A Volunteer Mutual Aid Captain and Fire Fighter Die in a Remodeled Residential Structure Fire - Texas

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2007-29 Date Released: November 3, 2008

SUMMARY

On August 3, 2007, a 19 year-old male fire fighter (victim #1) and a 42 year-old male Captain (victim #2) responding from the same volunteer mutual aid department were fatally injured during a residential structure fire. At 0136 hours, dispatch reported a residential structure fire. While enroute, the fire district’s Assistant Chief requested mutual aid from two neighboring departments due to dispatch updating the report to a fully involved structure fire. At 0150 hours, the Assistant Chief (Incident Commander) arrived on scene with four other fire fighters in an engine. At 0151 hours, the first interior attack crew entered the structure with flames visible in the foyer. At 0213 hours, the initial attack crew briefed a new interior attack crew (the victims) from the second mutual aid department on the location of a few hot spots to be knocked down and the presence of light smoke. At 0216 hours, the IC requested ventilation. Horizontal and vertical ventilation was conducted and a powered positive pressure ventilation fan was utilized at the front door but little smoke was pushed out. Minutes later, heavy dark smoke pushed out of the front door. The IC made several attempts to radio the interior attack crew with no response. Approximately 21 minutes after entry, an evacuation horn was sounded. A three member RIT team made entry and located one of the victims, but was unable to fully extricate him. Ultimately, several RIT teams were necessary to recover the victims. At 0237 hours, victim #1 was brought out. At 0248 hours, victim #2 was brought out. Both victims died of smoke inhalation and thermal injuries.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that fire fighters are equipped with a radio, trained on proper radio discipline, and trained on how to initiate emergency traffic when in distress

- ensure that the IC conducts a risk-versus-gain analysis prior to committing to interior operations and continues the assessment throughout the operations

- ensure that fireground accountability is established via an Incident Command System

- ensure that proper ventilation is done to improve interior conditions and is coordinated with the interior attack

- ensure that a Rapid Intervention Team is staged and ready to initiate rescue efforts, and that team members have been trained in RIT tactics

- ensure that periodic mutual aid training is conducted

INTRODUCTION

On August 3, 2007, a 19 year-old male fire fighter (victim #1) and a 42 year-old male Captain (victim #2) responding from the same mutual aid department were fatally injured during a residential structure fire. On August 27-31, 2007, an Engineer and an Occupational Safety and Health Specialist from the NIOSH, Division of Safety Research, Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program traveled to Texas to investigate the incident. Meetings were conducted with the fire chiefs from the initial responding and mutual aid departments and representatives from the State Fire Marshals’ Office. The NIOSH investigators conducted interviews with responding fire fighters and officers. The NIOSH investigators reviewed the fire department’s Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), the Fire Marshal’s report, the officers’and victim’s training records, photographs of the incident scene, written witness statements, dispatch transcriptions and the coroner’s report. The victims’ personal protective equipment (PPE) including self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and protective clothing were examined. The SCBAs were examined by NIOSH’s National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory to determine conformance to the NIOSH approved configuration. (see Appendix for report)

Fire Department

The volunteer district department had 1 station at the time of incident with a total of 14 members serving a population of 15,000 in a geographic area of approximately 31 square miles. The first volunteer mutual aid department (#1) had 2 stations with a total of 25 members serving a population of 10,000 in a geographic area of approximately 90 square miles.

The second volunteer mutual aid department (#2) (victims #1 & #2) had one station with a total of 24 volunteer fire fighters serving a population of over 20,000 residents in a geographic area of approximately 48 square miles.

The State of Texas requires that volunteer fire fighters complete a Basic Fire Suppression Curriculum. It is equivalent to the National Fire Protection Association’s (NFPA) Fire Fighter I, Fire Fighter II, HazMat-Awareness and HazMat-Operations. The above fire departments routinely held joint training for several years prior to the incident, but the training had not been held in recent years.

