Construction Worker Killed When Cement Forms Fell from Crane

SUMMARY

|

| Photo 1 — Hammerhead crane at site. |

In February 2002, a 39-year-old construction worker was killed when he was struck by a load of cement forms that fell from an overhead crane. The man was part of a crew erecting a new building for a private college. A stationary hammerhead-type crane was being used to move 13 plywood and steel cement forms to a storage area outside the new building. The stack of forms weighed about 880 lbs (400 kg). The load was secured in a conventional fashion, with a two-leg wire rope bridle attached to two nylon slings, which were choked around the load. The load was level, and was raised without problems, however, in the middle of the swing, one sling end slipped or twisted out of the hook, and the entire load of forms fell about 30 feet (10 m) to a work area underneath. The victim was walking in this adjacent area and was struck by the falling load, which caused fatal head and neck injuries. The man who rigged the load, as well as the crane operator, were experienced workers, and did not notice anything unusual prior to or during the lift. The area from which the forms were lifted was out-of-sight from the crane operator, and the rigging man used a radio for communication. Initial investigation of the equipment (hooks, latches, slings, etc.) did not provide clues as to what caused the load to fall.

RECOMMENDATIONS based on our investigation are as follows:

- Communication and other workplace arrangements must be in place to prevent carrying suspended loads over workers and bystanders.

- Employers should provide training to all workers and crane operators regarding crane safety.

- Construction workers rigging loads for cranes should carefully check every load prior to signaling crane operators to lift the load, giving special attention to the condition of the safety latch on the hook.

- Construction materials should be stored in locations that minimize crane traffic over work areas.

- All workers should develop good habits of working defensively while on-the-job.

INTRODUCTION

In February 2002, a 39-year-old construction worker in Iowa was killed when cement forms fell on him from an overhead crane. The Iowa FACE program was alerted from local news sources, and began an investigation. Additional information was gathered from the medical examiner, and from the company safety manager, and a site visit was conducted a few weeks later by two FACE investigators. The FACE investigators met with the site superintendent and company safety officer, and photographs were taken of the work site, the overhead crane, and similar rigging items, identical to those used on the day of the fatal incident.

The employer is a commercial contractor with about 135 employees, 14 of which were working on site at the private college. The company had been in business for over 30 years, and was well known in the area, working year-around on several projects. The crew had worked together for several years, and had been working on that particular job since the previous summer. The victim had worked for this company for 10 years, and specialized as a concrete carpenter, frequently working with various cement forms, re-bars, etc. The company had an extensive written safety program, including training on rigging of loads, crane use, etc. They had monthly safety meetings, toolbox talks, and all crane operators had received intensive specialized training on crane setup, inspection, and operation. This was the company’s first fatality.

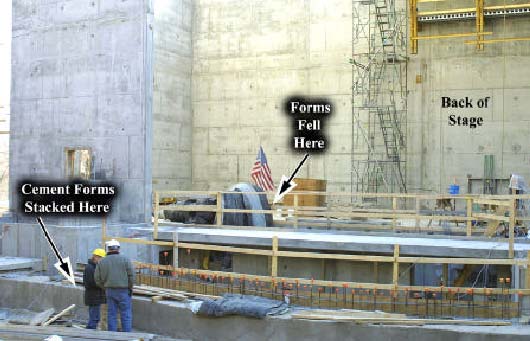

Photo 2 — View from inside auditorium showing area where cement forms were stacked, and where they fell.

INVESTIGATION

The construction crew was building a new auditorium for a private college, and had been pouring multiple concrete foundations and walls. The victim was working that day as the ground man, supplying other co-workers on a platform in the stage area of the auditorium (see Photo 2). There was no special reason he had to be in the area where the load fell, and exactly what he was doing at that time is unknown.

Each group of workers on site had a 2-way radio that provided communication with the crane operator. Each man with a radio could hear when a pick was being made, and could, if needed, direct the crane operator during a blind pick. The victim was wearing one of these radios when the accident occurred.

