|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

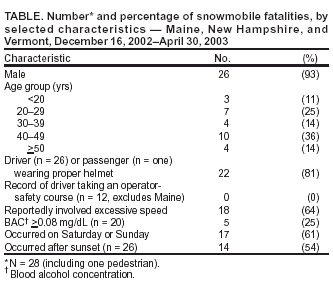

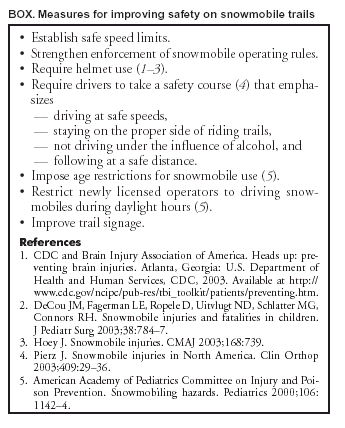

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Snowmobile Fatalities --- Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, 2002--2003During the 2002--2003 winter season in northern New England, 28 deaths in three states were associated with the use of snowmobiles, more than reported during any of the previous 12 winter seasons (Figure). The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services conducted a study to characterize these fatal injuries. This report describes the results of that study, which indicated that the leading contributors to snowmobile fatalities were excessive speed, inattentive or careless operation, and inexperience. Efforts to reduce snowmobile fatalities should focus on improving safety measures, including establishing speed limits, strengthening enforcement of snowmobile operating rules, and promoting safety education. A case was defined as a fatality involving a person either riding on or struck by a snowmobile in Maine, New Hampshire, or Vermont during December 16, 2002--April 30, 2003. Cases were identified by reviewing reports from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, and Vermont Department of Public Safety. The following three case descriptions summarize fatality reports from the three state agencies, based on investigations by enforcement officers. Case ReportsMaine. In early January 2003, driver A, a male aged 17 years, was operating a snowmobile with a 600 cubic centimeter (cc) engine when he collided with another snowmobile at approximately 4:30 p.m., 4 minutes after sunset. According to the investigative report, driver A was speeding when he crested a small rise on a state trail at the same time as driver B, who was traveling in the opposite direction. Driver A, who was wearing a helmet, was struck in the head by the oncoming snowmobile; he died from head injuries. Driver B was not injured. Vermont. In late January 2003, a man aged 45 years was operating a snowmobile with a 600 cc engine at 4:25 p.m., 20 minutes before sunset, when he attempted to make a right turn while traveling at high speed. The snowmobile overturned, throwing the driver onto the trail. The driver was wearing a helmet; his death was caused by blunt trauma to the chest and abdomen. New Hampshire. In late February 2003, a man aged 30 years was operating a snowmobile with a 700 cc engine on a frozen lake when he fell off his snowmobile at 5:00 p.m., approximately 30 minutes before sunset. Reportedly, the driver was speeding toward an open channel in an attempt to ride the snowmobile over open water, (i.e., "skimming.") The driver's blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was 0.06 mg/dL (New Hampshire's BAC limit for snowmobile operators is <0.08 mg/dL). The driver was not wearing a helmet. He struck his head on ice and fell into the water; death was caused by a basal skull fracture. Snowmobile Fatalities, Winter 2002--2003The 28 deaths associated with snowmobile use during the winter of 2002--2003 were the most reported annually by the three states during the previous 12 winter seasons (range: 6--24 deaths; median: 14 deaths). Sixteen (57%) of the 2002--2003 fatalities occurred in Maine, eight (29%) in New Hampshire, and four (14%) in Vermont. The fatality rate was 1.7 deaths per 10,000 registered snowmobiles in Maine, 1.2 per 10,000 registered snowmobiles in New Hampshire, and 1.0 per 10,000 snowmobiles with trail maintenance passes sold in Vermont. Of the 28 fatalities, 26 (93%) were drivers, one (4%) was a passenger, and one (4%) was a pedestrian. Twenty-six (93%) of the fatalities involved males (Table). The median age was 39 years (range: 15--58 years). Of the 20 fatalities for which BAC was tested, five (25%) involved BACs of >0.08 mg/dL. A total of 22 (81%) of the 27 riders fatally injured were wearing a helmet. None of the drivers in New Hampshire or Vermont had taken an operator safety course. Of the 21 snowmobiles with known engine size, 17 (81%) had >500 cc engines. Four (14%) of the 28 fatalities occurred in December, 12 (43%) in January, seven (25%) in February, four (14%) in March, and one (4%) in April; 17 (61%) of the fatalities occurred on Saturday or Sunday. Of the 26 fatal accidents with known time of occurrence, 14 (54%) occurred after sunset. Of the 25 fatalities with known weather condition, 18 (72%) occurred when the weather was clear, five (25%) when it was cloudy, and two (8%) when it was snowing. According to investigative reports of enforcement officers, 18 (64%) of the fatalities involved excessive speed (i.e., driving too fast for conditions); six (21%), inattentive or careless operation (e.g., driving on