Training / Experience

Victim #2 was a Captain with 7 years of volunteer fire fighting experience. He had completed the Basic Fire Suppression training, Field Training, Developing Fireground Expertise, Fire Fighter Survival Training and various other administrative and technical courses.

Victim #1 was a fire fighter with 1 year of volunteer fire fighting experience. He had completed the Basic Fire Suppression training, Field Training, and various other administrative and technical courses.

The Incident Commander had 17 years of volunteer fire fighting experience and had completed the National Incident Management System training, Incident Scene, Construction Awareness, Risk Management, Developing Fireground Expertise, Leadership Skills and various other administrative and technical courses.

Personal Protective Equipment

At the time of the incident, each victim was wearing personal protective equipment consisting of turnout coat and pants, gloves, a helmet, hood, and SCBA with an integrated PASS device. Victim #2 carried a portable radio which had been in operation at the scene.

The two SCBA were heavily damaged by the fire. Victim #1’s SCBA was too severely damaged to be tested. Victim #2’s cylinder was damaged to the point where it could not be safely pressurized. Consequently, only two abbreviated tests could be conducted testing gas flow and the remaining service life indicator (low-air alarm) since these tests did not require the use of a cylinder. The SCBA passed both tests. The vibrating alarm on the service life indicator activated; however, the heads-up display did not function. Given the extensive damage to both units, it is not possible to determine if malfunctions of the SCBA may have contributed to the fatal incidents.

The PASS devices were physically examined, but no further testing was conducted. Victim #1’s PASS device could be activated but victim #2’s PASS device could not (see exhibit). Note: At least one PASS device was heard during the incident.

Apparatus and Personnel

On scene at 0150 hours:

- District Fire Department Engine #1 [E1] – Assistant Chief (Incident Commander (IC)/Driver) and four fire fighters

On scene at 0203 hours:

- Mutual Aid Fire Department #1 Engine #2 [E2] – Chief (driver) and two fire fighters

- Mutual Aid Fire Department #1 Engine #3 [E3] – Five fire fighters

- Mutual Aid Fire Department #1 Tanker #2 [T2] – Driver

On scene at 0209 hours:

- Mutual Aid Fire Department #2 Engine #4 [E4] – Chief (driver), Captain (victim#1), victim #2 and two other fire fighters

- Mutual Aid Fire Department #2 Engine #5 [E5] – Two fire fighters

- District Fire Department Tanker #1 [T1] – Driver

Building Information

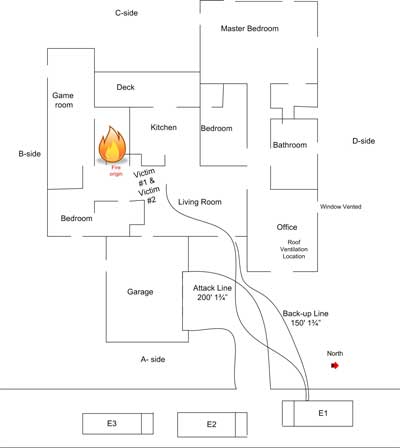

The 2,700 square foot building was a single story, non-sprinklered residential house that was constructed of wood framing with exterior wood sheathing. The roof consisted of wood rafters with plywood sheathing and conventional asphalt shingles. The structure had been remodeled with several additions over the years (See Diagram #1). The right side addition had been added using engineered joists covered with plywood as an attic floor with a stick built roof which was tied into the existing roof of the main structure (this section is where venting was performed with little effect due to the attic flooring). See photos #1 and #2.

|

|

Photo #1: Shows right side addition’s ceiling joists made of engineered joists covered with plywood. Vertical roof ventilation was done on the roof rafters above this ceiling.

|

Note: According to the fire marshal’s report, the exact cause of the fire could not be determined due to the extensive fire damage to the structure. The fire marshal’s report stated the fire originated in the laundry room and hallway area near the front bedroom. See Diagram #1

|

|

Photo #2: Front and right side view (A/D corner) of the fire structure showing roof pitch of right side addition. Roof ventilation was conducted above the front window about 10 feet back from the edge of the roof. |

