|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

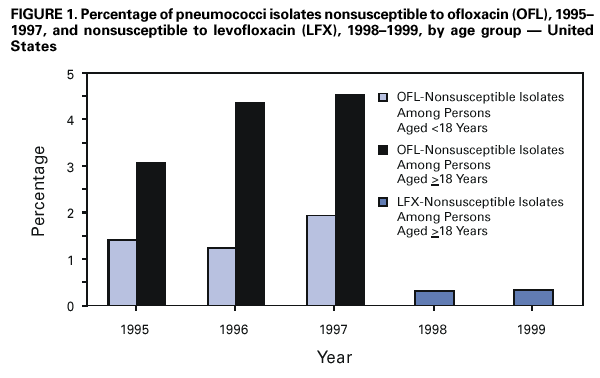

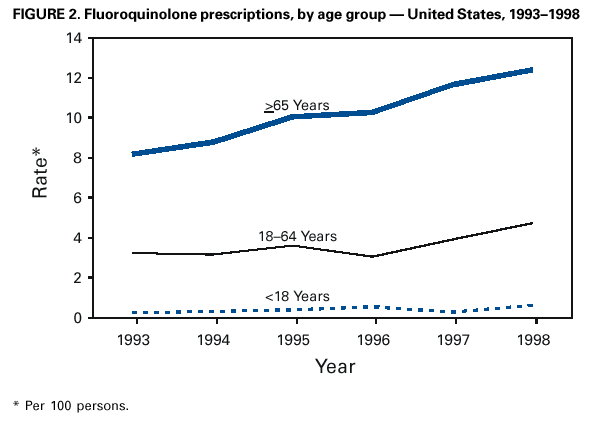

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to Fluoroquinolones ---United States, 1995--1999Streptococcus pneumoniae is the leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, and otitis media in the United States. Because of the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in pneumococci, fluoroquinolones are now recommended by some groups for the treatment of pneumonia in adults, especially when antimicrobial resistance is suspected (1--3). Older fluoroquinolones with some antimicrobial activity against the pneumococcus include ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin. Newer fluoroquinolones with higher in vitro activity against the pneumococcus, including levofloxacin, grepafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin, are available in the United States. Fluoroquinolone resistance to the pneumococcus is rare (4,5) but may be increasing in Canada (6). To determine trends of pneumococcal resistance to fluoroquinolones in the United States, invasive pneumococcal disease surveillance data were analyzed from Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) during 1995--1999. Fluoroquinolone prescription data were obtained from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) during 1993--1998. This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicate that pneumococci with reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones are appearing in the United States. Appropriate use of antibiotics and continuous prospective surveillance for antimicrobial resistance are necessary to slow the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant pneumococci. ABCs is an ongoing, active, population-based surveillance system for invasive pneumococcal disease conducted in selected areas of the United States. This analysis includes ABCs areas with continuous surveillance during 1995--1999. These areas include selected counties in California, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, Oregon, and Tennessee (aggregate population: 17.3 million). A case of invasive pneumococcal disease was defined as isolation of pneumococcus from blood or other normally sterile site from a resident of one of the surveillance areas. Isolates were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility to ofloxacin (1995--1997) or levofloxacin and trovafloxacin (1998--1999) using the broth microdilution method, as recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (7). Definitions for interpretation of susceptible, intermediate, and resistant isolates also were from NCCLS (8); isolates that were either intermediate or resistant were considered nonsusceptible. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates. All pneumococci isolated in 1998 and 1999 were serotyped using the quellung reaction. NHAMCS collects data on the use and provision of ambulatory care services in hospital emergency and outpatient departments on a representative national sample. U.S. Bureau of the Census data were used to determine population denominators for fluoroquinolone use. The chi-square test for comparison of proportions and chi-square for linear trends were used for analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. During 1995--1997, susceptibility testing was performed on 8763 isolates from persons with pneumococcal invasive disease, representing 81.5% of cases identified through ABCs. During 1998--1999, susceptibility testing was available for 6529 cases of pneumococcal invasive disease, representing 84.9% of all identified cases. Overall, the prevalence of ofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC]: >4 µg/mL) increased from 2.6% (65 of 2508) in 1995 to 3.8% (119 of 3108) in 1997 (chi-square for linear trend=5.24; p=0.02). Levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates (MIC: >4 µg/mL) were 0.2% of isolates in 1998 (seven of 3120) and in 1999 (eight of 3432) (Figure 1). Of 15 levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates, 13 also were nonsusceptible to trovafloxacin. Isolates that were not susceptible to ofloxacin were more common among persons aged >18 years (225 [3.6%] of 6317) than among persons aged <18 years (64 [2.6%] of 2446) (p=0.02). Among adults, the