the wrong side of trails, attempting to jump embankments, and negotiating curves improperly); six (21%), inexperience; two (7%), mechanical problems; and one (4%), a heart attack; six (21%) fatalities involved more than one risk factor. Thirteen (46%) fatalities were caused by hitting fixed objects (e.g., trees, rocks, and chains across trails), four (14%) by head-on collisions with other snowmobiles, three (11%) by going through ice, three (11%) by going over an embankment, and five (14%) by other causes. Of the 13 fatalities caused by hitting fixed objects, nine (69%) occurred after sunset. Blunt trauma caused 23 (i.e., 14 head and neck, six chest and abdomen, and three other) (82%) of the deaths, two (7%) were caused by drowning, one (4%) by heart attack, and two (7%) were unknown. Reported by: T Acerno, New Hampshire Fish and Game Dept, Concord; A Pelletier, MD, New Hampshire Dept of Health and Human Svcs. J Johnson, Vermont Dept of Public Safety, Waterbury, Vermont. M Sawyer, Maine Dept of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, Augusta, Maine. L Ramsey, PhD, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:Snowmobile-related fatalities in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont during 2002--2003 were higher than during preceding years. The results of this study indicate that the primary causes of these fatalities were excessive speed, inattentive or careless operation, and inexperience. Excessive speed has been reported as a cause of snowmobile fatalities in Maine and New Hampshire (1,2). Engine sizes range from 250 cc to 1,000 cc, with snowmobiles traveling at speeds up to 110 mph. In Maine, no speed limits are posted on state trails; drivers must operate their machines at a "reasonable and prudent speed for the conditions." In New Hampshire, the speed limit on trails is 45 mph unless otherwise posted. In Vermont, the speed limit is 35 mph on public land; drivers must operate at "reasonable and prudent" speeds on private land, which comprises approximately 80% of the state's trail system. Measures for improving safety on snowmobile trails have been recommended (Box). All three states conduct free safety-training courses for snowmobile operators. Maine does not require drivers to take a safety-training course. New Hampshire requires persons aged <18 years without a valid driver's license to take a safety-training course. Vermont requires snowmobile operators born after July 1, 1983, to take a safety-training course. A total of 25% of those drivers tested had BACs of >0.08 mg/dL, less than percentages reported previously in Maine (41%; BAC >0.08 mg/dL) and New Hampshire (67%; alcohol used) (1,2). The reduction might be attributed to increased awareness and enforcement. In 1997, statewide strategic planning to improve snowmobile safety was initiated in Maine, and a Snowmobile Safety Awareness Committee was created in New Hampshire. The focus of these efforts is to increase safe riding, including educating snowmobile operators on the dangers of drinking and driving. The annual variation in snowmobile fatalities in the three states might be related to at least three factors. First, snowmobile use is dependent on weather conditions; winters with greater snowfalls and lower temperatures allow persons more opportunity to use snowmobiles. The cumulative snowfall for the 2002--2003 season in Concord, New Hampshire, was 89 inches, compared with an average of 45 inches during the previous 12 winter seasons. Second, the number of registered snowmobiles has increased over time, leading to an increase in the number of snowmobile operators, including inexperienced persons. Finally, the number of fatalities in the three states is small and might be unstable. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, data for some variables (e.g., reported speed and BAC) were not available for all fatalities. Second, risk factors could not be assessed from the data available. Strengthening enforcement of existing laws and increasing safety measures might reduce fatalities associated with snowmobiles. State and local officials should consider enacting additional measures to promote safety, especially those aimed at reducing speed on trails and educating operators on more cautious and attentive use of snowmobiles. Acknowledgments This report is based on contributions by K Boynton, Maine Dept of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. R Shults, PhD, Div of Unintentional Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; J Magri, MD, Div of Applied Public Health Training, Epidemiology Program Office, CDC. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top. Box  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 12/18/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 12/18/2003

|