INVESTIGATION

At 0136 hours, dispatch reported the fire. While enroute, the fire district’s Assistant Chief requested mutual aid from two neighboring departments due to dispatch updating the report to a fully involved structure fire. Also while enroute, the Assistant Chief, driving in E1 with 4 fire fighters on-board, assigned a two-man attack crew to be ready for entry. This left the Assistant Chief and a fire fighter as the backup or rapid intervention team and a pump operator. At 0150 hours, the Assistant Chief arrived first on scene with the 4 fire fighters and assumed Incident Command (IC). The attack crew immediately pulled a 200 foot crosslay of 1 ¾” hoseline. A fire fighter brought out the positive pressure ventilation (PPV) fan and laid a second 150 foot crosslay of 1 ¾” hoseline to the front of the structure. The IC noticed a civilian across the street and spoke with him. The civilian was the homeowner and informed the IC that everyone was out of the house. The IC relayed that information to the attack crew.

At 0151 hours, the E1 interior attack crew entered the structure with flames visible at the front door. The crew backed out of the structure after being inside for a few minutes due to the flames overhead near the door way. At 0156 hours, the positive pressure ventilation fan at the front door was started and the second hose line was charged. The IC discussed fire conditions with the attack crew who indicated that they could get it under control. The IC reminded them to maintain radio communications while inside. The first attack crew members switched positions on the nozzle then re-entered.

At 0159 hours, the IC requested that the utility company cut power and dispatch send emergency medical services (EMS). At 0203 hours, mutual aid department #1 responded with two engines and a tanker. The Chief (Chief #1) from the first mutual aid department was requested by the IC to organize a RIT team. At 0209 hours, mutual aid department #2 responded with two engines with a Chief (Chief #2), a Captain (victim #2) and five fire fighters (one of whom was victim #1). The district fire department T1 arrived on scene. Chief #2 requested assignment and was assigned to the rear (C-side).

At 0213 hours, the E1 interior attack crew backed out due to a low air alarm and briefed attack team #2 (victim #1 and #2) from the second mutual aid department. The briefing identified the location of a few hot spots to be knocked down and the presence of light smoke. Attack team #2 entered the structure with victim #1 on the nozzle.

At 0215 hours, Chief #2 walked around the structure counter-clockwise noticing smoke in all windows and smoke coming from the B/C and C/D corners of the structure. Victim #2 radioed the IC and asked if the power had been shut-off. Chief #2 asked the IC about vertical ventilation. At 0216 hours, the IC requested vertical ventilation. The IC requested an interior report from attack team #2 but received no response. At 0218 hours, the IC again requested a report from attack team #2 with no response. A crew was on the roof trying to vent the A/D corner, but they were having saw problems. Another saw was retrieved and the roof was vented releasing minimal smoke.

At 0226 hours, heavier and darker smoke began pushing out of the entire front door opening and overriding the PPV fan. Note: The PPV fan and vertical ventilation had little effect due to an attic floor being installed. At 0230 hours, Chief #2 had horizontally vented the window on the D-side near the A/D corner. At 0231 hours, the IC requested the RIT to be at the ready. The RIT team members were out of place and doing other tasks.

At 0234 hours, Chief #2 from the second mutual aid department asked the IC how long the crew had been inside the structure. The IC responded “too long”. Chief #2 ordered the pump operator on E1 to sound the evacuation horns – 3 air horn blasts. Heavy fire continued to roll out of the front door. A three member RIT team was re-organized and assembled near the front door. One of the members made entry and located both victims by following the hoseline and PASS device alarm. Victim #2, behind victim #1, was moved about four feet then became caught on something. The RIT member backed out, met the other two members making entry, and explained that victim #2 could not be fully extricated because he was stuck. The other two members located victim #1 and it took both of them pulling to dislodge the victim and get him near the front door. At 0236 hours, the IC ordered fire suppression to cease. At 0237 hours, the IC and two other fire fighters near the door pulled the RIT team out along with victim #1.

