Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication --- Nigeria, January 2008--July 2009

Although wild poliovirus (WPV) cases in Nigeria decreased from 1,129 in 2006 to 285 in 2007 (1,2), Nigeria had the world's highest polio burden in 2008, with 798 (48%) of 1,651 WPV cases reported globally, including 721 (74%) of 976 WPV type 1 (WPV1) cases. This report provides an update on progress toward polio eradication in Nigeria during 2008--2009 and activities planned to interrupt transmission. During 2008--2009, Nigeria was the source for WPV1 transmission to 11 countries and WPV type 3 (WPV3) transmission to four countries (3). In addition, transmission of circulating type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV2) has been ongoing since 2005 (4). WPV1 cases decreased 87%, from 574 during January--July 2008 to 73 for the same period in 2009. However, WPV3 cases rose approximately six-fold, from 51 during January--July 2008 to 303 during the same period in 2009, partly because of the increased emphasis on controlling WPV1. The decline in the proportion of children who have never received oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) in the highest- incidence northern states, from 31% in 2006 to 11% in the first half of 2009 indicates progress toward eradication. During 2008--2009, activities to accelerate polio eradication included use of mobile teams to vaccinate children not at home during supplemental immunization activities (SIAs), and efforts to increase political oversight and the engagement of community leaders. Sustained support of traditional, religious, and political leaders and improved implementation of SIAs will be needed to interrupt WPV and cVDPV2 transmission.

Immunization Activities

Nigeria relies on a combination of routine immunization services using trivalent OPV (tOPV, types 1, 2, and 3) and SIAs* to immunize children against polio. In 2008, national coverage of children by age 12 months with 3 routine immunization tOPV doses was reported at approximately 50%†; however, population-based surveys conducted during 2007--2008 found coverage with 3 tOPV doses <40% nationally, and <30% in northern states with high WPV incidence (5,6).

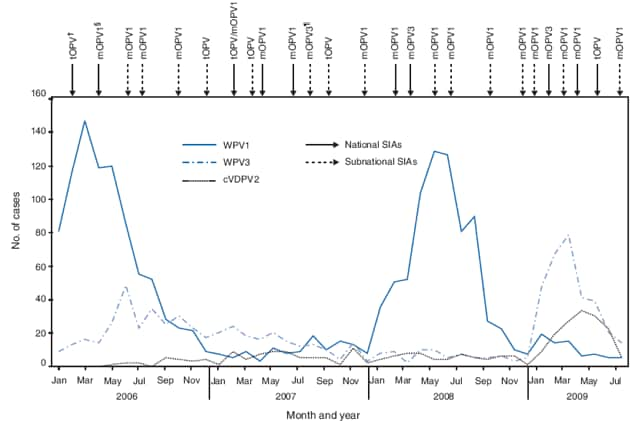

WPV1 is more likely to cause paralytic disease and have a wider geographic spread than WPV3. Monovalent vaccines are more effective against a given WPV type than is tOPV. Two national SIAs were conducted during 2008, one using monovalent OPV type 3 (mOPV3), and one using monovalent OPV type 1 (mOPV1). Three national SIAs were conducted during January--May 2009 using mOPV3, mOPV1, and tOPV consecutively (Figure 1). During January 2008--July 2009, mOPV1 was used in seven subnational SIAs, predominantly conducted in northern states.

Vaccination histories of children with nonpolio acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) are used to estimate OPV coverage among the target population of children aged 6--59 months. The proportion of children with nonpolio AFP reported to have never received an OPV dose (zero-dose children) in seven high-incidence states (≥0.8 confirmed WPV cases per 100,000 population during 2008) declined from 31% in 2006 to 11% during the first half of 2009 (Table). However, the proportion of zero-dose children remained high in 2009 in Kano (17%) and Zamfara (19%). By comparison, the proportion of zero-dose children in other northern (range: 3%--6%) and southern (2%) states was stable during 2006--2009 (Table). The proportion of children with nonpolio AFP with ≥4 reported OPV doses in high-incidence states increased from 13% in 2006 to 35% during January--July 2009.

