Career Fire Fighter Dies and Another is Injured Following Structure Collapse at a Triple Decker Residential Fire – Massachusetts

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2011-30 Date Released: June 25, 2012

Executive Summary

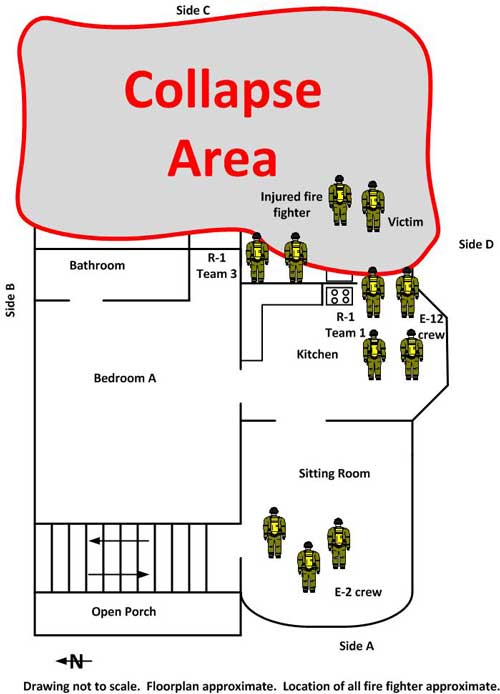

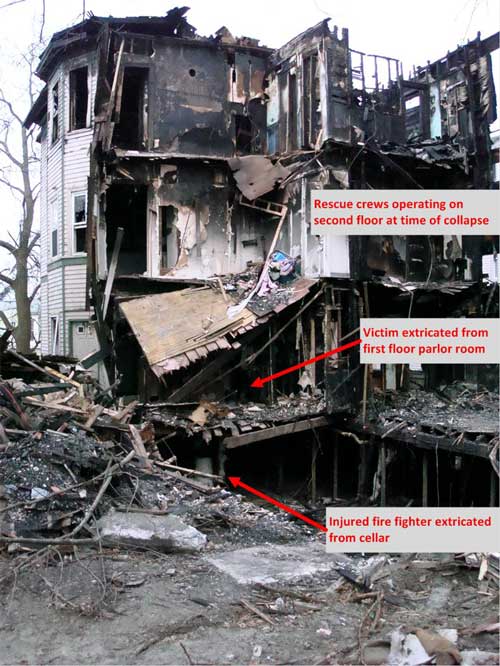

On December 8, 2011, a 43-year-old male career fire fighter received fatal injuries when he was trapped under falling debris during a partial collapse at the rear of a three-story residential structure. The victim was part of a rescue company that was conducting a secondary interior search for a reported missing resident. The secondary search was initiated approximately 30 minutes after the crews had arrived on-scene and approximately 10 minutes after fire fighters evacuated the building due to deteriorating conditions within the burning structure. The secondary search was initiated after the missing civilian’s roommate persisted in telling fire fighters that his friend was still inside, and most likely in a rear, second-floor bedroom. The collapse trapped the victim under debris on the first floor while the injured fire fighter rode the second floor down to the basement. A total of 11 fire fighters were inside the structure at the time of the collapse. Rescue operations took approximately 50 minutes to free the victim who was unresponsive. Extensive shoring was required within the unstable collapse area and crews had to breach the brick cellar wall to reach the injured fire fighter. Following the extrication efforts, fire fighters continued to search for the missing civilian. It was later determined that the missing civilian was not inside the structure at the time of the collapse. The civilian had left prior to the arrival of the fire department.

Rear view of the “triple decker” residential structure following partial cleanup of collapse debris. Search crews were on the second floor at the time of collapse.

(NIOSH Photo.)

Contributing Factors

- Civilian resident persistently stated another resident was still inside

- Fire burned well over 30 minutes before being brought under control

- Structure reacted to fire conditions in an unexpected manner

- 1890 era balloon-frame wood structure in deteriorated condition

- Instability of cellar wall and surrounding soil due to age and weather conditions

- Structural deficiencies not readily apparent

- Unusual cellar configuration for this type of residential structure

- Building inspection findings not readily available to fire department through city dispatch system

Key Recommendations

- Fire departments and city building departments should work together to ensure information on hazardous buildings is readily available to both

- Authorities having jurisdiction should ensure that hazardous building information is part of the information contained in computerized automatic dispatch systems

- Fire Departments should train all firefighting personnel on the risks and hazards related to structural collapse

- Fire Departments should use risk management principles including occupant survivability profiling at all structure fires

Hazardous building placard attached to exposure structure located just south of the fire building.

(NIOSH Photo)

Introduction

On December 8, 2011, a 43-year-old male career fire fighter received fatal injuries when he was trapped under falling debris during a partial collapse at the rear of a three-story “triple decker” residential structure. The U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident the same day. NIOSH investigators with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program contacted the fire department involved in this incident to arrange an investigation. At the request of the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) union and the fire department, the NIOSH investigation was initiated after the December holidays. On January 4, 2012, a safety engineer, a general engineer, an occupational safety and health specialist and an investigator with the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program traveled to Massachusetts to investigate this incident. During this investigation, the NIOSH representatives met with fire department officials including the Fire Chief, the Deputy Chief of Operations, the Chief of Safety and members of the Arson Unit. The NIOSH investigators also met with representatives of the IAFF local and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Assistant District Attorney representing the county. The NIOSH investigators visited the city’s dispatch center and obtained a copy of the fireground audio. The NIOSH investigators visited the incident site and photographed the structure as well as an adjacent triple decker with a similar floor plan. The NIOSH investigators conducted interviews with fire department officers and fire fighters directly involved in the fatal incident. On January 11, 2012, the NIOSH safety engineer and one investigator returned to Massachusetts to continue the investigation. Meetings were held with representatives of the U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF); Massachusetts State Police, Fire and Explosion Investigation Section; the fire department’s Chief of Training; and the city’s Division of Building and Zoning. Additional interviews were conducted with fire fighters directly involved in the incident. The NIOSH investigators inspected and photographed the victim’s personal protective clothing and self-contained breathing apparatus. The NIOSH investigators reviewed training records and standard operating procedures at the fire department. Additional photographs and building information were obtained with the assistance of the Assistant District Attorney.

Fire Department

The career fire department provides fire protection and life safety services to an area encompassing 39 square miles and a population of close to 181,000. The day time population increases to well over 200,000. The city encompasses a diverse range of structures from densely populated multi-family dwellings to residential and office high rise buildings to a mixture of manufacturing and industrial complexes. The city also contains 10 universities and colleges.1 A major east-west interstate highway passes through the city, along with multiple rail systems. The fire department provides first responder emergency medical care. Advanced life support and transportation is provided by a private health care company.

The fire department operates 13 Engine Companies, 7 Ladder Companies, 1 Heavy Rescue, 1 Special Operations unit, 1 Field Communications unit and 2 SCUBA (dive rescue operations) vehicles from 10 stations. Fire operations are divided into north and south divisions or districts with a District Chief overseeing operations within each district. The fire department employs a total of 406 uniformed personnel within the operations, fire prevention and support services divisions.

Fire fighters are assigned to work one of four operations shifts. Fire fighters work two 10-hour day shifts on consecutive days (24 hours off) followed by two 14-hour night shifts on consecutive nights, then are off for 3 consecutive days. A full shift roster includes 88 fire fighters with minimum staffing at 72.

The fire department maintains a SCUBA Dive Rescue Team trained for swift water rescue and recovery, under-water and under-ice rescue operations; and a Technical Rescue team trained for trench rescue, confined space, collapse rescue and high-angle rescue

The fire department operates on an 800 megahertz trunked radio system managed by the city. Each fire fighter is assigned a portable radio having 16 different talk groups. Emergency calls are dispatched over an operations group. The fire department also has 3 operations groups to which an incident can be assigned by the Incident Commander (per mandatory fire department procedures), allowing fireground radio traffic to occur on its own channel. Fire Prevention, Training, and Maintenance each have their own talk group. The city Emergency Communications Department receives all 911 calls originating within the city. Calls are then transferred to the appropriate dispatchers. Call receipt and dispatching are processed by a computer-aided-dispatch (CAD) system.

