Developing a Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect Syndrome for State Health Departments

The National Syndromic Surveillance Program Community of Practice (NSSP CoP) Syndrome Definition (SD) Subcommittee examines topics of high interest to syndromic surveillance practitioners. In July 2020, the SD Subcommittee focused on health topics that affect children, including COVID infection-associated shutdowns, children being out of school, and families under increased stress. Elizabeth Swedo of CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC), Division of Violence Prevention (DVP), described a collaborative effort to develop the Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect Syndrome. She provided the reasoning and context for the definition, described the development process, and discussed obstacles, solutions, and lessons learned that syndromic surveillance practitioners can potentially apply to their work. The syndrome is available in NSSP–ESSENCE and will be added to the NSSP Community of Practice Knowledge Repository.

Background

For years, Elizabeth Swedo, a pediatrician and epidemiologist with CDC’s Injury Center, has been studying child abuse to better understand and prevent it. Swedo began her presentation during the July 2020 meeting of the SD Subcommittee by defining child maltreatment as all types of abuse and neglect of a child younger than 18 years by a parent, caregiver, or another adult in a custodial role that results in harm, the potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child.1 She listed the four common types of child abuse and neglect: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. “Unfortunately,” Swedo said, “child abuse and neglect are common. At least one in seven children have experienced child abuse or neglect in the past year,2 and this is likely an underestimate. In 2018, nearly 1,800 children died of abuse and neglect in the United States.”3

At the federal level data on child abuse and neglect are collected through the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, or NCANDS, a federally sponsored effort that annually receives and analyzes data on child abuse and neglect known to child protective services (CPS) agencies in the United States. NCANDS data are submitted voluntarily by all states, Washington, DC, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and key findings are published in the annual Child Maltreatment report series and reports to Congress. Due to reporting and publication schedules, there is often a 1–2 year lag in available data, and NCANDS detects only the most severe cases. Additional surveillance data are periodically collected by the National Incidence Study (NIS), a congressionally mandated research effort to assess the incidence of child abuse and neglect in the United States. NIS estimates the scope of child maltreatment by combining information about cases reported to CPS with data on maltreated children identified by professionals who encounter them during the normal course of their work in a wide range of agencies in representative communities. While valuable, these data are collected infrequently; for example, data for the most recent iteration of the NIS survey, NIS-4, were colected in 2005–2006 and published in 2010.

Nationally representative self-reported data on child abuse and neglect may be collected via survey, such as the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV). However, these survey data are costly to obtain and not collected with regular frequency—the most recent NatSCEV survey took place in 2013–2014 and results were published in 2015.2

Public health departments need complete, high quality, and timely data to monitor the efficacy of prevention programs, allocate resources, and evaluate trends on a granular level. Syndromic surveillance offers a progressive solution. “As you may know,” Swedo said, “syndromic surveillance offers a unique, near-real-time perspective on trends and medical conditions. As a pediatrician who spent 5 years of her career in emergency rooms and urgent cares, I know how much information can be gleaned from a chief complaint.” To obtain timely data, Swedo and her DVP collaborators reached out to colleagues in NSSP and set out to explore how syndromic surveillance could be applied. They sought to define syndromes to capture the incidence and prevalence of emergency department visits related to child abuse and neglect. This would give state and local health departments a more timely and sensitive way to monitor trends and identify changes within their jurisdictions.

Swedo and her DVP and NSSP colleagues initially planned to develop two general definitions: one for child abuse and neglect (CAN) and the second for child sexual abuse (CSA). As the group explored billing codes and free-text for visits, they soon realized that two general definitions would be inadequate to capture the nuances and that four syndrome definitions were needed. The group settled on Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect (all suspected or confirmed cases of CAN), Confirmed Child Abuse and Neglect (confirmed cases of CAN), Child Sexual Abuse (broad definition for suspected or confirmed cases of CSA in children 0–17 years), and Child Sexual Abuse Younger than 10 Years (specific definition for suspected or confirmed cases of CSA in children under the age of 10 years).

The Process

To develop each syndrome definition, Swedo and her colleagues used a four-step process:

- Identify relevant ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM, and SNOMED codes.

- Identify relevant keywords and negations using ICD codes in CCQV (chief complaint/query validation) and local-level data to generate additional terms. (They added typographical errors, misspellings, acronyms, and abbreviations and used NSSP’s R Markdown tools to identify bigrams and trigrams of frequently associated words.)

- Refine and validate each definition by engaging public health experts in syndromic surveillance from the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, Colorado’s Tri-County Health Department, and Texas Regions 2 and 3.

- Crosswalk the definitions to ensure consistency.

