Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Outbreak of 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) at a School --- Hawaii, May 2009

The first cases of 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza were reported by CDC on April 21, 2009 (1). Twenty-one days later, on May 12, the Hawaii Department of Health (HDOH) confirmed two pandemic H1N1 cases from the same school in Oahu. One case was in an 8th-grade student and the other in a 3rd-grade teacher. HDOH initiated an investigation to determine the extent of transmission at the school and among household contacts, and to help establish appropriate control strategies. This report summarizes the results of the investigation, which detected an outbreak of pandemic H1N1 cases at the school over the ensuing 3 weeks. A total of 16 cases were identified; all patients recovered with no hospitalizations or deaths. HDOH, the school, and the Hawaii Department of Education (HDOE) instituted an education campaign asking students and employees to stay home if ill. After consulting with HDOH, school officials decided not to close the school; the outbreak ended after 19 days. This outbreak represented the first documented community transmission of pandemic H1N1 virus in Hawaii. The investigation contributed to the early understanding of the epidemiology of H1N1 influenza in Hawaii (e.g., that risk factors for infection would not be restricted to mainland or foreign travel) and the likely role that endemic transmission would play. Influenza activity in schools can serve to inform local public health officials of changing disease patterns, especially early in an epidemic.

HDOH conducts routine, year-round influenza surveillance, including participation in national laboratory surveillance, an outpatient influenza-like illness (ILI) surveillance network (ILINet), and pneumonia and influenza mortality surveillance, and uses the ILI case definition (i.e., illness with fever (temperature of ≥100°F [≥37.8°C]) and cough or sore throat in the absence of another known cause) (2). In Hawaii, laboratory-confirmed influenza and influenza outbreaks are reportable. Schools are required to report when absentee rates attributable to any illness exceed 10% of the student body. The majority of school reporting has been for ILI-related absenteeism, so HDOH incorporates school reporting for ILI-related absenteeism into influenza surveillance. During early May 2009, Hawaii sentinel physicians reported that the ILI rate in Hawaii was higher than the national rate (2.4% versus 1.7%, respectively) (3). Hawaii identified its first confirmed case of pandemic H1N1 on April 29, 2009. HDOH subsequently requested that all persons with ILI symptoms seek medical care and health-care providers test all such patients for influenza by collecting nasopharyngeal specimens for reverse transcription--polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Positive specimens were submitted to HDOH for influenza subtyping by RT-PCR using CDC-approved primers. HDOH advised the public that persons experiencing symptoms consistent with influenza stay home from school/work for 7 days or 24 hours after fever resolution, whichever was longer (consistent with CDC recommendations at that time). A total of 42 confirmed cases, all associated with U.S. mainland travel, were identified before the school outbreak.

The school, a public Hawaiian immersion school enrolling 353 day students, comprises two adjacent campuses, one for K--8th grades (enrollment 235) and the other for 9th--12th grades (enrollment 118). Students reside in communities throughout Oahu, most riding school buses to campus. A school assembly is held twice a week. All students share one library, computer laboratory, and cafeteria. Only middle school students (7th and 8th grades) share common classes and participate together in daily athletics.

The initial two school cases of pandemic H1N1 were identified in an 8th-grade student and a 3rd-grade teacher on May 12. Their ILI onsets were May 1 and 7, respectively. The source of their infections is unknown; neither traveled out-of-state in the 10 days before onset. HDOH immediately alerted the HDOE superintendent. The 8th-grade student experienced ILI onset on May 1 and continued attending school. Although his symptoms appeared to improve after 2 days, he reported fever (102.0°F [38.9°C]) recurrence 4 days after onset. A nasopharyngeal specimen was obtained for influenza RT-PCR testing on May 8. The 3rd-grade teacher visited her physician on May 8 (1 day after onset), and a nasopharyngeal specimen was obtained for influenza RT-PCR testing; she did not attend school after illness onset during school hours but did go in to school on a weekend day when school was not in session. Both specimens were reported positive for 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus on May 12. On May 13, HDOH met with school staff to discuss mitigation options of school closure or continued self-isolation of other possible cases. The same day, HDOE provided students with a letter informing parents of the outbreak. On May 14, HDOH issued a press release reiterating the recommendation to stay home if ill. Per HDOH recommendations, HDOE decided to close the school only if a marked increase in hospitalizations or influenza-associated complications occurred or if school operations were affected by absenteeism. Neither of these conditions were met; the school did not close during this outbreak.

On May 12, HDOH launched an investigation to determine the sources of infection and extent of transmission. Confirmed cases, defined by laboratory identification of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus RNA by RT-PCR from a nasopharyngeal specimen, were ascertained by active and passive surveillance. HDOH interviewed the two initial patients and the parents of all students in the teacher's class. Continuing daily through June 4, the end of the school year, students were questioned about ILI symptoms, and the school health aide reported these students to HDOH. HDOH telephoned parents of ill students each day to identify any household contacts experiencing ILI symptoms and called through 7 days after onset of the last identified case in each household. All persons with ILI illness were interviewed and asked to undergo influenza testing. Interviewers used a standard questionnaire to collect demographic information, symptoms, medical history, clinical management information, and outcomes data. HDOH performed nasopharyngeal swabs for any person without health-care access.

