Facts about Craniosynostosis

Craniosynostosis is a birth defect in which the bones in a baby’s skull join together too early. This happens before the baby’s brain is fully formed. As the baby’s brain grows, the skull can become more misshapen.

What is Craniosynostosis?

Craniosynostosis is a birth defect in which the bones in a baby’s skull join together too early. This happens before the baby’s brain is fully formed. As the baby’s brain grows, the skull can become more misshapen. The spaces between a typical baby’s skull bones are filled with flexible material and called sutures. These sutures allow the skull to grow as the baby’s brain grows. Around two years of age, a child’s skull bones begin to join together because the sutures become bone. When this occurs, the suture is said to “close.” In a baby with craniosynostosis, one or more of the sutures closes too early. This can limit or slow the growth of the baby’s brain.

When a suture closes and the skull bones join together too soon, the baby’s head will stop growing in only that part of the skull. In the other parts of the skull where the sutures have not joined together, the baby’s head will continue to grow. When that happens, the skull will have an abnormal shape, although the brain inside the skull has grown to its usual size. Sometimes, though, more than one suture closes too early. In these instances, the brain might not have enough room to grow to its usual size. This can lead to a build-up of pressure inside the skull.

Types of Craniosynostosis

The types of craniosynostosis depend on what sutures join together early.

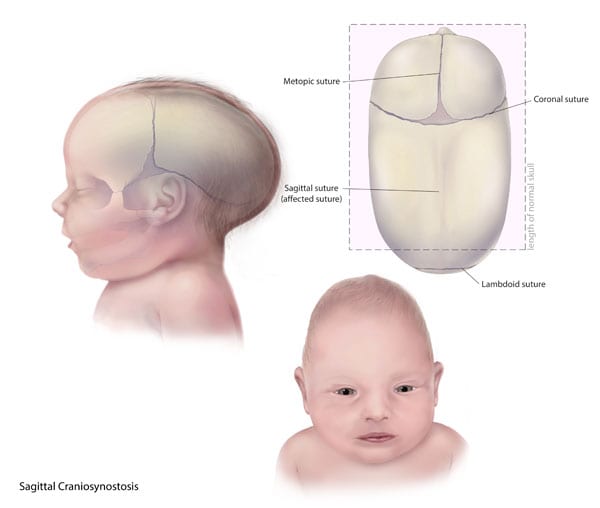

- Sagittal synostosis– The sagittal suture runs along the top of the head, from the baby’s soft spot near the front of the head to the back of the head. When this suture closes too early, the baby’s head will grow long and narrow (scaphocephaly). It is the most common type of craniosynostosis.

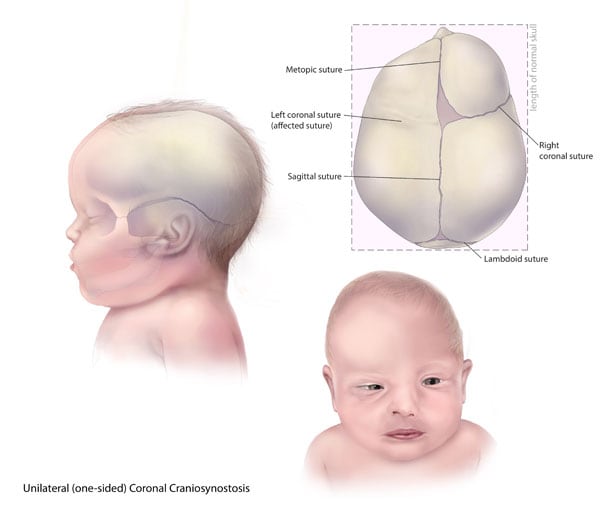

- Coronal synostosis – The right and left coronal sutures run from each ear to the sagittal suture at the top of the head. When one of these sutures closes too early, the baby may have a flattened forehead on the side of the skull that closed early (anterior plagiocephaly). The baby’s eye socket on that side might also be raised up and his or her nose could be pulled toward that side. This is the second most common type of craniosynostosis.

- Bicoronal synostosis – This type of craniosynostosis occurs when the coronal sutures on both sides of the baby’s head close too early. In this case, the baby’s head will grow broad and short (brachycephaly).

- Lambdoid synostosis – The lambdoid suture runs along the backside of the head. If this suture closes too early, the baby’s head may be flattened on the back side (posterior plagiocephaly). This is one of the rarest types of craniosynostosis.

- Metopic synostosis – The metopic suture runs from the baby’s nose to the sagittal suture at the top of the head. If this suture closes too early, the top of the baby’s head shape may look triangular, meaning narrow in the front and broad in the back (trigonocephaly). This is one of the rarest types of craniosynostosis.

