|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

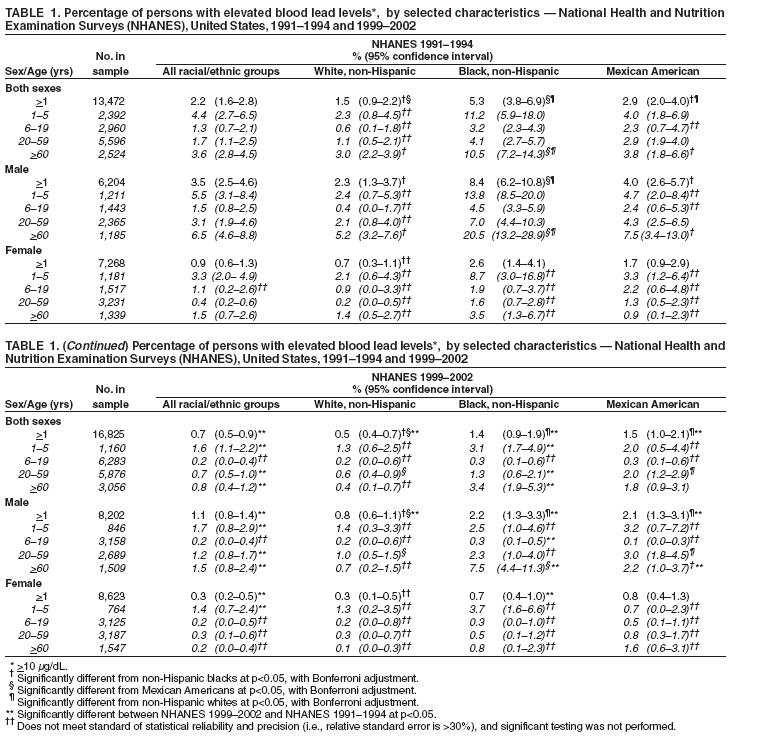

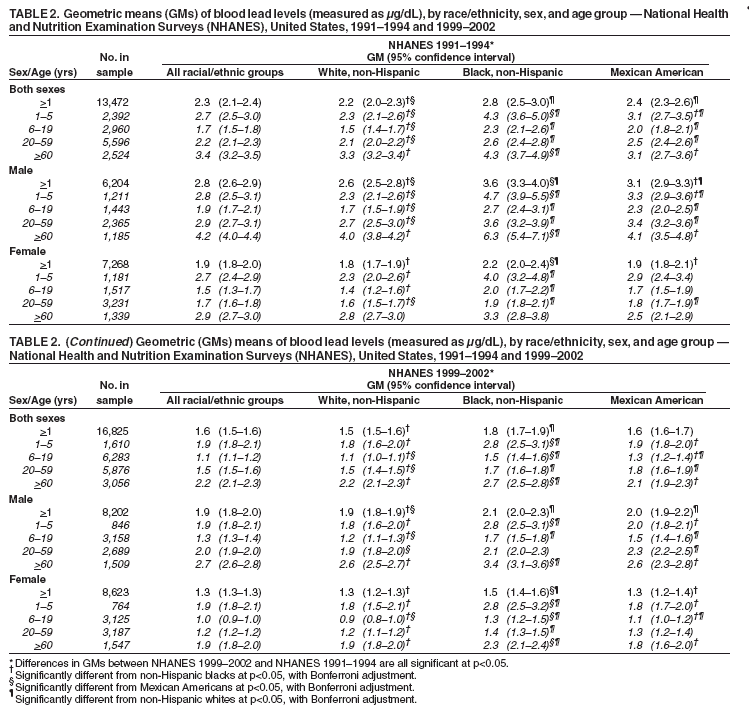

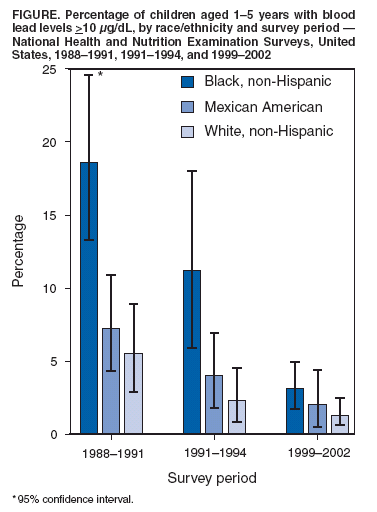

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Blood Lead Levels --- United States, 1999--2002Adverse health effects caused by lead exposure include intellectual and behavioral deficits in children and hypertension and kidney disease in adults (1). Exposure to lead is an important public health problem, particularly for young children (2). Eliminating blood lead levels (BLLs) >10 µg/dL in children is one of the national health objectives for 2010 (objective no. 8-11) (3,4). Findings of National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) from the period 1976--1980 to 1991--1994 reveal a steep decline (from 77.8% to 4.4%) in the percentage of children aged 1--5 years with BLLs >10 µg/dL (5,6). However, BLLs remain higher for certain populations, especially children in minority populations, children from low-income families, and children who live in older homes (5). This report updates estimates of BLLs in the U.S. population with the latest NHANES data, collected during 1999--2002. The findings indicated that BLLs continued to decrease in all age groups and racial/ethnic populations. During 1999--2002, the overall prevalence of elevated BLLs for the U.S. population aged >1 year was 0.7%. BLLs in non-Hispanic black children remained higher than in non-Hispanic white or Mexican-American children, although the proportion of BLLs >10 µg/dL in this population decreased (72%) since 1991--1994. Approximately 310,000 children aged 1--5 years remained at risk for exposure to harmful lead levels. Public health agencies should continue efforts to eliminate or control sources of lead, screen persons at highest risk for exposure, and provide timely medical and environmental interventions for those identified with elevated BLLs. NHANES is an ongoing series of cross-sectional surveys on health and nutrition designed to be nationally representative of the noninstitutionalized, U.S. civilian population by using a complex, multistage probability design. All NHANES surveys included a household interview followed by a detailed physical examination in a mobile examination center (MEC), at which time venous blood samples were obtained from persons aged >1 year. BLLs were measured by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrophotometry in the inorganic toxicology laboratory at CDC. Detailed analyses compared BLLs of 16,825 persons from the NHANES survey conducted during 1999--2002 with BLLs of 13,472 persons from the NHANES survey conducted during 1991--1994. Results were analyzed by age group, race/ethnicity (i.e., non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Mexican American), and low-income status (with the threshold determined by multiplying the U.S. Census Bureau poverty level threshold for the year of the interview by 1.3). Elevated BLLs were defined as BLLs >10 µg/dL for all ages. Geometric mean (GM) BLLs and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. All