|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

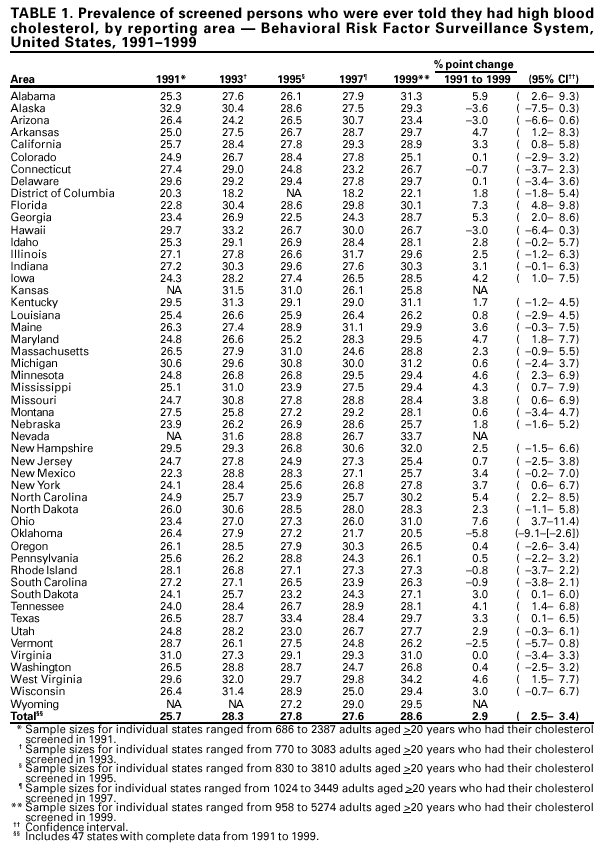

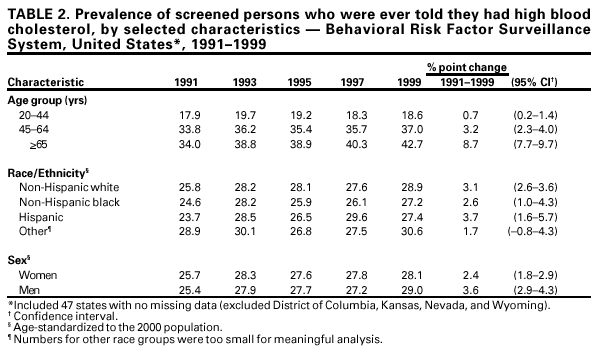

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. State-Specific Trends in High Blood Cholesterol Awareness Among Persons Screened --- United States, 1991--1999High blood cholesterol (HBC) is a major risk factor for heart disease. One of the national health objectives for 2010 is to reduce the percentage of adults aged >20 years with total blood cholesterol levels of >240 mg/dL (objective 12--14) (1). One strategy for achieving this objective is to increase awareness of HBC. State-specific data allow state health departments to monitor progress in educating the public about awareness of cholesterol levels and the need for persons to maintain low levels of blood cholesterol. To examine state-specific trends in the proportion of screened adults who reported that they were told that they had HBC, CDC analyzed data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for 1991 through 1999. This report summarizes the results of that analysis and indicates that approximately one fourth of screened survey participants were aware that they had HBC; this proportion increased slightly from 1991 through 1999. Awareness of HBC is a necessary step to help persons take action to lower their cholesterol level and their risk for coronary heart disease. BRFSS is a random-digit--dialed telephone survey of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population aged >18 years. For this report, BRFSS data from 1991, 1993, 1995, 1997, and 1999 were analyzed for 412,322 persons aged >20 years from 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC). Survey participants were asked whether they had ever had their blood cholesterol checked and, if so, had a physician or other health-care provider ever told them their blood cholesterol was high. Those who reported having ever had their blood cholesterol checked were included in the analysis and those who reported they had been told they had HBC were classified as being aware they had HBC (n=120,450). Data were weighted to account for the age, race/ethnicity, and sex distribution and nonresponse in each state. Analyses were conducted using SUDAAN 7.0 to account for the complex sampling design and to obtain accurate variance estimates. To allow for comparisons between states, the results were age-standardized with the direct method using the U.S. 2000 standard population (2). Participation rates in BRFSS ranged from 71.4% in 1993 to 55.2% in 1999. The prevalence of cholesterol screening during the preceding 5 years increased from 67.3% in 1991 to 70.8% in 1999 (3). Among all 50 states and DC that participated in BRFSS during 1999, the age-standardized prevalence of persons screened who were ever told that they had HBC ranged from 20.5% in Oklahoma to 33.7% in Nevada (Table 1). For the 47 states that participated in BRFSS in all years from 1991 through 1999, the age-standardized prevalence of HBC awareness among persons screened increased from 25.7% in 1991 to 28.6% in 1999 (Table 1). The age-standardized prevalence of HBC awareness among persons screened increased in DC and 38 states and ranged from a 0.1 percentage point increase in Delaware to a 7.3 percentage point increase in Florida. The increase in HBC awareness was significant in Alabama, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. For eight states (Alaska, Arizona, Connecticut, Hawaii, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Vermont), the prevalence of persons screened who reported HBC decreased from 1991 to 1999 and ranged from a 5.8 percentage point decline in Oklahoma to a 0.7 percentage point decline in Connecticut. The decrease was significant in Oklahoma. In Virginia, the prevalence of reported HBC among persons who ever had their cholesterol tested remained constant at 31.0% during 1991--1999. From 1991 to 1999, HBC awareness increased among all demographic groups (Table 2). The percentage of persons who had ever had their cholesterol tested and who reported having been told that they had HBC was consistently higher for successive age groups (from 18.6% among those aged 20--44 years to 42.7% among those aged >65 years for 1999). Reported HBC awareness was higher in 1999 than in 1991 among non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics. Numbers for American Indians/Alaska Natives and Asians/Pacific Islanders were too low for meaningful analysis. Awareness of HBC was higher among women than men until 1999 and increased for both men and women. Reported by the following BRFSS coordinators: S Reese, Alabama; P Owens, Alaska; R Weyant, Arizona; B Woodson, Arkansas; B David, California; D Brand, Colorado; M Adams, Connecticut; F