The fire department responded to a total of 28,150 incidents (1,435 fire and 26,715 non-fire) during 2010 and a total of 28,891 incidents (1,384 fire and 27,507 non-fire) during 2011. In 2007, the fire department received a Class 2 rating from ISO.a In the ISO rating system, Class 1 represents exemplary fire protection, and Class 10 indicates that the area’s fire-suppression program does not meet ISO’s minimum criteria.

aISO is an independent commercial enterprise which helps customers identify and mitigate risk. ISO can provide communities with information on fire protection, water systems, other critical infrastructure, building codes, and natural and man-made catastrophes. ISO’s Public Protection Criteria program evaluates communities according to a uniform set of criteria known as the Fire Suppression Rating Schedule (FSRS). More information about ISO and their Fire Suppression Rating Scheduleexternal icon can be found at the website http://www.isogov.com/about/.

Training and Experience

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts does not have prerequisite training or education requirements for an individual to become a fire fighter. Persons wanting to work as a fire fighter in Massachusetts must pass the state’s civil service test and a physical abilities test.

This municipal fire department operates its own training center under the supervision of a Chief of Training. The training center includes a burn building that allows for live-fire training using class A fuels. The burn building can be configured for multiple training evolutions to simulate residential, commercial, triple-decker and high-rise construction.

The training center provides recruit, proficiency and annual refresher training for the fire department. Recruits are selected through the state’s civil service examination process. Potential candidates must have a valid driver’s license and a high school diploma or a GED certificate. Selected candidates attend a 16-week recruit training class at the department’s training center, regardless of whether they have previous firefighting experience or not. The recruit class curriculum is equivalent to the requirements of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1001 Standard on Professional Qualifications for Fire Fighters, Fire Fighter I and Fire Fighter II.2 Recruit training is conducted at the training center with the exception of flashover simulation training, gas-fueled fire and Hazardous Materials Awareness training which is conducted at the Massachusetts Fire Academy. After completing the 16-week recruit training class, new fire fighters are on probation for 9 months and cannot work on a fire apparatus without an officer present. Recruits must pass the ProBoard Certification requirements prior to receiving a permanent assignment. Note: Prior to 2010, fire fighters completing the fire department’s recruit training class were not required to obtain ProBoard certification for Firefighter I and Firefighter II.

The training center provides the resources for each station to conduct their own Company-level proficiency training. Fire fighters are required to train at least 1-hour per work shift and must complete 8 training drills covering 8 different topics per month. Training records forms are submitted by the company officer through the District Chief to the Chief of Training. The fire department has maintained an electronic training record-keeping system since 2006. Note: Training records prior to 2006 are maintained by the fire department but were not reviewed by NIOSH investigators as part of this investigation.

Special operations training is also handled through the training center. In addition to the Rescue 1 crews, the fire department maintains one engine company (Engine 5) and one ladder company (Ladder 4) specifically trained for technical rescue operations. Note: During the NIOSH interviews, a number of fire fighters commented on the technical rescue training and how the training had enhanced the rescue operations during this incident. This fire department suffered a multiple line-of-duty death incident in 1999. The department’s training program was enhanced and the current training facility built following the 1999 incident.

Internal promotions to all ranks are handled following the state’s civil service promotion test process. Promotion examinations are given every two years. When promotions occur, the fire department conducts a 40-hour officer development training program. In addition, company officers can take Fire Officer I-IV training at the Massachusetts Fire Academy, although it is not a fire department requirement.

The victim joined the fire department in April 1994. He had been assigned to Rescue 1 in May 2010. Training records showed that the victim had completed numerous fire fighter and first responder training such as live fire training, large diameter hose lines, positive pressure ventilation, and personal protective equipment use. He had completed specialized technical rescue training in subjects such as hazardous materials, use of hazardous materials detection equipment, dive rescue operations, rope rescue operations, weapons of mass destruction/terrorism incidents, trench rescue and high angle technical rescue operations.

The injured fire fighter joined the fire department in September 1997 and was assigned to Rescue 1 in May 2005. The injured fire fighter completed numerous fire fighter and first responder training such as live fire training, positive pressure ventilation, large diameter hose lines, and personal protective equipment use. He also completed specialized training in a number of topics including rope rescue operations, use of hazardous materials detection equipment, confined space rescue, trench rescue, collapse rescue, dive rescue operations, and high angle technical rescue.

The Incident Commander joined the fire department in April 1977 and was promoted to District Chief in December 2008. He had completed numerous fire fighter and first responder training.

Equipment and Personnel

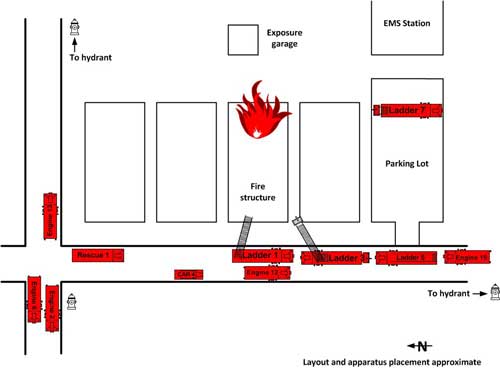

The fire department responded to the initial alarm dispatch at 0421 hours with the following personnel and apparatus:

- Engine 12 – Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters

Engine 6 – Captain and 2 fire fighters

Engine 13 – Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters

Engine 2 – Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters

Ladder 1 – Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters

Ladder 3 – 3 fire fighters

Car 4 – District Chief and Incident Command Technician

Rescue 1 – Lieutenant and 5 fire fighters

Ladder 7 as the designated Rapid Intervention Team (RIT) – Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters

A second alarm was requested by the Incident Commander (Car 4) at 0425 hours which resulted in the following personnel and apparatus being dispatched:

- Engine 7 – Captain and 3 fire fighters

Engine 15 – Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters

Ladder 5 – Captain and 3 fire fighters

Car 3 – District Chief and Incident Command Technician

At 0501 hours, the IC requested an additional engine company to knock down a fire developing in a garage behind Side C. The following personnel and apparatus were dispatched:

- Engine 4 – Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters

A third alarm was requested by the IC at 0509 hours following the collapse which resulted in the following personnel and apparatus being dispatched:

- Engine 16 – 3 fire fighters

Engine 3 – Captain and 2 fire fighters

Ladder 2 – Lieutenant and 3 fire fighters.

The Special Operations Task Force (SO1) was dispatched at approximately 0512 hours, which consisted of crews from Engine 5 (Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters) and Ladder 4 (responding in the Special Operations truck with a Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters).

Timeline

The following timeline is provided to set out, to the extent possible, the sequence of events as the fire department responded to this incident. The times are approximate and were obtained from review of the dispatch audio records, witness interviews, photographs of the scene and other available information. In some cases the times may be rounded to the nearest minute, and some events may not have been included. The timeline is not intended, nor should it be used, as a formal record of events. Note: Per standard operating procedures, the dispatcher advised the Incident Commander after 10 minutes had elapsed and every 10 minutes thereafter, during the incident.

- 0421 Hours

Local fire department dispatched for a report of a fire in a “triple decker” residential structure. E-12, E-13, E-2, E-6, L-1, L-3, R-1 and Car 4 dispatched. L-7 dispatched as the RIT. EMS crews on-scene report pulling a civilian from the structure with more civilians still inside on the second floor. - 0422 Hours

Engine 12 on Scene. Reports heavy, heavy fire at Side B and C. Initially taking 2 1/2 –inch line to rear, then E-12 radios Car 4 to report the crew is taking line to 2nd floor for report of trapping civilian. - 0424 Hours

Car 4 on scene and assumes Incident Command (IC). - 0425 Hours

IC requested 2nd Alarm. - 0426 Hours

E-7, E-15, L-5 and Car 3 dispatched. - 0441 Hours (approximate)

IC ordered evacuation of building. All companies ordered out due to reports from interior crews of deteriorating conditions on the 2nd and 3rd floors. Defensive operations put into action. - 0458 Hours (approximate)

R-1 and E-12 re-entering structure for second search for civilian. - 0501 Hours

IC requests engine company to rear for developing garage fire at Exposure C. - 0505 Hours (approximate)

Collapse at rear of structure - 0509 Hours (approximate)

IC requests 3rd alarm. E-16, E-3, L-2 dispatched. - 0510 Hours (approximate)

Victim is located and extrication has begun - 0515 Hours

Fire Chief and Deputy Chief of Operations notified and report to the scene. - 0551 Hours (approximate)

Injured fire fighter located and extrication has begun - 0602 Hours (approximate)

Victim transported to local hospital

Personal Protective Equipment

At the time of the incident, the victim was wearing turnout pants, coat, hood, helmet, boots, gloves and a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) with integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) meeting current NFPA requirements. The victim was on air at the time of the collapse and found with his facepiece on. The injured fire fighter was also found with his facepiece on. The NIOSH investigators inspected the victim’s personal protective equipment at the fire department’s fire prevention evidence storage room. While the SCBA and protective equipment suffered some damage as the result of the collapse, the personal protective equipment was not considered to be a contributing factor in this incident. The equipment was not tested or further evaluated by NIOSH.

