|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. First Reports Evaluating the Effectiveness of Strategies for Preventing Violence: Early Childhood Home VisitationFindings from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services Prepared by The material in this report was prepared by the Epidemiology Program Office, Stephen B. Thacker, M.D., Director; Division of Prevention Research and Analytic Methods, Richard E. Dixon, M.D., Director. SummaryEarly childhood home visitation programs are those in which parents and children are visited in their home during the child's first 2 years of life by trained personnel who provide some combination of the following: information, support, or training regarding child health, development, and care. Home visitation has been used for a wide range of objectives, including improvement of the home environment, family development, and prevention of child behavior problems. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services (the Task Force) conducted a systematic review of scientific evidence concerning the effectiveness of early childhood home visitation for preventing several forms of violence: violence by the visited child against self or others; violence against the child (i.e., maltreatment [abuse or neglect]); other violence by the visited parent; and intimate partner violence. On the basis of strong evidence of effectiveness, the Task Force recommends early childhood home visitation for the prevention of child abuse and neglect. The Task Force found insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of early childhood home visitation in preventing violence by visited children, violence by visited parents (other than child abuse and neglect), or intimate partner violence in visited families. (Note that insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness should not be interpreted as evidence of ineffectiveness.) No studies of home visitation evaluated suicide as an outcome. This report provides additional information regarding the findings, briefly describes how the reviews were conducted, and provides information that can help in applying the recommended intervention locally. BackgroundJuvenile violence, child maltreatment, and intimate partner violence are substantial problems in the United States. In the last 25 years, juveniles aged <18 years have been involved as offenders in at least 25% of serious violent victimizations in the United States. Rates of homicide victimization among youth aged <15 years are five times higher in the United States than they are in 25 other industrialized nations for which data are available, and rates of firearm-related homicide are approximately 16 times higher in the United States than in those same nations (1,2). In 1994, 33% of juvenile homicides involved a juvenile offender. Since 1976 or earlier, the peak rate of homicide in the United States has occurred among persons aged 18--24 years. In 1999, suicide was the sixth leading cause of death among persons aged 5--14 years and the third leading cause of death among those aged 15--24 years. In 1999, 4.1% of children (aged <18 years) were reported to be victims of maltreatment. Of those reports, 33.8% were investigated by child protective services and not confirmed; however, additional cases of maltreatment were not reported, further complicating this picture (2--4). Child maltreatment can include physical, sexual, or emotional abuse; physical, emotional, or educational neglect; or a combination of abuse and neglect. Not only is child maltreatment a form of violence in itself, it also contributes to adverse consequences among maltreated children, including early pregnancy, drug abuse, school failure, mental illness, and suicidal behavior (5). Children who have been physically abused are more likely to perpetrate aggressive behavior and violence later in their lives, even when other risk factors for violence are taken into account (6,7). Because abuse and neglect are both associated with poverty and single-parent households, many home visitation programs in the United States are directed to poorer, minority, and single-parent families. Given that 12% of 4 million U.S. births in 1999 were to teenage mothers, 33% were to single mothers, and 22% of mothers had less than a high school education, the population at risk is substantial (8). Intimate partner violence victimizes men as well as women in the United States, but women are three times as likely to be victims as are men (9). During her lifetime, one of four women in the United States will be the victim of partner violence: 7.7% will be victims of rape and 22.1% will be victims of other physical assault. Violent victimization of women, including threats of rape and sexual assault, is greatest among women aged 16--19 years. Such violence can also have severe physical and mental health consequences for victims (10). Early childhood home visitation has been used for a wide range of public health goals for both visited children and

their parents, including not only violence reduction and other health outcomes but also health-related outcomes such as educational achievement, problem-solving skills, and greater access to

social services and other resources (11,12). Home visitation

programs are common in Europe, where they are most often made available to all childbearing families, regardless of estimated risk of child-related health or social problems

(13). This review assesses scientific evidence concerning the effectiveness of

early childhood home visitation in preventing violence by the visited child against others or self (i.e., suicidal behavior), violence against the child (i.e., maltreatment [abuse or neglect]), violence by the visited parent, and intimate partner violence.

