Laborer Fatally Injured While Cleaning Concrete Mixer - Tennessee

NIOSH In-house FACE Report 95-12

Summary

On May 15, 1995, a 25-year-old male laborer (the victim) at a concrete-pipe-manufacturing facility died from injuries he received while cleaning a ribbon-type concrete mixer. The mixer is cleaned out each day at the end of the shift, by the laborer and the mixer operator. The procedure for cleaning the mixer is to shut off the power at the breaker box (approximately 35 feet from the mixer), push the toggle switch (adjacent to the mixer) for the mixer to determine if the power is off, and then enter the mixer to scrape down the inside and shovel the concrete debris out the front discharge chute. The event was un-witnessed; however, it is assumed that the mixer operator shut off the main breaker, and, instead of the normal procedure for checking the mixer before entry, decided to make a telephone call. The victim, a Mexican immigrant who spoke or read very little English, not knowing the mixer had been de-energized at the main breaker, turned the mixer back on, thinking he had shut it off. The victim then entered the mixer without first pushing the toggle switch to verify that the power was off and started cleaning. The mixer operator returned from making his telephone call, and pushed the toggle switch to check the mixer, and heard the victim scream. He proceeded immediately to the main breaker and shut off the mixer. The emergency medical services was called, arrived at the site in 30 minutes, and transported the victim to a local hospital, where he was then transferred to a local trauma center. He died at the trauma center approximately 4 hours later. NIOSH investigators concluded that, in order to prevent similar incidents, employers should:

- conduct a safety hazard analysis of all work locations in all plants, and implement corrective action where necessary

- develop, implement, and enforce a written safety program which includes task specific training and lockout/tagout procedures.

Introduction

On May 15, 1995, a 25-year-old male laborer (the victim) died as a result of a ribbon-type concrete mixer being turned on while he was inside cleaning the mixer. On May 23, 1995, officials of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the State of Tennessee (TOSHA) notified the Division of Safety Research (DSR) of this fatality, and requested technical assistance. On July 11, 1995, a DSR environmental health and safety specialist conducted an on-site investigation, accompanied by the TOSHA investigator. The incident was reviewed with the TOSHA investigator, and employer representatives. Photographs were taken of the incident site during the investigation.

The employer was a concrete-pipe-manufacturing facility that produced concrete sewer pipes of various sizes. The facility operated on one 8-hour production shift (7:00 am -3:30 p.m.) five days a week, employing 12 workers performing various tasks in the production of concrete sewer pipe. The company had 6 operating plants throughout the state, employing a total of 85 workers. The facility’s safety department was comprised of an administrative manager, the plant manager, and a supervisor, all with collateral safety duties. The employer had hand-written safety procedures that included lock-out/tag-out procedures; however, the employer did not provide any formal task training to employees. Employees received on-the-job orientation training. The victim had worked for the employer for 11 months.

Back to Top

Investigation

On the day of the incident, workers at the facility were manufacturing concrete sewer pipe. The workers at the facility began the work shift at 7 a.m., and ended production activities around 2:30 p.m., to perform clean-up operations, prior to quitting at 3:30 p.m. The process for manufacturing the concrete pipe starts with pre-measured/weighed cement, sand, and gravel being dumped into a “lolly” hopper; the hopper then travels via rail approximately 15 feet and dumps the cement, sand and gravel mixture into a ribbon-type concrete mixer (Figure 1). The 2-cubic-yard mixer is belt-driven by a 50 horsepower motor, is approximately 7 feet in length by 4 feet in diameter, and has two mixing blades. Water is added to the mixture during the 3- to 4-minute mixing cycle. The mixed concrete is dumped from the mixer through a front chute opening into a skip-hoist hopper, which is then hoisted up approximately 30 feet, and dumped into a surge hopper. From the surge hopper the concrete flows into a pipe mold which contains wire reinforcement and is located on a turntable. The round turntable holds two pipe molds, one empty, and one being filled. As soon as one mold is filled with concrete, the turntable rotates 180 degrees, the filled mold is removed by a fork lift and placed in the curing bay (approximately 30 feet from the turntable). The fork lift returns from the curing bay with an empty mold (with wire reinforcing inside), and places it on the turntable.

|

|

Figure 1. A ribbon-type concrete mixer.

