|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

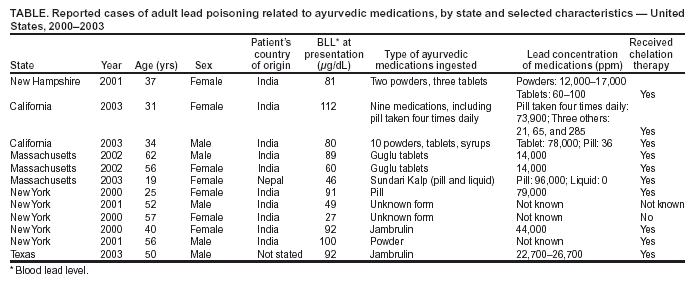

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Lead Poisoning Associated with Ayurvedic Medications --- Five States, 2000--2003Although approximately 95% of lead poisoning among U.S. adults results from occupational exposure (1), lead poisoning also can occur from use of traditional or folk remedies (2--5). Ayurveda is a traditional form of medicine practiced in India and other South Asian countries. Ayurvedic medications can contain herbs, minerals, metals, or animal products and are made in standardized and nonstandardized formulations (2). During 2000--2003, a total of 12 cases of lead poisoning among adults in five states associated with ayurvedic medications or remedies were reported to CDC (Table). This report summarizes these 12 cases. Culturally appropriate educational efforts are needed to inform persons in populations using traditional or folk medications of the potential health risks posed by these remedies. The first three cases described in this report were reported to CDC by staff at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center at Dartmouth Medical School, New Hampshire; the California Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program; and the California Department of Health Services. To ascertain whether other lead poisoning cases associated with ayurvedic medicines had occurred, an alert was posted on the Epidemic Information Exchange (Epi-X), and findings from the cases in California were posted on the Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance (ABLES) listserv. Nine additional cases were reported by state health departments in Massachusetts, New York, and Texas (Table). Case ReportsNew Hampshire. A woman aged 37 years with rheumatoid arthritis visited an emergency department (ED) with diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting of 6 days' duration. Tests revealed microcytic anemia, moderate basophilic stippling, and no identifiable source of blood loss. Her blood lead level (BLL) was 81 µg/dL (geometric mean BLL = 1.75 µg/dL for U.S. population aged >20 years [6]), and her zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP) concentration was 286 µg/dL (normal: <35 µg/dL [7]). She reported ingesting five different traditional medications (two powders and three tablets) obtained from an ayurvedic physician in India for her rheumatoid arthritis. Analysis of the two powders revealed 17,000 and 12,000 parts per million (ppm) lead, respectively, and 60--100 ppm lead in the three tablets. She began oral chelation therapy; 1 week after completion, her BLL was 35 µg/dL. Her two children, aged 6 and 7 years, had BLLs of 5 and 3 µg/dL, respectively. Two years later, the woman reported to her physician with joint symptoms from rheumatoid arthritis and was found to have microcytic anemia and a BLL of 64 µg/dL. She reported restarting ayurvedic medications 2 weeks previously. She agreed to stop taking the medications, and her physician decided against chelation therapy. California. A woman aged 31 years visited an ED with nausea, vomiting, and lower abdominal pain 2 weeks after a spontaneous abortion. One week later, she was hospitalized for severe, persistent microcytic anemia with prominent basophilic stippling that was not improving with iron supplementation. A heavy metals screen revealed a BLL of 112 µg/dL; a repeat BLL 10 days later was 71 µg/dL, before initiation of oral chelation therapy. A ZPP measurement performed at that time was >400 µg/dL. Her husband's BLL was 6 µg/dL. No residential or occupational lead sources were identified, but the woman reported taking nine different ayurvedic medications prescribed by a practitioner in India for fertility during a 2-month period, including one pill four times daily. She discontinued the medications after an abnormal fetal ultrasound 1 month before her initial BLL. Analysis of her medications revealed 73,900 ppm lead in the pill taken four times daily and 21, 65, and 285 ppm lead in three other remedies. Her BLL was 22 µg/dL when she was tested 9.5 months after the initial BLL testing. A man aged 34 years was evaluated twice in an ED for back pain and abdominal pain. A screen for heavy metals revealed a BLL of 80 µg/dL. He was hospitalized for chelation therapy and disclosed that he had been taking ayurvedic medications prescribed by a practitioner in India to increase fertility. He had discontinued use the previous day. The 10 preparations included pills, powders, and syrups, most of which were not labeled. He had taken one type of tablet once daily for 3 months; samples of one of these tablets contained 78,000 ppm lead. A second variety of pill