This fire department has 10 SCBA that are equipped with a commercially available fire fighter emergency locator system. The “Pak-Tracker™” is a commercially available two-part fire fighter location system consisting of a transmitter and a hand-held receiver. In an emergency situation, search and rescue personnel use the hand-held receiver to detect the signal from a fire fighter’s transmitter. The system works on a 2.4 GHz high frequency radio signal.3 At the time of the collapse, the Rescue 1 crew members were wearing SCBA equipped with this tracking system. The system was successfully used during efforts to locate the missing fire fighters. Note: Mention of any product or trade name does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Structure

According to the city’s Division of Building and Zoning, the structure involved in this incident was a Queen Ann style three-family triple-decker residential structure believed to have been built in 1890.

The structure was located in a residential neighborhood that included many triple-decker structures on the same street and was located on the east side of a north-south street. The structure sat on a 5,000 square foot lot that sloped from rear to front toward the street. The front of the structure was approximately 10 feet above street level, with access via concrete steps at the Side A-D corner leading to a concrete sidewalk around the structure (see Photo 1 and Diagram 1). The structure incorporated typical balloon construction with a hip roof. The first and third floors were vacant at the time of the fire.

Photo 1. Front of the triple-decker residential structure viewed from the street. All structures on the east side of street on this block were elevated above street level. The first and third floors were vacant at the time of the fire.

(NIOSH Photo)

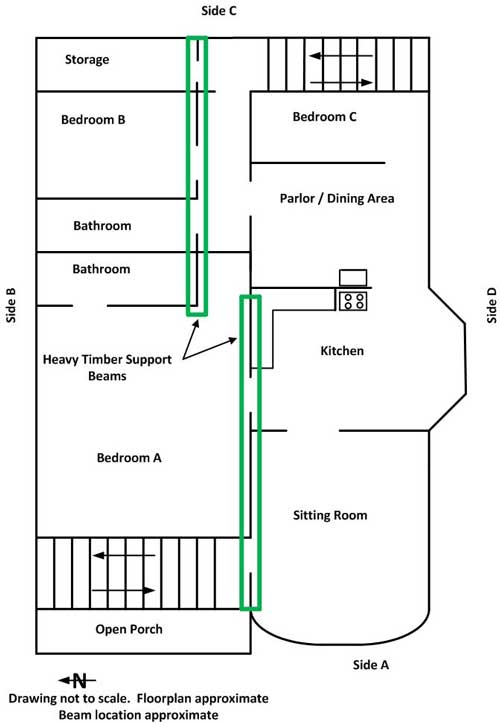

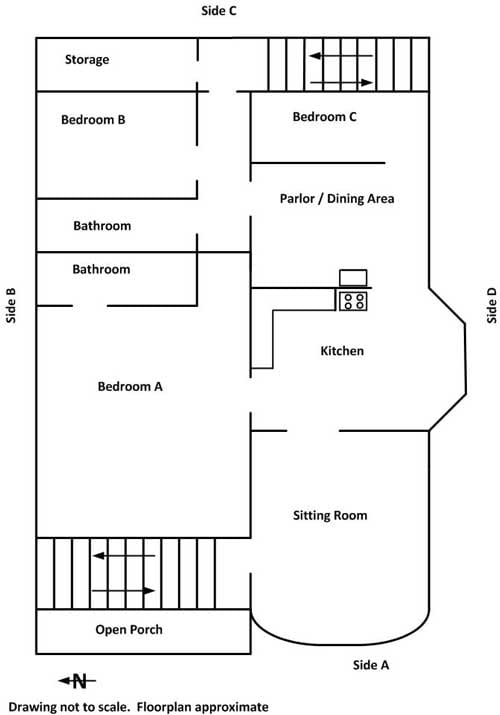

Diagram 1. Approximate floor plan of the incident structure. Each of the three occupied floors were similar in layout.

History of Triple-Deckers 3

A triple-decker (also referred to as a three-decker) is a three-story apartment building, typically of light-framed, wood construction, where each floor usually consists of a single apartment; although two apartments per floor (2) are not uncommon. 4 Additional information describing the history of triple decker construction in the north-east can be found in Appendix One.

Each level included an open porch at the front that provided a view of the street. Each porch was accessed from the interior stairwell located at the Side A/B corner. An enclosed stairwell was also located in the rear at the Side C/D corner. The rear stairwell provided access to the basement.

According to the city building officials, the structure had been owner occupied until 1990, after which it was used as a rental property. The structure had multiple owners over the years. The structure had undergone foreclosure in 2008. The structure was in a state of general dis-repair and in 2011, the current building owner had been cited by the city for a number of violations of the Massachusetts general laws, Standards of Fitness for Human Habitation. Building and sanitary code violations included problems with heating, plumbing, trash accumulation, rodent infestation and general conditions. The structure had a history of plumbing-related water damage issues and water damage to the third-floor ceiling indicating roof leakage. The first and third floors were unoccupied at the time of the fire. The residential structure to the north was occupied. A residential structure to the south had been the scene of a fire just a few months prior to this incident and was vacant and had been marked by the fire department as a hazardous structure. The fire-damaged structure to the south was built by the same builder during the same time period as the structure where the incident occurred. The floor plan and construction features were very similar and NIOSH investigators were able to access the vacant structure to observe the construction features and floor plan features during this investigation. Note: There were reports (unconfirmed by NIOSH investigators) that the last remaining occupants had recently vacated the incident building and nobody was supposed to be living in the building at the time of the fire.

The structure featured typical balloon frame construction and measured roughly 28 feet wide by 50 feet long. It was built over an unfinished basement. The basement walls were of mixed construction. The lower portion of the basement walls were stacked field stone. The top portions of the walls, (extending above ground level) were constructed of brick and mortar (see Photo 2 and Photo 3). Some of the building code violations cited by the city included cracks and deterioration in the exterior brick walls.

The structure was supported by the exterior walls resting on top of the basement walls and by two heavy timber beams running from front to back near the center. Each beam spanned approximately one-half of the length of the structure and were likely offset to provide support for the interior load bearing walls (See Diagram 2 and Photo 4).

Photo 2. View of the D-side basement wall. Note the brick and mortar wall laid over top of the field stone. View is close to the area where the injured fire fighter was extricated.

(NIOSH Photo)

Photo 3. Photo shows the basement wall in the vacant structure located adjacent to the fire structure. This structure was built during the same time period as the fire structure. Photo was taken at the Side A/D corner.

(NIOSH photo.)

Photo 4. Yellow arrows indicate the two heavy timber support beams running front to rear and located near the center of the structure. White arrows indicate tubular metal support posts commonly referred to as lally columns or lally posts. Note the off-set between the two support posts as indicated by the two supports at the lower center of the photograph.

(NIOSH Photo)

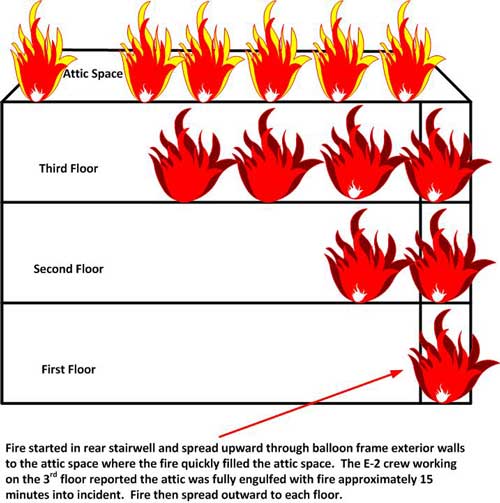

One distinguishing feature of this triple decker was that the entire structure was built over the underground basement. Fire department officials stated that a more common triple decker construction feature in the area was for the rear stairwell and porch or storage areas to be built over solid ground. Fire department officials also reported that it was common for fires to start in these rear stairwell areas, especially in vacant and dilapidated structures. The fires would commonly result in the rear stairwell and porch or storage areas, which were built over solid ground, collapsing but the main portion (living area) of the structure would most often remain standing. Fires at the rear of a triple decker traditionally resulted in the fire rapidly spreading upward through the balloon construction through the exterior walls and into the attic area. Fires that burned for an extended period of time would result in considerable fire spread and damage to the third floor, less fire spread and damage to the second floor and minimal fire spread and damage on the first floor. Aggressive fire fighting tactics at the rear and inside the upper levels usually resulted in saving the structure. The fire department estimated that they had responded to 150-160 fires in triple decker residential structures during 2011.

