|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

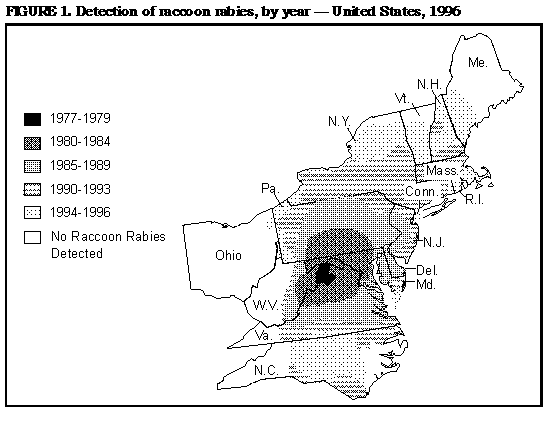

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Update: Raccoon Rabies Epizootic United States, 1996Since 1960, rabies has been reported more frequently in wild animals than in domestic animals in the United States. In 1995, wildlife rabies accounted for 92% of animal rabies cases reported to CDC; approximately 50% of these cases (3964 of 7881 total cases) were associated with raccoons (1). This report describes the continuing spread of an epizootic of raccoon rabies in affected mid-Atlantic and northeastern states and the spread into Ohio, indicating an increasing move westward despite geographic barriers. New York. Rabies was first confirmed in raccoons in New York in May 1990; since then, 7851 cases of animal rabies (6637 in raccoons and 1214 in domestic and other wild animals infected with the raccoon rabies virus variant) have been confirmed from all 62 counties in the state. Since 1990, the raccoon rabies epizootic has spread steadily northward within the state at an average rate of 25 miles per year. During 1994-1995, however, a focus of raccoon rabies re-emerged in the 11 counties that were affected first by the epizootic during 1990-1991: from 1994 through 1995, the total number of raccoon rabies cases in these 11 counties increased 245% (from 40 to 138, respectively). Cases of rabies in domestic animals also have increased substantially: during 1990-1995, a total of 158 cases were confirmed in cats, and 36 cases were confirmed in dogs. Before 1990, postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) was provided to an average of <100 persons annually in New York; in comparison, during 1990-1995, approximately 10,000 persons received PEP. North Carolina. Rabies was first confirmed in raccoons in the northeastern part of the state during 1991, probably reflecting an extension of the mid-Atlantic raccoon rabies epizootic. During 1992, cases were confirmed in raccoons in the southeastern quadrant of the state. Both epizootic foci continued to spread, and by late 1994 and early 1995, cases were confirmed in the central section of the state. In 1995, of the 875 raccoons submitted for testing, 362 (41%) were positive for rabies, more than double the number of raccoon rabies cases reported in the state in 1994 (143 cases). Vermont. Rabies was first confirmed in foxes in northwestern Vermont in February 1992 and in raccoons in southwestern Vermont in June 1994. The raccoon rabies epizootic has continued to spread northward up the Champlain basin and the Connecticut River valley; in 1995, cases were detected in all 14 counties within the state. In 1995, of 685 animals tested for rabies, 179 (26%) were positive, a 20% increase from 1994. In 1995, of the 261 raccoons tested for rabies, 104 (40%) were positive; in addition, testing was positive for 31 foxes, 38 skunks, two woodchucks, one pig, one beaver, and one cat. Rhode Island. Rabies was first confirmed in January 1994 in raccoons in Rhode Island near the state's northern border. In 1994, animal rabies cases were reported from 23 (59%) of 39 cities and towns, and by 1995, cases had been confirmed in every city and town except for the island communities of New Shoreham and Jamestown. In 1995, of 886 animals tested for rabies, 324 (37%) were positive, an 11% increase from 1994 in the proportion of all animals testing positive. In 1995, of 345 raccoons tested for rabies, 215 (62%) were positive; in addition, testing was positive for 83 skunks, nine foxes, seven cats, four cows, and one woodchuck. Maine. Rabies was first confirmed in raccoons in southern Maine and in foxes in central Maine in August 1994. Subsequently, cases have been detected in both domestic and wild animals in nine (56%) of 16 counties and 77 (17%) of 456 cities and towns in the state. From 1994 through 1995, the number of animals submitted for rabies testing increased from 351 to 736, and the number of confirmed animal rabies cases increased 10-fold, from 10 to 101. In 1995, of 117 raccoons tested for rabies, 41 (35%) were positive; in addition, testing was positive for 44 skunks, seven foxes, and one dog. Ohio. In late May 1996, the first indigenous case of raccoon rabies in Ohio was confirmed in a racoon captured in the village of Poland in northeastern Ohio, approximately 3 miles west of