Other Problems

Many of the problems a baby can have depend on:

- Which sutures closed early

- When the sutures closed (was it before or after birth and at what age)

- Whether or not the brain has room to grow

Sometimes, if the condition is not treated, the build-up of pressure in the baby’s skull can lead to problems, such as blindness, seizures, or brain damage.

How Many Babies are Born with Craniosynostosis?

Researchers estimate that about 1 in every 2,500 babies is born with craniosynostosis in the United States.1

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of craniosynostosis in most infants are unknown. Some babies have a craniosynostosis because of changes in their genes. In some cases, craniosynostosis occurs because of an abnormality in a single gene, which can cause a genetic syndrome. However, in most cases, craniosynostosis is thought to be caused by a combination of genes and other factors, such as things the mother comes in contact with in her environment, or what the mother eats or drinks, or certain medications she uses during pregnancy.

CDC, like the many families of children with birth defects, wants to find out what causes these conditions. Understanding the factors that are more common among babies with a birth defect will help us learn more about the causes. CDC funds the Centers for Birth Defects Research and Prevention, which collaborate on large studies such as the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS; births 1997-2011), to understand the causes of and risks for birth defects, such as craniosynostosis.

Recently, CDC reported on important findings from research studies about some factors that increase the chance of having a baby with craniosynostosis:

- Maternal thyroid disease ― Women with thyroid disease or who are treated for thyroid disease while they are pregnant have a higher chance of having an infant with craniosynostosis, compared to women who don’t have thyroid disease.2

- Certain medications ― Women who report using clomiphene citrate (a fertility medication) just before or early in pregnancy are more likely to have a baby with craniosynostosis, compared to women who didn’t take this medicine.3

CDC continues to study birth defects, such as craniosynostosis, and how to prevent them. If you are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant, talk with your doctor about ways to increase your chances of having a healthy baby.

Diagnosis

Craniosynostosis usually is diagnosed soon after a baby is born. Sometimes, it is diagnosed later in life.

Usually, the first sign of craniosynostosis is an abnormally shaped skull. Other signs may include:

- No “soft spot” on the baby’s skull

- A raised firm edge where the sutures closed early

- Slow growth or no growth in the baby’s head size over time

Doctors can identify craniosynostosis during a physical exam. A doctor will feel the baby’s head for hard edges along the sutures and unusual soft spots. The doctor also will look for any problems with the shape of the baby’s face. If he or she suspects the baby might have craniosynostosis, the doctor usually requests one or more tests to help confirm the diagnosis. For example, a special x-ray test, such as a CT or CAT scan, can show the details of the skull and brain, whether certain sutures are closed, and how the brain is growing.

Treatments

Many types of craniosynostosis require surgery. The surgical procedure is meant to relieve pressure on the brain, correct the craniosynostosis, and allow the brain to grow properly. When needed, a surgical procedure is usually performed during the first year of life. But, the timing of surgery depends on which sutures are closed and whether the baby has one of the genetic syndromes that can cause craniosynostosis.

Babies with very mild craniosynostosis might not need surgery. As the baby gets older and grows hair, the shape of the skull can become less noticeable. Sometimes, special medical helmets can be used to help mold the baby’s skull into a more regular shape.

Each baby born with craniosynostosis is different, and the condition can range from mild to severe. Most babies with craniosynostosis are otherwise healthy. Some children, however, have developmental delays or intellectual disabilities, because either the craniosynostosis has kept the baby’s brain from growing and working normally, or because the baby has a genetic syndrome that caused both craniosynostosis and problems with how the brain works. A baby with craniosynostosis will need to see a healthcare provider regularly to make sure that the brain and skull are developing properly. Babies with craniosynostosis can often benefit from early intervention services to help with any developmental delays or intellectual problems. Some children with craniosynostosis may have issues with self-esteem if they are concerned with visible differences between themselves and other children. Parent-to-parent support groups also can be useful for new families of babies with birth defects of the head and face, including craniosynostosis.

Other Resources

The views of these organizations are their own and do not reflect the official position of CDC.

- Children’s Craniofacial Association (CCA)

CCA addresses the medical, financial, psychosocial, emotional, and educational concerns relating to craniofacial conditions. - The National Craniofacial Association (FACES)

FACES is dedicated to assisting children and adults who have craniofacial disorders resulting from disease, accident, or birth.

References

- Boulet SL, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA. A population-based study of craniosynostosis in metropolitan Atlanta, 1989-2003. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2008;146A:984–991.

- Rasmussen SA, Yazdy MM, Carmichael SL, Jamieson DJ, Canfield MA, Honein MA. Maternal thyroid disease as a risk factor for craniosynostosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:369-377.

- Reefhuis J, Honein MA, Schieve LA, Rasmussen SA, and the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of clomiphene citrate and birth defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2005. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:451–457.