Following the fire, local and state fire investigators determined that the collapse was unusual for the type of building and size of the fire. Due to the unexpected collapse, both the city and state commissioned engineering analysis of the structure in an attempt to identify the cause(s) of the collapse. The main support beams (see Diagram 2 ) were examined and found that they were not unduly damaged by the fire. The support beams were determined to not have been the cause of the collapse. Further analysis revealed that Side D foundation wall near the C/D corner had blown outward at some point during the incident, possibly due to the deteriorated condition of the mortar joints and the general decay of the wall. The resulting loss of support when the foundation wall gave way caused the rear of the building to collapse. This is consistent with eye-witness reports from fire fighters on scene who stated that the C/D corner collapsed. Photographs taken by state fire investigators following the fire showed the Side D wall collapsed outward with debris located near the fence at the property line to the south (see Photo 5).

Photo 5. Photo taken from the rear of the structure just hours after the collapse. The left side of photo shows the remains of the collapsed portion of the Side D wall.

(Photo courtesy of the State Fire Marshal’s Office)

NIOSH investigators met with officials with the city’s Division of Building and Zoning to discuss the structure. During this meeting, it was discussed that the area had experienced rainfall in excess of 117 percent of normal precipitation resulting in saturated ground conditions.5 It was also discussed that the lot sloped from rear to front and the backfill at the rear put pressure on the Side C foundation wall. Three 2 ½-inch hose lines were also in operation at the rear and on Side D throughout the incident, further adding to the saturated ground conditions.

Weather

At approximately 0426 hours, the weather in the immediate area was reported to be 33.8 degrees Fahrenheit with a dew point of 32.0 degrees F. and relative humidity of 93 percent. Winds were from the North-West at 28.8 miles per hour with gusts reported at over 44 mph.6 Light rain and snow was reported in the immediate area. At approximately 0500 hours, recorded wind speeds had increased to over 33 mph with gusts over 42 mph. Wind conditions during the fire contributed to the fire threatening exposures on Sides B, C, and D. Fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH investigators reported fire impinging on the Side D exposure building.

Investigation

At 0421 hours on Thursday morning, December 8, 2011, the city fire department was dispatched for a report of a fire in a triple decker residential structure. This type of residential structure is common throughout the city and the fire department routinely responded to this type of box alarm. The fire was first reported by members of an EMS crew working at a nearby station. The EMS crew was alerted to the fire when they smelled the odor of smoke in their facility. After checking throughout their facility, they looked outside. The EMS crew observed fire at the rear of the nearby residential structure and called 911 at 0421 hours to report that the second and third floors were heavily involved. The EMS crew also reported that they pulled one civilian from the structure and there were additional civilians still inside on the second floor. Note: The EMS personnel assisted one individual from the structure but did not enter the immediate area at the rear of the second floor where the second resident was reported to have been and could not have known whether anyone was actually there or not. The dispatch center also received multiple calls from local residents reporting a fire in the area. A total of 8 fire apparatus and 30 fire fighters were dispatched on the first alarm. The dispatch included Engine 12 (E-12), Engine 6 (E-6), Engine 13 (E-13), Engine 2 (E-2), Ladder 1 (L-1), Ladder 3 (L-3), Rescue 1 (R-1) and Ladder 7 (L-7) as the designated Rapid Intervention Team (RIT). A District Chief (Car 4) and a Command Technician responded in the District Chief’s command vehicle. While companies were enroute, dispatch updated the alarm to include information reporting that a civilian was missing and possibly still inside the structure. Car 4 reported that fire was visible while they were still enroute, and confirmed that this incident was going to be a working fire. Radio traffic was switched to Operations Channel B (the fireground channel).

Engine 12

Engine 12 was the first company to arrive on-scene. The crew consisted of a Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters. They could see fire and smoke as they approached from the north and the E-12 Lieutenant radioed that heavy, heavy fire was showing on Sides B and C when they arrived on-scene at 0422 hours. The E-12 Lieutenant radioed that they were taking a 2 ½-inch hose line to the rear. E-12 was staged across the street from the burning structure. A civilian immediately came up to E-12 and told the driver that his roommate was still inside the triple decker on the second floor. The E-12 Lieutenant then radioed to Car 4 that he had a report of someone on the second floor so he was taking a hand line to the second floor and they would need a water supply immediately. The E-12 Lieutenant and fire fighter pulled a 1 ¾-inch pre-connected hand line and advanced up the stairs to the second floor. They were able to advance into the second floor but only had enough hose to reach to the kitchen (see Diagram 1). Smoke conditions were light at the front of the structure. They could see fire burning in the rear on the second floor. The E-12 crew worked in this area for several minutes. They were able to hit the fire with water from their hand line and were able to darken down the fire. They used straight stream water and left the windows intact as they were knocking down the fire.

Car 4

The District Chief for the South District (Car 4) observed fire while enroute and confirmed to dispatch that they had a working fire. Car 4 arrived on scene at 0424 hours and assumed Incident Command. The command vehicle was parked in the street across from the structure behind E-12. He observed that the fire was threatening exposures on Sides B, C, and D so he immediately radioed dispatch (at 0425 hours) to request a second alarm.

The IC observed what he described as the classic burn pattern for a fire at the rear of a triple decker structure. Fire was burning at the rear of the structure from ground to roof. He observed little extension into the first floor with some fire extension into the second floor and more extensive fire burning on the third floor. Note: Due to the balloon construction, the fire rapidly traveled from the first floor up through the exterior walls to the third floor. This burn pattern usually results in little fire damage on the first floor, more fire damage to the second floor than the first, and extensive damage to the third floor and roof (see Diagram 3).

Engine 2

Engine 2 was the second due engine company. The crew consisted of a Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters. They observed fire and smoke as they approached the scene. They positioned E-2 on the side street to the north of the structure (see Diagram 4). They laid a 4-inch supply line from a hydrant near the corner of the intersection to E-12. After helping establish water supply to E-12, the E-2 Lieutenant and both E-2 fire fighters pulled a second 1 ¾-inch hand line off E-12 and advanced it up the front entrance to the 3rd floor. They advanced their hose line into the bedroom on Side B (north side of the structure) and knocked down the visible fire in the bedroom. The Lieutenant was carrying a pike pole and he had one of the E-2 fire fighters begin pulling ceiling in the bedroom. The fire fighter opened up several 4 foot by 4 foot holes in the ceiling and the E-2 Lieutenant reported observing that the attic space was fully involved with fire visible from rear to front. The E-2 Lieutenant radioed to the IC that another hose line was needed on the 3rd floor. At this point, E-2 crew was the only company on the 3rd floor.

While working on the 3rd floor, the E-2 Lieutenant noticed that the operator of Ladder 1 had the aerial ladder up and positioned outside the Side A windows.

Ladder 1

The Ladder 1 crew was the first due ladder company. The crew consisted of a Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters. They positioned L-1 in the street in front of the burning structure. They immediately set up the aerial ladder to access the second floor front porch. The L-1 Lieutenant and one fire fighter immediately climbed up the aerial ladder and began to search the second floor for the civilian who had been reported to be missing. The other L-1 fire fighter stayed at the turntable. They went to the right and walked through the front room to the kitchen but could go no further due to the amount of fire in the rear of the structure. They searched the bedroom on side B. The E-12 and Rescue 1 crews were already on the second floor searching for the civilian.

The L-1 Lieutenant and fire fighter went to the third floor to continue searching. Visibility in the front of the third floor was clear. The rear was full of fire. They encountered another crew on the third floor. The L-1 crew searched as much of the third floor as they could, then went down to the stairs and proceeded to the street. The aerial ladder was repositioned to the roof and the L-1 Lieutenant climbed the aerial ladder to the roof where he observed that the roof at the rear of the structure was burned off. The roof at the front was sagging and appeared to be unstable. While the Lieutenant was observing the roof conditions, the IC ordered over the radio for the building to be evacuated. The air horn on L-1 was used to sound an evacuation tone.

