|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

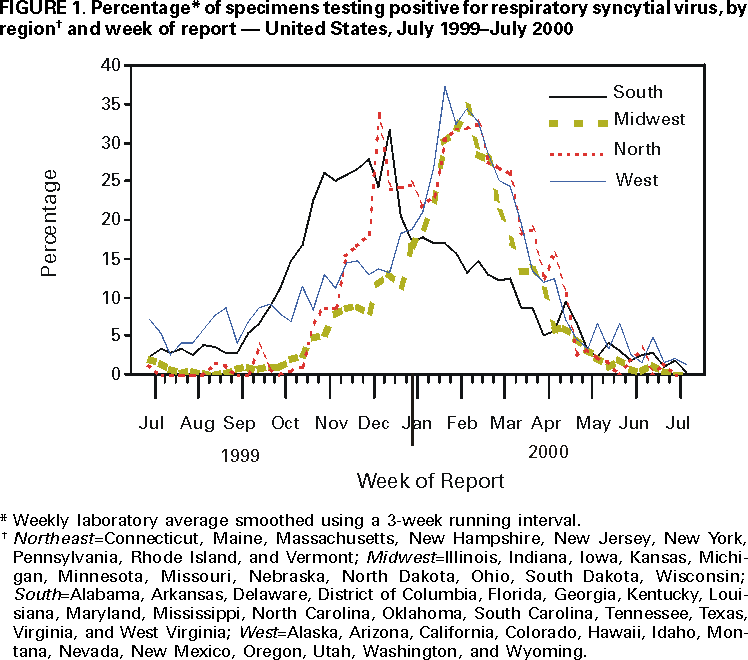

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Activity --- United States, 1999--2000 SeasonRespiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI) among infants and children worldwide (1) and is an important cause of LRTI among older children and adults (2). Despite the presence of maternal antibodies, most hospitalizations occur among infants aged <6 months, and nearly all children are infected by age 2 years (3). Although primary infection is usually most severe, reinfection throughout life is common (4). In temperate climates, RSV infections occur primarily during annual outbreaks, which peak during winter months (5). In the United States, RSV activity is monitored by the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS), a voluntary, laboratory--based system. This report summarizes trends in RSV activity reported to NREVSS from July 1999 through June 2000 and presents preliminary surveillance data from July 8 through November 21, 2000, which indicate that RSV community outbreaks are becoming widespread. Clinical and public health laboratories report weekly to CDC the number of specimens tested for RSV by antigen--detection or virus--isolation methods and the number of positive results. RSV activity is considered widespread by NREVSS when 1) >50% of participating laboratories report one or more RSV detections for at least 2 consecutive weeks, and 2) >10% of all specimens tested for RSV during a surveillance week are positive. Of the laboratories reporting data for the week ending November 4, 2000, 32 (53%) detected >10% of specimens positive for RSV for at least 2 consecutive weeks, indicating the onset of widespread RSV activity for the 2000--01 season. From July 1999 through June 2000, 72 laboratories in 45 states reported 123,769 tests for RSV; 18,981 (15%) were positive for RSV (Figure 1). In the United States, widespread RSV activity began during the week of October 30, 1999, and continued for 26 weeks, until the week of March 25, 2000. The timing of the onsets and conclusions of RSV regional outbreaks varied by state: range at onset was September 18 to January 29 and range at conclusions was January 29 to May 6. Regional RSV outbreaks occurred earliest in the South (23 sites; median weeks of onset and conclusion: October 16 and March 11, respectively), later in the Northeast (10 sites; November 27 and April 15), and latest in the Midwest (11 sites; December 28 and April 1) and West (12 sites; November 13 and April 8).* Although 92% of positive tests were reported for the week ending October 30 through the week ending March 25, RSV was detected throughout the year. For example, during July--August 1999, sporadic RSV isolates were reported from laboratories in California, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. For the July 1999--June 2000 surveillance period, the number of specimens that tested positive for RSV, average months of peak activity, and regional trends were similar to trends observed during previous years. The duration of the 1999--2000 RSV season also was consistent with that of previous years, including the typical earlier onset of RSV outbreaks reported by southern laboratories. Reported by: National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System collaborating laboratories. Respiratory and Enteric Viruses Br, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial Note:Severe manifestations of RSV infection (e.g., pneumonia and bronchiolitis) most commonly occur among infants aged 2--6 months, and hospitalization rates for these diagnoses have been used as an indicator for severe RSV disease among young children. In the United States, bronchiolitis hospitalization rates among children aged <1 year were 31.2 per 1000 in 1996 (6) and were 61.8 per 1000 children aged <1 year among American Indian/Alaska Native children receiving care through the Indian Health Service (7). NREVSS consists of 84 widely distributed laboratories and permits characterization of geographic and temporal trends of RSV infections in the United States. NREVSS data can alert public health officials and physicians to the timing of seasonal RSV activity. Although no RSV vaccine is available, RSV immune globulin intravenous and a humanized murine anti--RSV monoclonal antibody are recommended as prophylaxis for some highrisk infants and young children (e.g., those born prematurely or with chronic lung disease) to prevent serious RSV disease (8). Nosocomial transmission of RSV can be controlled by using contact isolation procedures. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, laboratory data serve as an indicator of when RSV is circulating in a community; however, the correlation of these data to disease burden in the population is uncertain. Second, some regions are represented by few laboratories. Finally, results may not be confirmed in some laboratories. Symptomatic RSV disease can recur throughout life because of limited protective immunity induced by natural infection. As a result, healthcare providers should consider RSV as a cause of acute respiratory disease in children and adults during community outbreaks. Persons with underlying cardiac or pulmonary disease or compromised immune systems and the elderly are at increased risk for serious complications of RSV infection, such as pneumonia and death (9). RSV infection among recipients of bone marrow transplants has resulted in high mortality rates (83%) (10). Additional information and updated data on RSV trends are available on the CDC WorldWide Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/nrevss. References

* Northeast=Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Midwest=Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin; South=Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; West=Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 12/7/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|