Passive surveillance comprised daily review of HDOH pandemic H1N1 laboratory results. HDOH interviewed any person with confirmed pandemic H1N1 infection and a school affiliation. Household contacts with ILI also were interviewed and asked to undergo influenza testing.

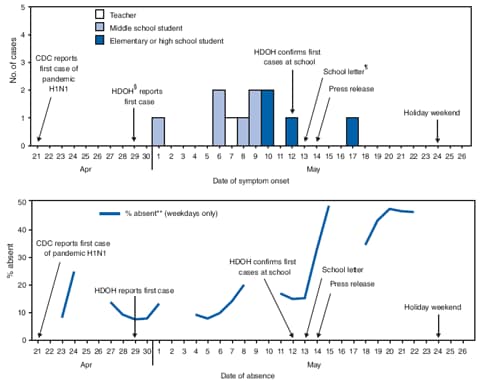

During May 12--26, a total of 16 confirmed cases affiliated with the school were identified; cases occurred in 10 students, one 3rd-grade teacher, and five household contacts of students (Table). The overall attack rate for confirmed cases among students was 2.8% (elementary school, 0.6%; middle school, 10.2%; and high school, 2.5%). Illness onset dates ranged from May 1 through May 17 (Figure). Median duration of reported fever was 6 days (range: 1--7 days). All persons recovered with no hospitalizations or deaths. Students with confirmed illness resided in six (18%) of 33 postal code areas on the island of Oahu. None traveled out of state in the 10 days before illness onset. Seven (44%) received seasonal influenza vaccine during the period October 2008--March 2009. Seven (44%) received antiviral medications.

HDOH reviewed student absentee rates before and during the outbreak. Overall absenteeism rates exceeded 10% on seven occasions during the 2 weeks before confirmation of the first case (Figure). Median daily absenteeism during April 23--May 13 was 13% (range: 7%--25%) for the entire school. This increased to 35% (range: 16%--49%) during the 2 weeks after schoolwide outbreak notification. The proportion of these absences attributable to ILI was unknown because reasons for absence were not collected. HDOH had not been notified of the increased school absenteeism before the recognition of the initial two laboratory-confirmed cases.

Reported by: SY Park, MD, MN Nakata, JL Elm, MS, MR Ching-Lee, MPH, R Rajan, MPH, CA Giles, H Hua, PhD, R Kanenaka, MS, MA Ando, MPH, JE Sasaki, MPH, C Le, MA, A Manuzak, MPH, M Wong, MS, Disease Outbreak Control Div, CA Whelan, PhD, R Ueki, R Sciulli, MSc, G Kunimoto, R Lee, MASCP, R Gose, MSPH, State Laboratories Div, Hawaii Dept of Health. T Chen, MD, Coordinating Office for Terrorism Preparedness and Emergency Response; MV Sreenivasan, MD, EIS Officer, CDC.

Editorial Note:

This school outbreak provided the first evidence of community transmission of pandemic H1N1 influenza in Hawaii. The source of infection for the initial cases was never identified, and whether undetected infections occurred at the school before the initial cases were identified is unknown. Student absenteeism data suggest possible disease activity before May 13, although this cannot be linked directly to ILI. The fact that the middle school students experienced the highest attack rate (10.2%) among all groups suggests that shared classrooms and activities among this group contributed to transmission.

In accordance with CDC guidance at the time (4), HDOH did not recommend school closure because routine school operations remained unaffected, the percentage of confirmed ill students was low, and recognized illnesses did not require hospitalization. Based on an estimated incubation period of 1--7 days for pandemic H1N1 infection (5), most cases in this outbreak resulted from exposure before HDOH initiated its investigation on May 12. No additional confirmed cases associated with this school were identified from May 19 to the scheduled summer closure on June 4, suggesting that transmission had ended. Asking students and staff to stay home if experiencing ILI symptoms possibly led to the increased absenteeism rate after May 13 and might have facilitated ending the outbreak.