Engine 6

Engine 6 was the third due engine company and parked on the side street north of the incident scene (across street from E-2). E-2 already had connected supply lines to the hydrant when E-6 arrived. The E-6 crew reported to the IC and were assigned to pull a 2 ½-inch hand line and assist the E-13 crew at the rear. The E-6 crew pulled a 2 ½-inch hand line with a smoothbore nozzle from E-12 to Side D to protect the exposure building. The E-6 Captain radioed the IC that they were holding the Side C exposures but were not able to put water on the structure due to the fire conditions threatening the exposure. The high winds were blowing the heavy fire erupting from the structure toward the Side D exposure. The E-13 crew was working Side C where exposures were also threatened.

As the fire intensified, electrical utility wires running between the structure and a utility pole behind the structure caught fire and dropped from the pole into the back yard and started to arc. The E-6 officer talked to the IC about getting the utilities shut off. One of the E-6 fire fighters ran low on air so the crew went back to change their air cylinders. They drank water and rehabbed for a few minutes. The structure collapsed while the crew was returning from getting new air cylinders.

Ladder 7

Ladder 7 was the designated RIT on the dispatch per department guidelines. They arrived on-scene before Ladder 5 and L-7 was able to position in a parking lot adjacent to the exposure building adjacent to Side D (south of the fire building). The L-7 crew reported observing flames extending 15-20 feet above the roofline as they were positioning their apparatus. This location provided a good position for ladder pipe operations at the rear of the burning structure. The L-7 Lieutenant radioed the IC to tell him they had positioned L-7 in a location where they could direct a master stream onto the rear of the structure. After discussing their position, the IC instructed L-7 to remain as the RIT. During this time, the North District Chief (Car 3), who was dispatched on the second alarm, arrived on-scene, and was assigned as the Division C and Division D supervisor. After Car 3 sized up the locations of the ladder companies, he suggested to the IC that L-7 should be put into operation. After a subsequent face-to-face discussion with the L-7 Lieutenant and Car 3, the IC instructed L-7 to put their master stream into operation. Ladder 5 was later designated to be the RIT. L-7 was set up and flowed water over top of exposure building on side D onto the burning triple decker. Water supply for L-7 was established by running a 3-inch hose line from E-15 up through the parking lot to L-7. A 2 ½-inch hose line was also run to L-7 for water supply from E-15. Note: The parking lot where Ladder 7 set up had been part of an old fire station that had previously been closed. The building was being used as an EMS station.

The L-7 master stream was put into operation and began lobbing water over top of the exposure building toward the rear of the burning structure. Note: L-7 was a 100-foot rear mount aerial platform apparatus. The L-7 Lieutenant and one fire fighter were in the elevated platform where they had a view of the roof of the burning building (see Diagram 4). The master stream was being sprayed directly into the oncoming high winds which partially broke up the water stream. The high winds pushed part of the water back onto the exposure building, helping to protect the exposure. The master stream was flowing at 600 – 800 gallons per minute.

When the L-7 master stream was put into operation the roof of the burning building was still intact. Shortly after the master stream was put into operation, the roof at the rear of the building began to collapse. The crew stated to NIOSH investigators that they thought this was a normal process for a triple decker fire and the master stream quickly knocked down the fire venting through the roof.

After the collapse and subsequent PAR, the L-7 crew walked to the C/D corner where they observed how bad the collapse had been. The crew engaged in the rescue operations.

Engine 13

Engine 13 was the fourth due engine company, with a crew consisting of a Lieutenant and 2 fire fighters. E-13 staged on the side street north of the burning triple decker and walked to the front to report to the IC. Ladder 1 and Ladder 3 were already on-scene and positioned in the street in front of the structure. The E-12 crew was already inside with their hand line. The IC instructed the E-13 crew to take a 2 ½-inch hand line to the rear. They pulled a 2 ½-inch hand line off E-12 and pulled it up the steps and along the Side D walkway towards the rear. They worked the hand line onto the Side D exterior wall and also onto the exposure building. When the E-6 crew arrived with another 2 ½-inch hose line, the E-13 crew moved to Side C and worked their 2 ½-inch hand line on the side C exterior wall. Engine 13 Lieutenant reported that they were pulling a second 2 ½-inch line from E-12 to the rear. The E-13 Lieutenant reported that fire was now burning on the third floor from the rear to the front and the windows were starting to vent due to the heavy fire. E-15 brought a third 2 ½-inch hand line to the rear yard.

The E-13 went back to get new air cylinders and returned with a length of 1 ¾-inch hand line to connect to their 2 ½-inch line for pending mop-up operations. The Lieutenant walked back to the C/D corner to observe the conditions at the rear and was walking back to the rest of his crew when the rear of the structure collapsed. During this time period, the Lieutenant recalled seeing lights of the Rescue 1 crew through the second story windows operating inside on the second floor.

Ladder 3

Ladder 3 was the second due ladder company. L-3 drove past L-1 and parked in the street where they could access the A-D corner of the burning building. L-3 was set up for master stream operation and flowed 600 – 800 gallons per minute of water on the roof and along the side D of the burning triple decker.

Rescue 1

Rescue 1 was dispatched on the first alarm with a crew of a Lieutenant and 5 fire fighters. The crew observed a large volume of fire at the rear of the structure. Rescue 1 staged in the street just north of the burning structure. Medics who were on-scene told the R-1 crew about the reports that a civilian might still be inside on the second floor. Note: Normal procedure is that the rescue crew will split up into teams of two or three, depending upon staffing. One team will go to the rear and another team will go to the front to size up the situation. Because of the reports of the missing civilian, the R-1 Lieutenant told his crew that everyone would go to the second floor to search for the civilian. The R-1 Lieutenant and one fire fighter formed Team 1. The Victim and the injured fire fighter formed Team 2 and the other two R-1 fire fighters formed Team 3. When they reached the second floor, Team 1 went to the left (Side B) and Team 2 went to the right (Side D) to search. The windows were vented as the teams came to them. Team 1 carried a thermal imaging camera and used it to scan the area but did not observe any evidence of a civilian. Due to the fire conditions on the second floor, the R-1 teams could not advance through the dining room area (see Diagram 1).

Engine 7, first due on the second alarm, was ordered to secure a water supply and bring another supply line to E-12. Engine 15, second due on the second alarm, was instructed to secure a water supply and bring a supply line to L-7. After supplying water to L-7, the E-15 crew took a 2 ½-inch hand line from L-7 to the rear of the burning building.

10 Minute Benchmark

The dispatcher notified the IC that 10 minutes had transpired (at 0431 hours). The IC reported heavy fire, crews were working to control the primary exposures and the primary search was underway.

The Rescue 1 Lieutenant radioed Command to report that the search of the second floor was negative as far as they could search and conditions were deteriorating with the ceilings in the rear of the second floor starting to collapse. The Rescue 1 Lieutenant reported that Rescue 1 was moving to the 3rd floor. While still on the second floor, the R-1 crew heard radio transmissions about the falling electrical utility wires at the rear of the structure.

The R-1 Lieutenant decided to go the basement to locate the breaker box and shut off the electrical power. The stairway to the cellar was located at the rear and the Lieutenant could not access the stairway due to the amount of fire burning at the rear on the first floor. The fire fighter with the Lieutenant on Team 1 joined up with Team 2 and the three R-1 members went up to the third floor to continue searching.

The Safety Officer radioed dispatch that he was responding to the scene at 0432 hours.

The E-2 Lieutenant radioed Command that they had a hose line on the 3rd floor to back up the Rescue 1 crew. The E-12 Lieutenant radioed Command that the E-12 crew was continuing to work the hose line from their position in the kitchen.

The Rescue 1 Lieutenant radioed Command and told him that there was heavy fire at the rear of the building and the fire was starting to drop down into the first floor. He also stated that he did not believe there were any hose lines in place yet (on the first floor).

The IC radioed the E-13 Lieutenant and asked for a status report on the three exterior 2 ½-inch hose lines in operation on Sides C and D. The IC stated that he wanted a crew to take a hose line interior on the 1st floor. The E-13 Lieutenant reported that all three hose lines were needed to control the fire at the rear of the structure and they did not have the staff to send another crew to take a hose line into the 1st floor. He also reported that the fire was venting through the roof at the rear.