AFP Surveillance

The polio eradication initiative in Nigeria relies on AFP surveillance to identify and confirm poliomyelitis cases by viral isolation; AFP surveillance is monitored using World Health Organization (WHO) targets for case detection and adequate stool specimen collection.§ The national nonpolio AFP detection rate among children aged <15 years was 5.7, 9.4, and 7.4 cases per 100,000 population in 2007, 2008, and January--July 2009, respectively. Nonpolio AFP detection rates meeting the target of at least two cases per 100,000 were achieved in all 37 states during 2007--2009, with 740 (96%), 752 (97%), and 714 (92%) of 774 local government areas (LGAs) achieving this target during 2007, 2008, and January--July 2009, respectively. Among AFP cases reported nationally, adequate stool specimens were collected for 92% of cases during 2007, and 94% of cases during 2008 and January--July 2009. During 2007--2009, Nigeria's 37 states reached the target of >80% of AFP cases with adequate stool specimens, as did 584 (75%) of 774 LGAs during 2007, 638 (82%) during 2008, and 651 (84%) during January--July 2009. The proportion of LGAs reaching the target for both surveillance indicators was similar in 2007 (75%) and 2008 (80%).

WPV and cVDPV Incidence

Among 1,174 WPV cases with onset during 2008 through July 2009, 836 (71%) occurred in children aged <3 years, 298 (25%) in children aged 3--5 years, and 31 (3%) in children aged >5 years. Overall, 1,152 (98%) cases involved children reported to have received <4 OPV doses, including 300 (26%) cases involving zero-dose children.

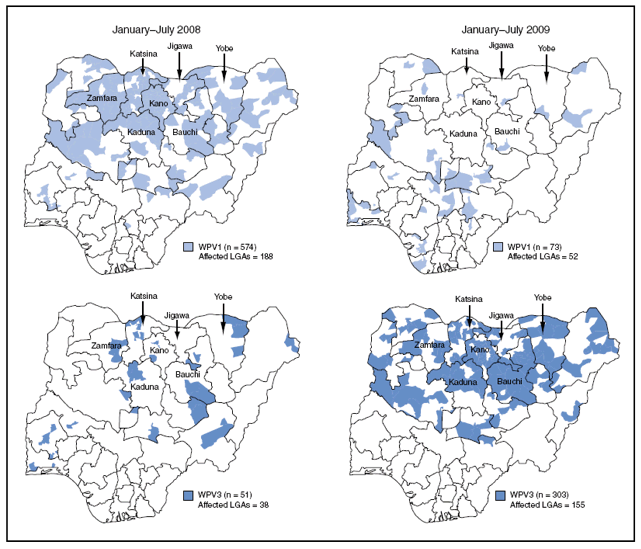

During 2008, of the 721 WPV1 cases reported, 570 (79%) occurred in the seven high-incidence northern states, 131 (18%) in other northern states, and 20 (3%) in southern states. Of 73 WPV1 cases reported with onset during January--July 2009, seven (10%) were in the high-incidence northern states and occurred primarily early in the year. The number of WPV1-affected LGAs during January--July 2009 was 52, compared with 188 during the same period in 2008 (Figure 2).

Among 77 WPV3 cases reported with onset during 2008, 42 (55%) occurred in the seven high-incidence states, 25 (32%) in other northern states, and 10 (13%) in southern states. Of 303 WPV3 cases reported with onset during January--July 2009, 232 (77%) occurred in the high-incidence states, 71 (23%) in other northern states, and none in southern states. The number of WPV3-affected LGAs during January--July 2009 increased four-fold to 155, from 38 during the same period in 2008 (Figure 2).

An outbreak of cVDPV2 in Nigeria began in 2005 (4). During 2008, 63 cVDPV2 cases were reported, increasing to 145 cVDPV2 cases reported with onset during January--July 2009. Despite the increase in cVDPV2 in early 2009, the monthly incidence declined after the tOPV SIA in late May, from 30 in May, to five in July (Figure 1).

Reported by: National Primary Health Care Development Agency and Federal Ministry of Health; Country Office of the World Health Organization, Abuja; Poliovirus Laboratory, Univ of Ibadan, Ibadan; Poliovirus Laboratory, Univ of Maidugari Teaching Hospital, Maidugari, Nigeria. African Regional Polio Reference Laboratory, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa. Vaccine Preventable Diseases, World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, Brazzaville, Congo. Polio Eradication Dept, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Div of Viral Diseases and Global Immunization Div, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC.

