|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

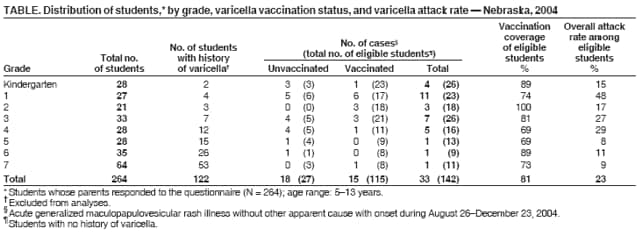

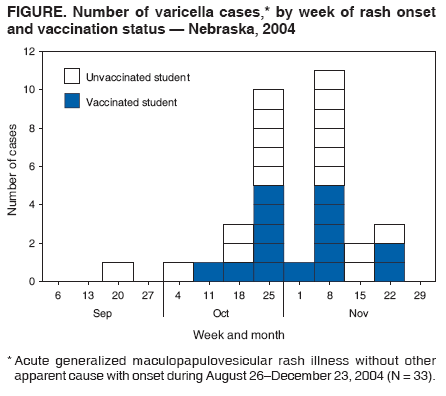

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Varicella Outbreak Among Vaccinated Children --- Nebraska, 2004On November 19, 2004, a school nurse notified the Nebraska Health and Human Services System (NHHSS) of a varicella outbreak in an elementary school (grades kindergarten through 7). In collaboration with local health department officials and CDC, NHHSS initiated a retrospective cohort study to determine the magnitude of the outbreak, assess vaccine coverage and effectiveness, and compare disease severity among vaccinated and unvaccinated students. This report summarizes the investigation and considers the suitability of school settings for case-based surveillance. The findings highlighted the importance of improving varicella vaccination coverage and implementing varicella vaccination school-entry requirements. Questionnaires were sent to parents of all students at the elementary school to determine history of varicella disease, varicella vaccination status, and underlying medical conditions. School immunization records were reviewed to confirm vaccination status for all students. In addition to receiving the questionnaires, parents of ill students were interviewed by telephone to ascertain the extent and nature of the disease. Specimens from skin lesions were solicited and tested for varicella-zoster virus (VZV). A case was defined as illness in a student with an acute generalized maculopapulovesicular rash without other apparent cause with onset during August 26--December 23, 2004 (i.e., during the fall school term). Cases were categorized as mild (<50 skin lesions), moderate (50--500 skin lesions), or severe (>500 skin lesions or any complications or hospitalization). No student with a history of varicella had the disease during the outbreak; therefore, students with a varicella history were excluded from vaccine effectiveness (VE) calculations (as were students whose parents did not return the questionnaire). VE was calculated as the proportional reduction in varicella attack rate between vaccinated and unvaccinated students using the following formula: VE = (1 - Relative Risk [RR]) ´ 100. The 283 students enrolled at the elementary school were divided into 15 classrooms. Parents of 19 (7%) of the 283 students did not return the questionnaire. Of the 264 respondents, 122 (46%) indicated that their child had a previous history of varicella. Of the remaining 142 students, 115 (81%) had been vaccinated. Illness in 33 students met the case definition. Specimens collected from skin lesions of seven students tested positive for VZV by polymerase chain reaction. The 33 patients ranged in age from 5 to 13 years (median: 8 years), and 20 (61%) were male. They represented all grades (kindergarten through 7) and 13 of 15 classrooms (Table). Results were grouped by grade to clarify vaccination coverage and varicella attack rates in the school. The outbreak started in late September and peaked in late October to early November (Figure). The index patient was an unvaccinated kindergarten student with rash onset on September 21. The child had a febrile illness and severe disease (i.e., >500 lesions and a secondary skin infection complication) and attended school for 2 days after rash onset. The source of the infection for the index case could not be identified. In nine of the 13 affected classrooms, the earliest rash onset was in an unvaccinated student. Three students became ill subsequent to illness onset in a sibling who attended the same school. Four secondary cases among nonstudent household members were identified (one child and three parents, all of whom were unvaccinated). All had rash onset within 2 weeks of exposure. Attack rates for vaccinated and unvaccinated students were 13% (15 of 115 students) and 67% (18 of 27 students), respectively. VE was 81% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 66%--89%) for preventing varicella of any severity and 93% (95% CI = 82%--97%) for preventing moderate to severe disease. Vaccinated students were significantly more likely to have milder disease (67% versus 11%) and fewer days of rash (5 versus 7.3) and to miss fewer days of school (3 versus 5.2) than unvaccinated students (p<0.01). After recognition of the outbreak, all parents at the school were notified of its occurrence, and parents of infected children were asked to keep their children at home until the end of the infectious period (i.e., 4--5 days after rash onset or until lesions formed crusts); NHHSS did not legally have the option of excluding unvaccinated students from school during the outbreak. In addition, teachers were provided information regarding recognition of mild cases that typically occur in vaccinated children. Although school and public health officials recommended vaccination of exposed, susceptible students at the Nebraska elementary school after recognition of the outbreak, no parents of the susceptible students agreed to administration of varicella vaccine to their children during the outbreak. Reported by: D Huebner, Hershey Elementary School, Hershey; S