Machine Operator Killed In Masonry Block Palletizing Machine

|

|

New Jersey FACE 01-NJ-092

On August 8, 2001, a 30-year-old machine operator was killed when his head was crushed in a masonry block-palletizing machine. The incident occurred at a plant that manufactured masonry (cement) block. The victim was a machine operator who oversaw the automated machinery that made the blocks and stacked the finished blocks on wooden pallets. The victim was working at the “cuber,” a machine that arranged the rectangular blocks into a pattern that allowed them to be evenly loaded onto a square wooden pallet. There were no witnesses to the incident. Apparently, the victim was reaching into the machine with a hooked metal rod to clear a jam when his head was caught between a moving machine arm and a large bolt on the machine. NJ FACE investigators recommend following these safety guidelines to prevent future incidents:

- Employers should develop, implement, and enforce a comprehensive safety program in the safe operation and maintenance of machinery.

- All machines should be shut down, de-energized, and locked out before performing any type of maintenance or repairs.

- Employers must ensure that machine guards are always kept in place.

- Employers should conduct a job hazard analysis of all work activities with the participation of the workers.

- Employers should become familiar with available resources on safety standards and safe work practices.

INTRODUCTION

On August 29, 2001, NJDHSS FACE personnel received a newspaper article on a machine-related fatality that occurred on August 8, 2001. A FACE investigator contacted the employer and arranged to conduct a site visit, which was done on September 12, 2001. During the visit, the investigator interviewed the plant manager, examined the incident site, and photographed the machine involved in the incident. Additional information was obtained from the OSHA Compliance Officer and medical examiner’s report.

The employer was a building materials manufacturing plant that had been in business at the site for two years. Built in 1989, the present owner had purchased the plant in 1999 and shared the site with a separate concrete company. The plant was unionized and employed 13 to 15 workers, including inmates on a work-release program from a local prison. New employees were trained on-the-job with an experienced person. Manufacturing was done from Monday to Friday during one extended 12-hour shift, and Saturday was set aside for plant maintenance. The plant produced about 40,000 masonry blocks per week.

The victim was a 30-year-old male machine operator who had worked for the company since November, 2000. Described by the plant manager as a dependable worker, the victim worked many hours and was responsible for running the Saturday maintenance crew. He was a volunteer with the local fire department and was soon to be married.

INVESTIGATION

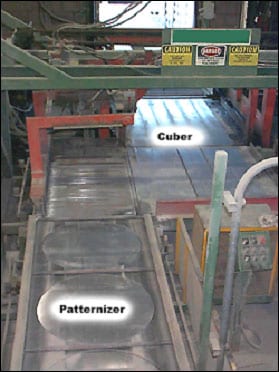

The site of the incident was the building material manufacturing plant located in a rural area. The plant was built in 1989 with a state-of-the-art automated process for manufacturing masonry block. In this process, aggregate and concrete were conveyed to a hopper where they were weighted and dumped into a batch mixer. The concrete mix was poured into molds and the molds transported into a kiln for curing. The blocks were removed from the molds and conveyed to patternizer and cuber, two interconnected machines that arranged the blocks into a pattern that allowed them to be neatly stacked on a wooden pallet. The pallets were then transported for storage outside the plant. The process was highly automated, requiring only a few employees to be on site to watch and maintain the machines.

The incident occurred on Wednesday, August 8, 2001, at 10:03 in the morning. The victim started his shift overseeing the machines in the block-making room. After being released from the molds, the newly-made blocks were conveyed to the patternizer. This was a series of turntables that rotated the blocks, allowing them to form an interlocking pattern when pushed together. The arranged blocks were then directed into a cuber, which gripped the tier of blocks and stacked them onto a pallet.

Photo 1. Block patternizing/cubing machine.

A second employee was working nearby in the same room, but their duties and the noise from the process left the two men to work mostly on their own. There were no witnesses to the incident. At about 10:00 a.m., the victim went to clear a jam in the cuber. He apparently stood on a frame member and leaned into the cuber to re-arrange the blocks with a hooked metal rod. As the machine cycled, the victim’s head became caught between the moving arm and a large stationary bolt securing a frame member. The coworker heard the victim yell and looked over to see him fall by the side of the machine. He went to help the victim, who had severe head injuries. Plant personnel called 911 for the police and EMS, who arrived within six minutes to find the victim unresponsive. The Medical Examiner’s office was notified, and the victim was pronounced dead of his injuries at the scene at 11:35 a.m.

|

|

| Photo 2. Cubing machine showing stationary bolt. | Photo 3. Fenced-in machine guard around machines. |

The Federal OSHA investigation noted that employees were trained to shut down the machine before attempting to rearrange the blocks with the hook. OSHA also noted that the machine was equipped with a freestanding fence to guard the machine, and that the fence may not have been properly positioned at the time of the incident. The Medical Examiner’s investigation report noted that the frame edge where the victim apparently stood on the machine was worn, as if it was stood on frequently. The M.E. investigator reported that a coworker confirmed this to be true. The plant manager reported that since the incident the fence had been permanently secured to the floor and that interlock devices had been ordered that would shut down the machine when a worker opened the fence entrance to the area.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1: Employers should develop, implement, and enforce a comprehensive safety program in the safe operation and maintenance of machinery.

Discussion: In this case, the victim leaned into the operating machine in an apparent effort to unjam it. It is recommended that a written safety program be developed that includes a plan for training supervisors and workers in the safe operation of the machines before they are allowed to use or maintain the equipment. Training should include standard operating procedures and safety practices for each piece of equipment. Close supervision and periodic retraining should be required to ensure that the worker knows how to operate the machine and is knowledgeable in company safety procedures. It was noted during the FACE investigation that the company was developing a safety program.