At 0238 hours, the IC ordered accountability. At 0244 hours, a second two member RIT team entered the structure following the hose line and located victim #2. Victim #2 was rolled over on his back, uncovering the nozzle that was flowing water. One member of the 2nd RIT became ill, and both members backed out. A third RIT team made entry, with one member staying near the door, and the other two members locating the victim. The two RIT team members struggled to get the victim to the door. At 0248 hours, the third member assisted with moving victim #2 outside. (See Diagram #1) Both victims received cardiopulmonary resuscitation and were transported to the hospital where they were pronounced dead.

Both victims were recovered with their facepieces on. Victim #2’s SCBA cylinder had an undetermined amount of air; victim #1’s cylinder was empty. It is undetermined why the two victims did not respond to the IC’s calls or exit the structure when their low air alarms went off. Victim #2’s low air alarm was found to be functional at the post-incident testing. Victim #1’s SCBA was damaged during the extrication, and it could not be determined if the low air alarm was functional prior to the incident.

|

|

Diagram 1. Shows Location of victims and hose lay at time of incident.

|

Cause of Death

The coroner listed the cause of death for both victims as smoke inhalation and thermal injuries. Soot was present in the airways. Victim #1’s heart blood carboxyhemoglobin saturation was 30%. Thermal injuries were present over approximately 10% of the body. Affected areas were chest, hands, and back. Victim #2’s heart blood carboxyhemoglobin saturation was 40%. Thermal injuries were present over approximately 30% of the body. Affected areas were head, chest, hands, arms, back and buttocks.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are equipped with a radio, trained on proper radio discipline, and trained on how to initiate emergency traffic when in distress

Discussion: All fire fighters on the fireground should be equipped with a radio. The radio is an essential tool for the fire fighter to communicate with incident command and team members. Fire fighters must receive training on the proper operation of portable radios in regards to their operation and the department’s standard operating procedures on the fireground, from reporting interior size-up/conditions to the IC, as well as, transmitting a distress signal. Radio discipline includes using standard protocol and terminology; using clear, concise text; talking slowly; and listening.1,2

It is vital that each fire fighter be equipped with a radio to inform command of interior conditions and special hazards, and in case of an emergency.2 Fire fighters must act promptly when they become lost, disoriented, injured, low on air, or trapped. They must transmit a distress signal for themselves or a partner while they still have the capability. A Mayday should be called using appropriate terminology, i.e. Mayday for a life-threatening situation such as a missing member or Urgent for a potentially serious problem that is not life-threatening.3, 4 Emergency traffic receives the highest communication priority from the IC, Dispatch, and all fireground personnel. All other radio traffic should stop when this emergency traffic is initiated to clear the channel and allow the message to be heard. The quicker the IC is notified and a RIT team is activated, the greater the chances are of a fire fighter being rescued and surviving. Once a distress signal is transmitted (or not) the distressed fire fighter can and should activate his PASS device and the emergency button on his radio to increase the chances of being located.

In this incident, only the captain (victim #2) had a radio. The victims had both been in the structure for approximately 21 minutes on their 30 minute bottles and had not been heard from for approximately 19 minutes. The IC attempted several times to contact the interior crew. It is unknown why the crew did not communicate with the radio, back out when their low air alarms went off, transmit a distress signal, activate the radio emergency button or activate their PASS devices.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that the IC conducts a risk-versus-gain analysis prior to committing to interior operations and continues the assessment throughout the operations

Discussion: Size-up includes assessing risk-versus-gain at the start and throughout the fire operations. Elements included in this analysis are: characteristics of the structure (e.g., type of construction, age, type of roof system, etc.), time considerations (i.e., time of day, amount of time fire was burning prior to fireground operations), contents of the structure, and potential hazards. The level of risk to the fire fighters must be balanced against the potential to save lives or property.1