Editorial Note:

A loss of public confidence in OPV and suspension of SIAs in several northern states during 2003--2004 (7), along with long-standing insufficiencies in the health infrastructure and poor implementation of SIAs in many northern states has resulted in persistently high proportions of under- and unimmunized children in north Nigeria. A high incidence of WPV1 has occurred every 2 years in Nigeria (Figure 1). Although the lower WPV1 incidence observed in 2009 might be partly a result of natural immunity after high WPV1 incidence in 2008, the decline of WPV1 transmission in northern states to current historically low levels, the overall decrease in zero-dose children, and the low number of LGAs with WPV1 infections in northern states in 2009 suggest real improvements in the quality of SIAs.

The decrease in WPV1 case counts from 2008 through July 2009 followed the near-exclusive use of mOPV1 for SIAs. However, with this focus on controlling WPV1, the number of WPV3 cases rose. In addition, increased numbers of cVDPV2 in 2009 reflect the long-standing insufficient delivery of routine immunization services and the long interval (September 2007--May 2009) between tOPV SIAs; high coverage with tOPV (the only formulation to include type 2) is necessary to prevent emergence and transmission of cVDPV2. Recent decreases in monthly incidence of cVDPV2 suggest that the quality of the recent tOPV SIA improved, but further surveillance is needed to monitor trends. Recently developed bivalent OPV (bOPV, types 1 and 3) has been found to be superior to tOPV and as effective as mOPV in rates of seroconversion to WPV1 and WPV3 (8; WHO, unpublished data, 2009) and might be a better tool to interrupt transmission of both WPV serotypes. Strategic use of tOPV and bOPV (when available) during SIAs should optimize population immunity against all poliovirus serotypes. A subnational SIA in northern states using tOPV was conducted in August; additional SIAs are planned for October and November of 2009, and at least six national and subnational SIA rounds are planned for 2010.

The estimated percentage of zero-dose children has decreased substantially from 2006 to 2009 in most of the seven high-incidence states. If decreases experienced in the first half of 2009 continue, this will further indicate that progress is being made toward improving SIA implementation. However, 65% of target children in these high-incidence states remain undervaccinated (<4 doses). Based on experience in southern Nigeria and elsewhere, until the proportion of zero-dose children is below 10% in each state, and the proportion vaccinated with ≥4 doses is >80%, the risk remains that WPV transmission will persist or reemerge (9).

Nigeria often has been a source of virus introduction into polio-free countries (3). During 2008--2009 to date (as of October 13, 2009), 146 WPV1 cases resulted from virus genetically linked to northern Nigeria that spread to 11 previously polio-free neighboring countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone, and Togo) (3) and one linked cVDPV2 case occurred in Guinea (4). During this same period, 35 WPV3 cases resulted from virus genetically linked to northern Nigeria that spread to Benin, Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, and Niger. In addition, spread of virus in 2007 from Nigeria into Chad resulted in 59 WPV3 cases in Chad during 2008--2009 to date (3).

The 2008 World Health Assembly called for increased commitment and leadership within the Nigerian government to increase vaccination coverage (2,10). International partners¶ and the government have obtained greater commitment to polio eradication activities from political, religious, and traditional leaders at federal, state, and local levels. In February 2009, governors of all states convened an urgent meeting on child health, assisted by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and signed the Abuja Commitment to Polio Eradication in Nigeria, which defines specific goals and measurements of support by state and local government officials.** Recently, the government has prioritized activities to improve SIAs in the LGAs at highest risk for polio transmission; the results of those efforts will be monitored closely at state and national levels. If the support of traditional, religious, and political leaders can be sustained and expanded to further improve implementation of polio vaccination activities in these states and LGAs, more rapid progress can be made toward interrupting poliovirus transmission in Nigeria.

References

- CDC. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication---Nigeria, 2005--2006. MMWR 2007;56:278--81.

- CDC. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication---Nigeria, January 2007--August 12, 2008. MMWR 2008;57:942--6.

- CDC. Wild poliovirus type 1 and type 3 importations---15 countries, Africa, 2008--2009. MMWR 2009;58:357--62.

- CDC. Update on vaccine-derived polioviruses---worldwide, January 2008--June 2009. MMWR 2009;58:1002--6.

- World Health Organization/UNICEF. Review of national immunization coverage 1980--2009: Nigeria. Available at http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/data/nga.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2009.

- ICF Macro. Nigeria: standard DHS, 2008. MEASURE DHS (Demographic and Health Surveys), ICF Macro, Calverton, MD; 2008. Available at http://www.measuredhs.com/aboutsurveys/search/metadata.cfm?surv_id=302&ctry_id=30&srvytp=type. Accessed October 21, 2009.