prevalence of ofloxacin-nonsusceptible pneumococcal isolates increased from 3.1% (55 of 1791) in 1995 to 4.5% (103 of 2276) in 1997 (chi-square for linear trend=5.33; p=0.02). The proportion of ofloxacin-resistant isolates (MIC: >8 µg/mL) did not increase significantly (0.3% in 1995, 0.2% in 1996, and 0.4% in 1997). Of the 225 ofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates from adults, 62.2% were from whites and 51.6% were from males. These proportions were similar for ofloxacin-susceptible isolates (57.7% from whites and 52.9% from males). Ofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates were from patients residing in six of the seven surveillance areas. All levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates were from adults (median age: 77 years; range: 44--89 years). Among adults, 0.2% (seven of 2340) of pneumococci were nonsusceptible (MIC: >4 µg/mL) to levofloxacin in 1998 and 0.3% (eight of 2451) in 1999. Of the 15 levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates, one was intermediately resistant. Fourteen (93.3%) of the levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates were from whites, and nine (60%) were from males. The proportion of levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates was significantly higher among isolates from persons aged >65 years (p<0.001) and among whites (p<0.001), as compared with levofloxacin-susceptible isolates. Ten serotypes were identified among the 15 levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates: 6A, 6B, 9V, 14, 16, 18C, 19F, 22F, 23F, and 35B. Eight of the 15 isolates were obtained from residents residing in one surveillance area (Connecticut). In this area, 0.9% of invasive pneumococcal isolates were nonsusceptible to levofloxacin, compared with 0.2% for all other areas. Examination of the isolates from Connecticut using PFGE showed eight unrelated patterns. Fluoroquinolone resistance was associated with resistance to other antimicrobials. Among the 225 isolates that were nonsusceptible to ofloxacin, 44 (19.6%) also were nonsusceptible to penicillin (MIC: >0.12 µg/mL), 23 (10.2%) to cefotaxime (MIC: >1 µg/mL), 20 (8.9%) to erythromycin (MIC: >0.5 µg/mL), and 68 (30.2%) to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (MIC: >1/19 µg/mL). Among the 15 isolates nonsusceptible to levofloxacin, nine (60%) had decreased susceptibility to penicillin, eight (53.3%) were nonsusceptible to cefotaxime, five (33.3%) to erythromycin, and nine (60%) to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. In comparison, among the 4623 levofloxacin-susceptible isolates, 1018 (22%) were nonsusceptible to penicillin, 594 (12.8%) were nonsusceptible to cefotaxime, 650 (14%) to erythromycin, and 1229 (26.6%) to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. During 1993--1998, fluoroquinolone prescriptions in the United States increased from 3.1 to 4.6 per 100 persons per year. The frequency of fluoroquinolone prescriptions was highest among persons aged >65 years and increased in this age group from 8.2 to 12.4 per 100 persons per year (Figure 2). Prescriptions written in the United States for all antibiotics decreased from 53.5 to 51.5 per 100 persons per year for all ages during this period. Reported by: P Daily, MPH, L Gelling, MPH, G Rothrock, MPH, A Reingold, MD, California Emerging Infections Program, San Francisco; D Vugia, MD, Acting State Epidemiologist, California Dept of Health Svcs. NL Barrett, MS, J Hadler, MD, State Epidemiologist, Connecticut Dept of Public Health. W Baughman, MSPH, M Farley, MD, Veterans Administration Medical Center and Emory Univ School of Medicine, Atlanta; PA Blake, MD, State Epidemiologist, Georgia Dept of Health. MA Pass, J Roche, MD, LH Harrison, MD, Johns Hopkins Univ, Baltimore; J Roche, MD, Acting State Epidemiologist, Maryland State Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene. SK Johnson, MT, CA Lexau, MPH, R Lynfield, MD, R Danila, MD, Assistant State Epidemiologist, Minnesota Dept of Health. K Stefonek, MPH, PR Cieslak, MD, MA Kohn, MD, State Epidemiologist, Oregon Health Div. B Barnes, W Schaffner, A Craig, MD, State Epidemiologist, Tennessee Dept of Health. JH Jorgensen, PhD, L McElmeel, S Crawford, Univ of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio, Texas. Respiratory Diseases