|

The responsibilities of the victim consisted of spot welding the wire reinforcing used for the concrete pipe, and general clean-up duties. On the day of the incident, at approximately 2:30 p.m., the mixer operator shut off the toggle switch operating control (Figure 2) to the concrete mixer, walked approximately 35 feet to the 440 volt breaker for the mixer (Figure 3), and shut it off. The normal procedure was to return to the mixer after turning off the main breaker to determine if it had been de-energized, by pushing the toggle switch that controlled the mixer. However, on this day, the mixer operator went to make a telephone call. During his absence, the victim, unaware that the mixer operator had already shut off the main breaker, went over to the breaker box and thinking he had shut off the breaker, turned it on. The victim then proceeded to the mixer room, and without depressing the toggle switch to determine if the power was off, entered the mixer and started the cleaning procedure. The mixer operator returned and depressed the toggle switch to the mixer to verify the power was off. Hearing the victim scream, the mixer operator went immediately to the main breaker and shut it off. The emergency medical services was called and arrived in 30 minutes. The victim was removed from the mixer and transported to a local hospital, where he was then transferred to a local trauma center. The victim died approximately 4 hours later at the trauma center.

|

|

Figure 2. The toggle switch operating control.

|

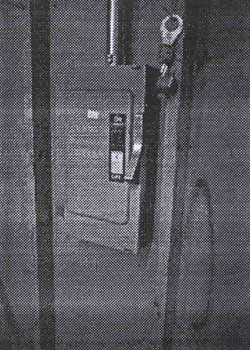

Figure 3 shows the new 440 breaker box that was installed after the fatal incident. The new 440 volt breaker box was installed in the mixer room, and is similar to the old breaker box which was located approximately 35 feet from the mixer room, except the old box did not have a safety lock-out as shown in this figure.

|

|

Figure 3. The new 440 breaker box that was installed after the fatal incident.

|

During this fatality investigation, it was noted and brought to the attention of the employer that the operation of the forklift (from the molding operation to the curing bay, and back again) appeared to be a hazardous operation. Because the forklift operator is on a tight production schedule, he cannot lose much time. Therefore, someone walking in the path of the forklift is at risk of injury. There is a flashing light on the forklift (no alarm -which probably could not be heard because of the ambient production noise); however, there are blind spots in which the operator could not see a worker in time to stop. It was recommended this area be marked as “off limits” to workers, to prevent a possible serious injury.

Back to Top

Cause of Death

The medical examiner listed the cause of death as crushing lower trunk injuries.

Back to Top

Recommendations/Discussion

Recommendation #1: Employers should conduct a safety hazard analysis of all work locations in all plants, and imp1ement corrective action where necessary.

Discussion: Many work locations present safety hazards that could cause injury to the worker. Each work location in each plant should be evaluated for the possibility of: electrical hazards, chemical hazards, release of hazardous energy (e.g., moving parts of machinery), fire or explosion hazards, moving equipment (e.g., forklifts, man lifts, etc.), excessive noise, heat stress, ergonomic problems (e.g., comfort of workers operating machines requiring a repeated task), falls from elevations or falls over equipment or objects on the floor, flying objects (e.g., eyes not being protected), or a combination of hazards. Once potential hazards are identified, corrective action should be implemented as necessary to reduce to risk of injury.

Recommendation #2: Employers should develop, implement and enforce a written safety program which includes task-specific training and lockout/ragout procedures.

Discussion: Although the employer has a limited, hand-written safety program, which includes lockout for electrical maintenance, the safety program should be formalized throughout the entire company. Written safety programs should be developed that describe safe work procedures for all tasks to be conducted, and include discussions of appropriate tools (e.g., safety lockout of equipment), and protective equipment required. Additionally, training should be provided to all workers to ensure they are aware of the safe work procedures, and the safety hazards involved with each task. If the workers do not speak English, then the instructions, written and oral, should be in the language that is understood by the worker(s) .In this incident, the victim did not speak English and understood very little spoken or written English; also, it appears he was not aware of the purpose of locking out equipment. (Note: it was reported by the safety officer of the company, that at one time a lockout procedure was in place; however, no one knows when or why it was discontinued.) Currently, OSHA standard 29 CFR 1910.147 requires the control of hazardous energy through the use of lockout/tagout. If the workers are exposed to the release of hazardous energy, then the energy should be locked out to prevent inadvertent activation of the equipment. A comprehensive lockout/tagout program should include procedures for:

- de-energization of potentially hazardous energy (electrical, chemical, mechanical, etc.);

- locking and tagging of the energy control source;

- dissipating or blocking of any stored energy, e.g., energy stored in fly wheels, springs, etc; and

- verification that the hazardous energy has been controlled.

The program should also include procedures for the safe re-energization of equipment once maintenance or cleaning has been completed. Employers should also ensure that all energy control equipment, e.g., breaker panels, have the capability to be locked out.

Back to Top

References

- Code of Federal Regulations, 29 CFR 1910.147 (1993) .The control of hazardous energy (lockout/tagout) .U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Ashford, N.A., Crisis in the Workplace: Occupational Disease and Injury, A report to the Ford Foundation, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 589 pages, 1979.