analyses used MEC sample weights to account for the unequal probability of selection, oversampling, and survey nonresponse. For 1999--2002, the overall prevalence of elevated BLLs for the U.S. population was 0.7% (Table 1), a decrease of 68% from 2.2% in the 1991--1994 survey. The largest decrease (72%) in elevated BLLs, from 11.2% to 3.1%, was among non-Hispanic black children aged 1--5 years, consistent with a previous decline from 1988--1991 to 1991--1994 (Figure). During the 1999--2002 survey period, children aged 1--5 years had the highest prevalence of elevated BLLs (1.6%), indicating that approximately 310,000 children in that age group remained at risk for exposure to harmful lead levels. Youths aged 6--19 years had the lowest prevalence of elevated BLLs (0.2%), although this estimate was not statistically reliable. Overall, by race/ethnicity, non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans had higher percentages of elevated BLLs (1.4% and 1.5%, respectively) than non-Hispanic whites (0.5%) (Table 1). Among subpopulations, non-Hispanic blacks aged 1--5 years and aged >60 years had the highest prevalence of elevated BLLs (3.1% and 3.4%, respectively). Although the prevalence of elevated BLLs among non-Hispanic black children was higher compared with children in the other two racial/ethnic populations, statistical power was not sufficient to examine these differences because of the small proportions and variability around the estimates. GM BLLs declined significantly (p<0.05) from the 1991--1994 survey period in all populations and subpopulations (Table 2). Overall, the GM BLL declined from 2.3 µg/dL in 1991--1994 to 1.6 µg/dL in 1999--2002. The highest GM BLLs in 1999--2002 were among children aged 1--5 years (1.9 µg/dL) and adults aged >60 years (2.2 µg/dL), and the lowest were among youths aged 6--19 years (1.1 µg/dL). Males had significantly higher GM BLLs than females, except among children aged 1--5 years, which is consistent with the 1991--1994 survey. By racial/ethnic group, among children aged 1--5 years, the GM BLL was significantly higher for non-Hispanic blacks (2.8 µg/dL), compared with Mexican Americans (1.9 µg/dL) and non-Hispanic whites (1.8 µg/dL). Among children aged 1--5 years from families with low income, the GM BLL also declined significantly, from 3.7 µg/dL in the 1991--1994 survey to 2.5 µg/dL in 1999--2002. Reported by: JG Schwemberger, MS, JE Mosby, MPH, MJ Doa, PhD, US Environmental Protection Agency. DE Jacobs, PhD, PJ Ashley, PhD, US Dept of Housing and Urban Development. DJ Brody, MPH, National Center for Health Statistics; MJ Brown, ScD, RL Jones, PhD, D Homa, PhD, National Center for Environmental Health, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that BLLs continue to decline in the United States, as measured by NHANES, the only survey providing national data on lead exposure. The GM BLL for the U.S. population aged >1 year decreased by 30% from 1991--1994 to 1999--2002, and the prevalence of elevated BLLs decreased by 68% overall and by 64% for children aged 1--5 years. Differences in proportions of elevated