contained 36 ppm lead. A home investigation revealed no other sources of lead. His BLL was 17 µg/dL when tested 7.5 months after the initial BLL test. Massachusetts, New York, and Texas. Nine additional cases were reported from Massachusetts, New York, and Texas (Table). The median age of patients was 52 years; five patients were female. The five women were taking the medications for arthritis (one), menstrual health (one), and diabetes (three). The four men were taking the medications for arthritis (one) and diabetes (three). Reported by: J Araujo, MD, AP Beelen, MD, LD Lewis, MD, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon; GG Robinson, MS, New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories; C DeLaurier, New Hampshire Dept of Health and Human Svcs. M Carbajal, B Ericsson, California Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program; Y Chin, MD, K Hipkins, MPH, California Dept of Health Svcs. SN Kales, MD, RB Saper, MD, Harvard Medical School; R Nordness, MD, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston; R Rabin, MSPH, Massachusetts Dept of Labor and Workforce Development. N Jeffery, MPH, J Cone, MD, C Ramaswamy, MBBS, P Curry-Johnson, EdD, New York City Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York; KH Gelberg, PhD, New York State Dept of Health. D Salzman, MPH, Texas Dept of Health. J Paquin, PhD, Environmental Protection Agency. DM Homa, PhD, Div of Emergency and Environmental Health Svcs, National Center for Environmental Health; RJ Roscoe, MS, Div of Surveillance, Hazard Evaluations, and Field Studies, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC. Editorial Note:Although the majority of cases of lead poisoning in adults result from occupational exposures, use of traditional or folk medications also can cause lead poisoning. In the United States, lead exposure in adults has decreased substantially during the preceding two decades because of removal of lead from gasoline and regulation of lead exposure in the workplace. Nevertheless, 10,658 cases of BLLs >25 µg/dL in adults (aged >16 years) were reported from the 35 states that provided data to the ABLES program in 2002 (1). Certain traditional or folk medications used in East Indian, Indian, Middle Eastern, West Asian, and Hispanic cultures contain lead and other adulterants (3). In this report, the majority of persons affected were of Asian Indian or other East Indian descent. Several ayurvedic and other traditional medications do not contain lead; however, lead content has ranged from 0.4 to 261,200 ppm in certain common ayurvedic preparations (8). Certain branches of ayurvedic medicine consider heavy metals to be therapeutic and encourage their use in the treatment of certain ailments. Symptoms of lead toxicity in adults often vary and are nonspecific; these include abdominal pain, fatigue, decreased libido, headache, irritability, arthralgias, myalgias, and neurologic dysfunction ranging from subtle neurocognitive deficits to a predominantly motor peripheral neuropathy to encephalopathy (9). The number and severity of symptoms typically increase as BLLs increase; however, the toxic effects of lead can occur without overt symptoms. In assessing patients with nonspecific, multisystemic symptoms, medical and public health professionals should consider lead toxicity in the differential diagnosis and request BLL testing. The finding of a high BLL without an obvious occupational or environmental source should elicit inquiries about traditional or folk medications as a potential source of exposure. Primary management of lead toxicity is source identification and exposure cessation. In adults, chelation therapy usually is reserved for patients with substantial symptoms or signs of lead toxicity or BLLs of >80 µg/dL (9). Culturally appropriate educational efforts are needed to inform persons of the potential health risks posed by these remedies, particularly in populations in which traditional or folk medication use is prevalent. For remedies known to contain lead or to be possibly adulterated with lead, educational materials should state the potential health effects. Young children and fetuses of pregnant women are at added risk for the toxic effects of lead, particularly because of the use of these products to treat infertility in women (10). Identification of the additional nine cases underscores the value of electronic health communications systems, such as listservs and Epi-X. These systems disseminate information quickly for geographically dispersed events that could be missed by routine surveillance systems. References

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 7/7/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 7/7/2004

|