This incident occurred in an unoccupied residential structure. It had been burning for approximately 20 minutes prior to arrival of the district fire department and had flames showing at the front door.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure that fireground accountability is established via an Incident Command System

Discussion: It is the responsibility of all officers to account for every fire fighter assigned to their company and to relay this information to the IC. A fire fighter should communicate with the supervising officer by portable radio to ensure accountability and indicate completion of assignments and duties. One of the most important aids for accountability at a fire is the Incident Command System (ICS). ICS is primarily a command and control system delineating job responsibilities and organizational structure for the purpose of managing operations for all types of emergency incidents. Fire fighter accountability is an important aspect of fire ground safety that can be compromised when teams are split up. Names on coats, reflective shields or company numbers on helmets, and helmet and turnout clothing colors are visual queues that fire fighters can use to maintain team continuity in poor visibility. Accountability on the fireground is crucial for fire fighter safety and may be accomplished by several methods. All fireground personnel are responsible to actively participate in the accountability system. 1, 2

As a fire escalates and additional fire companies respond, communication assists the IC with accounting for all fire fighter companies at the fire, at the staging area, and at rehabilitation. With an accountability system in place, the IC may readily identify the location and time of all fire fighters on the fireground.

In this incident, two mutual aid departments were working with the district fire department. The IC was provided assistance from the mutual aid Chiefs. However, not all ICS functions were established to account for monitoring the interior crew time in the structure and fireground personnel accountability until after the RIT team made entry. This situation resulted in not having accountability of all the fireground personnel, not adequately delineating job responsibilities (i.e., planning officer, safety officer, etc), and not having the organizational structure for the purpose of managing operations.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that proper ventilation is coordinated with interior attack

Discussion: Ventilation is performed to remove the products of combustion, allowing fire fighters to advance on the fire. When venting, the principle is to pull the fire, heat, smoke, and toxic gases away from victims, stairs, and other egress routes.5 Ventilation is necessary to improve a fire environment so that fire fighters can approach a fire with a hoseline for extinguishment. Only after a charged hoseline is in place ready for extinguishment is ventilation of windows and doors most effective. Command should determine if and where ventilation is needed. The type of ventilation should be determined, based on an evaluation of the structure and conditions on arrival. Decisions regarding ventilation should be communicated to all fire fighters on the scene. Chapter 11 of Essentials of Fire Fighting, 5th edition, states that, “ventilation must be closely coordinated with fire attack. When a ventilation opening is made in the upper portion of the building, a chimney effect (drawing air currents throughout the building in the direction of opening) occurs.” 6

In this incident, ventilation was being performed while the interior attack crew was already inside working. When the ventilation was completed, minimal smoke was pushed out of the vented hole but dark smoke pushed out of the front door, in spite of the fact that a PPV fan was set up at the front door. Note: The dark smoke pushing out the door indicated that the conditions were worsening and the vertical ventilation was not impacting the fire.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should ensure that a Rapid Intervention Team is staged and ready to initiate rescue efforts, and that team members have been trained in RIT tactics

Discussion: Fire departments should have a rapid intervention team (RIT) standing by during any structure fire to rescue a trapped, injured, or missing fire fighter. NFPA 1500, section 8.5.7 states that: “In the initial stages of an incident where only one crew is operating in the hazardous area at a working structure fire, a minimum of four individuals shall be required, consisting of two individuals working as a crew in the hazardous area and two individuals present outside this hazardous area available for assistance or rescue at emergency operations where entry into the danger area is required”. Further, NFPA 1500, section 8.8.7 states that: “At least one dedicated RIT shall be standing by with equipment to provide for the rescue of members that are performing special operations or for members that are in positions that present an immediate danger of injury in the event of equipment failure or collapse”. 2 In areas where response time is lengthy, a qualified RIT team should always be part of the initial alarm assignment. When the team is assigned as a RIT, they must be at the ready to initiate rescue when called upon. When standing by, the RIT team should monitor designated radio traffic and not assist in regular fire fighting activities.