Breukelman, Delaware; I Bullow, District of Columbia; S Oba, Florida; L Martin, Georgia; F Reyes-Salvail, Hawaii; J Aydelotte, Idaho; B Steiner, Illinois; L Stemnock, Indiana; J Igbokwe, Iowa; C Hunt, Kansas; T Sparks, Kentucky; B Bates, Louisiana; J Graber, Maine; H Lopez, Maryland; D Brooks, Massachusetts; H McGee, Michigan; N Salem, Minnesota; D Johnson, Mississippi; J Jackson-Thompson, Missouri; P Feigley, Montana; L Andelt, Nebraska; E DeJan, Nevada; J Porter, New Hampshire; G Boeselager, New Jersey; W Honey, New Mexico; C Baker, New York; Z Gizlice, North Carolina; L Shireley, North Dakota; P Pullen Cross, Ohio; K Baker, Oklahoma; K Pickle, Oregon; L Mann, Pennsylvania; J Hesser, Rhode Island; M Wu, South Carolina; M Gildemaster, South Dakota; D Ridings, Tennessee; K Condon, Texas; K Marti, Utah; C Roe, Vermont; J Hicks, Virginia; KW Simmons, Washington; F King, West Virginia; K Pearson, Wisconsin; M Futa, Wyoming. LM Henderson, Univ of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Cardiovascular Health Br, Div of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that among persons who had their cholesterol level screened, the percentage who were told by a health-care provider that they had HBC increased significantly from 1991 to 1999. BRFSS data on cholesterol screening trends indicated an increase in the proportion of U.S. adults aged >20 years who were screened during the preceding 5 years for HBC from 67.3% in 1991 to 70.8% in 1999 (3). Possible reasons for this increase include improved efforts by public health programs to increase awareness of cholesterol levels, increased counseling by health-care providers, or an increase in HBC prevalence. However, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest that cholesterol levels are declining (4). No national data allow state-level estimates of HBC based on actual blood cholesterol measurements. NHANES used directly measured cholesterol and observed decreasing cholesterol levels among adults between the 1971--1974 and 1988--1994 surveys (4). More recent data from NHANES are not available. The differences in reported HBC across demographic variables (age, sex, and race/ethnicity) in BRFSS are consistent with those measured in NHANES III (4). The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, BRFSS data are self-reported, and some respondents may have over or underestimated their HBC status. Patients may not have been told that they had high cholesterol and may have underestimated their HBC status. However, the actual cut-point used by health-care providers is unknown, and patients with borderline high cholesterol may have been told that their cholesterol was high, which might have resulted in an overestimate of true prevalence. Second, because BRFSS is a telephone-based survey, and persons with lower socioeconomic status are less likely than more affluent persons to have a telephone, persons with lower socioeconomic status may be underrepresented. Control of HBC requires successful implementation of multiple steps among both patients and health-care providers, including ongoing screening for HBC, knowing one's cholesterol levels, and treating and managing HBC through lifestyle changes (e.g., reduced dietary intake of saturated fat and cholesterol, increased dietary intake of viscous fiber, increased exercise, and weight control) and medical treatment as appropriate. The National Cholesterol Education Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends that all persons aged >20 years have their cholesterol checked at least once every 5 years (5). In May 2001, NCEP released the third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) Report, which includes updated clinical guidelines for cholesterol testing and management (6,7). The new features of ATP III focus on primary prevention among those with multiple risk factors, including an assessment of the 10-year risk for a heart attack, modifications in lipid and lipoprotein classification levels, and implementation of the treatment recommendations. HBC is a modifiable risk factor for heart disease. The benefits of cholesterol lowering include a decrease in the incidence of coronary heart disease and a decline in mortality among those with or without coronary heart disease (8--10). HBC can be prevented or controlled with increased physical activity, adoption of diets low in saturated fats and cholesterol and high in fruits and vegetables, and with the use of drugs that lower cholesterol. References*

*All MMWR references are available on the Internet at <http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr>. Use the search function to find specific articles. Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/7/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/7/2001

|