Smith, West Central District Health Dept, North Platte; T Safranek, MD, A O'Keefe, MD, Nebraska Health and Human Svcs System. A Lopez, MHS, M Marin, MD, D Guris, MD, Div of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (proposed); A Date, MD, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:Since licensure of varicella vaccine in the United States in 1995 and subsequent nationwide implementation of a varicella vaccination program, the country has experienced a dramatic decline in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths related to varicella (1,2). However, varicella outbreaks continue to occur among unvaccinated and vaccinated school children (3--6). This report corroborates the findings of other postlicensure studies, which indicated that the varicella vaccine is 80%--85% effective in preventing varicella of any severity and >95% effective in preventing severe varicella disease and that disease is generally milder in vaccinated persons. In 1999, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended establishing a varicella vaccination school-entry requirement (7). In August 2004, Nebraska implemented the requirement, applicable that year to students entering kindergarten and 7th grade and all out-of-state transfers.* The requirement has been extended to successive grades each subsequent year. In 2004, at the time of the outbreak, coverage in Nebraska was 82% among children aged 19--35 months. Some kindergartners and 7th graders at the outbreak school remained unvaccinated for religious reasons and were allowed to begin the 2004 fall term; Nebraska state law allows exceptions on religious and medical grounds. No parents of susceptible students agreed to administration of varicella vaccine to their children during the outbreak, likely because of a widespread belief among the parents that the vaccine was ineffective; the outbreak coincided with introduction of the varicella vaccination requirement, and some vaccinated students were contracting varicella. This report refutes the misconception that vaccination was ineffective and underscores the importance of investigating such outbreaks and educating parents about the value of varicella vaccination. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, information on history of varicella was obtained from parents and therefore subject to recall bias and reporting errors. Second, reliance on school staff members to notify NHHSS of potential cases might have led to incomplete case ascertainment. Third, reliance on parents for reports of rash or physicians for diagnosis might have resulted in overestimation or underestimation of VE; inability of school staff members or parents to recognize mild cases of disease also might have led to an overestimation of VE. In the United States, school-entry vaccination requirements have resulted in high and sustained vaccination coverage among school-aged children (8). By July 2006, the District of Columbia and all states except Idaho, Montana, Vermont, and Wyoming had implemented a varicella vaccination school-entry requirement. Varicella vaccination has reduced the risk for and severity of varicella disease among vaccinated students and warrants improving varicella vaccination coverage through broader school-entry requirements. In 2005, ACIP expanded its varicella vaccination school-entry requirement recommendations to include students from kindergarten through college (9). Gradually covering all grades through implementation of school-entry requirements will increase vaccination coverage and population immunity and continue to reduce varicella morbidity in schools and the community. To reduce additional virus transmission during outbreaks, in 2005, ACIP recommended a second dose of vaccine in outbreak settings for those who had received 1 dose of varicella vaccine (9). In addition, ACIP recently recommended a routine second dose of varicella vaccine for children aged 4--6 years.† During the 2004 Nebraska outbreak, because of the resistance by parents to vaccinating exposed susceptible students, NHHSS did not consider providing a second dose for previously vaccinated students; 13% of vaccinated children acquired varicella. Varicella-zoster immune globulin was not administered to any students. In 2002, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists recommended that by 2005, all states should establish case-based varicella reporting by using either statewide surveillance or surveillance in sentinel sites (10). Case-based surveillance systems facilitate timely recognition and control of outbreaks such as the Nebraska outbreak and help define the impact of varicella vaccination on the epidemiology of varicella disease. As demonstrated in this outbreak, schools are an ideal setting for varicella sentinel surveillance because of their readily available vaccination records and populations that can be surveyed easily. References

* Available at http://www.sos.state.ne.us/business/regsearch/Rules/Health_and_Human_Services_System/Title-173/Chapter-4.pdf. † Available at http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/pressrel/r060629-b.htm. Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 7/13/2006 |

|||||||||

|