Assistant Manager at Ice Rink Asphyxiated by an Oxygen-Deficient Atmosphere - Alaska

FACE 9113

SUMMARY

An assistant ice rink manager (the victim) died of asphyxiation when he attempted to stop a refrigeration system gas (chlorodifluoromethane 22 or CFC-22) leak inside the compressor room at a mall complex. The refrigeration system had been leaking for an extended period of time when the victim, a maintenance supervisor, and a maintenance worker entered the compressor room through self-closing doors. All three individuals became unconscious and collapsed. The maintenance worker and supervisor were rescued and resuscitated by emergency rescue personnel. Since the victim was not in plain sight and rescue personnel were unaware of his presence, the victim was not immediately removed from the room. After being informed by a witness that a third person was in the room, rescue personnel reentered the room and extracted the victim. He could not be resuscitated. The victim was transported to a local hospital where he was pronounced dead on arrival by the attending physician. The victim and the maintenance supervisor wore air-purifying respirators, however, this type of respirator was inappropriate for the oxygen-deficient atmosphere. During the rescue, an emergency medical technician entered the room without wearing any respiratory protection.

NIOSH personnel concluded that in order to prevent future similar occurrences, employers should:

- ensure that workers are adequately protected from recognized hazards by installing appropriate engineering controls

- develop and implement a maintenance program that will address routine inspection and repair of refrigeration systems

- develop and implement a safety program designed to help workers recognize, understand, and control hazards

- ensure that workers are adequately protected from recognized hazards with appropriate personal protective equipment

- develop and implement a comprehensive emergency action plan.

In addition, fire departments and emergency rescue services should:

- establish a registry identifying potentially hazardous facilities, and inform emergency rescue personnel of these potential hazards, and of appropriate rescue methods and equipment

- ensure that responding personnel are properly trained in the selection and use of respiratory protective equipment.

INTRODUCTION

On May 20, 1991, a 24-year-old male assistant manager for a shopping mall ice skating rink was asphyxiated inside a compressor room while attempting to shut off a refrigerant gas (chlorodifluoromethane 22 or CFC-22) leak. The same day, officials of the Alaska State Department of Health and Social Services notified the Division of Safety Research (DSR) of the fatality, and the Alaska State Department of Labor (AKDOL) subsequently requested technical assistance. On May 20, 1991, two DSR researchers traveled to the incident site and began an investigation. On May 28, 1991, a research industrial hygienist from DSR traveled to the incident site to assist in the investigation. The DSR investigators reviewed the incident with the company owner, the AKDOL compliance officer, the city emergency medical technicians and firefighters who responded to the incident, and officials from the city health department. Photographs of the incident site were obtained during the investigation.

The employer was the owner of a 170-store indoor shopping mall which included a swimming pool and an ice skating rink. The owner, who had been in business for 12 years, had 24 employees, including 20 maintenance workers. The company did not have a safety policy, safety program or established safe work procedures. However, the company facility manager conducted monthly safety meetings which all employees were required to attend. The meetings consisted of a discussion of on-the-job safety issues. Employees did not receive any formal safety training.

INVESTIGATION

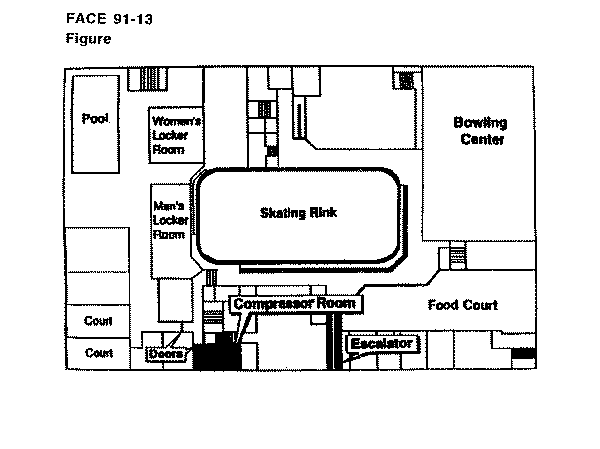

The incident site was a refrigeration system compressor room that served an ice skating rink located within a mall complex. The compressor room measured approximately 25 feet long by 20 feet wide by 10 feet high; it was accessible through two self- closing steel doors (one double door, and one single door) located at opposite ends of the room. The compressor room was 4 feet below the ground-level floor of the shopping mall. The refrigeration system installed there had a maximum capacity of 4,000 pounds of CFC-22 refrigerant. CFC-22 is a gas approximately three times more dense than air, with a relatively high vapor pressure at room temperature.

The ice skating rink refrigeration system had a history of refrigeration leaks documented for the 30 months preceding this incident. The ice skating rink manager stated that 2 months before the incident, the victim had reported several slow leaks of CFC-22 during routine equipment checks. One month before the incident, the ice skating rink manager wrote a letter to the maintenance manager requesting maintenance to repair them.

