Hospital Costs and Resource Use for Children and Adolescents with Congenital Heart Defects

CDC researchers found that in 2009, hospitalized U.S. children and adolescents who had a congenital heart defect (CHD) had more expensive hospital stays than those who were hospitalized without a CHD. The most expensive hospital stays were for infants, children, and adolescents with critical congenital heart defects (CCHD). This information might help improve public health practices and healthcare planning to adequately serve people of all ages with a CHD. You can read the abstract of the article here.

Main Findings from this Study

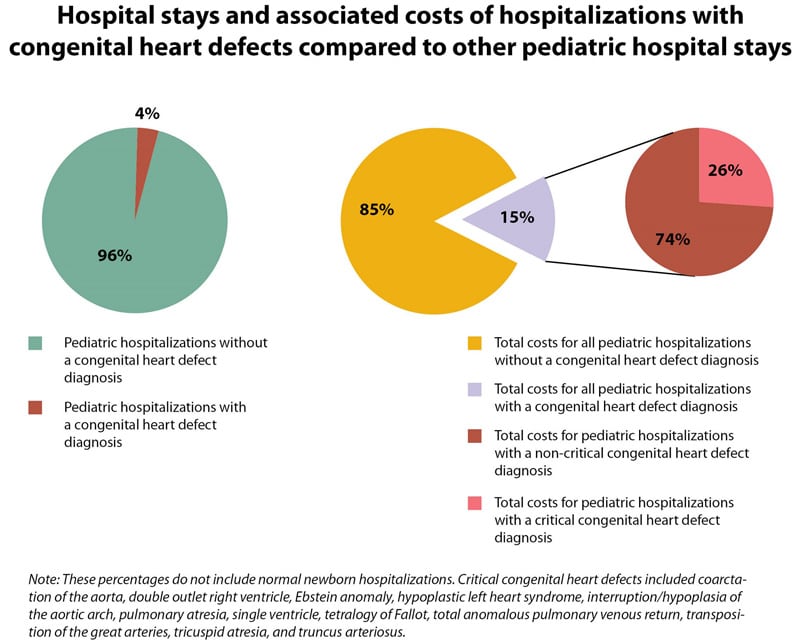

- Hospitalizations of patients with a CHD made up 3.7% of all hospitalizations in the United States for children and adolescents aged 0-20 years.

- Hospital costs for patients with a CHD exceeded $5.6 billion in 2009. Although patients with a CHD comprised only 3.7% of the hospitalizations, the costs were 15.1% of the total costs for all U.S. hospitalizations for children and adolescents aged 0-20 years.

- 26.7% of the costs for children and adolescents with a CHD were from hospitalizations of patients with a CCHD diagnosis.

- Hospital costs were highest if:

- The patient was less than a year old;

- The patient had a CCHD (as compared to other types of CHDs);

- The patient died while in the hospital.

- Hospital costs were highest for patients with these CCHDs: hypoplastic left heart syndrome, coarctation of the aorta, and tetralogy of Fallot.

- Although babies less than one year old with a CHD had the highest costs, the costs of hospitalizations due to a CHD were still very high across all ages: the average cost per hospitalization among patients 1-20 years old was $25,000.

About this Study

- CHDs are the most common type of birth defect, affecting nearly 1% of all babies born in the United States1.

- About 1 in 4 of these babies have a type of CHD called a critical congenital heart defect (CCHD)2, 3.

- Improvements in detection and treatment have allowed many babies born with a CHD to live longer lives and many are expected to live well into adulthood4-6.

- Although improvements in detection and treatment have allowed many babies born with a CHD to live longer lives4-6, little is known about the healthcare needs of children and adolescents with CHDs or the impact of this population on hospital resource use and the resulting costs that the hospitals experience.

- The researchers that conducted this study used the 2009 Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID), which is maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)7, 8. Data from forty-four states were included in this analysis, which gives us a better picture of hospital resource use across all of the United States.

- The researchers included hospital discharges (medical records completed after a hospital stay) that occurred between January 1 and December 31, 2009, of patients up to 20 years old when they came to the hospital.

- All of these patients were diagnosed with at least one CHD. Researchers grouped the patients into those with a CCHD, and those with a non-critical CHD.

- The patients were also grouped by age (less than a year old, 1-10 years old, and 11-20 years old).

- The researchers compared the average hospital costs for patients with a CHD and patients without a CHD (not including normal newborns who were simply born in the hospital). They further compared hospital costs for patients with a CCHD and patients with a non-critical CHD. Hospital costs are different than what a health insurance company or person sees on a bill. Hospital costs are how much it costs the hospital to provide services (for example – how much it costs to pay staff, run tests, give medicine, or perform surgery).

Heart Defects: CDC’s Activities

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) works to identify causes of CHDs and ways to prevent them. We do this through:

- Surveillance and Disease Tracking:

- CDC funds and coordinates the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program (MACDP). CDC also funds population-based state tracking programs. Birth defects tracking systems are vital to help us find out where and when birth defects occur and whom they affect.

- CDC funds projects to track CHDs across the lifespan in order to learn about health issues and needs among all age groups.

- CDC, in partnership with March of Dimes, surveyed adults with CHDs to assess their health, social and educational status, and quality of life. The survey is called CH STRONG, Congenital Heart Survey To Recognize Outcomes, Needs, and well-beinG.

- Research: CDC funds the Centers for Birth Defects Research and Prevention, which collaborate on large studies such as the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS) (births 1997-2011) and the Birth Defects Study To Evaluate Pregnancy exposureS (BD-STEPS) (began with births in 2014). These studies are working to identify factors that put babies at risk for birth defects, including heart defects.

- Collaboration:

- CDC is assessing states’ needs for help with CCHD screening and reporting of screening results. CDC helps states and hospitals better understand the cost and impact of CCHD screening. CDC also promotes collaboration between birth defects tracking programs and newborn screening programs to improve understanding of the effectiveness of CCHD screening.

- CDC provides technical assistance to the Congenital Heart Public Health Consortium (CHPHC). The CHPHC is a group of organizations uniting resources and efforts in public health activities to prevent congenital heart defects and improve outcomes for affected children and adults. Their website provides resources for families and providers on CHDs.

More Information

To learn more about congenital heart defects, please visit https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/.

Reference for Key Findings

Simeone RM, Oster ME, Cassell CH, Armour BS, Gray DT, Honein MA. Pediatric inpatient hospital resource use for congenital heart defects. Birth Defects Research Part A: 2014; 100(12): 934-943.

References

- Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, Correa A. Prevalence of congenital heart defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998-2005. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;153:807-13.

- Botto LD, Correa A, Erickson JD. Racial and temporal variations in the prevalence of heart defects. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E32.

- Mahle WT, Newburger JW, Matherne GP, Smith FC, Hoke TR, Koppel R, Gidding SS, Beekman RH 3rd, Grosse SD. Role of pulse oximetry in examining newborns for congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the AHA and APA. Circulation. 2009;120:447-58.

- Oster M, Lee KA, Honein MA, Colorusso T, Shin M, Correa A. Temporal trends in survival among infants with critical congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1502-e8.

- Williams RG, Pearson GD, Barst RJ, Child JS, del Nido P, Gersony WM, Kuehl KS, Landzberg MJ, Myerson M, Neish SR, Sahn DJ, Verstappen A, Warnes CA, Webb CL. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on research in adult congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:701-7.

- Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, Rahme E, Pilote L. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation. 2007;115:163-72.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2009. Available at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp. Accessed March 8, 2014.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Introduction to the HCUP KIDS’ Inpatient Database (KID) 2009. 2011. Available at http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/kid/KID_2009_Introduction.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2014.