The independent, nonfederal Task Force on Community Preventive Services (the Task Force) is developing the Guide to Community Preventive Services (the Community Guide) with the support of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) in collaboration with public and private partners. Although CDC provides staff support to the Task Force for development of the Community Guide, the recommendations presented in this report were developed by the Task Force and are not necessarily the recommendations of DHHS or CDC. This report is one in a series of topics included in the Community Guide, a resource that includes multiple systematic

reviews, each focusing on a preventive health topic. A short overview of the process used by the Task Force to select and review evidence and summarize its findings is included in this report. A full report on the findings and supporting evidence

(including discussions of applicability, additional benefits, potential harms, and existing barriers to implementation), costs and cost-benefit of the intervention, and remaining research questions will be published in the

American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

The Community Guide uses systematic reviews to evaluate the evidence of intervention effectiveness, and the Task Force bases its recommendations on the findings of these reviews. Recommendations regarding interventions reflect the strength of the evidence of effectiveness (i.e., sufficient or strong evidence of effectiveness) (14).* Other types of evidence can also affect a recommendation. For example, evidence of harms resulting from an intervention might lead to a recommendation that the intervention not be used if adverse effects outweigh improved outcomes. When interventions are determined to be effective, their costs and cost effectiveness are evaluated, insofar as relevant information is available (15). The instrument used to systematically abstract the economic data is available at http://www.thecommunityguide.org/methods/econ-abs-form.pdf. Although the option exists, the Task Force has not yet used economic information to modify recommendations. A finding of insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness should not be interpreted as evidence of ineffectiveness but rather as an indicator that additional research is needed before the effectiveness of the intervention can be determined. In contrast, sufficient or strong evidence of harmful effect(s) or of ineffectiveness leads to a recommendation that the intervention not be used. The Community Guide's methods for conducting systematic reviews and linking evidence to recommendations have been described elsewhere (14). In brief, for each Community Guide topic, a multidisciplinary team conducts a review by performing the following actions:

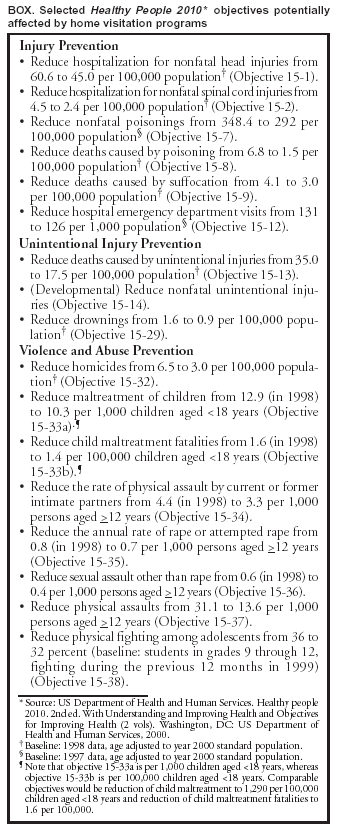

For the systematic review of violence prevention intervention programs, early childhood home visitation was identified as a high-priority intervention by a group of consultants† representing diverse experience. They generated a comprehensive list of strategies and created a priority list of interventions for review based on 1) the potential to reduce violence in the U.S. population; 2) the potential benefits of expanding use of seemingly effective, but underused interventions and reducing use of seemingly ineffective, but overutilized interventions; 3) current interest among violence prevention audiences; and 4) diversity among intervention types. Home visitation programs, reviewed in this article, might be useful in reaching several objectives of Healthy People 2010 (16), the disease prevention and health promotion agenda for the United States. These objectives identify major preventable threats to health and focus the efforts of public health systems, legislators, and law enforcement officials in addressing those threats. Many of the Healthy People objectives in Chapter 15, "Injury and Violence Prevention," relate to home visitation and its proposed effects on violence-related outcomes (Box). To be included in the review of effectiveness, studies had to 1) be primary investigations of the intervention selected for evaluation rather than, for example, guidelines or reviews; 2) provide information on at least one outcome of interest from the list of violent outcomes preselected by the team; 3) be conducted in Established Market Economies;§ and 4) compare outcomes in groups of persons exposed to the intervention with outcomes in groups of persons not exposed or less exposed to the intervention (whether the comparison was concurrent between groups or before-and-after within the same group). The search covered any research published before July 2001. The purpose of this review was to assess the effectiveness of home visitation programs in preventing violence. Home visitation programs have focused on diverse aspects of child and family development. In this review, home visitation was defined as a program that includes visitation of parents and children in their home by trained personnel who convey information, offer support, provide training, or perform a combination of these activities. Visits must occur during at least part of the child's first 2 years of life but may be initiated during pregnancy and may continue after the child's second birthday. Participation may be voluntary or mandated. Visitors may be nurses, social workers, other professionals, paraprofessionals, or community peers. Home visitation programs are commonly targeted to specific population groups: low-income; minority; young; less educated; first-time mothers; substance abusers; children at risk for abuse or neglect; and low birthweight, premature, disabled, or developmentally compromised infants. Visitation programs include (but are not limited to) one or more of the following components: training of parent(s) on prenatal and infant care, training on parenting, child abuse and neglect prevention, developmental interaction with infants or toddlers, family planning assistance, development of problem-solving skills and life skills, educational and work opportunities, and linkage with community services. In addition to home visits, programs can include day care; parent group meetings for support, instruction, or both; advocacy; transportation; and other services. When such services are provided in addition to home visitation, the program is considered multicomponent. The systematic review development team (the team) reviewed studies of home visitation only if they assessed violent outcomes. If violence was not the primary target or outcome of the visitation, the study was included if it met epidemiologic criteria and assessed violent outcomes. The effects of other outcomes were not systematically assessed but are reported insofar as they are addressed in the studies reviewed. The studies reviewed examined any of four violent outcomes:

The team developed an analytic framework for the early childhood home visitation intervention, indicating possible causal links between home visitation and predefined outcomes of interest. To make recommendations, the Task Force required that studies show decreases in preselected direct or proxy measures for at least one of the four categories of violent behavior described previously. If both direct and proxy measures were available, preference was given to the direct measure. Electronic searches for intervention studies were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, ERIC, National Technical Information Service (NTIS), PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS), and CINAHL.¶ Also reviewed were the references listed in all retrieved articles as well as additional reports as identified by the team, the consultants, and specialists in the field. Journal articles, government reports, books, and book chapters were included in the review. Each study that met the inclusion criteria was evaluated by using a standardized abstraction form (17) and was assessed for suitability of the study design and threats to validity (14). On the basis of the number of threats to validity, studies were characterized as having good, fair, or limited execution. Results on each outcome of interest were obtained from each study that had good or fair execution. Measures adjusted for the effects of potential confounders were used in preference to crude effect measures. A median was calculated as a summary effect measure for outcomes of interest. For bodies of evidence consisting of seven or more studies, an interquartile range was presented as an index of variability. Unless otherwise noted, the results of each study were represented as a point estimate for the relative change in the violent outcome rate associated with the intervention. Percentage changes were calculated by using the following formulas:

Effect size = [(Ipost / Ipre) / (Cpost / Cpre)] - 1

Effect size = (Ipost - Cpost) / Cpost

Effect size = (Ipost - Ipre) / Ipre The strength of the body of evidence of effectiveness was characterized as strong, sufficient, or insufficient on the basis of

the number of available studies, suitability of study designs for evaluating effectiveness, quality of execution of the

studies, consistency of the results, and effect size

(14).