Nine days before the incident, a refrigeration mechanic who had been hired to charge the refrigeration system with CFC-22 and refrigerant oil also noticed CFC-22 leaks at the filter flange pipe and notified the maintenance manager. The maintenance manager directed the refrigeration mechanic to recharge the refrigeration system without repairing the leaks. The victim also told several non-supervisory employees about the problem, but nothing was done to correct it.

There were no eyewitnesses to several contributory events preceding the incident; however, evidence, calculations, and investigative examination suggest the following sequence of events (Figure).

Sometime during the 2 days before the incident, someone had attempted to stop a pinhole-sized leak in the filter flange pipe by tightening the pipe with a wrench. This caused a section of pipe to break off, and produced a much larger leak. Someone then plugged this leak by driving a makeshift plastic plug into the flange hole and sealing it with a putty-like material.

About 8:00 a.m. on the day of the incident, a shopping mall maintenance worker (maintenance worker #1) performing routine maintenance checks, observed refrigerant oil “oozing” from under the doors to the compressor room. He could not open the locked doors, but he heard a “hissing sound.” Looking through a crack between the two doors, he saw the lower part of the compressor room engulfed in a “freon mist,” 4 feet deep. Maintenance worker #1 left the area and phoned the maintenance supervisor to report the problem.

About 8:30 a.m., the maintenance supervisor entered the compressor room wearing an organic vapor cartridge gas mask. He attempted to isolate the leak but became disoriented. He de- energized the refrigeration system at the circuit panel and exited the compressor room. However, since the refrigerant was still under pressure, it continued filling the room. The maintenance supervisor complained to the ice skating director that his chest hurt, and that his heart was racing. The maintenance supervisor phoned the maintenance manager, and told him about the refrigerant leak. By this time approximately 685 pounds of CFC-22 refrigerant had leaked out of the refrigeration system (based on an estimate by a local mechanical engineer).

The skating director phoned the assistant ice rink manager (the victim) at his home, and asked him to come to work to help fix the problem in the compressor room. The victim arrived at the ice rink at about 8:40 a.m., and discussed the situation with the maintenance supervisor and another maintenance worker (maintenance worker #2). Using a key, the victim, maintenance supervisor, and maintenance worker #2 entered the compressor room. The victim was carrying tools and wearing a cartridge- type respirator. This type of respirator provides inadequate protection in an oxygen-deficient atmosphere. The self-closing doors to the compressor room closed and automatically locked behind them to bar entry to, but allow exit from, the room.

By about 8:50 a.m., some of the leaking CFC-22 had flowed from the compressor room into an adjoining health club pool area where two male patrons were swimming. Both patrons found it difficult to breath, and had to be rescued from the pool by two club workers. They were both taken outside where they subsequently recovered.

About 8:56 a.m., after hearing a noise “like a bang or a pop,” the ice skating director unlocked and opened the compressor room door. She saw the maintenance supervisor and maintenance worker #2 lying on the floor at the foot of the stairs, but did not see the victim, whom she knew was present. The victim was hidden to her view on the floor behind some refrigeration piping. The ice skating director stepped into the compressor room. Halfway down the stairs she hesitated, then exited the compressor room, and phoned 911 and the shopping mall security.

One of the health club workers made a separate phone call to the 911 emergency response unit, reporting that two people at the swimming pool in the mall were having trouble breathing. An emergency medical service (EMS) team and a fire engine unit responded to this call.

The firefighters and EMS team arrived at the scene at about 9:00 a.m. The slipperiness of the refrigerant oil which covered the compressor room floor and the clothing of the two injured workers made the rescue effort extremely difficult. Firefighters in full turnout gear and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) entered the compressor room, located maintenance worker #2, and removed him from the room.

Another firefighter wearing turnout gear and SCBA, and an emergency medical technician (EMT), who was not wearing any type of respiratory protection, entered the compressor room, and removed the maintenance supervisor. Immediately following the rescue effort, a bearded firefighter donned an SCBA and entered the compressor room. Because a face seal may not be achieved on a bearded face, this firefighter did not receive adequate respiratory protection. The victim was not in plain sight, having fallen behind some refrigerant equipment and piping, and being covered with the mist. The emergency response team did not see the victim, and were not immediately aware of his presence, so they discontinued search and recovery operations in the compressor room, and started resuscitation on the maintenance worker and supervisor.

Both workers were taken to the skate changing area where the rescuers started cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and also attempted to insert airway tubes. However, during the rescue effort, the compressor room doors had been propped open allowing the CFC-22 refrigerant to flow into the skate changing area and adjacent areas. The first responders inhaled CFC-22 vapor during the resuscitation efforts in sufficient quantities to cause symptoms of poor motor coordination, and difficulty in judgement. As a result, they were unable to continue resuscitation until other EMS personnel arrived and assisted in moving the two injured workers to the open air immediately outside the building. Here the injured workers received continued CPR, and ultimately were revived.