BLLs among children by race/ethnicity also were reduced, likely because of the substantial decline among non-Hispanic black children. However, the GM BLL for non-Hispanic black children remains higher than that for Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white children, indicating that differences in risk for exposure still persist. Exposure risk remains of particular concern in light of reported adverse health effects at BLLs <10µg/dL (7). The decline in BLLs in the United States has resulted from coordinated, intensive efforts at the national, state, and local levels beginning with efforts to remove lead from gasoline, food cans, and residential paint products (4). Beginning in 2003, CDC and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) required funded programs to develop formal plans to eliminate lead poisoning in their jurisdictions. Key components of these plans include coordination of activities by state, local, and nongovernmental organizations, linking BLL surveillance and Medicaid claims data to identify gaps in screening of populations at high risk, and eliminating lead paint hazards in housing, particularly in homes with more than one child with an elevated BLL. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, although NHANES is a nationally representative survey, the current design does not allow for estimates in smaller geographic areas or for identifying risk in certain subpopulations such as recent immigrants. Second, NHANES does not identify specific sources of lead exposure. Finally, the low prevalence of elevated BLLs does not allow stratification by more than one factor that might be related to exposure, such as race/ethnicity or age of residence. A critical factor in reducing BLLs in children has been the decline in the number of U.S. homes with lead-based paint, from an estimated 64 million in 1990 to 38 million in 2000 (8). This decline might be associated, in part, with federal appropriations to HUD of $700 million during fiscal years 1992--2002 for residential lead control in low-income, privately owned housing (9), and to investments in housing rehabilitation made by other government agencies and the private sector. Lead-control enforcement action by HUD, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Justice has resulted in approximately 200 on-site inspections and 30 settlements involving approximately 160,000 housing units nationwide (10). State and local governments have provided substantial additional funding for lead-poisoning--prevention activities and enforcement of local ordinances. However, an estimated 24 million housing units still contain substantial lead paint hazards, with 1.2 million of these units occupied by low-income families with young children (8). Findings in this report demonstrate progress toward achieving the national health objective for 2010 to eliminate elevated BLLs in children. Continued vigilance to identify remaining lead hazards and children at risk for lead exposure is necessary to meet this goal. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 5/26/2005 |

|||||||||

|