|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

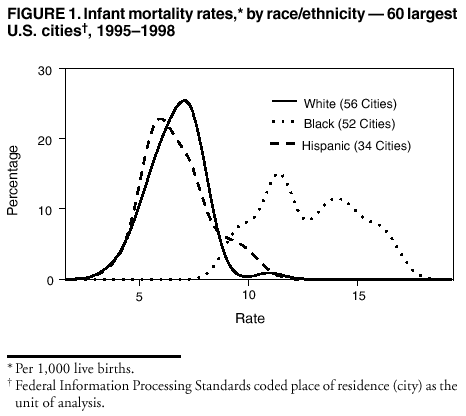

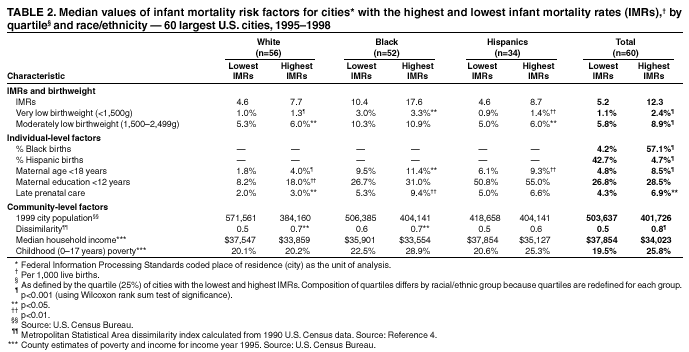

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Infant Mortality Rates --- 60 Largest U.S. Cities, 1995--1998During the 20th century, U.S. infant mortality rates (IMRs) declined by 90% (1); however, many of the largest U.S. cities continue to have high IMRs compared with national rates. Studies of U.S. infant mortality by region document persisting geographic disparities (2,3) and differences across racial/ethnic groups. This report highlights the wide disparities in the most recent overall race- and ethnicity-specific IMRs for the largest U.S. cities and describes key differences among those cities. The findings demonstrate the need to decrease infant mortality among blacks in U.S. cities. IMRs (number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births) were calculated by using the National Center for Health Statistics' Perinatal Mortality Data for 1995--1998. The numbers of infant deaths were obtained from linked birth- and death-certificate files, and the numbers of live births were obtained from corresponding birth-certificate files. Rates were based on the mother's race, ethnicity, and city of residence at time of birth by using Federal Information Processing Standards place-of-residence codes as units of analysis. Rates and numbers were reported for the 60 cities with 1990 populations >250,000. Rates for four cities meeting the population criteria---Cleveland, Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Oklahoma City---were not reported because >10% of their county infant deaths were not linked to birth certificates. Race- and ethnicity-specific rates were reported for non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic infants. Rates based on <20 infant deaths and rates for other racial/ethnic groups were not reported because the numbers of infant deaths among these groups were too low for meaningful analysis. Characteristics of cities in the highest quartile for IMRs were compared with those in the lowest quartile for each of the three racial/ethnic groups. Quartiles were defined based on the ranking of city IMRs. In addition to very low (<1,500g) and moderately low (1,500--2,499g) birthweight, individual- and community-level variables were considered. Individual-level variables were maternal race/ethnicity, late prenatal care (enrollment after the sixth month of pregnancy) or no prenatal care, low maternal education (<12 years), and birth to a teenage mother (maternal age <18 years). Community-level variables were population size, geographic region, segregation (determined by the index of dissimilarity, which measures the extent to which blacks and nonblacks inhabit different parts of a metropolitan area) (4,5), median household income, and childhood poverty. Metropolitan and county data were used when city data were not available. During 1995--1998, IMRs varied widely among the 60 largest U.S. cities (Table 1). Overall rates ranged from 4.5 to 15.4 infant deaths per 1,000 live births (median rate: 7.8). Non-Hispanic white IMRs were reported for 56 cities, non-Hispanic black IMRs for 52 cities, and Hispanic IMRs for 34 cities. IMRs vary by race/ethnicity (Figure 1); the median black IMR of 13.9 per 1,000 live births was substantially higher than both white and Hispanic IMRs (6.4 and 5.9, respectively). Black IMRs were 1.4--4.8 times higher than white IMRs in all 49 cities where both were reported. Wide differences also existed within each racial/ethnic group (Table 1). The city with the highest IMR in each racial/ethnic group had an IMR at least twice that of the city with the lowest IMR in that group. The wide black IMR distribution reflected the broad range of IMRs among black infants compared with Hispanic and white infants. The distribution of white IMRs showed higher rates in some cities (e.g., Norfolk's IMR was noticeably higher compared with other cities [11.6 deaths per 1,000 live births]). Similarly, the distribution of Hispanic IMRs showed higher rates in some cities (e.g., Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia). Cities with the highest IMRs tended to have a larger proportion of black births (median: 57.1%, range: 36.8%--82.4%) and a smaller proportion of Hispanic births (median: 4.7%, range: 0.9%--33.5%) (Table 2). Conversely, cities with the lowest IMRs tended to have a smaller proportion of black births (median: 4.2%, range: 0.7%--25.0%) and a larger proportion of Hispanic births (median: 42.7%, range: 