The IC then directed the E-7 crew to take a hose line to the 1st floor. The E-12 Lieutenant radioed Command to report that the ceiling was starting to fall on the B/C side at the rear of the second floor. Soon after, the E-12 Lieutenant radioed that the crew needed to come outside to change out their air cylinders and E-12 was leaving their hose line in place on the second floor.

The E-2 Lieutenant radioed that there was heavy fire coming through the ceiling on the 3rd floor and they needed another hand line on the 3rd floor at Side A. The IC instructed E-2 to get off the 3rd floor and take all companies off the 2nd and 3rd floors.

Dispatch asked Command if he wanted a building evacuation tone (warble tone) to evacuate the building. The IC replied that he just wanted crews to get off the 2nd and 3rd floors.

The IC radioed Rescue 1, Engine 12 and Engine 2 for their status. All Rescue 1 teams were outside preparing to take a line to the first floor to attack heavy fire at the C/D corner. Engine 12 reported they were on the porch at the first floor. Engine 2 reported they were coming out at the first floor Side A.

Ladder 3 radioed Command and reported that the rear porch was starting to collapse. The Rescue 1 Lieutenant radioed Command to tell him that there was another report from the civilian about his roommate being inside the structure. Soon after, the IC radioed dispatch and asked for an evacuation tone. As the E-2 crew descended to the ground level, soffit near the A/D corner began to fall and the crew had to avoid being struck by the falling debris.

20 Minute Benchmark

After the evacuation tone was sounded, the dispatcher radioed Command to tell him that 20 minutes had elapsed (0441 hours). The IC radioed for all companies to stand by for a personal accountability report (PAR). The PAR determined that all crews were present and accounted for.

After the roll call, the E-2 and E-12 crews pulled two 2 ½-inch hose lines off E-12 and took them to a hydrant (located south of the structure) for additional supply lines for E-12. Ladder 1, Ladder 3 and Ladder 7 were put into operation for master streams.

Engine 6 radioed Command to report that an energized power line had fallen at the rear of the structure and the crews were moving back from the area. The E-6 Captain also reported that a garage exposure at the rear was on fire.

Ladder 7 radioed Command that their master stream was set up and in operation at the C/D corner and that they needed more water pressure. Crews worked to stretch additional supply lines to L-7.

Engine 15 radioed Command and reported that the heavy fire at the rear of the structure was knocked down.

The IC radioed Ladder 5 and instructed the Captain that L-5 was now the RIT.

The Safety Officer (Car 7) arrived on scene at 0449 hours. He radioed Command to advise him that live power lines were down at the rear of the structure.

The IC radioed dispatch and asked for a status report on the electrical company to turn off the power. The dispatcher reported that the power company had been contacted at 0436 hours.

While outside in the street, the R-1 Lieutenant heard discussions involving a civilian insisting that his friend was still inside the burning structure. The civilian said he believed the missing person was in the bedroom on the second floor near the rear C/D corner. Both the R-1 Lieutenant and one of the R-1 crew members talked to the civilian separately to see if they were getting the same information. Because the civilian was insisting that his friend was still inside the structure and likely to be in the rear bedroom, the R-1 Lieutenant talked to Command about taking the R-1 crew back inside. The Safety Officer also joined the discussion about the possibility of a secondary interior search. The heavy fire at the rear of the building was knocked down. There were reports of ceiling collapses on the 2nd and 3rd floors but a structural collapse was not considered likely since triple decker structures typically (historically) had not collapsed under the existing conditions. The decision was made that R-1 would conduct a second search on the second floor.

The IC radioed E-2 and E-12 to get their status. Both crews reported that they were working on water supply for the ladder trucks. The IC stated that he needed an engine company to back up Rescue 1 who was preparing to re-enter the structure for a secondary search. The E-2 Lieutenant said they would back up Rescue 1. The IC instructed E-2 and E-12 to back up the R-1 crew with hose lines. The secondary search was focused on an area at the rear of the second floor that the fire department had not been able to reach before the structure was evacuated.

30-Minute Benchmark

The dispatcher notified Command that 30 minutes had transpired (at 0451 hours).

The E-12 Lieutenant radioed Command and discussed that they had left a hose line on the second floor that they could follow back in to the second floor. The IC confirmed the assignment to back up Rescue 1.

The IC radioed dispatch and gave a status report indicating that the exterior fire was knocked down, there still was heavy fire in the second and third floors and the attic and Rescue 1 was going back inside for a secondary search for the missing civilian.

The R-1 crew followed the hose line that E-12 had left in place up the front stairs to the second floor. Debris started to fall as the ceiling over the stairway started to collapse. The R-1 crew again split into three teams of two. There was no fire or heat and little smoke at the front on the second floor. The Victim and the injured fire fighter again teamed up (Team 2) and moved in first and advanced through the kitchen toward the rear bedroom near the C/D corner. The R-1 Lieutenant and one fire fighter (Team 1) followed them toward the kitchen with the third R-1 team behind. As the R-1 teams advanced through the kitchen, they encountered deteriorating conditions. The parler / dining room was full of smoke and fire could be seen in the rear. The E-2 crew followed the R-1 crew back inside the structure. They observed that one of the hose lines was leaking and radioed the E-12 pump operator to shut down the lines one at a time so that they could determine what line needed to be shut down and fixed. The E-12 crew also followed the R-1 crew back inside and passed the E-2 crew on the stairwell.

Car 3 instructed E-15 to use their 2½-inch hose line to hit the garage. The E-15 lieutenant replied that they would hit the garage as soon as the electricity to the downed power line was turned off. The IC radioed dispatch and asked for another engine company to take care of the garage exposure fire. Engine 4 was dispatched as an extra engine company to handle the garage fire.

E-2 radioed Rescue 1 Team 3 to advise them that the ceiling was starting to collapse in the stairwell at the 3rd floor. R-1 Team 3 had to slow their advance up the stairs because of the falling debris.

The R-1 Team 2 (the Victim and the injured fire fighter) and Team 3 were searching the parlor / dining room and the R-1 Lieutenant and R-1 fire fighter were just at the doorway separating the kitchen from the parlor when the rear of the structure collapsed. The E-12 crew was just behind the R-1 Lieutenant and fire fighter in the kitchen with the 1 ¾-inch hose line. The E-2 crew was climbing the stairs and had just reached the second floor when the collapse occurred (see Diagram 5).

The Safety Officer called Command with an urgent radio transmission stating that the rear of the building has collapsed. The E-2 Lieutenant radioed that the 3rd floor was starting to collapsing. Note: The rear of the structure collapsed just as the E-2 crew reached the second floor. The E-2 Lieutenant (who did not yet know that the rear of the building had collapsed) observed two of the R-1 crew retreating from the kitchen and observed that they appeared to be stunned. The IC immediately ordered everyone to abandon the search and evacuate the building.

The E-13 Lieutenant was walking along the sidewalk at side D when the collapse occurred. He radioed Command and reported that the Side D wall had just collapsed. The IC again radioed for Rescue 1 to get the crew and get out.

The R-1 Team 1 fire fighter grabbed one of the R-1 Team 3 fire fighters and pulled him back into the kitchen. The E-12 Lieutenant grabbed the other R-1 Team 3 fire fighter. Both R-1 Team 3 fire fighters were stunned by the collapse. One of the R-1 Team 3 fire fighters had his helmet knocked off during the collapse. The R-1 crew moved back from the collapse area and started down the stairs to regroup. When they got outside, they realized that two of the R-1 crew (Team 2) were missing so the R-1 Team 1 rushed back to the second floor and met the E-12 crew who were still in the kitchen putting water on the collapse area. The R-1 Lieutenant immediately began searching the debris pile to look for the missing fire fighters.

Diagram 5. Approximate location of crews on the 2nd floor at time of collapse.

The E-13 Lieutenant radioed Command and reported that they could hear a PASS device in the debris. The IC continued to call for Rescue 1 over the radio. The Safety Officer radioed Command that he had the Rescue 1 Team 3 crew outside the front door. Car 3 radioed Command to report that E-13 had a 1 ¾-inch hose line and were standing by at the doorway on side D near the collapse area ready to go inside to search for the origin of the PASS device.

Another PAR was taken which confirmed that the two Rescue 1 members were missing. The E-13 crew took their 1 ¾-inch hand line in through the front door and started to search for the location of the PASS device. The E-13 crew was the first crew to re-enter the structure after the collapse.

