|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

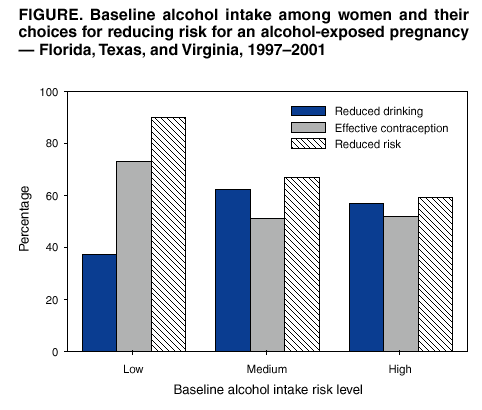

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Motivational Intervention to Reduce Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies --- Florida, Texas, and Virginia, 1997--2001Prenatal alcohol use is a threat to healthy pregnancy outcomes for many U.S. women. During 1999, approximately 500,000 pregnant women reported having one or more drinks during the preceding month, and approximately 130,000 reported having seven or more alcohol drinks per week or engaging in binge drinking (i.e., five or more drinks in a day) (1). These heavier drinking patterns have been associated with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders (ARND) (2). Lower levels of alcohol consumption (i.e., fewer than seven drinks per week) also have been associated with measurable effects on children's development and behavior (3,4). Although the majority of women reduce their alcohol use substantially when they realize they are pregnant, a large proportion do not realize they are pregnant until well into the first trimester and, therefore, might continue to drink alcohol during this critical period of fetal development. To reduce alcohol-exposed pregnancies, CDC initiated a multisite pilot study (phase I clinical trial) in 1997 to investigate the use of a dual intervention focused on both alcohol-use reduction and effective contraception among childbearing-aged women at high risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy (Project CHOICES) (5). This report describes the association between baseline drinking measures and the success women have achieved in reducing their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. The analysis compares the impact of the motivational intervention at 6-month follow-up on women drinking at high-, medium-, and low-risk drinking levels. The findings indicate that although 69% of the women in the study reduced their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy, women with the lowest baseline drinking measures achieved the highest rates of outcome success, primarily by choosing effective contraception and, secondarily, by reducing alcohol use. Women with higher baseline drinking measures chose both approaches equally but achieved lower success rates for reducing their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial of the motivational intervention is under way to further investigate outcomes of the phase I study. Reproductive-aged (18--44 years), sexually active, fertile women were included in the study if they reported risk drinking (i.e., more than seven drinks per week on average or having one or more binge-drinking episodes during the preceding 3 months) and using ineffective contraception. Ineffective contraception was defined according to the type of contraceptive method reported by the participant, and the failure to use that method in accordance with the published recommendations (6) without using an appropriate back-up method (7). Study participants were recruited from community-based settings with higher documented rates of women at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy, including a large urban jail (Texas); residential alcohol and drug treatment facilities (Texas); a gynecology clinic serving low-income women (Virginia); two primary care clinics serving low-income populations (Virginia and Florida); and media solicitation (Florida). Each participant provided written informed consent on forms approved by site-specific Institutional Review Boards and CDC's Institutional Review Board. Recruitment took place from spring 1999 to summer 2000. Of 2,384 women screened in Florida, Texas, and Virginia, 230 were eligible for the study; 190 (83%) consented to participate and were enrolled. Participants received a maximum of four motivational counseling sessions and one visit to a family planning provider. As part of the study, participants also completed an interview at enrollment and at 6-month follow-up to assess the impact of the brief intervention. At both times, methods of contraception were assessed along with the effectiveness of use. In addition, information was collected about drinking history, recent drinking, emotional distress, awareness of FAS and anti-drinking messages targeted to pregnant women, and sociodemographic characteristics. AUDIT (8), a screening instrument developed by the World Health Organization that incorporates questions about drinking (i.e., quantity, frequency, and binge drinking) and the consequences of drinking, was administered at baseline. The AUDIT instrument has been reported to be valid and reliable across different cultures, settings, and age groups (9). This test provided a range of scores from which categorical levels of risk drinking were developed. Scores were grouped into three drinking categories according to level of severity: low (1--7), medium (8--18), and high (19--40). The goals of the motivational interviewing sessions were to provide personalized feedback on the risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy, to motivate participants to change one or both of the target alcohol-use behaviors (i.e., decreasing alcohol intake to fewer than eight drinks per week and no binge drinking), to decrease the temptation to engage in risk drinking and increase confidence to avoid it, and to encourage the use of effective contraception through contraceptive counseling visits. Descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline demographic and risk characteristics of women included in the analysis. In addition, bivariate analysis and logistic regression were conducted to assess differences between the baseline and the post-intervention status of the target outcome behaviors. Of the 190 women enrolled in the study, approximately one third were from each site in Florida, Texas, and Virginia. Data about contraception use and drinking information were available both at enrollment and at 6-month follow-up interviews for 143 (75%) women. The majority (119) of study participants were members of racial/ethnic minorities (45% non-Hispanic black, 37% non-Hispanic white, 9% Hispanic, and 9% other), and the median age of participants was 31 years (range: 18--44 years); 147 (77%) reported having at least a high school education, and 121 (64%) reported annual incomes of <$20,000. Of the 190 women at baseline, 188 (99%) reported binge drinking on one or more occasions during the preceding 6 months, and 123 (65%) women reported frequent drinking. A total of 122 (64%) reported both drinking behaviors (binge and frequent drinking). The average baseline AUDIT score was 17 (range: 