By about 9:20 a.m., a total of 3,200 pounds of CFC refrigerant had leaked out of the refrigeration system (685 pounds before 8:30 a.m., and 2,515 pounds between 8:30 a.m. and 9:20 a.m., as estimated by the local mechanical engineer).

The first responders were unaware that the victim was still inside the compressor room. However, the ice skating director insisted that there was yet a third person inside, and another firefighter entered the compressor room. He located the victim (at 9:22 a.m.), and removed him to the open air immediately outside the building. The victim received both CPR at the scene, and en route to a local hospital, where he was pronounced dead by the attending physician. The maintenance supervisor and maintenance worker were transported to a local hospital where they subsequently recovered.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The medical examiner listed the cause of death as asphyxiation by oxygen displacement with refrigerant (CFC-22).

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1: Employers should insure that workers are adequately protected from recognized hazards by installing appropriate engineering controls.

Discussion: Employers who operate refrigeration systems should ensure that workers are protected from harmful exposure to refrigerants. Appropriate engineering controls should be used when necessary to prevent harmful exposures. According to the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-conditioning Engineers, Inc. (ASHRAE) Standard (ANSI/ASHRAE 15-1989), the following control measures are required for this type of refrigeration system. None of these controls were in place before this incident occurred:

- “Emergency remote controls to stop the action of the refrigerant compressor shall be provided and located immediately outside the machinery room.” (paragraph 10.14.g). In this incident the shutoff switch to the compressor was located inside the compressor room.

- Machinery rooms “… shall have continuous ventilation or be equipped with a vapor detector that will automatically start the ventilation system and actuate an alarm at the lowest practical detection levels not exceeding the volume percent limits …” (or when CFC-22, or other Group I refrigerants cause the volume of oxygen to fall below 20%). “The vapor detector shall also initiate a supervised alarm so corrective action can be initiated. Periodic tests of the detector(s), alarm(s), and mechanical ventilating system shall be performed.” To provide adequate warning, sensors for vapor-activated alarms should be located in areas where refrigerant vapor from a leak is likely to concentrate. The alarm sensor should be located near the floor level for CFC-22 and other refrigerants heavier than air, (paragraphs 10.14.h, and 6.4.4.d).

- Mechanical ventilation “… shall be by one or more power- driven fans capable of exhausting air from the machinery room at least in the amount given in the formula in paragraph 10.13.6.2.” To provide adequate ventilation, the exhaust air intake should be located in an area where refrigerant vapor from a leak is likely to concentrate. The exhaust air intake should therefore be located near the floor level for CFC-22 and other refrigerants heavier than air, (paragraphs 10.13.3, and 10.13.4). In this incident the exhaust air intake was located approximately 8 feet above the compressor room floor.

- “Emergency remote controls for the mechanical means of ventilation shall be provided and located outside the machinery room.” (paragraph 10.14.i). In this incident the exhaust ventilation power switch was located inside the compressor room.

- Each refrigeration machinery room shall have tight-fitting doors (paragraph 10.13.2).

Recommendation #2: Employers should develop and implement a maintenance program that will address routine inspection and repair of refrigeration systems.

Discussion: Although CFC-22 is considered to have a low toxicity, in high concentrations it can displace the amount of oxygen necessary to support life. Since most refrigeration systems of this type contain CFC-22 under pressure, and have refrigeration system components enclosed inside a mechanical room or “compressor room,” the potential for an asphyxiating atmosphere is always present. It is, therefore, imperative that regularly scheduled maintenance inspections be conducted by qualified refrigeration specialists. Any refrigeration leak or other serious deficiency should be immediately documented and properly repaired by the qualified refrigeration specialists. If it cannot be repaired immediately, the refrigeration system should be shut down and secured until repairs can be completed.

Recommendation #3: Employers should develop and implement a safety program designed to help workers recognize, understand, and control hazards.

Discussion: Employers should evaluate the tasks performed by workers, identify potential hazards, develop and implement a safety program addressing these hazards, and provide worker training in safe work procedures. The safety program should include a written hazard communication program. OSHA Standard 29 CFR 1910.1200 (e)(1) states, “Employers shall develop, implement, and maintain a written hazard communication program …” This program should cover such issues as labels and other forms of warning, Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS), and employee safety information and training.

Recommendation #4: Employers should ensure that workers are adequately protected from recognized hazards with appropriate personal protective equipment.