- CDC. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication---Nigera, January 2004--July 2005. MMWR 2005;54:873--7.

- World Health Organization. Advisory Committee on Poliomyelitis Eradication: recommendations on the use of bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine types 1 and 3. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009;84:289--90.

- Jenkins HE, Aylward RB, Gasasira A, et al. Effectiveness of immunization against paralytic poliomyelitis in Nigeria. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1666--74.

- World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA61.1. Poliomyelitis: mechanism for management of potential risks to eradication. World Health Organization 61st World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland; May 2008. Available at http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/wha61-rec1/a61_rec1-part2-en.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2009.

* Mass campaigns conducted during a short period (days to weeks) during which a dose of OPV is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of previous vaccination history. Campaigns can be conducted nationally or in portions of the country (i.e., subnational SIAs).

† National coverage estimated based on administrative coverage, which uses official census numbers to estimate the number of targeted children.

§ AFP cases in children aged <15 years and suspected polio in persons of any age are reported and investigated, with laboratory testing, as possible poliomyelitis. WHO operational targets for countries at high risk for poliovirus transmission are a nonpolio AFP rate of at least two cases per 100,000 population aged <15 years at each subnational level and adequate stool specimen collection for >80% of AFP cases (i.e., two specimens collected at least 24 hours apart, both within 14 days of paralysis onset, and shipped on ice or frozen ice packs to a WHO-accredited laboratory and arriving at the laboratory in good condition).

¶ Include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Rotary International, KfW, World Bank, United Nations Childrens Fund (UNICEF), WHO, Canadian International Development Agency, CDC, U.S. Agency for International Development, government of Japan, and European Union.

** Available at http://www.polioeradication.org/content/publications/abujacommitments_04feb2009.pdf.

|

What is already known on this topic? Nigeria is one of four remaining countries that have never eliminated wild poliovirus (WPV) transmission, and has been the source of spread to multiple neighboring countries. What is added by this report? Although Nigeria had the world's highest polio burden during 2008 (798 [48%] of 1,651 cases), greater efforts to improve vaccination coverage among children appear to have reduced WPV type 1 substantially, from 574 cases during January--July 2008 to 73 during the same period in 2009. What are the implications for public health practice? Sustained support of traditional, religious, and political leaders and improved implementation of polio vaccination activities will be needed to interrupt poliovirus transmission in Nigeria. |

FIGURE 1. Number of laboratory-confirmed poliomyelitis cases, by wild poliovirus (WPV) type or circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) and month of onset, type of supplementary immunization activity (SIA),* and type of vaccine administered --- Nigeria, January 2006--July 2009

* Mass campaign conducted during a short period (days to weeks) during which a dose of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of previous vaccination history. Campaigns can be conducted nationally or in portions of the country.

† Trivalent OPV.

§ Monovalent OPV type 1.

¶ Monovalent OPV type 3.

Alternative Text: The figure above shows the number of laboratory-confirmed poliomyelitis cases, by wild poliovirus (WPV) type or circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 and month of onset, type of supplementary immunization activity (SIA), and type of vaccine administered in Nigeria from January 2006 through July 2009. WPV1 is more likely to cause paralytic disease and have a wider geographic spread than WPV3. Monovalent oral poliovaccines (mOPV) are more effective against a given WPV type than is trivalent OPV (tOPV). Two national SIAs were conducted during 2008, one using monovalent OPV type 3 (mOPV3), and one using monovalent OPV type 1 (mOPV1). Three national SIAs were conducted during January-May 2009 using mOPV3, mOPV1, and tOPV, consecutively.

FIGURE 2. Local government areas (LGAs) with laboratory-confirmed cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) and type 3 (WPV3) --- Nigeria, January--July 2008 and January--July 2009

Alternative Text: The figure above shows local government areas (LGAs) with laboratory-confirmed cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) and type 3 (WPV3) in Nigeria from January through July 2008 and January through July 2009. During 2008, of the 721 WPV1 cases reported, 570 (79%) occurred in the seven high-incidence northern states, 131 (18%) in other northern states, and 20 (3%) in southern states. Of 73 WPV1 cases reported with onset during January-July 2009, seven (10%) were in the high-incidence northern states and occurred primarily early in the year. The number of WPV1-affected LGAs during January-July 2009 was 52, compared with 188 during the same period in 2008.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 10/21/2009