|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

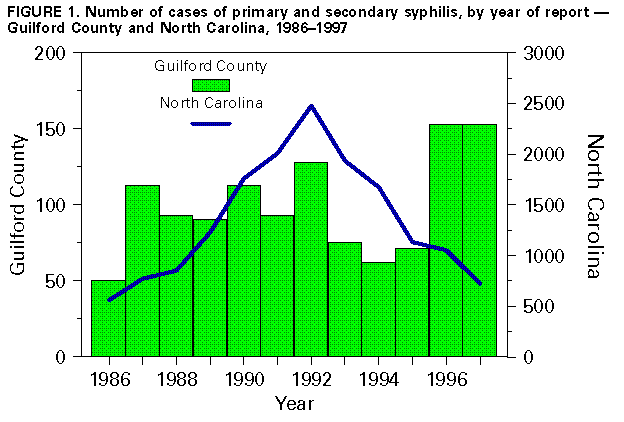

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Outbreak of Primary and Secondary Syphilis -- Guilford County, North Carolina, 1996-1997In 1996 and 1997, 153 cases of primary and secondary (P&S) syphilis were reported each year in Guilford County, North Carolina, a 147% increase from the 62 cases reported in 1994 (Figure_1). The incidence of P&S syphilis in Guilford County during 1996-1997 was 40.5 cases per 100,000 persons, substantially higher than the national health objective for 2000 of four cases per 100,000 (objective 19.3) (1). In comparison, the number of P&S syphilis cases in North Carolina declined 57% from 1994 to 1997 (Figure_1), to a rate of 10.9 per 100,000 in 1997. This report summarizes the results of an investigation conducted by the Guilford County Health Department (GCHD), the North Carolina Division of Epidemiology, and CDC, which suggest this ongoing outbreak has been associated with missed opportunities for syphilis screening and treatment in high-risk settings, increased exchange of sex for money or drugs, and substantial rates of coinfection with syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among those tested. To assess factors associated with the epidemic, interviews were conducted with P&S syphilis patients, state and local health department staff members, clinicians, and community residents. Demographic data for all residents of Guilford County with reported cases of syphilis from January 1993 (when the present data registry system was initiated) through August 1997 were analyzed to assess trends in factors that might influence syphilis rates (e.g., access to medical care and adequacy of screening and treatment). Also reviewed were the contact index (the number of sex partners for whom information was sufficient to initiate efforts to locate the person divided by the number of persons with syphilis interviewed) and the treatment index (the number of persons treated as a result of partner notification divided by the number of persons interviewed). The roles of illicit-drug use and sex worker activity during the epidemic were assessed. HIV screening and prevalence data were used to assess the extent of HIV coinfection among P&S syphilis patients. Syphilis registry data were used to compare risk factors among P&S syphilis patients reported during the pre-epidemic period (January 1993-December 1995) with P&S syphilis patients reported during the epidemic period (January 1996-August 1997). Screening and prevalence data from the local jails were reviewed (2-6). Seventy-three percent of Guilford County residents reside in two major cities: Greensboro (1990 population: 192,000) and High Point (1990 population: 74,000). Most (96%) reported P&S syphilis patients in Guilford County reside in these two cities. Of patients in Guilford County who had infectious syphilis from January 1996 through August 1997, 55% were men. The mean age of men with P&S syphilis was 34.5 years in 1993 and 37.2 years during January-August 1997 (p=0.2). The mean age of women with P&S syphilis increased significantly from 1993 (27.8 years) through August 1997 (33.3 years) (p=0.01). Patients during the epidemic period were more likely to have used illicit drugs at some time since 1978 (odds ratio {OR}=1.9; 95% confidence interval {CI}=1.1-3.3) and to have exchanged sex for drugs or money during the preceding year (OR=2.1; 95% CI=1.4-3.3) and were less likely to have been tested for HIV (18.6%) than patients before the epidemic period (27.8%; OR=0.6; 95% CI=0.4-0.9). Of P&S syphilis patients tested for HIV infection before and during the epidemic, 16% and 13%, respectively, were HIV infected. On the basis of local police records, prostitution arrests did not increase during 1993-1996, but crack cocaine-related arrests increased 69%. Public sexually transmitted diseases clinical care appeared to meet the needs of persons seeking care during the epidemic in Greensboro. The contact index was 2.0 in 1993 and 1.7 in 1996, indicating fewer sex partners named per patient interviewed in 1996. However, the treatment index was 0.9 in 1993 and 1.0 in 1996, indicating more patients and contacts were treated for syphilis or preventively treated in 1996. At the Guilford County jail, full health assessments