Discussion: The employer should develop and implement a comprehensive respirator program as required by OSHA Standard 29 CFR 1910.134, including fit testing, and employee training in the use and limitations of different respirators. Circumstances in this incident indicate that the CFC-22 displaced the oxygen concentration in the compressor room to less than 19.5%, which created an atmosphere immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH). Although the victim and the maintenance supervisor wore an air-purifying respirator (organic vapor cartridge type), the respirator was dangerously inappropriate because the atmosphere was oxygen-deficient. Respirators should be selected according to criteria in the “NIOSH Respirator Decision Logic” (NIOSH Publication No. 87-108). Additional information on the characteristics and use of respirators is available in the “NIOSH Guide to Industrial Respiratory Protection” (NIOSH Publication No. 87-116).

Recommendation #5: Multiple-employer worksites should develop and implement comprehensive emergency action plans for each facility or complex.

Discussion: A written emergency action plan (in accordance with OSHA Standard 29 CFR 1910.38) at a minimum should include the following elements:

- Emergency escape procedures and emergency escape route assignments.

- Procedures to be followed by employees who remain to operate critical plant operations before they evacuate.

- Procedures to account for all employees after emergency evacuation has been completed.

- Rescue and medical duties for those trained employees who are to perform them.

- The preferred means of reporting emergencies.

- The names of persons who can be contacted for information or explanation of duties under the plan.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should establish a registry identifying potentially hazardous facilities, and inform emergency rescue personnel of these potential hazards, and of appropriate rescue methods and equipment.

Discussion: Fire departments and/or emergency rescue services should establish a registry of potentially hazardous facilities within the area they serve. Such a registry should provide not only the name of any potentially hazardous substance, but also sufficient information so that emergency response personnel can plan safe and appropriate rescues. Emergency rescue planning should be coordinated with other involved agencies so that combined rescue efforts are organized and effective.

Recommendation #7: Fire departments and/or emergency rescue services should ensure that responding personnel are properly trained in the selection and use of respiratory protective equipment.

Discussion: In this incident, an emergency medical technician (EMT) entered the oxygen-deficient mechanical room without wearing any respiratory protection. It should also be noted that immediately following the rescue effort, a bearded firefighter donned an SCBA and entered the compressor room (to assist setting up exhaust fans for purging the building). Since a face seal may not be achieved on a bearded face, this firefighter did not receive adequate respiratory protection. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1404 3-1.2 and 3-1.3 (Standard For a Fire Department Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus Program) state, “Respiratory protection shall be used by all personnel who are exposed to respiratory hazards or who may be exposed to such hazards without warning …” Respiratory protective equipment shall be used by all personnel operating in confined spaces, below ground level, or where the possibility of a contaminated or oxygen deficient atmosphere exists until or unless it can be established by monitoring and continuous sampling that the atmosphere is not contaminated or oxygen deficient.” Fire departments should develop and implement a respiratory protection program which includes training in the proper selection and use of respiratory protective equipment according to NIOSH Publications “Respirator Decision Logic” (Publication No. 87-108) and “Guide to Industrial Respiratory Protection” (Publication No. 87-116).

REFERENCES

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Request for Assistance in Preventing Death from Excessive Exposure to Chlorofluorocarbon 113 (CFC-113). Cincinnati, Ohio, May 1989. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 89-109, May 1989.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Request for Assistance in Preventing Occupational Fatalities in Confined Spaces. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 86-110, January 1986.

Schlager LM, Pate MB, Bergles AE. “Performance of Micro-fin Tubes with Refrigerant-22 and Oil Mixtures.” ASHRAE Journal. November 1989: 17-28.

Litchfield MH and Longstaff E: “The Toxicological Evaluation of Chlorofluorocarbon 22 (CFC 22): Summaries of Toxicological Data.” Fd Chem Toxic 22: 465-475.

“Chlorodifluoromethane.” IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans: Some Halogenated Hydrocarbons and Pesticide Exposures. (Vol. 41), Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1986, 237-252.

“Monochlorodifluoromethane,” CHEMTREC. Phone (800) 424-9300, October 1984: 487-491.

“Chlorodifluoromethane.” Proctor NH, Hughes JP, Fischman ML, (eds). Chemical Hazards of the Workplace.” Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1988, 135-136.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Working in Confined Spaces, Cincinnati, Ohio: December 1979. DHEW (NIOSH) Publication No. 80-106.

Industrial Exposure and Control Technologies for OSHA Regulated Hazardous Substances, U.S. Dept. of Labor, March 1989, Vol. I, pp. 440-442.10.

OSHA Standards 29 CFR 1910.1200 (e)(1), 29 CFR 1910.134, 29 CFR 1910.38, July 1990.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Cincinnati, Ohio: May, 1987. Respirator Decision Logic, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 87-108.

NIOSH Guide to Industrial Respiratory Protection, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 87-116, September, 1987.

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc. (ASHRAE) Standard Safety Code for Mechanical Refrigeration (ANSI/ASHRAE 15-1989), 1989.

Figure.

<