Training is an important aspect of all fire fighters tactics. RIT tactics are unique and their use requires RIT-specific training. Continual RIT training is necessary to have a successful rapid intervention team.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should ensure periodic mutual aid training is conducted

Discussion: Mutual aid companies should train together and not wait until an incident occurs to attempt to integrate the participating departments into a functional team. The impact of differences in equipment and procedures need to be identified and resolved before an emergency where lives may be at stake. Procedures and protocols that are jointly developed, and have the support of the majority of participating departments, will greatly enhance overall safety and efficiency on the fireground. Once methods and procedures are agreed upon, training protocols must be developed and joint-training sessions conducted periodically to relay appropriate information to all affected department members. 7

REFERENCES

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1561: Standard on emergency services incident management system. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1500: Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Clark BA [2004]. Calling a maydayexternal icon: The drill. (http://www.firehouse.com/article/10515446/calling-a-mayday-the-drill). Date accessed: November 2008. (Link updated 10/4/2012)

- DiBernardo JP [2003]. A missing firefighter: Give the mayday. Firehouse, November issue.

- Klaene BJ, Sanders RE [2000]. Structural Fire Fighting. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association

- International Fire Service Training Association [2008]. Essentials of Fire Fighting and Fire Department Operations, 5th ed. Stillwater, Ok: Fire Protection Publications, Oklahoma State University.

- Sealy CL [2003]. Multi-company training: Part 1. Firehouse, February 2003 Issue.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Matt Bowyer, General Engineer and Steve Berardinelli, Occupational Safety and Health Specialist, with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Division of Safety Research at NIOSH. Eric Welsh, Engineering Technician, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, inspected SCBAs and conducted the performance tests, Vance Kochenderfer, NIOSH Quality Assurance Specialist, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, wrote the SCBA evaluation report. An expert technical review was conducted by Battalion Chief of Safety John J. Salka, Jr., New York City Fire Department.

exhibit

|

Status Investigation Report of Two

Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus

Submitted by the

Fire Department

Texas

NIOSH Task Number 15560

August 28, 2008

Disclaimer

| The purpose of Respirator Status Investigations is to determine the conformance of each respirator to the NIOSH approval requirements found in Title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 84. A number of performance tests are selected from the complete list of Part 84 requirements and each respirator is tested in its “as received” condition to determine its conformance to those performance requirements. Each respirator is also inspected to determine its conformance to the quality assurance documentation on file at NIOSH.

In order to gain additional information about its overall performance, each respirator may also be subjected to other recognized test parameters, such as National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) consensus standards. While the test results give an indication of the respirator’s conformance to the NFPA approval requirements, NIOSH does not actively correlate the test results from its NFPA test equipment with those of certification organizations which list NFPA-compliant products. Thus, the NFPA test results are provided for information purposes only. Selected tests are conducted only after it has been determined that each respirator is in a condition that is safe to be pressurized, handled, and tested. Respirators whose condition has deteriorated to the point where the health and safety of NIOSH personnel and/or property is at risk will not be tested. |

Investigator Information

The SCBA inspection and performance tests were conducted by Eric Welsh, Engineering Technician. This report was written by Vance Kochenderfer, Quality Assurance Specialist. Both investigators are part of the Technology Evaluation Branch, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, located in Bruceton, Pennsylvania.

Status Investigation Report of Two

Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus

Submitted By the

Fire Department

NIOSH Task Number 15560

Background

As part of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, the Technology Evaluation Branch agreed to examine and evaluate two, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

This SCBA status investigation was assigned NIOSH Task Number 15560. The Fire Department was advised that NIOSH would provide a written report of the inspections and any applicable test results.

The SCBA, sealed in corrugated cardboard boxes, were delivered to the NIOSH facility in Bruceton, Pennsylvania on August 31, 2007. After their arrival, the sealed packages were taken to the Firefighter SCBA Evaluation Lab (building 108) and stored under lock until the time of the evaluation.

