndrome call-visit pairs, the time lag (i.e., the number of hours that elapsed between the date and time the patient spoke to an advice nurse [Advice_Date] and the date and time the patient was seen for the office visit [Encounter_Date]) was calculated. Univariate statistics on this time lag were then generated. The study was reviewed and approved by the legal department of the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute, as well the KPMAS Institutional Review Board for the protection of human subjects. All analysis of patient-level data was performed by researchers at KPMAS. No patient-level data were released from KPMAS for this analysis. ResultsTotal nurse advice hotline calls and total outpatient office visits, by syndrome group, were compared (Table 1). Of all syndrome groups, respiratory and gastrointestinal syndromes generated the highest volume of hotline calls and office visits. Within every syndrome group, patients made at least twice as many hotline calls as office visits, with the exception of the respiratory syndrome category, which resulted in 242,785 hotline calls and 201,402 office visits. Approximately 570,500 hotline calls were linked to an office visit. The exact count varies slightly among syndrome groups because multiple calls or multiple visits by a given patient in a single day for the same syndrome were counted only once. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of hotline calls for detecting syndromes diagnosed during office visits were calculated (Table 2). Of all syndrome groups, the sensitivity of hotline calls for respiratory syndrome was highest (74.7%), followed by hotline calls for gastrointestinal syndrome (72.0%). Hotline calls for respiratory and gastrointestinal syndromes also had the highest positive predictive value. Sensitivity was lowest for hotline calls in the hemorrhagic group. The specificity of all nurse advice syndrome groups was high, ranging from 88.9% to 99.9%. Univariate statistics for the lag between syndromic hotline calls and their matching syndromic office visits were generated (Table 3). The mean lag between hotline calls and office visits ranged from 8.3 to 50 hours, depending on the syndrome group. Hotline calls in the hemorrhagic syndrome category provided the greatest mean lead time (50 hours) over corresponding office visits; however, hotline calls and office visits were both categorized as hemorrhagic in only 14 instances. The median lead time ranged from 4 hours for gastrointestinal and dermatologic/infectious syndromes to 25 hours for hemorrhagic syndrome. The mode for the lag ranged from 1 to 3 hours, depending on the syndrome. DiscussionAnalysis indicates that nurse advice hotline data is 4--50 hours timelier for syndrome detection than outpatient office visit data, depending on the syndrome group. This lead time might even be substantially greater because ICD-9 codes for KPMAS office visits are not immediately entered into the information system; as much as a 1-month lag can exist between the time a patient is seen and the time information from that visit is available for data analysis. Of>1 million hotline calls made during 2002, approximately 570,500 were linked to an outpatient visit. KPMAS patients made at least twice as many hotline calls as office visits within each syndrome category, with the exception of respiratory syndrome. A critical consideration in assessing the ability of syndromic advice calls to detect syndromic office visits is that many advice calls do not generate an office visit. Although all of the hotline call syndrome groups demonstrated high specificity relative to office visits, sensitivity and positive predictive value varied according to syndromic group. Further research is needed to explain the differences observed between hotline data and office-visit data. The performance of hotline data might be compromised by the data stream's emphasis on symptoms rather than clinical presentations and definitive diagnoses. Alternatively, these observed discrepancies might identify opportunities to add or remove advice guidelines from syndrome classifications of nurse advice hotline calls. Patient health-seeking behavior might also account for part of the differences observed between the number of calls and similarly grouped visits (e.g., work requirements, child-care needs, or transportation barriers might lead certain patients to use the advice hotline exclusively in place of a clinical examination). Finally, coding practices and other provider behaviors, as well as delivery-system factors (e.g., appointment access), might generate differences between counts of calls and visits. Health-services research aimed at understanding how patient, provider, and delivery-system factors relate to syndrome classifications might be helpful in establishing the theoretical underpinnings for effective outbreak-detection algorithms. ConclusionsThis study examined the relative value of two alternative health-care data streams, nurse advice hotline calls and outpatient office visits, collected from a single, integrated delivery system. The timeliness of hotline data capture compared with office visit data capture, as well as the sensitivity and specificity of hotline calls for detecting respiratory and gastrointestinal syndromes, indicate that KPMAS nurse advice hotline data can be used to predict KPMAS syndromic outpatient office visits. This analysis did not attempt to address whether KPMAS data could be used to detect epidemics in the broader Washington, D.C.-area community. Additional studies assessing the external generalizability of KPMAS data should be performed to determine whether KPMAS can serve in a sentinel surveillance capacity. Acknowledgments Staff from the U.S. Department of Defense, Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System, provided guidance in creating the syndrome categories for KPMAS advice guidelines, and Eileen McLaughlin shared her expertise on the KPMAS Call Center operations and information systems. This work was sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) as part of the Bio-ALIRT program. This paper also benefited from the comments of an anonymous reviewer. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Table 3  Return to top. Box  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/14/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/14/2004

|