1--40). Scores of >8 indicate a strong likelihood of excessive alcohol use. A woman was considered not at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy at the 6-month follow-up if she had reduced drinking (i.e., fewer than eight drinks per week and fewer than five drinks on a day during the preceding 6 months), used effective contraception, or both. The association among baseline AUDIT scores and reduced drinking, effective contraception, and reduced risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy at 6-month follow-up documented different patterns (Figure). Women's success in reducing their alcohol consumption below the level defined as high risk varied by their AUDIT scores at baseline. Women with the lowest AUDIT scores at baseline were statistically less likely to reduce their risk drinking (11 [37%]) than women with medium and high scores (34 [62%] and 33 [57%], respectively, p<0.03). The proportion of women instituting effective contraception use was higher among women with the lowest AUDIT scores (22 [73%]), compared with women with medium (28 [51%]; p<0.05) and high (30 [52%]) scores. An inverse association was observed between AUDIT scores at baseline and reduced risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy at 6 months (p = 0.01) (Figure). Women with the lowest AUDIT scores were the most likely to reduce their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy (27 [90%]), compared with those with medium and high scores (37 [67%], p<0.03 and 34 [59%], p<0.005, respectively). Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between baseline AUDIT scores and reduced risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy in the presence of potential confounders (e.g., income, marital status, education, and age). The baseline AUDIT score was the strongest predictor for reduced risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. Therefore, women's baseline drinking levels influenced their choices of how to reduce their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy by either instituting effective contraception use, reducing risk drinking, or both. Reported by: MB Sobell, LC Sobell, K Johnson, Nova Southeastern Univ, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. MM Velasquez, PD Mullen, K von Sternberg, Univ of Texas-Houston Health Sciences Center, Houston, Texas. MD Nettleman, KS Ingersoll, SD Ceperich, Virginia Commonwealth Univ, Richmond, Virginia. Project CHOICES Intervention Research Group. J Rosenthal, RL Floyd, JS Sidhu, Div of Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC. Editorial Note:Fertile women who are sexually active, consume more than seven drinks per week or binge drink, and do not use effective contraception are at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy and having a child with lifelong impairments in intellectual, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning (4). Preventing FAS or ARND requires intervening not only with pregnant women but also with childbearing-aged women before conception. Brief interventions using motivational interviewing techniques are effective among childbearing-aged women in reducing harmful drinking patterns (10). Women in this study reduced their risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancy by reducing their alcohol consumption risk, increasing their use of effective contraception, or both. Among high-risk women overall, 69% were able to reduce their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. Project CHOICES differs from other intervention studies because it offers effective contraception use in addition to reduced drinking as a strategy for decreasing the risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. Although successful among all AUDIT score categories, this dual intervention had a differential impact on behavior change dependent on the participants' baseline alcohol use and experienced consequences of alcohol use (AUDIT score). Women with low AUDIT scores were more successful in reducing their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy at the 6-month follow-up visit (90%), mostly by increasing their use of effective contraception. In comparison, women with higher AUDIT scores were more successful in reducing their alcohol use than women with lower AUDIT scores but were less likely to adopt effective contraceptive use. Women with lower alcohol use patterns at baseline might not have perceived their alcohol use patterns as problematic but did respond to the message of effective contraception use to avoid an unintended prenatal alcohol exposure. Women with higher alcohol-use patterns might have been more sensitized to the potential problematic nature of their alcohol use and might have chosen to reduce drinking because of their desire to improve their overall health. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, sample sizes were not sufficient to assess the impact of rates of change of reduced risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy between and within the community-based settings. Although some sociodemographic differences were noted among the settings, rates of change for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy across sites were similar (65%--72%), as indicated in previous findings (5), suggesting that the impact of these site differences did not affect the study outcomes. Second, no control group was used, thus limiting the evaluation of the effectiveness of the intervention. Third, the study was based on self-reported alcohol drinking and contraception-use data. Therefore, some participants' reports of change might have been attributable to social desirability or wanting to please the study personnel. However, the accuracy of self-reports in alcohol treatment studies is comparable to that of biochemical validation or collateral reports (10). Providing an effective option for reducing the risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy to high-risk women who do not respond to strategies focusing on alcohol-use reduction is an important step for FAS prevention. To address the limitations of this study, a randomized controlled trial is under way to test the efficacy of this intervention and will include sufficient sample sizes to assess the impact of different settings on the intervention outcome. Until more definitive findings are available, this information might interest counselors, clinicians, and other public health providers concerned with the prevention of FAS and other prenatal alcohol-related conditions. References

Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 5/15/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/15/2003

|