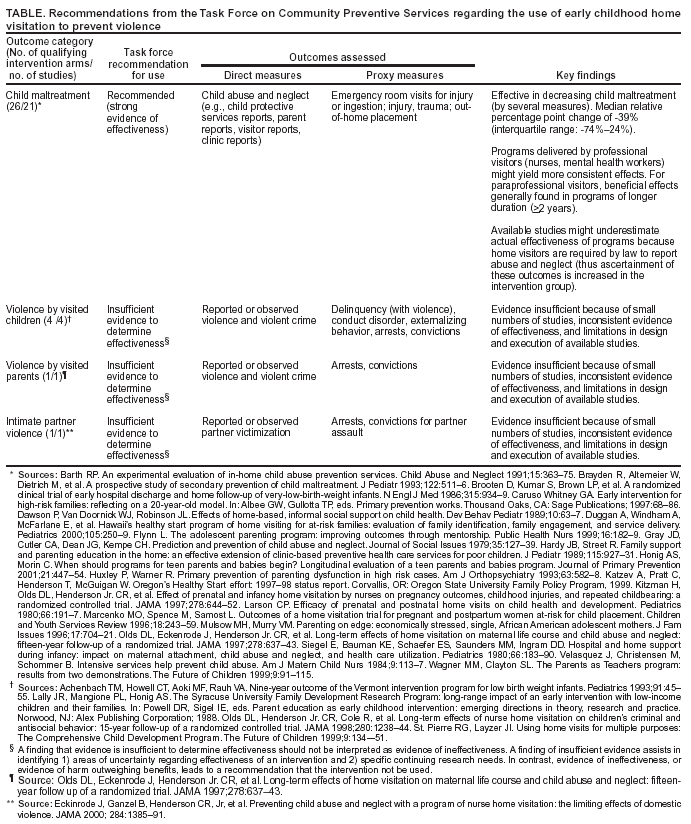

The systematic review development team identified four studies that evaluated effects of early childhood home visitation on violence by visited children. Because the results of these studies were inconsistent, the Task Force concluded that evidence was insufficient to determine the effectiveness of early childhood home visitation in preventing violence by visited children. Evidence from one study (as assessed by self-reported delinquency, the team's preferred measure) indicated no benefit and was inconsistent with evidence from the same study as assessed by other measures (e.g., arrests and convictions) (18). A second study (19) indicated benefit of home visitation, and the two remaining studies (20,21) suggested no difference. No study evaluated the effects of home visitation on suicide by visited children. The studies also yielded insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of early childhood home visitation in preventing violence by visited parents (other than child abuse) or intimate partner violence in visited families. The team identified only one study that evaluated effects of early childhood home visitation on violence by visited parents (other than child abuse) (22). This study indicated a beneficial effect, but one that was statistically significant only among low-income, single mothers. Similarly, only one study evaluated effects of home visitation on intimate partner violence in visited families (23). Evidence from this single study of partner violence indicated no statistically significant effect. The team also identified 22 studies (representing 27 intervention arms) that evaluated effects of early childhood home visitation on child maltreatment. Participation in all programs was voluntary. Outcomes assessed were reported and confirmed abuse and neglect, hospital records of injury or ingestion (which may be associated with abuse or neglect), and out-of-home placement (i.e., removal from the home). One study (representing one intervention arm) was excluded because of limitations in its execution; the remaining 21 studies (with 26 intervention arms) were included in the body of evidence. Additionally, three economic studies were included in the review. Both the costs and benefits of early childhood home visitation were assessed in one study, whereas the other two studies estimated program costs only. A summary of key findings and recommendations is presented (Table). On the basis of strong evidence of effectiveness, the Task Force recommends early childhood home visitation for prevention of child abuse and neglect in families at risk for maltreatment, including disadvantaged populations and families with low-birthweight infants. Compared with controls, the median effect size of home visitation programs was a reduction of approximately 40% in child abuse or neglect. Benefit was found whether the outcome was directly assessed in terms of reported abuse or neglect or indirectly assessed as reported injury. The only study that assessed the effects of home visitation on out-of-home placement indicated a small nonsignificant increase associated with home visitation (the desired result would be a decrease in out-of-home placement). Effect sizes (and the benefits of home visitation in prevention of child abuse or neglect) may actually be greater than reported here because the presence of the home visitor increases the likelihood that abuse or neglect will be observed. This likelihood is indicated by the findings from two studies reviewed (24,25) and introduces a bias against the hypothesis that home visitation reduces abuse or neglect (26). Stratified analyses provide information that might be useful in program design. Programs delivered by professional visitors (nurses or mental health workers [with either post--high school education or experience in child development]) yielded more beneficial effects than did those delivered by paraprofessionals. Programs delivered by nurses demonstrated a median reduction in child abuse of 48.7% (interquartile range: 24.6%--89.0%); programs delivered by mental health workers demonstrated a median reduction in child abuse of 44.5% (interquartile range not calculable). For paraprofessional visitors, effects were mixed: the median reduction in child abuse was 17.7%, but the variability of the findings is reflected in the interquartile range of -41.2%--65.7%. In programs using paraprofessionals, beneficial effects were consistently evident only when programs were carried out for >2 years. No additional benefit of multicomponent home visitation programs over single component programs was apparent. Time of initiation of programs (i.e., pre- or postnatally) did not affect the reduction of subsequent child maltreatment. Evidence from the single study of the effects of home visitation on partner violence (23) indicated that home visitation might not prevent child maltreatment in the presence of ongoing partner violence. The studies on which these conclusions are based are listed (Table). The only available cost-benefit analysis of a nurse home visitation program to reduce child maltreatment was based on