SCBA Inspection

The packages were opened and a complete visual inspection of both units was conducted on April 2, 2008 by Eric Welsh, Engineering Technician, NPPTL. The SCBA were examined, component by component, in the condition as received to determine their conformance to the NIOSH-approved configuration. The visual inspection process was videotaped. The SCBA were identified as the Scott Air-Pak 2.2 model.

The complete SCBA inspection is summarized in Appendix I. The condition of each major component was also photographed with a digital camera. Images of the SCBA are contained in Appendix III.

Both SCBA have suffered heat and mechanical damage. The lens of the Unit #1 facepiece is bubbled from heat exposure, and the voice amplification unit and voicemitter are pulled away from the lens, compromising the seal. Its low-pressure hose has been severed along with the heads-up display wiring. The cylinder of Unit #1 has some scuffs and nicks near the dome end.

Unit #2’s facepiece lens is very dirty, and the frame holding the faceseal to the lens damaged. Some debris and feathers were found in the facepiece interior. There is molten material adhered to many parts of this SCBA, and heat damage to the heads-up display wiring, PASS control module housing, plastic cylinder retaining strap hardware, and fabric components of the harness. There is heat damage to the composite wrapping of the Unit #2 cylinder as well as the valve’s pressure gauge lens and rubber end bumper.

Personal Alert Safety System (PASS) Device

A Personal Alert Safety System (PASS) device was attached to each SCBA.; During the inspection, the PASS device of Unit #1 was activated and the alarm modes appeared to function correctly. However, it was not tested against the specific requirements of NFPA 1982, Standard on Personal Alert Safety Systems (PASS), 1998 Edition. The Unit #2 PASS device could not be activated. Because NIOSH does not certify PASS devices, no further testing or evaluations were conducted on the PASS unit.

SCBA Testing

The purpose of the testing was to determine the SCBA’s conformance to the approval performance requirements of Title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 84 (42 CFR 84). Unit #1 was too severely damaged to be tested, and the Unit #2 cylinder was damaged to the point where it could not be safely pressurized. Therefore, only tests which do not require the use of the cylinder were conducted.

The following performance tests were conducted on Unit #2:

NIOSH SCBA Certification Tests (in accordance with the performance requirements of 42 CFR 84):

- Gas Flow Test [§ 84.93]

- Remaining Service Life Indicator Test (low-air alarm) [§ 84.83(f)]

Testing was conducted on April 7, 2008. All testing was videotaped. The SCBA met the requirements of the tests performed. The heads-up display did not function at all during testing.

Appendix II contains the complete NIOSH test report for the SCBA. Table One summarizes the test results.

Summary and Conclusions

Two SCBA were submitted to NIOSH by the Fire Department for evaluation. The SCBA were delivered to NIOSH on August 31, 2007 and inspected on April 2, 2008. The units were identified as Scott Air-Pak 2.2, 2216 psi, 30-minute, SCBA (NIOSH approval number TC‑13F‑80). Unit #1 could not be tested, and the cylinder of Unit #2 was judged to be unsafe to pressurize for testing.

Unit #2 was subjected to an abbreviated series of two performance tests not requiring the use of the cylinder. Testing was conducted on April 7, 2008. The SCBA met the requirements of both tests. The heads-up display on Unit #2 was not functional. No maintenance or repair work was performed on the unit at any time.

In light of the information obtained during this investigation, NIOSH has proposed no further action at this time. Following inspection and testing, the SCBA were returned to the packages in which they were shipped to NIOSH and placed in storage pending return to the Fire Department.

If Unit #1 is to be placed back in service, the facepiece and low-pressure hose must be replaced and the SCBA repaired, tested, and inspected by a qualified service technician. The damage to the Unit #1 cylinder must be evaluated by a Department of Transportation-authorized retester to determine whether it can be returned to use. Because of the extent of the damage to Unit #2, it appears unlikely that it can be feasibly repaired and returned to service.

This page was last updated on 11/6/08.