|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

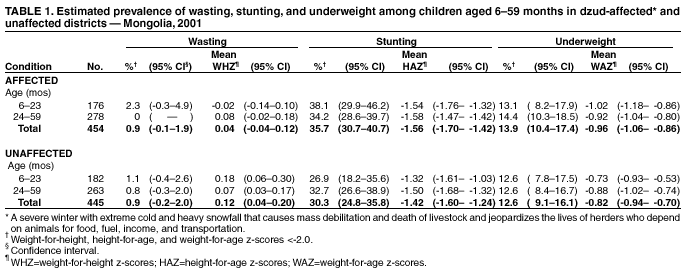

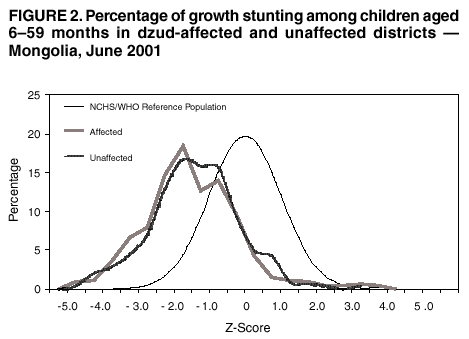

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Nutritional Assessment of Children After Severe Winter Weather --- Mongolia, June 2001During 1999--2001, Mongolia (2000 population: 2.7 million) experienced consecutive dzuds (i.e., a severe winter with extreme cold and heavy snowfall that causes mass debilitation and death of livestock and jeopardizes the lives of herders who depend on their animals for food, fuel, income, and transportation) that resulted in a loss of nearly six million of the country's 33 million livestock (1,2). As a result, severe psychological stress and increased school drop-out rates have been reported, and increased migration of rural herders into urban centers has placed a burden on water, sanitation, medical, and social services. This disaster threatened the health and food security of approximately 40% of the country's population (2). The Mongolian Ministry of Health asked the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) for assistance in assessing the nutritional effects of the 2000--2001 dzud on children aged 6--59 months. This report summarizes the results of that assessment, which indicated that affected districts had no excess nutritional wasting in any age group; however, excess growth stunting and anemia were common in both affected and unaffected districts. Expanded monitoring of this population is needed to determine the causes of malnutrition and to develop appropriate interventions. The Mongolian government classified districts as severely, moderately, slightly, or not affected by the 2000--2001 dzud based on reported livestock deaths in each district. In June 2001, 474 children aged 6--59 months were randomly selected from the 73 severely affected districts; a comparison group of 463 children of similar age were randomly selected from the 184 districts slightly or not affected (i.e., unaffected). A three-stage cluster sample design was used to identify districts, subdistricts, and children (selected from local civil and medical registration lists) for inclusion in the samples. The 45 districts designated as moderately affected and the capital city of Ulaan Bataar were not included in the survey. Informed verbal consent to participate was obtained from a parent or caretaker of each selected child. An adult household member was asked about livestock deaths since December 2000 and number of livestock that remained. Each child was assessed by anthropometry (height or length and weight), hemoglobin measurement, and a targeted physical examination. Height or length was measured to the nearest 1 mm using a standard height board, and weight was measured to the nearest 100 g using a digital bathroom scale (Figure 1). Wasting (low weight for height), stunting (low height for age) and underweight (low weight for age) were defined as a z-score >2.0 standard deviations below the median of the international National Center for Health Statistics/WHO reference population (3). In this reference population, 2.3% of children have a z-score below -2.0. Capillary blood was obtained by fingerstick from all selected children, their mothers, and a subsample of male household members aged 18--59 years and tested using Hemocue hemoglobinometers in the field. At an altitude of <1,000 m, anemia was defined as hemoglobin <11.0 g/dL for children, <12.0 g/dL for nonpregnant mothers (n=837), and <13.0 g/dL for men (n=176), with cut-offs for higher altitudes adjusted according to WHO recommendations (4). Children were excluded from analysis whose height or weight measurements were missing or whose z-scores were outside the plausible ranges suggested by WHO (n=35) (3) or whose hemoglobin values were missing (n=3). The final cohort consisted of 454 children in the dzud-affected sample and 445 children in the unaffected sample. Data were analyzed using EpiInfo version 6.04 and SUDAAN version 7.5. Mongolian livestock consists primarily of cows, horses, sheep, goats, and camels. Livestock losses were higher in the affected districts, in which the median proportion of all animals lost as reported by households was 32.1% (range: 0--100%); in unaffected districts, the median loss was 7.4% (range: 0--100%). No significant differences were found in the age and sex distributions of children and in the prevalence of wasting, stunting, or underweight between children in the affected and unaffected samples (Table 1). The prevalence of wasting in both samples was below the 2.3% level in the reference population. In contrast, approximately one third of children had evidence of growth stunting in both the affected and unaffected samples. Among children aged 6--23 months, the prevalence of stunting was higher in the affected