40 Minute Benchmark – Rescue and Recovery Operations

The dispatcher radioed Command to report that 40 minutes had elapsed (0501 hours). The IC radioed dispatch to request a third alarm.

The E-2 Lieutenant and two E-2 fire fighters went back to the second floor where they soon found an R-1 helmet in the kitchen. Note: The helmet was later determined to belong to one of the R-1 crew that the E-2 crew had observed backing out of the kitchen just after the collapse. They observed that the rear half of the structure had completely collapsed. The E-2 Lieutenant heard a PASS device sounding and he immediately radioed a Mayday. The E-2 crew quickly determined that the PASS was below them so they descended the front stairway to the first floor.

Someone was sent outside to R-1 to retrieve a “Pak-Tracker™.” The R-1 crew used the “Pak Tracker” and quickly got a reading indicating that a fire fighter was trapped in the debris below them. The fire fighters quickly rushed to the first floor to locate the missing fire fighters. E-13 fire fighters had entered the collapse area from Side D through a void that had opened in the side D wall. The E-13 crew was the first to locate the Victim. He was partially buried in the debris and fire fighters observed reflective trim on his turnout gear showing through the debris. The Victim’s PASS device was also sounding which aided in locating him. After initial efforts to free the Victim by hand, it was quickly determined that an extrication would be required, since his legs were pinned by heavy timbers. Rescue tools including jacks, airbags and support struts were quickly brought inside. Part of the Side D wall was leaning inward and had to be shored up to stabilize the wall and make the area safe for the rescue crews. Gasoline-power saws were brought in to cut through the floor joists and other wooden debris. The rescue crews experienced problems with the power saws running due to the smoke and dust in the area so battery powered saws were put into service. The E-2 crew helped the L-5 crew breach the wall in the Side B bedroom closet to reach the location where the Victim was trapped under debris.

The Victim was pinned in a sitting position with floor joists across his upper body. His legs were buried under debris and extended through the collapsed floor. The R-1 Lieutenant and one fire fighter went into the cellar to work from below to free the Victim’s legs. At one point, the Victim’s facepiece was removed and air could be heard escaping from the mask mounted regulator. The facepiece was replaced on the Victim’s face as crews continued to work to free him. Car 3 was re-assigned at the Rescue Group Supervisor for the rescue and extrication effort to free the Victim.

Other fire fighters began searching for the second R-1 Team 2 fire fighter who was still missing. The IC radioed dispatch for the Special Operations Task Force to be dispatched.

50 Minute Benchmark

Dispatch radioed Command and stated that 50 minutes had elapsed. The dispatcher also reported that the Special Operations crew was in-route.

The IC radioed for all crews to stand by for another personal accountability report.

The Fire Chief (Car 1) and the Deputy Chief of Operations (Car 2) were notified at 0515 hours and immediately responded to the scene.

Fire fighters on the outside of the structure heard a low air alarm sounding in the debris pile. An “all quiet” was called so that fire fighters could locate the location of the sound. Car 2 arrived on-scene and met with Command on side D. The IC (Car 4) discussed the incident situation with Car 2 and Incident Command was transferred to Car 2. Car 4 was assigned Division D to manage the remaining fire fighting operations.

The Special Operations Task Force team (Engine 5 and Ladder 4 crews) arrived on-scene and were instructed to breach the cellar wall near the A/D corner to gain access to the cellar to work on extricating the injured fire fighter (see Photo 6). Fire fighters took out a window in the foundation wall near the A/C corner and enlarged the opening for access into the basement (see Photo 7). The Special Operations team leader (the Engine 5 Lieutenant) went inside the basement to size up the rescue operation. Limited access was established at the opening in the foundation wall to control who was going in and out of the basement.

The Victim was removed from the building and transported to the local hospital at 0602 hours. The injured fire fighter was removed and transported to the hospital approximately 20 minutes later.

Photo 6. Locations of Victim and injured fire fighter post collapse Photo taken after partial cleanup of the debris.

(NIOSH Photo.)

Photo 7. Arrow marks location where foundation wall was breeched to access the cellar to extricate the injured fire fighter.

(Photo provided by the district attorney’s office)

Fire Behavior

According to federal and state fire investigators, the fire originated in the structure’s first floor rear stairwell due to undetermined causes. The dispatch center received multiple phone calls reporting the fire.

Indicators of significant fire behavior

- An early morning fire may have burned for some time before being reported

- EMT crews observed 2nd and 3rd floors fully involved and phoned dispatch

- Fire and smoke clearly visible to first responding crews

- First arriving company (E-12) reported “ heavy, heavy” fire at rear

- First interior crew (E-12) observed heavy fire at rear of second floor from kitchen

- Second interior crew (E-2) observed fire in Side B bedroom at front of 3rd floor

- E-2 Lieutenant observed heavy fire in attic when 3rd floor ceiling was pulled

- E-2 Lieutenant reported heavy fire in attic from rear to front

- E-13 Lieutenant working exterior hose line at rear reported windows on 3rd floor starting to vent

- L-7 crew observed fire vent through roof at rear of structure

- R-1, E-12 and E-2 officers reported ceiling starting to collapse on 2nd and 3rd floors

- IC ordered building evacuation 20 minutes into incident

- R-1, E-2 and E-12 crews re-enter structure for secondary search approximately 30 minutes into incident

- Safety Officer observes structure collapse at C/D corner

- E-13 Lieutenant observes Side D wall collapse outward

- E-2 Lieutenant observes 3rd floor stairwell starting to collapse

- Partial collapse at rear of structure traps two members of R-1 crew.

Contributing Factors

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to this fatality:

- Civilian resident persistently stated another resident was still inside

- Fire burned well over 30 minutes before being brought under control

- Structure reacted to fire conditions in an unexpected manner

- 1890 era balloon-frame wood structure in deteriorated condition

- Instability of cellar wall and surrounding soil due to age and weather conditions

- Structural deficiencies not readily apparent

- Unusual cellar configuration for this type of residential structure

- Building inspection findings not readily available to fire department through the city dispatch system

Cause of Death

The Medical Examiner’s Certificate of Death listed the immediate cause of death as blunt trauma and compression injuries of the neck and torso.

Recommendations

Recommendation # 1: Fire Departments and city building departments should work together to ensure information on hazardous buildings is readily available to both.

Discussion: Abandoned buildings and occupied structures in deteriorated conditions can and do pose numerous hazards to fire fighters’ health and safety as well as the general public.7 Hazards should be identified and warning placards affixed to entrance doorways or other openings to warn fire fighters of the potential dangers. Such hazards can be structural as the result of building deterioration or damage from previous fires. Gutted interiors also increase the amount of exposed flammable materials and contain open pathways for rapid flame spread. Structural hazards can occur when building owners or salvage workers remove components of the building such as supporting walls, doors, railings, windows, electric wiring, utility pipes, etc. Abandoned materials such as wood, paper, and flammable or hazardous substances, as well as collapse hazards, constitute additional dangers fire fighters may encounter. Collapse hazards can include chimney tops, parapet walls, slate and tile roof shingles, metal and wood fire escapes, HVAC or other mechanical equipment, solar electrical collectors and cells, advertising signs, and entrance canopies.

Fire departments should work with city and local authorities to develop and implement a strategy to identify, mark, secure, and where possible demolish unsafe structures within their jurisdictions. The IAAI / USFA Abandoned Building Project, conducted by the International Association of Arson Investigators and the US Fire Administration, is one example of a program that can be utilized to aid and assist fire fighter safety and health by identifying, marking, and/or removing unsafe structures.7 The Abandoned Building Project Toolboxexternal icon can be found at the Web site: http://www.interfire.org/features/AbandonedBuildingProjectToolBox.asp.

In this incident, the fire department responded to a structure that had been cited by the city building department for a number of code violations including structural deterioration. This information was not available in the city dispatch system so it was not readily available to the fire department. The fire department did have a process to mark hazardous buildings identified by the fire department. The fire department had responded to a fire at an adjacent triple decker apartment building just a few months prior to this incident. The fire department had marked that structure as a hazardous structure (see Photo 8). The structure where the fatality occurred had been cited by the city building department for structural deficiencies but there was no formal process for the building department to notify the fire department of the deficiencies or to make this information readily available through the dispatch system. Information about structural deficiencies should be considered by fire officers when making operational decisions.