Recommendation #2: All machines should be shut down, de-energized, and locked out before performing any type of maintenance or repairs.

Discussion: The company did not have an effective lockout/tagout program at the plant at the time of the incident. Such a program would require employees to shut down and lock out the power supplies to any machines before maintenance or repairs are done. An effective program would include thorough employee training in lockout/tagout procedures and strict enforcement of the program. A lockout/tagout program may be required under the Federal OSHA Standard 29 CFR 1910.147.

Recommendation #3: Employers must ensure that machine guards are properly installed.

Discussion: The machine was guarded by a fence with an interlocked gate to prevent personnel from getting close to the operating machine. OSHA reports that this fence was not properly installed at the time of the incident. It is extremely important that all machine guards are kept in place at all times and that safety interlocks are in operating order. The company has permanently installed the fence and interlock after the incident.

Recommendation #4: Employers should conduct a job hazard analysis of all work activities with the participation of the workers.

Discussion: NJ FACE recommends that employers conduct a job hazard analysis of all work areas and job tasks with the employees. A job hazard analysis should begin by reviewing the work activities that the employee is responsible for and the equipment that is needed. Each task is further examined for fall, electrical, or other hazards the worker may encounter. The results of the analysis can be used to design or modify a written employee job description. If employers are unable to do a proper analysis, they should consider hiring a safety consultant to complete it.

Recommendation #5: Employers should become familiar with available resources on safety standards and safe work practices.

Discussion: It is extremely important that employers obtain accurate information on safety and applicable OSHA standards. The following sources of information may be helpful:

U.S. Department of Labor, OSHA

Federal OSHA will provide information on safety and health standards on request. OSHA has several offices in New Jersey that cover the following counties:

Hunterdon, Middlesex, Somerset, Union, and Warren counties………………………(732) 750-3270

Essex, Hudson, Morris, and Sussex counties……………………………………………..(973) 263-1003

Bergen and Passaic counties…………………………………………………………………(201) 288-1700

Atlantic, Burlington, Cape May, Camden, Cumberland, Gloucester,

Mercer, Monmouth, Ocean, and Salem counties…………………………………………(856) 757-5181

NJ Public Employees Occupational Safety and Health (PEOSH) Program

The PEOSH Act covers all NJ state, county, and municipal employees. Two state departments administer the Act; the NJ Department of Labor (NJDOL) which investigates safety hazards, and the NJ Department of Health and Senior Services (NJDHSS) which investigates health hazards. PEOSH has information that may also benefit private employers. Their telephone numbers are:

NJDOL, Office of Public Employees Safety ………………………………………(609) 633-3896

NJDHSS, Public Employees Occupational Safety & Health Program……………….(609) 984-1863

NJDOL Occupational Safety and Health On-Site Consultation Program

Located in the NJ Department of Labor, this program provides free advice to private businesses on improving safety and health in the workplace and complying with OSHA standards. For information on how to get a safety consultation, call (609) 292-3923.

New Jersey State Safety Council

The NJ State Safety Council provides a variety of courses on work-related safety. There is a charge for the seminars. Their telephone number is: (908) 272-7712.

Internet Resources

Other useful Internet sites for occupational safety and health information:

www.cdc.gov/niosh – The CDC/NIOSH website.

www.dol.gov/elaws/external icon -USDOL Employment Laws Assistance for Workers and Small Businesses.

www.nsc.org/Pages/Home.aspxexternal icon – National Safety Council (Link updated 4/1/2013)

www.state.nj.us/health/eoh/survweb/face.htmexternal icon – NJDHSS FACE Reports

REFERENCES

- Job Hazard Analysis. US Department of Labor Publication # OSHA-3071, 1998 (revised). USDOL, OSHA/OICA Publications, PO Box 37535, Washington DC 20013-7535.

ATTACHMENTS

- Job Hazard Analysis. US Department of Labor Publication # OSHA-3071, 1998 (revised). USDOL, OSHA/OICA Publications, PO Box 37535, Washington DC 20013-7535.

Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation (FACE) Project

Investigation # 01-NJ-092-01

Staff members of the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, Occupational Health Service, perform FACE investigations when there is a report of a targeted work-related fatal injury. The goal of FACE is to prevent fatal work injuries by studying the work environment, the worker, the task and tools the worker was using, the energy exchange resulting in fatal injury, and the role of management in controlling how these factors interact. FACE investigators evaluate information from multiple sources that may include interviews of employers, workers, and other investigators; examination of the fatality site and related equipment; and review of records such as OSHA, police, and medical examiner reports, and employer safety procedures, and training plans. The FACE program does not seek to determine fault or place blame on companies or individual workers. Findings are summarized in narrative investigation reports that include recommendations for preventing similar events. All names and other identifiers are removed from FACE reports and other data to protect the confidentiality of those who participate in the program.

NIOSH funded state-based FACE Programs include: Alaska, California, Iowa, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

To contact New Jersey State FACE program personnel regarding State-based FACE reports, please use information listed on the Contact Sheet on the NIOSH FACE web site. Please contact In-house FACE program personnel regarding In-house FACE reports and to gain assistance when State-FACE program personnel cannot be reached.

|

|

NJ Department of Health & Senior Services |

|

Back to New Jersey FACE reports

Back to NIOSH FACE Web