|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

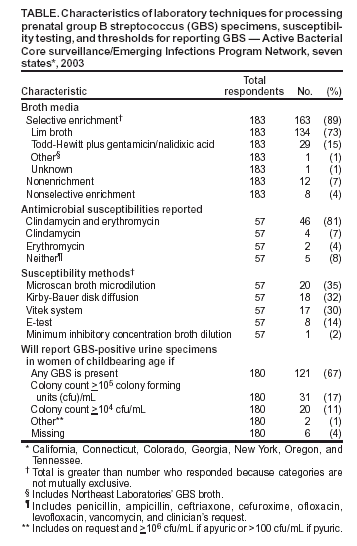

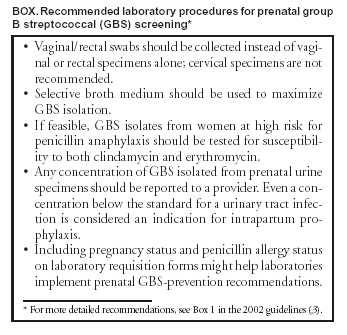

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Laboratory Practices for Prenatal Group B Streptococcal Screening --- Seven States, 2003In the United States, group B streptococcus (GBS) is the leading cause of serious bacterial infections in newborns (1). In 1996, consensus guidelines for use of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) to prevent perinatal GBS disease recommended either of two methods for identifying candidates for chemoprophylaxis: 1) late prenatal culture-based screening for GBS colonization or 2) monitoring of women intrapartum for particular risk factors associated with early-onset GBS disease (2). Evidence that culture-based screening was substantially more effective than the risk-based approach led to revised guidelines in 2002 recommending late prenatal GBS screening for all pregnant women (3,4). Although methods for isolation and identification of GBS from prenatal specimens remained the same as those recommended in 1996, the 2002 guidelines recommended that laboratories perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing on prenatal GBS isolates from women at high risk for penicillin anaphylaxis and clarified that laboratories should report the presence of any GBS in urine specimens from pregnant women. To assess laboratory adherence to recommendations in the 2002 guidelines, CDC's Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs)/Emerging Infections Program Network surveyed clinical laboratories about prenatal culture-processing practices in 2003. This report summarizes the results of that survey, which indicated that, although adherence to GBS isolation procedures was high, opportunities exist to improve implementation of recommendations related to antimicrobial susceptibility testing and GBS bacteriuria. During June--August 2003, a questionnaire was either mailed or administered over the telephone to personnel in all clinical laboratories in Georgia (n = 95 laboratories) and Connecticut (n = 32) and in selected laboratories in Tennessee (n = 40), New York (n = 34), California (n = 26), Colorado (n = 15), and Oregon (n = 11). Responses were received from 211 (83%) of 253 laboratories surveyed. The survey included questions regarding the anatomical source of specimens, requisition form requirements, media used for culture, antimicrobial susceptibility testing practices, and the threshold for reporting GBS in urine specimens. One set of responses was received from each laboratory; the response rate varied for each question. Certain response categories were not mutually exclusive. A total of 28 laboratories that did not perform onsite GBS testing were excluded from the analysis of questions regarding culture processing. Vaginal/rectal specimens were accepted for prenatal GBS screening in 195 (94%) of 207 laboratories; 12 (6%) laboratories accepted cervical specimens. These latter laboratories were affiliated primarily with small or rural hospitals. A total of 192 (98%) of 195 laboratories requested information on patient sex, and 194 (99%) requested information on patient age on requisition forms; fewer collected information on pregnancy status (33%) or penicillin allergy (22%). Of the 211 laboratories that responded, 183 (87%) processed GBS specimens onsite; the 28 laboratories that did not do onsite testing sent specimens to a reference laboratory, were located in hospitals that do not offer obstetric or gynecological services, or were small laboratories. A total of 163 (89%) of 183 laboratories that processed GBS specimens used the recommended selective enrichment broth media for GBS isolation (Table). Laboratories that did not use selective enrichment broth were affiliated with rural hospitals. A total of 100 (55%) of 182 laboratories performed susceptibility testing on GBS isolates only if requested by the provider; 27 (15%) performed susceptibility testing on all isolates, and 41 (23%) performed susceptibility testing on all isolates from women with a reported penicillin allergy. Five (3%) laboratories received few specimens but had the capacity to perform testing onsite or through a reference laboratory; 12 (7%) laboratories did not perform susceptibility testing at all. Among the 41 laboratories that performed susceptibility tests on the basis of a patient's penicillin allergy status, 27 (66%) requested allergy information on requisition forms. Among 57 laboratories that provided additional information about susceptibility testing, 46 (81%) reported susceptibilities for both clindamycin and erythromycin. Among 180 laboratories that receive prenatal urine specimens, 121 (67%) reported the presence of GBS in any level from urine specimens in women of childbearing age; 51 (28%) reported GBS growth from urine only if the bacterial count was >104 or >105 colony forming units (cfu)/mL. Reported by: A Reingold, MD, Univ of California, Berkeley; P Daily, MPH, A Grey, MS, Emerging Infections Program, California Dept of Public Health. S Burnite, T Crume, MSPH, N Haubert, Emerging Infections Program, Colorado Dept of Public Health. N Barrett, MPH, Emerging Infections Program, Connecticut Dept of Public Health. K Arnold, MD, J Schweitzer, MPH, Emerging Infections Program, Georgia Dept of Human Resources. G Smith, N Spina, MPH, New York State Dept of Health. P Cieslak, MD, K Stefonek, MPH, Oregon Dept of Human Svcs. B Barnes, Vanderbilt Univ School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee. K Cowgill, PhD, S Schrag, DPhil, Active Bacterial Core surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; S Chamany, MD, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:The recommendation that universal prenatal screenings (i.e., approximately 4 million per year) be performed for GBS colonization presents U.S. clinical laboratories with new challenges. Certain laboratories might be processing GBS specimens for