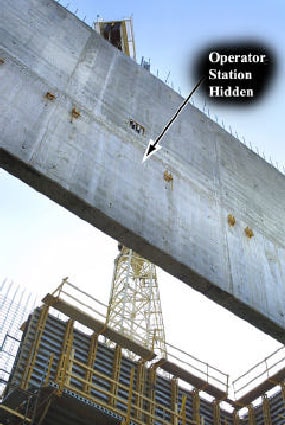

The electric powered hammerhead crane was erected near the southwest corner of the building, and provided full access to all areas under construction. This crane was 120 feet tall (36 m), with a reach of 180 feet (55 m), and a capacity of six tons (5.5 metric tons) at full extension. On a busy day, the crane was in constant use, making a lift about every 10 minutes, transporting all types of building materials — brick, mortar, lumber, re-bar, steel, etc. On the day of our visit, the crane was not in operation due to high winds. The operator routinely measures wind speed from his station, and will shut down the crane if the wind speed exceeds 30 mph (50 kmh). The crane was also equipped with an overload buzzer and automatic lockout if the load was excessive.

Photo 3 — Typical plywood and steel cement form.

The cement forms were of various sizes, and consisted of plywood sheets attached to a steel frame (see Photo 3). Most of them were 24 inches (60 cm) wide, and four, six, or eight feet (1.2, 1.8 or 2.4 m) long. These forms were used for interior walls, and not for exterior load-bearing walls. They were stacked inside the auditorium, out-of-sight from the crane operator’s station, due to an auditorium wall, which had previously been built (see Photo 6). The forms were stacked flat, with the two nylon slings arranged at appropriate locations to ensure a balanced load. On end view, the stack of forms was approximately 24 inches (60 cm) wide and 33 inches (84 cm) tall. The heavy-duty two-ply slings were four inches (10 cm) wide and 16 feet (4.8 m) long, with a choker capacity of 8,600 lbs. (3,900 kg) each. The slings were fairly new, being in service only a few weeks.

|

|

| Photo 4 — View of two nylon slings in typical choker position. | Photo 5 — Close-up of hook and sling end. |

Rigging consisted of a 1½-inch (3.8 cm) master link attached to a two-leg wire rope bridle, which was made of two, ¾-inch (19 mm) wire ropes, 10 feet long (3 m), attached to 10-inch (25 mm) eye hooks (see Photos 4, 5). Each eye hook had a five-ton capacity and a safety latch, which was functional on both hooks. The nylon web slings had eyes at both ends, and were configured in a choker hitch around the load of forms, with the free end slipped over each hook. Two workers rigged the slings, hooked the sling ends on the hooks, and one worker radioed for the operator to begin his lift. The load was level, and nothing unusual was noticed at this time, but apparently one of the sling ends was not fully seated within the hook.

The crane operator raised the load about 30 feet (10 m), then trolleyed in a bit, and began a swing to his right, to a storage location outside the building. In the middle of this swing, about 30 seconds after the lift began, one of the nylon sling eyes slipped out of the hook, and the load of forms momentarily shifted, then fell to a concrete work surface below. The victim was walking through the area under the load, and was struck on the head by the falling forms. Other workers rushed to his aid, but his injuries were severe, and he died at the scene.

After the incident, the eye hooks, the wire rope bridle legs, and the nylon slings, were inspected, but nothing unusual was found; therefore, the company soon put the equipment back in service. During our investigation, we examined hooks on one of the bridle legs. The safety catches were functional, but had considerable side-to-side play in the hinge. It appeared that if the end of a loop was not fully seated in the hook, the loop end could possibly twist or roll out, pushing the safety catch far to one side, leaving the hook open. Company representatives offered this as one possible reason that the sling failed.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The cause of death taken from the medical examiners report was, “craniocerebral trauma and thoracic / abdominal trauma.” An autopsy was performed which confirmed these findings.

Photo 6 — View of crane from location where cement forms were loaded.

RECOMMENDATIONS / DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1 Communication and other workplace arrangements must be in place to prevent carrying suspended loads over workers and bystanders.

Discussion: Large construction sites frequently have multiple crews working simultaneously in different locations, and crane traffic can be constant, as materials are moving overhead to various parts of the worksite. It is not practical, or safe, for workers to constantly look overhead to avoid walking or working under crane loads. Other means must be in place to avoid moving loads over workers as required by 29 CFR 1926.550 (a)(19). On some jobsites it is advisable to have a full-time worker monitor crane traffic, keeping workers and pedestrians away from suspended loads. In this case, the victim was not in his normal work area at the time of the incident, and it remains unclear what he was doing when the load fell.