Photo 8. Hazardous building placard attached to exposure structure located just south of the fire building.

(NIOSH Photo)

Recommendation # 2: Authorities having jurisdiction should ensure that hazardous building information is part of the information contained in computerized automatic dispatch systems.

Discussion: Information related to building construction features and related hazards is valuable information for the fire fighter. Knowing the types of building construction and related hazards allows the fire department to develop effective standard operating procedures and guidelines and also allows responding crews to develop an effective incident action plan. Sources of information can include preplan inspections, code inspections, citation reports and first-hand experience from previous incidents. This type of information should be contained within the dispatch system so that when a fire is reported at a preplanned or otherwise identified location, the dispatcher can notify by radio all first responders with this critical information.8,9

It is vital that the fire department have immediate access to this type of information. Information can be transmitted via tele-type dispatch to each responding company at the time of the initial dispatch, via mobile data terminal in the fire apparatus, or verbally transmitted by the dispatcher with acknowledgement from the company officer that the information was received. In this incident, the structure where the fatality occurred had been cited by the city building department for structural deficiencies but there was no formal process for the building department to notify the fire department of the deficiencies or to make this information readily available through the dispatch system.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should train all firefighting personnel on the risks and hazards related to structural collapse.

Discussion: Proper training is an important aspect of safe fire ground operation. Both officers and fire fighters need to be aware of different types of building construction and their associated hazards.8, 10-11

The potential for collapse exists in any fire-damaged structure.12 Different phases of the fire suppression activities, such as the initial attack, offensive, defensive, and overhaul phases will have different hazards. For example, collapsing roof systems can exert pressure on supporting exterior walls, increasing the potential for wall collapse. Different roof systems may collapse at different rates. 11 While heavy timber roof systems will withstand more degradation by fire than lightweight engineered roof trusses, both types are subject to failure.13 One source of information related to structural collapse hazards is the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Engineering Laboratory, Fire Research Division. A DVD containing videos and reports related to structural collapse can be obtained from the NIST websiteexternal icon http://www.nist.gov/el/. 14 (Link Updated 8/16/2012)

Establishing priorities is another primary factor in safe fire ground operation that should be included in fire fighter training programs. The protection of life should be the highest goal of the fire service. According to retired Chief Vince Dunn, “When there is no clear danger to civilians, the first priority of firefighting should be the protection of fire fighters’ lives and when no other person’s life is in danger, the life of the fire fighter has a higher priority than fire containment or property consideration.”13 In this incident, a resident of the triple decker residential structure persisted in telling fire fighters that his friend was still inside the structure. This caused the Incident Commander to initiate a second interior search after declaring defensive operations and evacuating all fire fighters from the structure. This fire department had an abundance of experience fighting fires in triple decker structures and many fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH investigators commented on how they did not expect the building to collapse the way that it did. Fire fighters need to be aware that the potential of structural collapse is present at any structure fire. Fire fighters responded to a heavily involved structure fire and were on-scene in excess of 30 minutes at the time of the collapse. High winds accelerating the fire may have added to the structural degradation. Other factors that may have influenced the structural collapse included structural deterioration that was not readily apparent from the exterior, the off-set support beams, deteriorated foundation walls, additional weight added to the structure by the multiple hose lines in operation, and the sloping yard with water-saturated backfill.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should use risk management principles including occupant survivability profiling at all structure fires.

Discussion: While it is recognized that firefighting is an inherently hazardous occupation, established fire service risk management principles are based on the philosophy that greater risks will be assumed when there are lives to be saved and the level of acceptable risk to fire fighters is much lower when only property is at stake. Interior (inside a structure) offensive fire-fighting operations can increase the risk of traumatic injury and death to fire fighters from structural collapse, burns, and asphyxiation. Established risk management principles suggest that more caution should be exercised in abandoned, vacant, and unoccupied structures and in situations where there is no clear evidence indicating that people are trapped inside a structure and can be saved.15 More importantly, the fire department must establish a standardized method or approach to assess the risks encountered at each incident especially structure fires. Structure fires are very dynamic and fast paced operations with little room for error, mistakes, or miscalculations of the significance of the risk encountered.

The Incident Commander is specifically responsible for managing risk at the incident; however, one person cannot be expected to apply these principles to an incident if the organization has not integrated a standard approach to risk management into its standard operating procedures and its organizational culture. To be effective, risk management principles must be integrated into the entire operational approach of the fire department organization. They must be incorporated within the duties and responsibilities of every officer and member. The single most important reason to establish an effective incident management system is to ensure that operations are conducted safely. Every individual assigned to the incident is responsible for monitoring and evaluating risks and for keeping the Incident Commander informed of any factor that causes the system to become unbalanced. Continuous risk assessment should be reprocessed with every benchmark or task completed until the incident is ended.16

A standardized evaluation of the situation must occur at each incident starting with the first arriving officer or member of the department arriving on scene of the incident. This process starts with the scene size-up. This responsibility starts with the first arriving unit that must look at the entire incident scene versus focusing on a small part of the situation. During the size-up, the Incident Commander must remember the incident priorities which are:

- Life Safety

- Incident Stabilization

- Property Conservation

- Continuous – fire fighter safety

Situations where there is clear evidence or indication that there is a life safety (imminent rescue or trapped occupants) changes the focus of the strategy and incident action plan. Established risk management principles dictate that more caution is exercised in abandoned, vacant, and unoccupied structures.

In general terms, the risk management plan must consider the following: (1) risk nothing for what is already lost—choose defensive operations; (2) ex¬tend limited risk in a calculated way to pro¬tect savable property—consider offensive operations; (3) and extend very calculated risk to protect savable lives—consider of¬fensive operations.13, 15, 17 NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, Chapter 8.3 addresses the use of risk management principles at emergency operations. Chapter 8.3.4 states that risk management principles shall be routinely employed by supervisory personnel at all levels of the incident management system to define the limits of acceptable and unacceptable positions and functions for all members at the incident scene. Chapter 8.3.5 states that at significant incidents and special operations incidents, the Incident Commander shall assign an incident safety officer who has the expertise to evaluate hazards and provide direction with respect to the overall safety of personnel. The annex to Chapter 8.3.5 contains additional information.18

Search and rescue efforts must be based on the potential to save savable lives. According to retired Fire Chief Gary Morris, a safe and appropriate incident action plan can’t be accurately developed until determining if any occupants are trapped, where they are located, and can the occupants survive the fire conditions during the entire rescue operation. If occupant survival isn’t possible for the entire rescue period, the Incident Commander must evaluate conditions based upon the risk to fire fighters and revise the strategy and Incident Action Plan, taking a more cautious approach to fire ground operations. Fire control should be obtained before proceeding with the primary and secondary search efforts.19

A fire in a building today is not what it was 50 years ago. Yet, fireground tactics have not changed to be consistent with the effects of fire conditions in today’s modern furnishings. As a result of the increased use of plastics in our buildings, today’s fires are hotter and flashover occurs more quickly than in the past, releasing extreme levels of toxins. Fire models reflect that flashover can occur in less than five minutes and reach a temperature of more than 1,100°F. When exposed to fire, plastics burn hotter and produce highly toxic gases. For example, a pound of wood when burned produces 8,000 British thermal units (BTUs). On the other hand, a pound of plastic can produce 19,900 BTUs when burned. The human limit for temperature tenability is 212 degrees. On many occasions, flashover can occur as the first fire companies are arriving on the scene. In such circumstances, the survivability of any victims in the affected compartment can be very limited or nonexistent.20 Fire fighter fatality reports reflect what can happen without a thorough size-up that includes a survivability profile.19

The effects of carbon monoxide poisoning on a victim is well known to the fire service. Due to the increased use of plastics and synthetic materials, carbon monoxide is produced in very high concentrations and very quickly in structure fires. As a result, victims die sooner than in the past. What’s not as well known, but is evolving as a killer for both the victim and firefighters, is cyanide poisoning. Where carbon monoxide kills by blocking oxygen absorption in the blood, cyanide kills the body’s organs. Literature reflects that a low concentration of 135 PPM of cyanide and carbon monoxide will kill a person in 30 minutes. At 3,400 PPM, it can kill in less than one minute. It’s not uncommon for a fire in today’s buildings to routinely produce 3,400 PPM of cyanide. Where a victim may be resuscitated from the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning, the victim may not survive the organ damage caused by cyanide poisoning.20