a limited, government perspective (i.e., including only those costs and benefits incurred by the government)

(27). In the whole study sample, costs exceeded economic benefits directly

attributable to reduced child maltreatment services by $3,000

per family. Including benefits beyond those of the government, such as averted health-care costs, productivity losses, and

other costs to the victim, is likely to result in greater net benefits. Program cost estimates --- largely dependent upon frequency of home visits and program duration --- ranged from $958 to $8,000 per family (in 1997 dollars). In the study subsample of low-income mothers, the analysis showed a net benefit of $350 per family (in 1997 dollars).

Most systematic reviews for the Community

Guide acknowledge the need for additional research, either to answer

questions posed by the review findings or to generate enough information on which to base findings. When the findings indicate

that evidence is insufficient to determine effectiveness, as is the case for much of the current review, the need

for a research agenda is

particularly great. The team has developed such an agenda, and will publish it, along with a full review of the evidence, in

a supplement to the American Journal of Preventive

Medicine.

Given the substantial burden of child maltreatment in the United States, and the importance of this problem both from public health and societal perspectives, the Task Force saw the need to specifically review the effectiveness of home visitation programs in reducing this and other forms of violence. The finding that these programs are effective in reducing child abuse and neglect should be relevant and useful in various settings. The Task Force recommendation supporting early childhood home visitation interventions for prevention of child abuse and neglect in families at risk of maltreatment can be used to support, expand, and improve existing home visitation programs, and to initiate new ones. In selecting and implementing interventions, communities should carefully assess the need for such programs (e.g., the burden of child maltreatment) and clearly define the target populations. Home visitation programs included in this review were generally directed to those populations and families believed to benefit most from common program components, such as support in parenting and life skills, prenatal care, and case management. Target populations included teenage parents; single mothers; families of low socioeconomic status; families with very low birthweight infants; parents previously investigated for child maltreatment; and parents with alcohol, drug, or mental health problems. The population that might benefit is large. For example, in 1999, approximately 33% of the 4 million births in the United States were to single mothers, 12.2% were to women aged <20 years, and 22% were to mothers with less than a high school education; 43% of births --- approximately 1.7 million --- were to mothers with at least one of these characteristics (B. Hamilton, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, personal communication, 2002). Studies included in this review were conducted in a variety of geographic locations in the United States and Canada and in populations with various ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The available evidence on the effectiveness of home visiting programs of sufficient duration indicates benefit for population subgroups in greatest need, provided that appropriate care is taken to tailor programs to local circumstances. Because no study reviewed assessed the effectiveness of home visitation in preventing violence in the general population, the broader applicability of these programs (e.g., to the general population) is uncertain. Public health professionals and policy makers should carefully consider the attributes and characteristics of the particular program to be chosen for implementation. Given the heterogeneity of home visitation programs in the United States, which differ in focus, curricula, duration, visitor qualifications, and target populations, no single optimal, effective, and cost-effective approach could be defined for the multiplicity of possible outcomes, settings, and target populations. However, the robust findings across a spectrum of program characteristics increase confidence that these programs can be effective in a range of circumstances and reduce concern that effectiveness hinges on particular characteristics of one intervention or one context. The Task Force found insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of early childhood home visitation in preventing violence by visited children and between adults. This conclusion does not imply that the intervention is ineffective in preventing these outcomes. Rather, the finding reflects a lack of enough high-quality studies with long enough follow-up periods to make a determination. These areas merit further research. This review considered only studies that evaluated violent outcomes. Home visiting may also affect other outcomes. Other studies have reported many other desirable outcomes of early home visitation (11,28), including health benefits for premature, low birthweight infants and for disabled and chronically ill children as well as long-term benefits, including reductions in need for public support of visited mothers, particularly single mothers of low socioeconomic status. However, all home visiting programs are not equal. Some are narrowly focused, oriented, for example, only toward improving vaccination coverage (29). Others might influence a broader range of outcomes. Program selection and design should consider the range of options relevant to the particular communities. To meet local objectives, recommendations and other evidence provided in the Community Guide should be used in the context of local information --- resource availability; administrative structures; and the economic and social environments of communities, neighborhoods, and health-care systems. In conclusion, this review, along with the accompanying recommendation from the Task Force on Community