Communication between the crane operator, the person rigging the load, and others at the jobsite must be effective. Crane operators must be aware of all work locations, and likewise, workers should be alerted to stay clear of areas where loads will be moving overhead. The concrete wall (in Picture 6) blocked the crane operator’s view to the location where the load was rigged. Even though they had radio contact, lack of visual contact may have compromised communication between the crane operator and the person rigging the load.

Depending on the situation, multiple people at a worksite may need to be involved in communicating where crane traffic will be, and how best to protect workers from the hazards of suspended loads. Effective radio and visual communication between foremen, crane operators, rigging persons, and possibly others at the jobsite, may be needed to avoid hazardous situations. Applicable ANSI hand signals should be used, and illustrations should be posted at the job site (29 CFR 1926.550(4)).

Recommendation #2 Employers should provide training to all workers and crane operators regarding crane safety.

Discussion: Safe crane operation requires regular maintenance, inspections, and proper use, as stated in 29 CFR 1926.550 Furthermore, specific layout of work areas and work practices at each worksite must be well understood by supervisors, workers, and crane operator(s). Regular training and supervision should address how materials are safely transported overhead, minimizing the risk of falling loads to workers or bystanders. Crane operators must be qualified, and riggers must also be trained in proper hand signaling and communicating with crane operators.

On taller buildings, communication is especially important, as it becomes increasingly difficult for workers and crane operators to judge safe or dangerous areas on the ground. As loads rise higher, the hazardous ground area underneath grows proportionally. In addition, if a load drops from a significant height, other factors must be considered: wind speed, swing direction, swing speed, and type / density of load.

Photo 7 — Close-up of a typical spring-loaded latch on a hook.

Recommendation #3 Construction workers rigging loads for cranes should carefully check every load prior to signaling crane operators to lift the load, giving special attention to the condition of the safety latch on the hook.

Discussion: In this case, the load fell after one of the slings came off the hook, but it is unclear how this occurred. Construction company representatives said it appeared to be a correctly attached and balanced load, however, for failure to occur, the sling had to come out of the hook. It is possible the nylon sling partially rolled or twisted out of the hook before the lift was begun, without the rigger noticing it.

The sling may not have been fully seated within the hook, the latch may have been partially open, or the latch may have been bent sufficient to be nonfunctional.

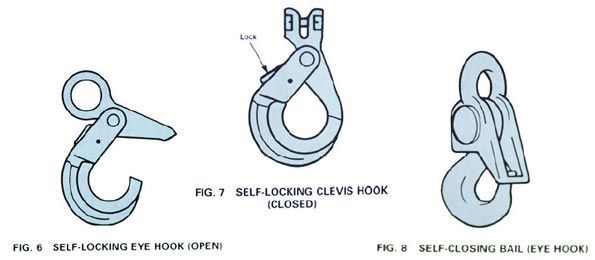

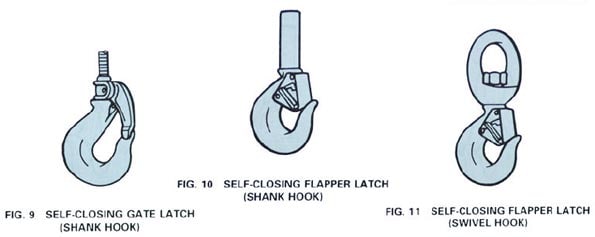

It is critical that a lifting hook has a functioning safety latch. Hooks without latches, or ones with damaged latches are sometimes called “killer hooks” for obvious reasons. Simple hook latches (see Photo 7) are easily damaged during normal use, and may bend to one side or the other compromising their function. Over the years, many new types of hooks have been invented, some with integral selflocking latches. These hooks offer significant protection from latch failure, and would be an excellent option for use in areas of high crane traffic (see appendix). During our investigation we were not able to inspect the actual hook used at the time of the fatal accident.