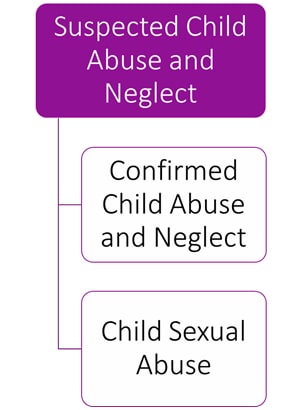

Figure 1: The Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect definition includes more specific definitions, like Confirmed Child Abuse and Neglect and Child Sexual Abuse, within it.

“Our approach to these definitions,” Swedo said, “was a bit like a Russian nesting doll, with the most specific definitions, like Confirmed Child Abuse and Neglect or Child Sexual Abuse, fitting within the broader definition of Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect” (Figure 1).

Swedo showed examples of the ICD (including perpetrator) codes; SNOMED codes; keywords; and negation terms. To align with the definition of “child sexual abuse,” they excluded assaults perpetrated by sisters, brothers, cousins, girlfriends, boyfriends, or people other than a parent or custodial adult. The team adjusted the system to exclude Spanish words like molestar, meaning “to bother,” that could appear in a chief complaint if an adolescent said his “throat bothered him,” but might have otherwise been mistaken for the English word molest.

Challenges, Solutions, and Take-aways

- Challenge—The original concept was to create a broad child abuse and neglect syndrome definition. Almost immediately, Swedo and the other epidemiologists were unsure how to handle two ICD codes: Z04.42 and Z04.72. Code “72” should be used for suspected but RULED OUT child physical abuse; similarly, “42” should be used for RULED OUT sexual abuse. Neither code, however, was being used in the prescribed way.

Solution—Use multiple definitions to handle uncertainty intrinsic to some codes and keywords in the definition. Create a suspected and a confirmed abuse definition. Include the suspected ICD codes in the Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect definition and exclude these codes in the Confirmed Child Abuse and Neglect definition.

Take-away—Creating more than one definition can give you some flexibility and make decisions easier.

- Challenge—When the identity of a perpetrator is ambiguous, how should the syndrome definition be handled? Some chief complaints are obvious (e.g., “beaten with stick by mother”) and some less obvious (e.g., “beaten with stick”). Swedo and the other epidemiologists had to decide what to do with chief complaints that would not qualify as child abuse if perpetrated by a sibling or peer but would qualify if perpetrated by a parent, guardian, or other adult in a caregiving role. They also had to decide either to include certain keywords that only appear with inclusive perpetrator terms (e.g., mother, father, aunt, uncle) or to exclude complaints with perpetrators who do not meet the definition.

Solution—After much discussion and testing of the query to see what yielded the best results, they decided to use inclusive perpetrator terms. Certain keywords and codes in their definition—like rape or assault—would only be counted if also accompanied by an adult perpetrator keyword or ICD code. This approach makes the definition specific to abuse.

Take-away—Decide on the most important aspect of your definition (for example, specificity versus sensitivity) and allow that to guide decisions.

- Challenge—How should previously identified codes be incorporated into the newly created syndrome definition? Previous research has validated the use of ICD-9-CM codes that represent ilnesses or injuries suspicious for child sexual abuse when applied to children under the age of 10 years, like genital herpes or genital bruising. Such ICD codes capture such occurences quite well when paired with age restriction but lose specificity when applied to older children.

Solution—A decision was made to include codes identified to suggest child abuse among children younger than 10 years. NSSP has the ability to limit age groups. Consequently, a syndrome definition could be tailored to children younger than 10 years.

Take-away—Take advantage of NSSP’s ability to limit age groups for definitions by creating a separate 0- to 10-year child sexual abuse (CSA) definition that includes previously validated ICD-9-CM codes for sexually transmitted infection, genital bruising, etc.

In conclusion, the Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect Query v1 is published in NSSP–ESSENCE as a Chief Complaint/Discharge Diagnosis category. The next steps are to develop and publish a confirmed Child Abuse and Neglect (CAN) query, a CSA query, and a CSA Under Age 10 Years query. In December 2020, CDC published “Trends in U.S. Emergency Department Visits Related to Suspected or Confirmed Child Abuse and Neglect Among Children and Adolescents Aged <18 Years Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, January 2019–September 2020” in MMWR using the query. Plans are also underway to do more analyses, co-develop manuscripts, and revise the definitions as needed when feedback is obtained.

Plans are also underway to do more analyses, co-develop manuscripts, and revise the definitions as needed when feedback is obtained.

The July 2020 Syndrome Definition Subcommittee call is posted here.

NSSP and NCIPC thank the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, the Texas Public Health Regions 2 and 3, and the Colorado Tri-County Health Department. Their collaboration and feedback was invaluable during the development and refinement of this syndrome definition.

Resources

CDC: Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention

Children’s Bureau: National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System

1 Leeb RT, Paulozzi L, Melanson C, Simon T, Arias I. Child Maltreatment Surveillance: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2008.

2 Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics 2015;169(8):746–754.

3 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau 2020. Child Maltreatment 2018. Available from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology /statistics-research/child-maltreatment.