The investigation of this school outbreak found pandemic H1N1 infections among residents of different communities without history of travel and provided the first clear evidence of community transmission within Hawaii. Early in a pandemic, schools with a wide geographic catchment area might serve either to accelerate spread because students (especially young school children) are a well-documented source of community influenza transmission (6) or represent markers for more widespread community transmission. Outbreaks in such widely representative schools might alert public health officials of a change in epidemiology and therefore warrant adjusting surveillance practices. In Toulouse District, France, a school outbreak of pandemic H1N1 occurred in June 2009 among students without history of travel, which led public health officials to broaden their surveillance efforts and incorporate communitywide sentinel sites (7). Because of this school outbreak, HDOH recognized local transmission would likely contribute substantially to the epidemiology of pandemic H1N1 in Hawaii and alerted the public that mainland or foreign travel were no longer the only risk factors.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, the investigation likely underestimated the actual case number because it relied on ILI reports from school staff to initiate case finding and interviewing; however, no cases were identified after May 26 by the school or laboratory reporting. Second, this investigation could not identify additional cases among school-associated persons who had ILI onset outside of school, did not seek medical care or receive testing, and whose illnesses were not reported to HDOH. Finally, some household contacts with ILI were not tested because they were identified more than 7 days after illness onset (8).

Health authorities, in close collaboration with HDOE and school staff, conveyed unified advice for school exclusion of persons experiencing ILI, which might have helped contain this outbreak. Clear, ongoing communication between education and public health authorities is especially important because guidance on school closures and other policies are updated and revised regularly. For example, since the time of this investigation, the period a person should stay out of school/work if ill has been revised to 24 hours after fever resolution without antipyretics (9). Current CDC guidance for responding to influenza in K--12 grade schools during the 2009--10 school year includes ensuring students and staff stay home when ill, separating ill persons if they become ill at school, proper hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, and routine cleaning of common areas (10). The guidance also provides a framework for when to consider closing schools.

Acknowledgments

This report is based, in part, on contributions by Hawaii clinical commercial laboratories and the Hawaii Dept of Education.

References

- CDC. Swine influenza A (H1N1) infection in two children---southern California, March--April 2009. MMWR 2009;58(Dispatch):1--3.

- CDC. Flu activity & surveillance. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivity.htm. Accessed January 4, 2010.

- Hawaii Department of Health. Influenza surveillance report, May 3--May 16, 2009: MMWR week 18--19. Available at http://hawaii.gov/health/family-child-health/contagious-disease/influenza/Influenza%20Reports/Influenza%20Surveillance%20Weeks%2018-19%202009.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2009.

- CDC. Update on school (K--12) and child care programs: interim CDC guidance in response to human infections with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/K12_dismissal.htm. Accessed November 12, 2009.

- CDC. Swine origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infections in a school---New York City, April, 2009. MMWR 2009;58:470--2.

- Neuzil KM, Hohlbein C, Zhu Y. Illness among schoolchildren during influenza season: effect on school absenteeism, parental absenteeism from work, and secondary illness in families. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:986--91.

- Guinard A, Grout L, Durand C, Schwoebel V. Outbreak of influenza A(H1N1)v without travel history in a school in the Toulouse district, France, June 2009. Euro Surveill 2009;14(27).

- CDC. Interim guidance on specimen collection, processing, and testing for patients with suspected novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/specimencollection.htm. Accessed December 23, 2009.

- CDC. Recommendations for the amount of time persons with influenza-like illness should be away from others. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/guidance/exclusion.htm. Accessed December 23, 2009.

- CDC. CDC guidance for state and local public health officials and school administrators for school (K--12) responses to influenza during the 2009--2010 school year. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/schools/schoolguidance.htm. Accessed December 23, 2009.

|

What is already known on this topic? School-aged children have some of the highest reported rates of seasonal influenza infection, and early in the 2009 influenza pandemic A (H1N1), schools were among the first locations to experience large outbreaks. What is added by this report? This report describes the first school-associated outbreak in Hawaii, which was the first evidence for endemic transmission of H1N1 virus in the state. What are the implications for public health practice? Investigation of the outbreak helped the Hawaii Department of Health recognize the role that endemic transmission would play during the H1N1 epidemic in Hawaii. The epidemiology of the disease in schools can inform local public health officials of changing disease patterns, especially early in an epidemic. |

FIGURE. Number of confirmed cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1)* and total percentage of students who were absent during a school-associated outbreak, by date of symptom onset† and date of absence --- Hawaii, April 21--May 26, 2009

* Defined by laboratory identification of 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus RNA by reverse transcription--polymerase chain reaction from a nasopharyngeal specimen.

† Onset dates for five cases among household contacts not shown.

§ Hawaii Department of Health.

¶ Several parents kept healthy students home after the school letter went out on May 13, according to reports from school staff.

** Represents total percentage absent for the entire school (N = 353).

Alternative Text: The figures above show the number of confirmed cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) and total percentage of students who were absent during a school-associated outbreak in Hawaii, by date of symptom onset and date of absence, during the period April 21-May 26, 2009. The overall attack rate for confirmed cases among students was 2.8% (elementary school, 0.6%; middle school, 10.2%; and high school, 2.5%). Illness onset dates ranged from May 1 through May 17. The Hawaii Department of Health reviewed student absentee rates before and during the outbreak. Overall absenteeism rates exceeded 10% on seven occasions during the 2 weeks before confirmation of the first case.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 1/6/2010