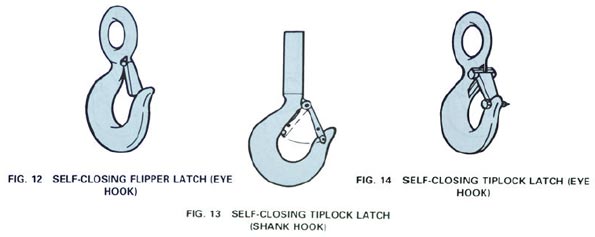

In this case the load appeared level, and the lift began normally, however, a second careful visual check may have been needed. The rigging failed during the swing to a storage area outside the building, out-of-sight from the worker who rigged the load. It may be possible that during the swing the load shifted and allowed one side of the sling to have less or no weight on it, allowing the sling to roll out of the hook. Although the mechanism of the failure is not known, it is necessary that all rigging be double-checked prior to signaling or radioing for the lift to begin. Since this incident, the company now uses a self-closing tiplock latch (see Fig. 13 in Appendix) for choker loads, instead of flipper latches (Fig. 12). The tiplock latch requires manual insertion of a locking pin, which confirms the sling end is properly seated in the hook.

Recommendation #4 Construction materials should be stored in locations that minimize crane traffic over work areas.

Discussion: Careful selection and organization of staging areas for delivery and loading of construction materials can minimize overhead hazards to workers. In many situations, space is limited, and contractors use any free space they can find for staging or storage of building materials. Accessibility, steep terrain, and utility right-of-way are just a few factors that supervisors must deal with, however, in many instances material storage areas can be arranged so that crane traffic over work areas is minimized. It would be beneficial to have a clear view from the tower crane operator’s station to storage areas. Good housekeeping is also essential in keeping storage areas accessible and free of hazards.

Recommendation #5 All workers should develop good habits of working defensively while on-the-job.

Discussion: Defensive driving is a well-known safety skill that has been widely adopted to prevent motor vehicle injury. This defensive driving philosophy is directly applicable to working on large construction sites, which are also inherently dangerous. Workers should be alert at all times for anything that could possibly go wrong, for sooner or later, this good habit will pay off. While it is not practical for workers to continually be looking overhead for crane hazards, likewise, it is not wise to ignore this risk entirely. In this case, it appears the victim was not performing a work-related task when the load fell, however, there was no information to indicate that he was careless.

References:

- 29 CFR 1926.550 Subpart N-Cranes, Derricks, Hoists, Elevators, and Conveyors.

- ASME (American Society of Mechanical Engineers) B30.10-1999, American National Standard, Hooks. (Hook images from same publication)

Appendix — Types of safety hooks. ( Reprinted from ASME B30.10-1999 by permission of The Society of Mechanical Engineers. All Rights reserved.)

|

|

|

Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation

FACE

FACE is an occupational fatality investigation and surveillance program of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In the state of Iowa, The University of Iowa, in conjunction with the Iowa Department of Public Health carries out the FACE program. The NIOSH head office in Morgantown, West Virginia, carries out an intramural FACE program and funds state-based programs in Alaska, California, Iowa, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

The purpose of FACE is to identify all occupational fatalities in the participating states, conduct in depth investigations on specific types of fatalities, and make recommendations regarding prevention. NIOSH collects this information nationally and publishes reports and Alerts, which are disseminated widely to the involved industries. NIOSH FACE publications are available from the NIOSH Distribution Center (1-800-35NIOSH).

Iowa FACE publishes case reports, one page Warnings, and articles in trade journals. Most of this information is posted on our web site listed below. Copies of the reports and Warnings are available by contacting our offices in Iowa City, IA.

The Iowa FACE team consists of the following: Craig Zwerling, MD, PhD, MPH, Principal Investigator; Wayne Johnson, MD, Chief Investigator; John Lundell, MA, Coordinator; Risto Rautiainen, PhD, M.Sc.Agr, Co-Investigator; Martin L. Jones, PhD, CIH, CSP, Co-Investigator.

To contact Iowa State FACE program personnel regarding State-based FACE reports, please use information listed on the Contact Sheet on the NIOSH FACE web site Please contact In-house FACE program personnel regarding In-house FACE reports and to gain assistance when State-FACE program personnel cannot be reached.

Back to NIOSH FACE Web