the Pennsylvania border. In June 1996, active surveillance of dead animals found on roads and nuisance animals reported to animal-control agencies was initiated within a 10-mile radius of the index case; however, no cases were confirmed among the 57 specimens tested. Active surveillance continues in this region. Reported by: TK Lee, DrPH, KF Gensheimer, MD, State Epidemiologist, Maine Dept of Human Svcs. RH Johnson, DVM, Vermont Dept of Health. U Bandy, MD, State Epidemiologist, State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Dept of Health. CA Hanlon, VMD, CV Trimarchi, D Morse, MD, State Epidemiologist, New York State Dept of Health. JL Hunter, DVM, JM Moser, MD, State Epidemiologist, North Carolina Dept of Environment, Health, and Natural Resources. KA Smith, DVM, TJ Halpin, MD, State Epidemiologist, Ohio Dept of Health. Viral and Rickettsial Zoonoses Br, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: The variant of rabies virus associated with raccoons has been present in the southeastern United States since the 1950s and was introduced into the mid-Atlantic region of the United States in the mid-1970s, probably as the result of translocation of animals from the southeastern United States (2). The first such case was reported from West Virginia in 1977. Infected raccoons subsequently were reported from Virginia (1978), Maryland (1981), the District of Columbia (1982), Pennsylvania (1982), Delaware (1987), New Jersey (1989), New York (1990), Connecticut (1991), North Carolina (1991), Massachusetts (1992), New Hampshire (1992), Rhode Island (1994), Vermont (1994), Maine (1994), and Ohio (1996) (Figure_1). During 1995, states in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast regions accounted for 89% (3510 of 3964) of the reported cases of raccoon rabies in the United States (1). The rapidity of spread throughout the mid-Atlantic region may reflect the density of raccoon populations associated with abundant food supplies and denning sites in urban and suburban areas (3). Although westward progression of the epizootic has been slowed by geographic barriers such as the Great Lakes, the Chesapeake Bay, the Potomac and Susquehanna rivers, and the Appalachian Mountains (4), once rabies infection becomes established in racoons in the Ohio Valley, the epizootic may spread more rapidly across the Midwest. There have been no documented human rabies cases in the United States associated with the raccoon rabies virus variant. Potential explanations for this are that first, because raccoons are large and bites to humans are likely to be recognized, rabies PEP can be administered rapidly, and second, domestic animal rabies vaccination programs have provided a barrier to infection of humans by eliminating a potential link in rabies transmission from wildlife to humans. This barrier should be maintained also through traditional public health measures such as educating the public about the importance of rabies vaccination for pets, mandatory vaccination and leash laws, and animal-control programs. The costs associated with rabies control and prevention in the northeastern United States have increased in direct relation to the spread of the raccoon rabies epizootic; these costs primarily reflect the number of PEP regimens administered. For example, in Connecticut, the estimated number of persons to whom PEP was administered increased from 41 in 1990 to 887 during the first 9 months of 1994 as the raccoon rabies epizootic spread statewide, at a median cost of $1500 per person exposed (5). Rabies control in two counties in New Jersey accounted for a cost increase of $1.2 million from 1988 (before the introduction of the raccoon rabies epizootic) through 1990 (the year the epizootic became established) (6). New methods for slowing or containing the raccoon rabies epizootic are being considered in several states. For example, oral vaccination control programs using vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein recombinant vaccine contained within baits have been implemented in trials conducted in Cape May, New Jersey; Cape Cod, Massachusetts; eastern and northern New York state; and Pinellas County, Florida (7). Implementation of such programs to prevent spread of raccoon rabies to new areas is an adjunct to traditional control methods. References

Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|