were offered after 10-14 days of detainment. However, because of a rapid turnover and a high refusal rate, most detainees were not screened. In 1996, 9.6% of those detained in the jail system were screened for syphilis and less than 1% were screened for HIV infection; 7.5% of syphilis tests and 3.3% of HIV tests were positive. During January-August 1997, 8.0% of detained inmates had a history, physical examination, and syphilis serology, of whom 13.3% had reactive syphilis serologic tests. To control the increase in syphilis cases in Guilford County, the North Carolina HIV/STD Prevention and Care Section and GCHD, in collaboration with local community organizations, conducted a community intervention effort from July through September 1997. This intervention combined sex partner notification strategies, community outreach, and extended local clinical services to find and treat more patients with P&S syphilis and to educate the community about syphilis. Other prevention measures included alerting the local medical community; obtaining help from community-based organizations in identifying locations where at-risk persons are commonly found and increasing education, outreach, and screening at these locations; and increasing screening and treatment for syphilis at local settings where persons at high risk may have been encountered (e.g., jails). Based on reported cases of P&S syphilis in Guilford County through August 1998, P&S syphilis is expected to decrease 38% in 1998 compared with 1997. Reported by: H Gabel, MD, Guilford County Health Dept, Greensboro; E Foust, MPH, D Ogburn, N Engel, J Owen-O'Dowd, A Howerton-Privott, North Carolina HIV/STD Prevention and Care Section, North Carolina Dept of Health and Human Svcs; Greensboro Police Dept. Div of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: This investigation identified epidemiologic factors frequently associated with syphilis outbreaks in other urban areas of the United States: increased illicit-drug use and exchange of money or drugs for sex. This investigation also identified missed opportunities for rapid syphilis screening and treatment at the local jails. Previous studies have identified emergency departments (EDs) and jails as sites of high syphilis prevalence during epidemics (2-6). Many arrested persons lack medical insurance or have used hospital EDs at their last medical visit (2). Therefore, jails and EDs are potentially high-impact settings for rapid screening and treatment of patients at high risk for syphilis in areas with endemic or epidemic syphilis (2-6). Increased cocaine arrests corroborated community perceptions of increased crack cocaine use in Guilford County before the onset of the P&S syphilis epidemic. Also, data on P&S syphilis patients during 1996-1997 document increased exchange of sex for drugs or money and an increase in injecting or other drug use, compared with patients during 1993-1995. The link between crack cocaine and injecting-drug use and high-risk sex behaviors has been reported previously (7). The sequelae of syphilis are substantial, including facilitation of HIV transmission, congenital syphilis, and advanced syphilis lesions affecting the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. The high frequency of HIV infection among persons tested who also have P&S syphilis underscores the need to make HIV counseling, testing, and prevention a priority for patients with syphilis. Syphilis elimination is a feasible goal in the United States as syphilis rates continue to decline nationally, but outbreaks of P&S syphilis and persisting endemic foci are major obstacles (8). Outbreaks, such as the one in Guilford County, emphasize the prevention strategies and activities needed to maintain national and local progress toward elimination of syphilis, including innovative public health responses tailored to meet the challenge of shifting community patterns of high-risk behaviors and associated new outbreaks of communicable diseases. In addition, findings from this outbreak suggest that strengthening and maintaining screening in jails may be a useful component of syphilis surveillance and early outbreak detection, even in areas with little or no recognized syphilis transmission. References

Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 12/18/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|