|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

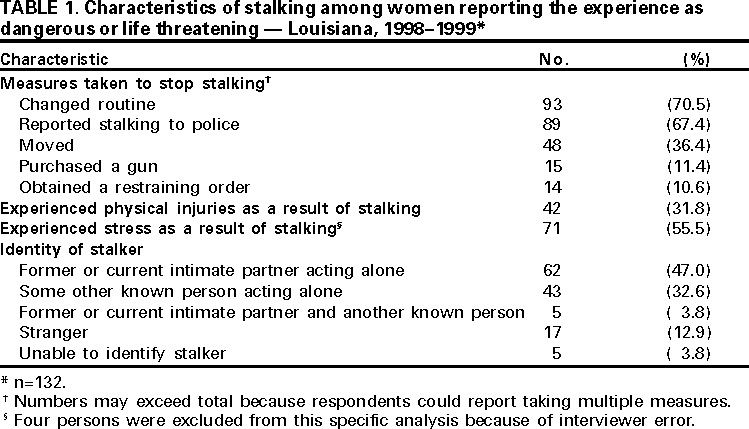

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Prevalence and Health Consequences of Stalking --- Louisiana, 1998--1999Stalking is a form of violence that may lead to physical injury or homicide and may have disabling social and psychological consequences (1,2). Although the legal definition varies among jurisdictions, all 50 states have antistalking laws (3). Louisiana defines stalking as the willful, malicious, and repeated following or harassing of another person with the intent to place that person in fear of death or serious bodily injury (4). Information is limited on the prevalence of stalking and its impact on the victim (3,5). To gather population-based surveillance data on stalking and other forms of interpersonal violence, the Louisiana Office of Public Health conducted a random-digit--dialed telephone survey among residents regarding experiences and perceptions related to safety and violence. This report summarizes the results of the survey, which indicate that 15% of the women surveyed reported being stalked during their lifetime. Data were collected from Louisiana residents aged >18 years on a monthly basis from July 1, 1998, to June 30, 1999. Eligible households were selected randomly from a list of possible telephone numbers that had been filtered to eliminate unused and business exchanges. The respondent interviewed from each household was selected randomly. If an eligible household refused to participate or if the desired respondent could not be reached, a substitute number was selected randomly from the list. The survey ensured confidentiality, and respondents gave informed consent for participation. Of 4763 eligible respondents, 1808 (38%) completed the interview; 1171 (65%) were women. This report describes the findings among women respondents. Age and race of survey participants matched the 1990 census data for Louisiana, except that women aged 18--24 years composed 8% of the survey sample and composed 14% of women in Louisiana. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 99 years (median: 46 years); 71% were white, and 28% were black, whereas among female Louisiana residents aged >18 years, 69% were white, and 29% were black. Participants were classified as having ever been stalked if they answered "yes" to the question, "Have you ever been stalked, harassed, or threatened with violence for more than one month by someone who would not leave you alone?" Women who reported having been stalked also were asked whether they had experienced physical injuries and stress-related problems and the level of fear invoked by stalking. One hundred seventy-six (15%) women reported having been stalked during their lifetime, and 23 (2%) women reported currently being stalked. Of the 176, 132 (75%) women reported they believed the stalking to be somewhat dangerous or life threatening; of these, 89 (67%) indicated they had reported the situation to the police. Other measures reported to stop harassment included changing usual behavior (70%), moving (36%), purchasing a gun (11%), and obtaining a restraining order (11%) (Table 1). Forty-two (32%) of the 132 women reported injuries from being assaulted by their stalker, such as swelling, cuts, scratches, bruises, strains or sprains, burns, bites, broken teeth, or knife or gunshot wounds. Seventy-one (55%) women reported experiencing stress that interfered with their regular activities for >1 month. Among the women who perceived their stalking to be dangerous or life threatening, 67 (51%) identified the perpetrators as someone with whom they had had an intimate relationship (i.e., boyfriend, former boyfriend, spouse, or former spouse); no stalking was reported among same sex partners. Forty-three (33%) women identified the perpetrator as someone known to them but other than an intimate partner (i.e., relative, acquaintance, friend, or other). Seventeen (13%) women were stalked by a stranger, and five (4%) were stalked by a perpetrator that they were unable to identify. Those women who had been in an intimate relationship with their stalker were more than four times as likely to report that they had sustained an injury than those women who had not been in an intimate relationship with their stalker (35 of 67 versus seven of 60; relative risk=4.5; 95% confidence interval=2.2--9.3). None of the women who reported having been stalked by a stranger and who believed the stalking was somewhat dangerous or life threatening reported sustaining an injury. Reported by: M Kohn, MD, State Epidemiologist, Oregon Health Div. H Flood, MPH, J Chase, MSPH, PM McMahon, PhD, Injury Research and Prevention Section, Louisiana Office of Public Health. Family and Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Team, Div of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that 15% of women surveyed in Louisiana reported having been stalked during their lifetime. Social and psychological sequelae of stalking were more prevalent than physical sequelae. More women reported experiencing stress from being stalked than experiencing physical injury. The findings in this report are consistent with data from the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS) (3); both surveys showed that stalking had adverse psychological and social consequences. NVAWS did not measure physical injuries resulting from stalking because their definition of stalking precluded physical contact; however, NVAWS separately measured physical violence and found that 81% of those reporting stalking also reported having been physically assaulted by the same person (4). The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, quantifying the validity of self-reports of stalking is difficult because no "gold standard" exists for comparison. Additional research is needed on experiences of violence to determine the validity and reliability of different data collection methods (e.g., face-to-face interviews, telephone surveys, and paper and pencil surveys). Second, the population surveyed may not be representative of Louisiana. Because persons without telephones were not surveyed, and because of the low response rate, nonparticipants may differ from participants on study outcomes. However, the racial composition of survey participants was representative of the state. The data in this report suggest that reliable estimates of stalking may be difficult to obtain using traditional data sources (e.g., health-care providers and law enforcement agencies) because 68% of the women who experienced stalking did not sustain a physical injury and 33% did not report the stalking to the police. A population-based survey may help characterize the burden of stalking and other types of interpersonal violence. However, the identification of victims in health-care and law enforcement settings also may help characterize persons at high risk for injury from stalking and enable referral of those persons for services and secondary prevention activities. Surveillance is the basis for the epidemiologic approach to public health problems (6). If violence prevention is to be approached using the public health model, an accurate description of the problem is the first step (7). State- and local-level data on the prevalence of interpersonal violence can assist health departments in tailoring intervention programs to the specific needs and conditions in their communities. References

Table 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 7/27/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|