the first time, whereas others might experience an increase in specimen volume. All laboratories should develop policies and procedures (Box to address the new recommendations related to antimicrobial susceptibility testing and reporting of GBS bacteriuria. Certain challenges can be addressed within the laboratory; others might require improved communication with prenatal-care providers. Use of vaginal/rectal swabs improves GBS isolation by 40%, compared with use of vaginal specimens alone; cervical cultures yield 40% fewer positive cultures than single vaginal swabs (5,6). Laboratories can inform providers who submit cervical swabs or vaginal-only swabs of current recommendations that they submit combined vaginal/rectal swabs. In addition, use of selective broth media increases GBS isolation by 50% when compared with nonselective media (7,8). Although, in this report, the proportion of laboratories using selective broth was much higher than in a survey after release of the 1996 guidelines (9), 11% of laboratories still were not using a selective broth medium. Because the majority of these laboratories were affiliated with small or rural hospitals, outreach activities (e.g., mailing guidelines and reporting survey results by telephone or mail) to these facilities might improve prevention implementation. GBS isolates remain universally susceptible to penicillin and ampicillin, the first-line agents for IAP. However, emerging resistance to clindamycin and erythromycin led to the recommendation of new prophylactic agents for women with penicillin allergy. Women at low risk for anaphylaxis should receive cefazolin; if feasible, GBS isolates from women at high risk for anaphylaxis should be tested for susceptibility to both clindamycin and erythromycin. Vancomycin is reserved for women at high risk for anaphylaxis with a clindamycin- or erythromycin-resistant isolate or when the susceptibility is unknown. Because susceptibility testing can guide the appropriate selection of a prophylactic agent, laboratories with the ability to perform susceptibility testing can play a key role in preventing overuse of vancomycin for GBS prophylaxis. Recommendations for treatment of women with GBS colonization who are allergic to penicillin pose challenges for clinicians and laboratories. Providers must obtain detailed penicillin allergy histories to assess whether patients are at low or high risk for anaphylaxis. Clinicians and laboratories must then establish a system for flagging which prenatal specimens require susceptibility testing. In this survey, laboratory requisition forms rarely included information on a patient's penicillin allergy. Instead, the majority of laboratories relied on providers to indicate the need for susceptibility testing. Certain laboratories opted to perform susceptibility testing on all prenatal GBS isolates, which is a more costly strategy but one that ensures test results are available for women allergic to penicillin. Seven percent of laboratories never performed susceptibility testing and might not have been aware of the 2002 revised guidelines. In addition, among laboratories that provided details on susceptibility testing, 19% did not report results for both clindamycin and erythromycin, highlighting an additional need for education on this issue. The presence of GBS bacteriuria in any concentration in a pregnant woman indicates the need for IAP because it is associated with increased risk for neonatal GBS disease. However, 17% of laboratories reported GBS from urine only if the bacterial count was >105 cfu/mL, the standard for urinary tract infections (10). Unless laboratories have a system for identifying which urine specimens come from pregnant women, low levels of GBS bacteriuria might go unreported. Only a third of laboratories in this survey included pregnancy status on requisition forms. Because most requisition forms include information on age and sex, certain laboratories might decide to report any GBS growth from urine from women of childbearing age. Improved strategies for communication of pregnancy status for urine specimens might reduce missed opportunities for detecting GBS bacteriuria during pregnancy. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, as part of the ABCs network, laboratories surveyed might have a heightened awareness of perinatal GBS prevention and might have received more education regarding laboratory practices; therefore, these results might overestimate national adherence to GBS-prevention recommendations. Second, methods of survey administration differed among ABCs sites, resulting in varying response rates for different questions. CDC offers information for clinical microbiologists (e.g., instructional photo gallery and slide sets), health-care providers, state health departments, and pregnant women at http://www.cdc.gov/groupbstrep. Copies of GBS prevention guidelines and health communication materials can be ordered from this website or from CDC's Respiratory Diseases Branch, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Mailstop C-23, 1600 Clifton Road, N.E., Atlanta, GA 30333. Acknowledgments The findings in this report are based in part on contributions by K Gershman, MD, Colorado Dept of Public Health. MZ Fraser, S Petit, MPH, Emerging Infections Program; J Hadler, MD, Connecticut Dept of Public Heath. M Farley, MD, Emory Univ School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. J Hatch, MT(ASCP), Oregon Dept of Human Svcs. W Schaffner, MD, Vanderbilt Univ School of Medicine, Nashville; A Craig, MD, Tennessee Dept of Health. N Anderson, MMSc, R Astles, PhD, E Rosner, EdD, G Westbrook, MT(ASCP), Div of Laboratory Systems, Public Health Practice Program Office; R Facklam, PhD, A Schuchat, MD, Active Bacterial Core surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. References

Table  Return to top. Box  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 6/17/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 6/17/2004

|