Br, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases and Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network, National Center for Infectious Diseases; and an EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that fluoroquinolone-nonsusceptible pneumococci are present in the United States; however, it is unclear whether resistance is increasing with the newer fluoroquinolones. The proportion of isolates that were ofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates increased during 1995--1997. The main mechanisms of resistance to fluoroquinolone agents are alterations on DNA gyrase subunits and reduced penetration associated with decreased outer membrane protein production. These mechanisms are common between ofloxacin and the newer fluoroquinolone agents, although ofloxacin-resistant strains may be seen with a single mutation to DNA gyrase and newer fluoroquinolones and require mutations in both mechanisms for resistance (9,10). Therefore, trends in ofloxacin susceptibility may predict what will occur for other fluoroquinolone agents. The growing use of fluoroquinolones probably contributes to the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant pneumococci. Fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates were more common among persons aged >65 years, who have the highest density of fluoroquinolone use. In comparison, penicillin-resistant strains are more common among isolates from young children, who have the highest rate of beta-lactam use. Fluoroquinolones are not licensed for use in children, a factor that may be helping to slow the rate of emerging fluoroquinolone resistance. PFGE results suggest that the emergence of resistant isolates does not result from spread of a single resistant clone. Levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates had reduced susceptibility to other antimicrobials used for the treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia, notably penicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, erythromycin, and cefotaxime. Most levofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates also were nonsusceptible to trovafloxacin. These findings have important implications given that fluoroquinolones are recommended for the treatment of pneumococcal infections when penicillin resistance or resistance to other antimicrobials is suspected. Few therapeutic options exist for invasive disease attributable to pneumococci resistant to quinolones and other agents. Susceptibility testing for ofloxacin and levofloxacin at ABCs started in 1995 and 1998, respectively. Therefore, results presented in this report are limited by the short time that systematic testing for levofloxacin susceptibility has been available and by the lack of continuity for testing of a single fluoroquinolone agent during this period. Identification of decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones in ABCs sites is population based and representative of the areas under surveillance. ABCs does not provide comprehensive national surveillance, but provides a good approximation of national trends. Fluoroquinolones are important agents for treating pneumococcal infections and community-acquired pneumonia. Appropriate use of antibiotics is crucial for slowing the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance. Principles for appropriate use of antibiotics in adults are available at <http://www.cdc.gov/antibioticresistance/technical.htm>. Continuous prospective surveillance for antimicrobial resistance in pneumococci is needed to determine whether increases in fluoroquinolone resistance will occur in the United States. If fluoroquinolone resistance becomes more common, clinical laboratories should consider routine susceptibility testing of fluoroquinolones on invasive pneumococcal isolates. Several state health departments have established surveillance for cases of invasive drug-resistant S. pneumoniae. Because fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates have been rare, clinicians and microbiology personnel are encouraged to report episodes of suspected fluoroquinolone resistance in pneumococcal isolates collected from blood or cerebrospinal fluid to their state or local health department. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/21/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/21/2001

|