7.1%--86.0%). Highest-quartile cities had more very low- and moderately low-birthweight infants, more births to teenage mothers, more late or absent prenatal care, and more racial segregation (4,5). Cities with higher IMRs were more commonly in the Midwest, Southeast, and Northeast, and those with lower IMRs were clustered in the Pacific West and West Central regions. Reported by: V Haynatzka, PhD, M Peck, ScD, CityMatCH, Univ of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska. W Sappenfield, MD, S Iyasu, MBBS, H Atrash, MD, Div of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; K Schoendorf, MD, National Center for Health Statistics; S Santibanez, MD, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:This report highlights considerable geographic, racial, and ethnic differences in IMRs in the largest U.S. cities. Because urban communities are targets for many local, state, and federal initiatives, reporting and comparing city-specific IMRs for understanding city-level differences in child health is important. Previous studies have examined factors related to black-white disparities in infant mortality. Infants with very low birthweight account for approximately two thirds of the black-white gap in infant mortality (6). Preterm delivery is associated with the deaths of infants with very low birthweight, demonstrating the need to reduce preterm births, particularly among black infants. Racial disparity in IMRs has not been explained fully by differences in socioeconomic status. Black infants born to college-educated parents have higher IMRs than white infants born to parents of similar educational background; this difference is attributed to a higher rate of very low birthweight (7). Education of the mother does not confer the same level of protection against infant mortality among black women as it does among white women, suggesting that a complex interaction of social, environmental, and biologic factors that are experienced uniquely by black women might account for the disparity. Racial segregation is an important macrolevel predictor of greater black-white infant mortality differences in 38 U.S. metropolitan statistical areas, independent of differences in median income (8). Despite higher poverty and lower education rates, Hispanic infants have higher birthweights and their IMRs approximate those of white infants. This finding is consistent with previous studies (9) and contradicts common assumptions about poor, underserved minority groups. Cultural practices, family support, selective migration, diet, and genetic heritage are possible contributing factors (9). Furthermore, U.S. Hispanics are a heterogeneous group, and IMRs are higher among Puerto Rican infants (10). In Philadelphia, 79% of Hispanic births were born to Puerto Rican mothers, possibly explaining the higher IMR in that city. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, accurate and consistent reporting of city of residence on birth and death certificates in some cities is problematic. To address this problem, many health departments geocode the mother's street address reported on the birth certificate and then aggregate to city and subcity boundaries. Although geocoding vital records might allow for the calculation of more accurate IMRs for some cities, especially those with a high percentage of correct address matches, not all urban health departments have that capability. Second, reporting requirements specify the rapid transmission of vital statistics data from states to CDC, not always allowing time for the inclusion of geocoded residences in the national vital statistics data files. The wide differences both within and among the racial/ethnic groups in this report suggest that city IMRs can be reduced further. Reducing national IMRs will require ongoing scientific research and partnerships with diverse community groups to identify culturally sensitive strategies. Efforts to eliminate IMR disparities in urban communities include CDC's Initiative on Eliminating Ethnic Health Disparities, Healthy People 2010; CDC's Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH 2010) project; and the Health Resources and Services Administration's Healthy Start Initiative. One city-driven initiative, the Perinatal Periods of Risk Practice Collaborative, has enlisted 14 U.S. cities to adopt the World Health Organization's Perinatal Periods of Risk Approach to monitor and investigate fetal and infant mortality. References

Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 4/18/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 4/18/2002

|