districts than in the unaffected districts (p=0.07). The overall distributions of height-for-age scores were substantially lower in both samples than in the reference population (Figure 2). No differences were found between the affected and unaffected samples in the prevalence of anemia among children, mothers, or men. Approximately half of the children aged 6--23 months were anemic (46% [95% confidence interval (CI)= 38.0%-- 55.1%] and 52.5% [95% CI=43.7%--60.7%]) in the dzud-affected and unaffected districts, respectively. The prevalence of anemia was lower among children aged >2 years (16.2% [95% CI=10.3%--22.1%] and 12.6% [95% CI=12.6%--24.7%]) in affected and unaffected districts, respectively. Anemia was common among nonpregnant mothers (16.6% [95% CI=11.1%--22.1%] and 17.3% [95% CI=12.2%--22.5%]) and rare among men (2.3% [95% CI=0.2%--4.4%] and 2.5% [95% CI=0.3%--5.5%]) in affected and unaffected districts, respectively. Reported by: N Bolormaa, MD, B Byambatogtoch, MD, D Erjen, PhD, B Gerejargal, MSc, D Ganzorig, MD, Y Tserendolgor, PhD, National Nutrition Research Center of the Public Health Institute, Ministry of Health, Mongolia. Div of Applied Public Health Training, Epidemiology Program Office; Div of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; BA Woodruff, MD, Div of Emergency and Environmental Health Svcs, National Center for Environmental Health; MK Serdula, MD, L Kettel Khan, PhD, Div of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; RB Kaufmann, PhD, Office of Global Health, National Center for Environmental Health; J Bates, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate a high prevalence of growth stunting, which is indicative of chronic malnutrition, but no evidence of excess wasting, which is indicative of acute malnutrition. The prevalence of stunting among younger children might have been somewhat greater in affected than in unaffected districts because children aged <24 months grow more rapidly than older children; therefore, growth faltering associated with a nutritional deficit might be noticeable earlier. The prevalence of anemia in both samples was high among the youngest children, moderate among nonpregnant women, and very low among men, suggesting iron deficiency associated with poor iron intake as the underlying cause of anemia (5). Approximately half of the children aged 6--23 months in both the affected and unaffected samples had anemia; this level indicates the need for universal iron supplementation in this age group (6). Mutton and other red meats are sources of highly bioavailable iron and are among the staples of the Mongolian diet, but quantity of consumption among the youngest children might be insufficient to meet iron requirements. This assessment might have underestimated the nutritional effects of the 2000--2001 dzud on children for at least five reasons. First, the classification of dzud severity status was developed by the Mongolian government to assess the economic impact of the dzud and may have been too imprecise to allow detection of differences in health status. Second, relief efforts to distribute food to affected areas might have lessened the nutritional impact of livestock losses among herders and their families. Third, only the 2000--2001 dzud was assessed; families affected by both dzuds could be at greater risk than families affected by only one. Fourth, because herders store food in the fall for the following winter and spring, the effects of the 2000--2001 dzud might not have been felt immediately. A family that had adequate food stocks for this past winter and spring might be unable to replace food stocks for the following winter. Finally, as a result of the dzud disaster, thousands of herders who lost all or nearly all their animals migrated to urban centers in search of work and food. The children of these herders might be at extreme nutritional risk but would not have been represented if they were not yet registered with local civil or medical authorities at the time of the survey or if they had relocated to Ulaan Bataar. Additional assessment and interventions are needed to improve nutritional deficiencies among children in Mongolia. Recommendations include the nutritional assessment of the recent migrant population not represented in this survey and additional support for growth promotion programs already being developed, especially among the youngest children in severely dzud-affected districts, for early identification, and intervention for children who show growth faltering. Additional strategies include universal supplementation of iron among children aged <2 years and more broad-based population interventions to fortify staple foods with iron. References

Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 1/10/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 1/10/2002

|