Preventive Services, should prove a useful and powerful tool for public health policy makers, for program planners and implementers, and for researchers. It may help to secure interest, resources, and commitment for implementing these interventions, and

will

provide direction and scientific questions for additional empirical research in this area, which will further improve

the effectiveness and efficiency of these programs.

In addition to the early childhood home visitation intervention reviewed in this report, reviews have been completed for eight firearms laws (30), and for therapeutic foster care to prevent violence. Reviews of several other violence prevention interventions are pending or under way, including those on the treatment of juveniles as adults in the justice system and on school-based social and emotional skill learning programs. Community Guide reviews are prepared and released as each is completed. Findings from systematic reviews on vaccine-preventable diseases, tobacco-use prevention and reduction, motor vehicle occupant injury, physical activity, diabetes,

oral health, and the social environment have already been published. A compilation of systematic reviews will be published in

book form in 2004. Additional information regarding the Task Force, the Community Guide, and a list of published

articles is available on the Internet at

http://www.thecommunityguide.org.

* At the June 2002 meeting of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services, new terminology was adopted to reflect the findings of the Task Force. Instead of being referred to as "strongly recommended" and "recommended," such interventions are now referred to as "recommended (strong evidence of effectiveness)" and "recommended (sufficient evidence of effectiveness)," respectively. Similarly, the finding previously referred to as "insufficient evidence" is now more fully stated: "insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness." These changes were made to improve the clarity and the intent of the findings. † Members of the consultation team for the systematic reviews of violence prevention interventions were Laurie M. Anderson, Ph.D., CDC, Olympia, Washington; Carl Bell, M.D., Community Mental Health Council, Chicago, Illinois; Red Crowley, Men Stopping Violence, Atlanta, Georgia; Sujata Desai, Ph.D., CDC, Atlanta, Georgia; Deborah French, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, Colorado; Darnell F. Hawkins, Ph.D., J.D., University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois; Danielle LaRaque, M.D., Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York; Barbara Maciak, Ph.D., CDC, Detroit, Michigan; James Mercy, Ph.D., CDC, Atlanta, Georgia; Suzanne Salzinger, Ph.D., New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York; Patricia Smith, Michigan Department of Community Health, Lansing, Michigan. § Established Market Economies as defined by the World Bank are Andorra, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bermuda, Canada, Channel Islands, Denmark, Faeroe Islands, Finland, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Greenland, Holy See, Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Italy, Japan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, San Marino, Spain, St. Pierre and Miquelon, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. ¶ These databases can be accessed as follows: Medline: http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/PubMed; EMBASE: DIALOG http://www.dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/search/database/embase; ERIC: http://www.askeric.org/Eric/; NTIS: DIALOG http://www.dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://grc.ntis.gov/ntisdb.htm; PsycInfo: DIALOG http://www.dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.apa.org/psycinfo/products/psycinfo.html; Sociological Abstracts: DIALOG http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.csa.com/detailsV5/socioabs.html; NCJRS: http://abstractsdb.ncjrs.org/content/AbstractsDB_Search.asp; CINAHL: DIALOG http://www.dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.cinahl.com/wpages/login.htm. Table Return to top. Box  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/29/2003 |

|

|||||||

This page last reviewed 9/29/2003

|